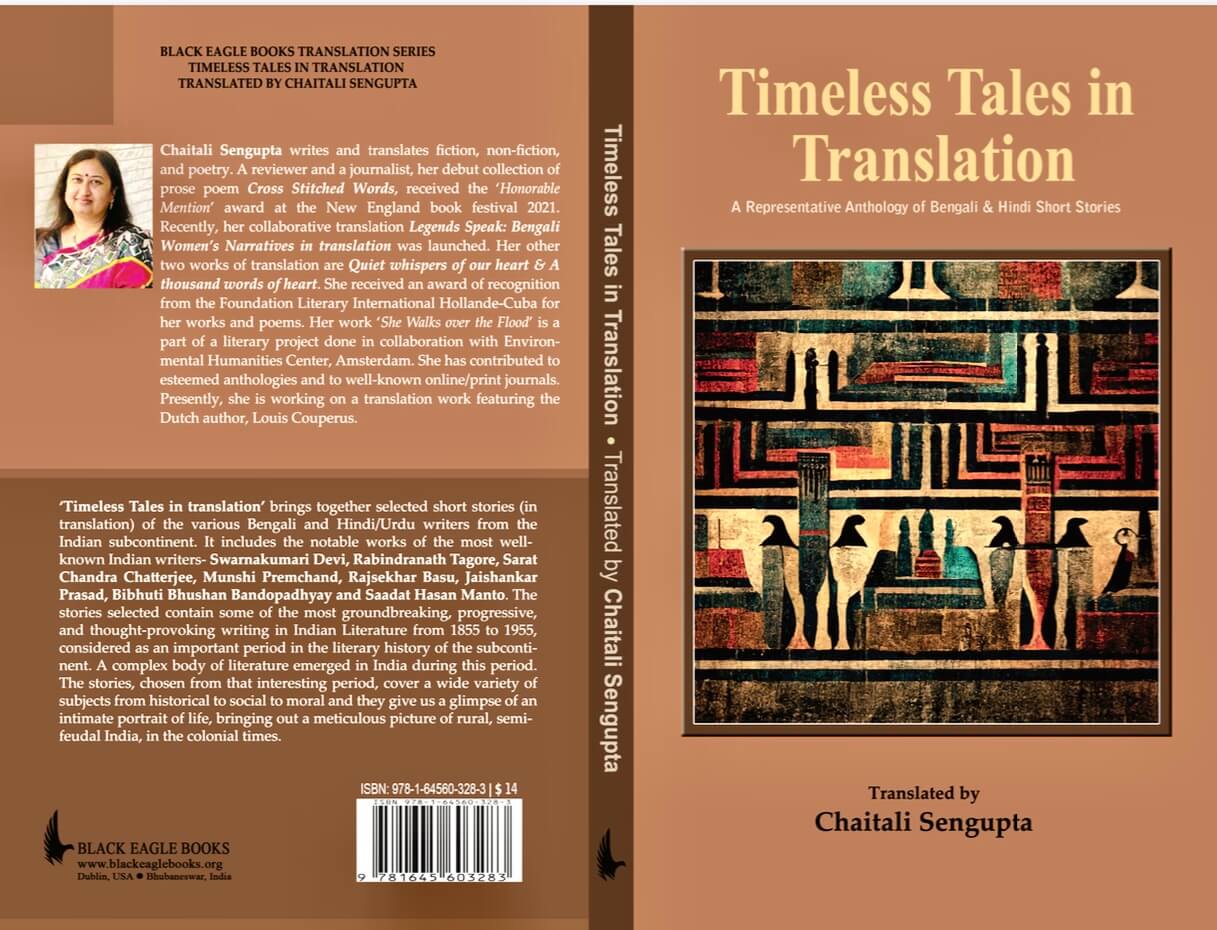

Seema reviews Chaitali Sengupta’s book, Timeless Tales in Translation, spanning a century, from stories in Hindi, Urdu, and Bangla, from mater storytellers – exclusively for Different Truths.

Translators are like architects, building bridges of communication, understanding and inclusivity across linguistic, geographical, cultural, and ethnic borders, unifying diverse people, cultures, and languages through their magic touch. Timeless Tales in Translation by Chaitali Sengupta is a unique work in the domain of translated literature, as it takes up prominent tales from the masters of the craft in Hindi, Urdu, and Bangla, spanning over a period of almost a hundred years (1855-1955). This expansive framework gives her the advantage of traversing the diversity of a country like India in the pre-and post-independence era across the socio-cultural, geographical and linguistic spectrum. The translator has discreetly chosen the tales for translation, as these tales represent the eminent writers’ varied and wide-ranging thematic concerns.

The twelve stories taken up by Sengupta are from Swarnakumari Debi, Rabindranath Tagore, Sarat Chandra Chatterjee, Munshi Premchand, Jaishankar Prasad, Rajsekhar Basu, Bibhuti Bhushan Bandopadhyay and Sadaat Hasan Manto, most of them pretty well-known, with an aim to “connect India with the rest of the world,” to “bring the English-speaking readers, both at home and abroad, to these authors and their times,” and “to give Indian tales, epics, and literature in English translation to a number of Indian young readers (who) do not read in their mother tongue anymore.” After going through these tales, translated with great finesse and accuracy, with a lot of ease and masterly handling of the target language, one feels that the translator will accomplish this avowed objective to a great extent.

