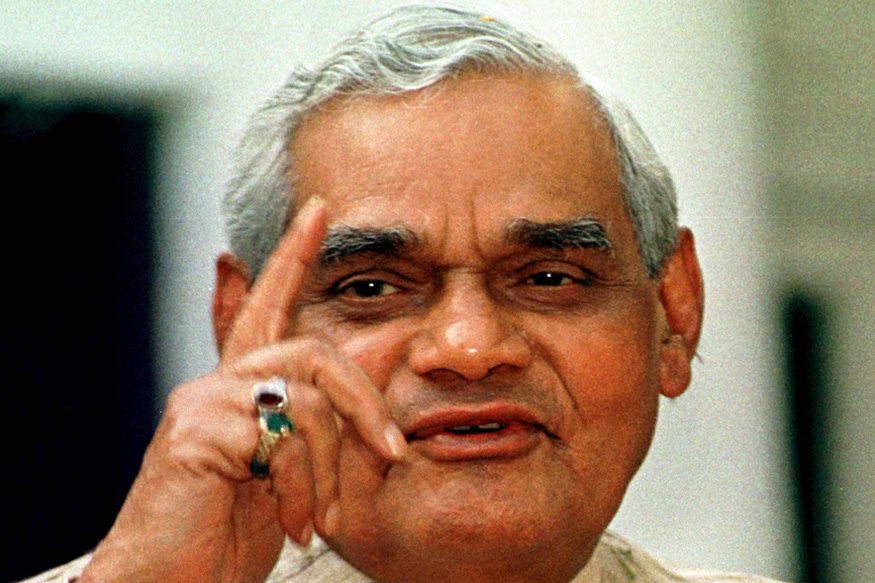

Unlike the most loved Democrat and a celebrated Liberal in BJP stalwart, Atal Behari Vajpayee, whose passing away on August 16 the entire nation mourned, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has shown himself to embracing an authoritative mode of governance with highly centralised decision-making. Vajpayee was a great nation-builder and believer in consensus-building with opposition parties on major policies and programmes. A report for Different Truths.

Whatever successes the Modi Government claims for its first four years, here and there, its major failures start with its brand of “Maximum Governance and Minimum Government”, which primarily did not ensure the “achhe din” promised in 2014. Nor, as Prime Minister Narendra Modi Government braces himself for 2019 with another set of tall promises, these seem likely to see fruition either, in a second term, if he gets it, looking to his style of politics, disorderly economics, and a harsher global climate.

The Prime Minister converted the Independence Day Address into a clarion call for fresh support in 2019, turning the Red Fort stage into a mighty nation-wide electoral platform. He sought to counter the anti-incumbency mood catching up, in the absence of real growth of the economy and proven inability to create jobs on a mass scale. For all his praise of youth and assertions of “aspirational India” on the move, there was little in his Address to generate another bout of enthusiasm as in 2014.

Unlike the most loved Democrat and a celebrated Liberal in BJP stalwart, Atal Behari Vajpayee, whose passing away on August 16 the entire nation mourned, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has shown himself to embracing an authoritative mode of governance with highly centralised decision-making. Vajpayee was a great nation-builder and believer in consensus-building with opposition parties on major policies and programmes.

In the Modi regime, we have rarely seen in practice such consultations or consensus-building with the opposition, a course proving detrimental to the country’s or economy’s interests. Throughout, in Parliament and outside, the opposition, mainly the Congress, was held to ridicule, not that the opposition for its part was blameless on any given issue.

The Leader of the House (Prime Minister) has the greater responsibility of getting major legislation enacted smoothly through a consultative process and extending a spirit of accommodation. Neither the ruling BJP nor the Chair could, in such circumstances hold the opposition parties as being disruptionist, thwarting progress on the “development agenda” of “Vikas Purush”, or obstructing politically-minded legislative pieces being pushed ahead.

To the world outside, India is proclaimed as the largest democracy. Within, we have gone through a period which has lacked norms of democratic functioning and behaviour and non-enforcement of rule of law against Hindu extremist outfits indulging in lynchings in the name of cow protection or attacks on persons by vigilante groups in the name of enforcing moral codes. The denial of rights of expression in myriad ways and violence against minorities and Dalits in distress have all been adversely commented upon in the international press, harming India’s image abroad.

Prime Minister Modi eulogising Shri Vajpayee’s qualities as poet, orator and statesman, noted that the former BJP Prime Minister (leading NDA-I 1999-2004) “defined the spirit of democracy in India”. He was always “accommodating and respectful of other points of view”, Mr Modi said and elaborated the acclaimed leader’s achievements on the economic front. The Prime Minister also described Vajpayeeji as his “Guru and role Model” and added, for a good measure, that it was his vision that “continues to drive our Government’s policy”.

But the fact remains that the Modi Government’s “majoritarianism” is a far cry from Bharat Ratna Vajpayee’s democratic governance with a gentle face, liberal outlook, and following an inclusive approach in policies and major reforms with consensus-building in a coalition government. True, Modi relatively has stood well-positioned with strong majority of his party, to have the last word in all matters of state and his party, at the cost though of widespread political criticism and murmurings within Government.

The tenor of the Prime Minister’s long statement of tributes to Shri A B Vajpayee does not suggest that Modi has much to draw anew for his Government, his contention being that it is already on the path that “Atal Ji wanted us to take…..His spirit will continue to guide us as we build the New India of his dreams”. All this sounds vague somewhat, as vague as the “New India” Modi began talking of since 2017.

Modi’s speech from the ramparts of Red Fort also sought to present a rosy view of economy with a gleeful reference to “the elephant on the move” and claimed his Government’s four-year record was better than in the UPA-II years. He picked for UPA performance 2013 as base year, a year which saw global financial markets thrown in turmoil from the “Taper Tantrum” (from a hint at a possible US Federal Reserve’s reversal of its easy money policy), when many parts of the world were still on slow recovery from the Great Recession. The Fed, however, stuck to its accommodation (pumping cash) and quiet returned to markets.

But Modi has been studiously avoiding references to his abrupt demonetisation with paralysing consequences for the economy, especially the small and medium sectors leading to loss of lakhs of jobs all over, and misery for millions deprived of cash for daily needs. He slurred over the growth setback from demonetisation for an economy which over four years has suffered from lack of private investments.

The outlook for the current fiscal year is also not as promising as it seemed at the beginning of April because of higher oil prices (with a likely additional import outgo of 26 billion dollars). The rupee has been weakening continuously in relation to the dollar (8 to 8.5 per cent by late August) and RBI has had to draw down the reserves in dollar purchases to defend our currency against undue volatility. The rupee had become the weakest among Asian currencies to suffer from the global factors, forcing rating agencies to project a higher current account deficit in India’s balance of payments at 2.5 percent of GDP in 2018/19. Overall macro-economic stability continues to remain fragile despite a favourable monsoon and some revival in manufacturing tempo. Still, we pride ourselves being the “fastest-growing economy” in the world.

S Sethuraman

©IPA Service

Photo from the Internet

By

By