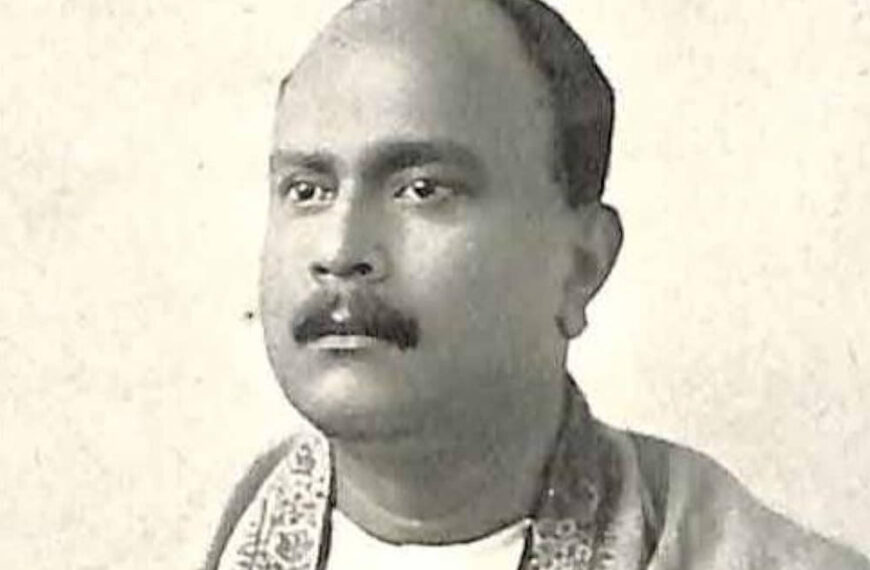

Khushwant Singh’s Train to Pakistan tells the story of Jagga, a village dacoit who upholds his code and protects his village during the Partition of India, deliberates Azam in the second part – exclusively for Different Truths.

It took more than the entire decade of Field Marshal Ayub Khan’s governance for Khushwant Singh’s Train to Pakistan to reach Lahore, and to this day, I don’t know how it did. It just might have been an R&AW conspiracy to project Indian soft power. However, R&AW was still struggling in the labour room at that time, and the Indian Intelligence Bureau had never been reputed for being intelligent!

A year before Train started shunting around Lahore, the movie, The Long Duel, starring Yul Brynner and Trevor Howard, had scored at the box office, more so since it was generally held that it celebrated a 1920s heroic Muslim Robin Hood of undivided India.

They’d got it wrong!

It was the story of Sultan Singh, chief of the Hindu Bhantu tribe of Uttar Pradesh and the Terai, which traced its descent from Maharana Pratap of Mewar, the folk hero who resisted Mughal Emperor Akbar’s expansionism. The movie was based on a story by Ranveer Singh (not to be confused with the movie star married to Deepika Padukone and nephew of the late Samuel Martin Burke, Foreign Service of Pakistan, the pride of village Martinpur). A year after the movie’s success, coinciding with the launch of the dacoit Jugga, Khushwant Singh’s protagonist in Train to Pakistan, Lahore’s very own living Jagga, Mohammed Sharif Gujjar, was imposing his Jagga Tax on the abattoirs of Lahore!

With the deadly efficiency of the t’hai-pha’at (two and a half strikes) tactics of a Khalsa assault, Train to Pakistan pierced through these competing elements, reducing them to the status of heralds trumpeting its entry.

Appointing a Punjabi dacoit as the protagonist was one of Khushwant Singh’s many master strokes…

Appointing a Punjabi dacoit as the protagonist was one of Khushwant Singh’s many master strokes, so subtly executed that it has languished unrecognised. Jugga, although a small-time village dacoit on the Train to Pakistan, upholds the dacoit’s code and protects his village. He opposes his fellow Sikhs to defend the landless Muslims fleeing to Pakistan, hoping to claim land left vacant by migrating Hindus and Muslims, sacrificing his life for his principles.