These timeless tales are thematically distinct from each other…

These timeless tales are thematically distinct from each other. Each story explores some unique dimension of human experience and engages with the reader in all its intensity and richness, as the original tale would. The language, diction and idiom of translation are fluid and flow like the crystal waters of a stream, capturing the essence of the stories in vernacular. At no point does the language appear to be verbose, clumsy, or difficult to comprehend. The beauty of the translation lies in its successful evocation and recreation of the intense emotional experience that the stories convey. Some examples from the stories in this collection will amply bear testimony to the above points.

Though there is only a single woman writer in the book, Swarnakumari Debi, despite the conventional context and time in her story “Prince Bhimsinga,” the strong and assertive character of Queen Kamal Kumari, wife of Rana Raj Singha, the King of Mewar, her vociferous protest against the injustice to her son, and her dare to the King that his act will result in defaming of the family name of the Raghu clan of King Dashrath, are effectively conveyed in this translated story. Her following words to the King very well capture the essence of her independent character: “You may be the judge, but that doesn’t give you the right to be unjust. Your kingship doesn’t give you the right to break laws. And if a King does that, then he isn’t a king – he is a despot, an unrighteous ruler.” This beautiful tale of valour, self-respect, dutifulness, and justice is powerful in its translated version and touches the readers’ hearts.

The second story by the same writer, “Why?” primarily revolves around a wife’s concerns about her husband’s indifference to her because of another woman and the sudden transformation in his behaviour after her chance meeting with a woman at the temple, who happens to be none other than her husband’s paramour. The story is a simple narrative but delightfully portrayed by the translator in the target language.

Sengupta must be given due credit for her skilful recreation of the two complex and challenging tales… from … Rabindranath Tagore.

Sengupta must be given due credit for her skilful recreation of the two complex and challenging tales, “Bolai” and “Subha,” from the master of the craft Rabindranath Tagore. The sensitive and keenly observant child, Bolai’s depiction in a language that almost recreates the hypnotic spell of its original, is manifested in the following lines:

Even at an early age, he’d rather quietly observe Nature around him. The dark, billowing clouds in layers, on the eastern sky, would collect and pour. It would moisten his heart…. It was as if his entire being could hear the pitter-patter of the rains. … His joy was immense when he saw the lush carpet of the green grass sprawling down the valley… In his mind, the grass carpet was not an inanimate, lifeless thing; he felt it to be a living one that rolled down in a playful manner.

The ease and grace of the translator’s language facilitate identification with the child’s sensitive perceptions and intense emotions. Likewise, the second story by Tagore, titled “Subha”, is a very moving tale of a girl who cannot speak. This inability of the dumb child is so powerfully communicated in the target language:

When we express ourselves with words, the expression bears our own stamp…

When we express ourselves with words, the expression bears our own stamp; it is quite similar to translation, in a way. It is not always accurate, and with our inability to express ourselves, at times, we err. But no words are needed to translate a pair of dark eyes—the mind itself lends them a meaning of their own. In their depths, thoughts rise and fall, … the language of her eyes was abysmally deep, much like the clear sky, where light and shadow played eternally.

Sarat Chandra Chatterjee’s story “Ramlal’s Transformation” plays upon the readers’ undulating emotions about the mischievous Ramlal’s awe-inspiring aura and his innocence, his emotional, mother-like regard for his sister-in-law, and the responses of all other characters — all are captured with great vividness and lucidity by the deft linguistic prowess of the translator.

Munshi Premchand’s stories “The Salt Inspector” and “A Winter’s Night,” which highlight the travails of an honest man in a corruption-ridden system and the abject poverty of a farmer in the colonial and feudal India, are presented with equal dexterity and skill by the translator in her chosen language.

… the masterly handling of the stories in the target language by the translator nowhere falters nor gives way to a slackening of the readers’ interest…

Whether it is Sadaat Hasan Manto’s “Ten Rupees” about the sexual exploitation of young minor girls or the philosophical explorations of Loknath in “The Atheist” by Bibhuti Bandopadhyay, or the stories by Jaishankar Prasad and Rajsekhar Basu, the masterly handling of the stories in the target language by the translator nowhere falters nor gives way to a slackening of the readers’ interest, or obscurity or boredom. It keeps the reader hooked and keenly absorbed in the reading by virtue of its seamless recreation of the original.

Such translations as Sengupta’s Timeless Tales in Translation have a significant role to play in promoting a greater connection with these prominent authors, whose stories contain deep and perennial psychological and socio-cultural paradigms besides having a universal value and appeal. This book promises to be an immensely desirable read and deserves to be a part of the bookshelf of every connoisseur of literature.

Cover Photo sourced by the reviewer.

By

By

By

By

By

By