In the second part, Nachiketa elaborates on the evolution of erotic sculpture, anthropological inclination, and Tantric influence. An exclusive for Different Truths.

Scholars had the opinion that erotic sculpture evolved during the medieval period under influence of Tantrism, guided by esoteric cults, practiced as the Kaulas and Kapalkas. To attain religious merit erotic ritual of Maithuna was practiced by a selective civil citizen in secrecy. A special cult of the Sun as the universal fructifying force was intermingled with the rites. The woman is the altar as well as Brahman for Tantrikas and Saktas in their worship manual. The Goddess incarnates herself. Every female is a room of Goddess. The Goddess incarnates in women. women are sacred and sanctified. Tantric Mahacina-kramachara says, “Women are the Gods, life, and adornment, so respect women.”

Elgood (2000) has the view of anthropological inclination relating to Tantric philosophy. Scholars have decoded Tantric decorum…

Elgood (2000) has the view of anthropological inclination relating to Tantric philosophy.

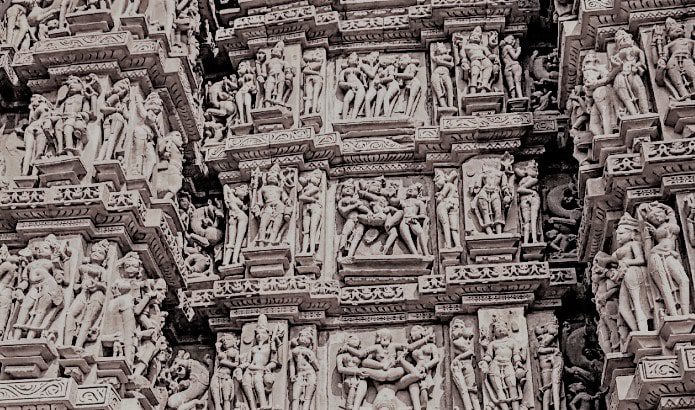

Scholars have decoded Tantric decorum (intentional language) to read the expression of deeper and abstract philosophical ideas on the desirous play and the influence of ideas of tantrism on the pleasure-loving aristocrats. The primitive pre-Aryan cults and practices with the ancient association of the magico-protective function of sexuality prevailed. The concept of stimulation of the generative powers expressed in the king/concubine relationship evidenced by the imagery on the Lakshmana Temple at Khajuraho. The imagery of king, soldiers, and bestiality are there, might be as orgiastic sex as a commentary on certain tantric sex.

Desai cited by Elgood (2000), suggests the contexts in her authoritative work – (a) a result of a pervasive influence of Tantrism on Hinduism, (b) influence was reinforced by the association of Tantricks with pleasure-loving aristocrat, (c) deviation of courtly society from ascetic ideas, (d) entry of permissive group in society as evidenced by Kamasutra, (e) hidden meaning may also be used to camouflage message to the initiated or more intelligent, (f) the sexual pose carved on stone, according to the tantric Silpasastra, for the enjoyment of people from whom the symbolism of the yantra was hidden, and (f) supported Kramrisch’s claim that maithuna image echoed the Upanishadik text, which used the metaphor of the loving embrace of man and women to symbolise union or moksha.

Heather Elgood (2000) opined that post 900-1400 AD, a region of India interpreted erotic motifs according to regional belief as evidenced in Orissan, Chandella sculpture…

Heather Elgood (2000) opined that post 900-1400 AD, a region of India interpreted erotic motifs according to regional belief as evidenced in Orissan, Chandella sculpture, which had a frank approach. Whereas Gujrat and Maharashtra remain submissive, South India adopted un auspiciousness. She did not agree with Desai and concluded: The wave of Maithuna image propagated and established in the tenth to eleventh centuries, resulting out of the different factors. Continuity of primitive magico-protective beliefs and customs remained in force; second, Tantrism’s impact on the aristocratic pleasure-loving court; third, the use of punning and double meaning through the frieze narrative and sophisticated dramatic art; fourth the nexus of obscenities, courtesans, and maithuna couples for their generative potential in order to keep the tradition of ancient ideas of magico-protective ritual; fifth, Yantra which expressed the deep universal meaning of union as hidden agenda and sixth, Shilpa cannons suggests that the purpose of the erotic image was to give delight. Finally, the expression of union depicts the Sandhyavasa of yogic forms on the union of two breaths, Prana and Aprana.

She further concluded, “…to understand the significance and meaning of the Maithuna images requires an openness to double meaning and an acceptance of the juxtaposition of the obscene and the sublime from a western audience. One must dissociate sin from sexuality and see rather than BHOGA – enjoyment-is a form of yoga-union. One must experience a timelessness, a place which is silent and clear, an inner world, still yet vibrating with pulse, heat intensity and the light of the inner union of energies.”

The tantric cult is glorified metaphysics with the mixture of the grossest forms of physical and sensual indulgence.

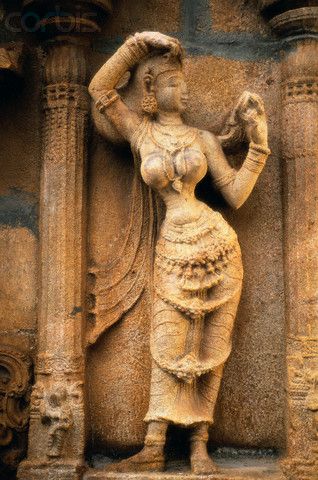

Tantric cult is glorified metaphysics with the mixture of the grossest forms of physical and sensual indulgence. Male God and Apsaras, Viṣṇu in erotic mode with women nearby Pūrṇakuṃbhas. Woman seated like Lajjā-Gaurī or Yoninilayā are some tantric symbol following rituals or Jogini cult of Khajuraho or Hirapur.

Buddhist View

Rishika Assomull (2013) concluded in her theses that the sense of nurture, love, sumptuousness, and wealth derived from the female form and her attributes battle with a deep, underlying fear of the feminine. During Mahayana tradition in nascent stage opened its doors to women in monasticism, women were addressed as a hindrance to personal salvation and enlightenment. On the contrary, defined as responsible for the perpetuation of samsara and were, therefore, the cause of all suffering.

Indian Yakshi, the female beauty, was designed to lure men to their doom and local disease’s demi-Goddesses.

Indian Yakshi, the female beauty, was designed to lure men to their doom and local disease’s demi-Goddesses. The Hindu legends speak about the fear of the female, expressed the notion of woman as the threat of the unclean. Female Yaksis represented those bipolar women empowered to progeny continuation and to protect from the disease and child mortality.

Risika inked, “Despite stylistic and iconographic influences from the Western world that depicted women as desirable, the idea of a good and evil mother that was emphasized in Brahmanical and Buddhist orthodoxy haunted the region. Spanning reflections from Rome, India, and Iran, the image of the woman conjures up notions of fruitfulness, maternity and abundance, but also a sense of seduction and accompanying it, the power that threatens all men. Though treated with honour and esteem, the permeating apprehension towards them signals worship that serves to mollify and appease the demonic woman. The discrete, ambivalent attitudes towards the female form and the woman in the milieu of society sometimes encompassed and at other times renounced in the multicultural setting of Gandhara. The alliances of the divine mirror the allocation of power, the inner workings of human interactions in society and the dynamics of the relationship between the individual and his object of worship.”

(To be continued)

Visuals by the internet

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By