And joins the pair of senior Jaggas on whom Khushwant Singh grafted him.

Jagat Singh was a Sidhu Jatt, aka Jagga Daku and Jagga Jatt of the 1920s and 1930s, and Jagat Singh, a Cheema Jatt of the 1940s aka Jagga Daku, Jagga Jatt and Jagga Cheema, his successor by acclamation.

The rural dacoit of South Asia might be a stock character in Bollywood movies, but in English novels, Train to Pakistan was a first, making it The Long Duel’s print precursor.

The first Jagga is enshrined in a ballad still sung by bards. And since Firozepur district is in Indian Punjab and Qasur district in Pakistan, the name Jugga in Train to Pakistan reunites divided Punjab, with or without authorial intent.

Neither the real-life Jaggas nor the Jugga of fiction died natural deaths.

The original Jagga had been treacherously assassinated; his throat slit as he slept.

The original Jagga had been treacherously assassinated; his throat slit as he slept. His immediate successor, Jagat Singh Cheema, was hanged from Eminabad, district Gujranwala, now in Pakistan.

Jagga Cheema started weeping during his trial.

He answered the magistrate’s question: “I weep for the witnesses’ wives and children, sa’ab bahadur…” Yet even though his witnesses retracted their testimony, he was sentenced to death and went to the noose singing and taking bhangra dance steps.

Both these Jaggas were Jatt.

The next in line came in Lahore in the late 1960s, who was neither a Jatt nor a Sikh.

This Jagga levied Jagga Tax, often pronounced ‘task‘ of one rupee per sheep slaughtered in the sheep-market abattoirs of Lahore!

Mohammed Sharif Gujjar’s uncle Buddha (hard ‘d’) Gujjar baptised his nephew with the sobriquet Jagga Gujjar. This Jagga levied Jagga Tax, often pronounced ‘task‘ of one rupee per sheep slaughtered in the sheep-market abattoirs of Lahore! His name resonated in Lahore at the time Tabi slammed Train to Pakistan on the Lucas Centre café’s tea table.

Shortly after, Jagga Gujjar was killed in classic police ‘encounter,’ known as ‘puls muqabla.’

And herein lies another of the many nuggets of Khushwant Singh’s marked genius and Punjabophilia.

He illustrated the human tragedy of Partition within the Punjabi rural framework of hereditary banditism. Jagga’s father and grandfather were also dacoits, his father Alam Singh was hanged, but they lived by the dacoit’s code of honour. That honour, sustained by a village dacoit and not feudal chiefs, glimmers through the dishonour that created Trains of the Dead in either direction.

In Lahore, the species of Indian authors were as rare as Bollywood movies — at least officially.

1968, the year Indira Gandhi lifted the 1962 emergency imposed by her father, was also just three years after the second Indo-Pak war. In Lahore, the species of Indian authors were as rare as Bollywood movies — at least officially. The intellectual space of youthful, English-medium, politically neutral Lahore was swamped with Sadat Hassan Munto, Patras Bokhari, Munshi Prem Chand, James Baldwin, Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, Somerset Maugham, Dos Passos, G. K. Chesterton, John Ruskin, Harold Robbins, Peter Cheney, Leslie Charteris, John Creasy, Harold Robbins, Grace Metalious, James Joyce, T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, Henry James, Denise Robbins, Barbara Cartland, Agatha Christie, Sherlock Holmes, James Hadley Chase, D. H. Lawrence, Johnson and Master, M. D. Harris, Alberto Moravia, Camus, Sartre… phew!

They shot out of our heads to land on the FC College Lucas Centre tea table, but each had to cower under Khushwant Singh, who flapped higher and higher, leaving them to dance like dust devils under the triumphant flash of the sirdar’s teeth in his dark beard.

And we, too, stood tall under Khushwant Singh’s Punjabi shadow.

To most of us, Khushwant Singh was the first South Asian and fellow Punjabi to have written not some treatise on birds and bees, nor Indian mysticism, nor esotericism, nor an ‘engagé’ novel within a pre-determined, class-conflict framework, but a work of didactic art that brought one of history’s most cataclysmic events to the fore, while sustaining Philip Sidney’s criteria of entertainment and instruction.

