The letter written on behalf of the Pension Parishad, a network of 100 civil society organisations in it, is in response to recent reports indicating that the Centre was considering a potential increase in pension. The activists believe that ‘piecemeal approaches to increasing pension amounts will not address the problem’, reviews Navodita, our Associate Editor, in the weekly column, exclusively for Different Truths.

Since the Union Budget day is coming closer, here’s what Arun Jaitley could possibly include more of – a right to live with dignity to the elders in their advanced years. Recently, a few social activists including Aruna Roy wrote to PM Narendra Modi urging him to ensure that the amount paid to a senior citizen as ‘pension’ should be no less than 50 percent of the notified minimum wage.

The letter written on behalf of the Pension Parishad, a network of 100 civil society organisations in it, is in response to recent reports indicating that the Centre was considering a potential increase in pension. The activists believe that ‘piecemeal approaches to increasing pension amounts will not address the problem’. What is required is a systematic protection and for good ‘social security measure’ for the elderly including timely payments, social audits, etc.

The letter written on behalf of the Pension Parishad, a network of 100 civil society organisations in it, is in response to recent reports indicating that the Centre was considering a potential increase in pension. The activists believe that ‘piecemeal approaches to increasing pension amounts will not address the problem’. What is required is a systematic protection and for good ‘social security measure’ for the elderly including timely payments, social audits, etc.

The government in 2015 had launched the Atal Pension Yojana for unorganised sector workers and was a replacement to previous government’s Swavalamban Yojana NPS Lite, which was not very successful. As a part of his ‘Sabka Sath Sabka Vikas’ drive, the PM had also launched the Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Beema Yojana and both these schemes were to be linked to the bank accounts opened under Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana. However, the big question is: are these implemented well? What is the feasibility of such pension schemes in India, let us examine it a bit.

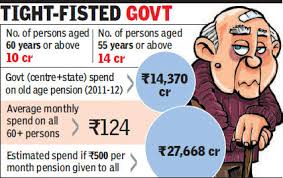

India has low pension coverage, and the current pension system is unable to fulfill its purpose. A non- contributory, basic pension can guarantee a regular income in old age to all residents of the country, regardless of earning or occupation. Developed countries are characterised mainly by highly organised formal labour markets and have systems of providing pensions to all those who contribute (through social security taxes) during their working years. On the contrary, developing countries are characterised mostly by informal labour markets, which force respective governments to provide pensions on a discretionary basis. It reduces the overall coverage of pension in such countries, and India is no exception. In reality, there is a need for a good universal pension for the elderly.

contributory, basic pension can guarantee a regular income in old age to all residents of the country, regardless of earning or occupation. Developed countries are characterised mainly by highly organised formal labour markets and have systems of providing pensions to all those who contribute (through social security taxes) during their working years. On the contrary, developing countries are characterised mostly by informal labour markets, which force respective governments to provide pensions on a discretionary basis. It reduces the overall coverage of pension in such countries, and India is no exception. In reality, there is a need for a good universal pension for the elderly.

Pension serves various objectives – poverty release, consumption smoothing and insurance in respect of the aging population. Social security also helps in assuring the young that in old age there would be national savings to take care of any difficulties, implying that over-accumulation is not necessary during the younger days. In India, the tradition of dependence on children during old age is undergoing change because of socio-structural transformations. The elderly are facing different insecurities with respect to health – financial, physical and mental – thus demanding attention from policymakers, government authorities and voluntary organisations.

It is argued by several authors and thinkers that health problems, including medical care, is a primary  concern among the large majority of aged people as they become more and more susceptible to chronic diseases, physical disability, and mental incapacity. Inadequate access to health insurance is also a reality for a majority of the elderly. A great anxiety of old age relates to economic insecurity, especially among the elderly poor. In India, over 50% of the elderly lack financial insecurity and are ‘fully dependent on others’ for their economic needs. Moreover, according to a National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) report, complete economic dependence is higher for women than men and those, who are partially dependent on others are 50%.

concern among the large majority of aged people as they become more and more susceptible to chronic diseases, physical disability, and mental incapacity. Inadequate access to health insurance is also a reality for a majority of the elderly. A great anxiety of old age relates to economic insecurity, especially among the elderly poor. In India, over 50% of the elderly lack financial insecurity and are ‘fully dependent on others’ for their economic needs. Moreover, according to a National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) report, complete economic dependence is higher for women than men and those, who are partially dependent on others are 50%.

A universal pension scheme could be a good solution but as it is easy to monitor and also has very low administrative costs in comparison to other schemes. The Netherlands and Norway provide universal basic pensions to their citizens that are tax-financed. Similarly, South Africa, Australia, Brazil, Lesotho, and Chile also have pension schemes that exclude only a few. A basic universal pension based on the criteria of citizenship, residence, and age is provided by New Zealand, Mauritius, Botswana, Namibia, Bolivia, Nepal, Samoa, Brunei, Kosovo and Mexico City. Ironically only New Zealand out of these is a developed country. Even though it is criticised for high fiscal costs, empirical evidence shows otherwise. Kanchan Bharti, Ayanendu Sanyal, and Charan Singh in their article ‘Ageing in India’ believe that the burden of the universal pension scheme is nominal even if the economy is estimated to grow at a conservative rate of 6% or less.

Ageing has an impact on economic growth, savings, investment, consumption, labour market, public  finance –taxation, pension – intergenerational transfers, healthcare expenditure and financial markets. The fiscal impact of aging is substantial and therefore, in India, measures should be taken sooner than later to address this problem. The demographic dividend that the country enjoys would diminish by 2050. Since a large part of the population is unable to save for retirement due to either economic reasons or job instability, the onus lies on the government. There is a definitely a need to reorient their existing policies and schemes.

finance –taxation, pension – intergenerational transfers, healthcare expenditure and financial markets. The fiscal impact of aging is substantial and therefore, in India, measures should be taken sooner than later to address this problem. The demographic dividend that the country enjoys would diminish by 2050. Since a large part of the population is unable to save for retirement due to either economic reasons or job instability, the onus lies on the government. There is a definitely a need to reorient their existing policies and schemes.

Amidst other changes that the Finance Minister may bring about, due consideration should be made to the old age pension and its universalisation among all classes of the country.

©Navodita Pande

Photos from the Internet

#FiannceMinister #EconomyOfIndia #Pension #PensionParishad #UnionBudget #NationalSampleSurveyOrganisation #Aamonomics #DifferentTurhs

By

By

By

By

By

By