Dr Parneet chronicles the influence of the Bhagavad Gita on the West. She tells us how it influenced many English poets. An exclusive for Different Truths.

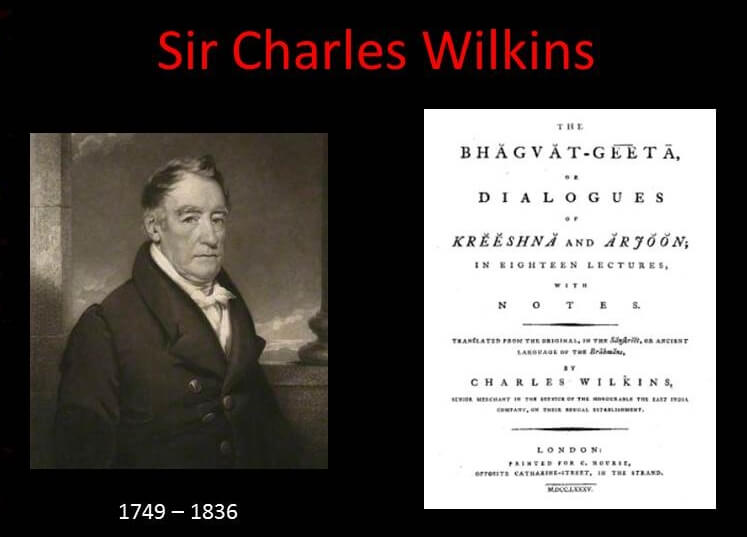

English poetry proliferated with Indian images after the translation of the Bhagavad Gita into various languages came out. It was first translated into Persian around 1556-1560 by Abu-I-Fazl and Faizi. The first translation of the Bhagavad Gita in English was done by Sir Charles Wilkins (1785) and it had a foreword by the then Governor-General, Sir Warren Hastings (1784). This was enough a reason why Gita was rendered in most of the European languages – French, German, Italian, and Russian. More so, its profound philosophical and spiritual thought greatly impressed western scholarship.

English poets like Coleridge, Emerson, Whitman, William Blake, Aldous Huxley, Yeats, and T.S. Eliot were greatly impressed by the Bhagavad Gita…

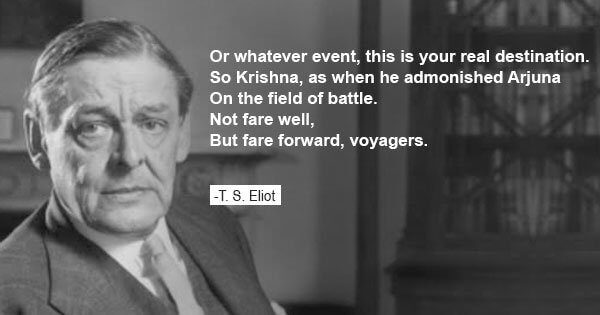

English poets like Coleridge, Emerson, Whitman, William Blake, Aldous Huxley, Yeats, and T.S. Eliot were greatly impressed by the Bhagavad Gita and other sage literature of India. They wrote powerful poems on Indian themes and made profuse use of Indian images in their works. Others like Wordsworth, Shelley, Byron, Arnold, Tennyson, Browning, Carlyle were also influenced and their works recall the transcendental philosophy of the Gita. Certainly for Eliot, the Gita was by far the most important Indic text he read and the one that most deeply and extensively informed his poetry. It was, he said, the “next greatest philosophical poem to the Divine Comedy within my experience.”

This began when the English got firmly established as administrators on the Indian land and discovered its rich heritage and the scriptures. It was then that strategies to disseminate India’s philosophy in England and other European nations were initiated. An essay on India’s history and culture written by Alexander Dow, in 1768, indicated that abundant but unrevealed Sanskrit works were worthy of England’s notice and study.

The publication of Dow’s essay was followed by two significant events.

The publication of Dow’s essay was followed by two significant events. Firstly, the founding of the Asiatic Society, in 1784, was an epoch-making event in the meeting of East and West on both the intellectual and spiritual levels. Sir William Jones (1746-1794) the first great Indologist and ‘father of Asian Studies’ invested his efforts to disseminate India’s spiritual treasures to the West through his books and the publication of the Society’s journal, Asiatic Researches. The second significant event, namely, the contributions of Sir Charles Wilkins (1750-1836) and his English translations of the Bhagavad Gita and Hitopadesha in London as well as his authoritative Sanskrit grammar, appeared soon after in 1785 and 1787 and became the basis for all later Indological work.

Wilkins loved the Bhagavad Gita wholeheartedly — he compared it to the Gospel of St. John of the New Testament. In 1785, his Bhagvat Geeta, the very first translation of the Gita into a European language, was printed in London at the direction of the East India Company upon the special recommendation of Warren Hastings. Hastings had a fascination for the Gita and he pursued the Court of Directors of the East India Company until the directors agreed to publish the work at the company’s expense. In a learned preface, Hastings wrote of Wilkins’ work, he praised its literary merits and asserted that the study and true practice of the Gita’s teachings would lead humanity to peace and bliss. The research of Gauranga Gopal Sengupta, a scholar and member of the Asiatic Society, confirms Hastings’ great esteem for the Bhagavad Gita in Indology and Its Eminent Western Savants, Sengupta writes:

Warren Hastings, while forwarding a copy of the Bhagavad Gita [by Wilkins] to the chairman of the East India Company, in course of an introduction stated that the work was “a performance of great originality, of a sublimity of conception, reasoning, and diction almost unequalled, and single exception among all the known religions of mankind of a theology accurately corresponding with that of the Christian dispensation and most powerfully illustrating its fundamental doctrines.” Well aware of the Gita’s universal bearing, Hastings included a prophetic expression in his preface: “The writers of the Indian philosophies will survive when the British Dominion in India shall long have ceased to exist, and when the sources which it yielded of wealth and power are lost to remembrance.

Later monumental works like Wilhelm von Humboldt’s analysis of the Bhagavad Gita in the Transactions of the Royal Academy of the Sciences, Berlin (1826) and the amplified Latin version made by Lassen, in 1846, from the Latin rendering of A.W. von Schlegel (1823), English translation by J. Cockburn Thomson, in 1855, and Edwin Arnold’s The Song Celestial: Shrimad Bhagavad Gita, in 1885, were a few works that further triggered the interest of the English thinkers, writers, philosophers, and translators to the insightful Indian philosophy.

Visuals by Different Truths

By

By

By

By