Yet, Train to Pakistan had been published in 1956, two years before General Ayub Khan’s coup d’état, which was to promote him to Field Marshal…

Yet, Train to Pakistan had been published in 1956, two years before General Ayub Khan’s coup d’état, which was to promote him to Field Marshal a year later. In retrospect, we learned how well it had been received in the outside world, but it was buried under deafening silence in our immediate vicinity.

The core of Steinbeck’s 1962 Nobel award was The Grapes of Wrath, the USA’s dustbowl tragedy of the 1930s, affecting “tens of thousands,” yet the dustbowl’s scale of suffering pales in comparison with that of India’s Partition and the creation of Pakistan, with Collins and Lapierre estimating, in Freedom at Midnight, close to a million deaths, excluding the millions of displaced and shattered families. Yet not a single Partition novel has ever succeeded in drawing the attention of the Nobel Prize Committee.

Even after Khushwant Singh and Train to Pakistan somehow started making the rounds of the student community in 1968/69 Lahore, our professors skirted the subject, and there was no question of including it in the coursework or even as an oblique reference in class. There was an official Partition main dish, and the side dishes were unwelcome.

There were five additional reasons for this.

The writer was a Sikh, and Sikhs had been killing Muslims in 1947, so a Sikh could not be given his due…

The writer was a Sikh, and Sikhs had been killing Muslims in 1947, so a Sikh could not be given his due — it took seventy years for Bhagat Singh to get a chowk square named after him in Lahore, at the spot where he had been hanged in the struggle to liberate India and present-day Pakistan from the British.

The hero, too, was a Sikh and not in the mould of Kartar Singh in the 1959 Pakistani movie of the same name.

The writer was an Indian, and they were considered sworn enemies.

The hero was a dacoit, and that would never do — naughty!

That he was a proletariat meriting progressive attention was blissfully ignored, even in Pak Tea House, the watering hole of Lahore’s progressives and Lahore Arts Council, Alhamra Centre, their redoubt.

It doesn’t explain why Ajab Khan Afridi (of Miss Alice fame and subject of the 1961 Pakistani movie with the same name, starring Sudhir) and Sultana Daku, both outlaws, were household names — Sultana even being unilaterally dubbed a Muslim, despite being a Hindu.

But the worst is yet to come: a Sikh man having a torrid affair with a Muslim girl in the sugarcane fields of Punjab — doing it! That was taken as a mortal insult and a threat to decency’s ideological foundations and boundaries.

Yet, it doesn’t explain why, despite the politically correct Muslim-boy-Hindu girl, The Heart Divided, by Mumtaz Shahnawaz, published posthumously by Mumtaz Publications and printed by Ferozesons, Mall Road, Lahore, in 1957, disappeared after its very brief appearance. On 15 April 1948, the author had been on Pan Am Flight 1-10 to represent Pakistan at the United Nations general assembly and carrying the manuscript of The Heart Divided for submission to a prospective publisher when the plane crashed over Ireland, killing her and all but one of the passengers.

So, in 1948, the author finished the manuscript of The Heart Divided.

This basis would make it the first English novel on Partition.

The publication date, however, positions it as the second, after Train to Pakistan.

It is puzzling that this sensitivity-conscious Muslim-boy-Hindu girl story could not make any headway at its birth…

It is puzzling that this sensitivity-conscious Muslim-boy-Hindu girl story was unable to make any headway at its birth, just as Khushwant Singh’s Sikh-boy-Muslim-girl affront had been shut out.

Train to Pakistan had to wait a decade for its resurrection. Still, The Heart Divided, written by a Muslim maintaining the acceptable interfaith relational parameters, had to wait thirty-three years to be resurrected, first by ASR Publications, Lahore, in 1990 and finally by Penguin India in 2004, in which country it had a pretty successful run.

This jigsaw puzzle will continue to titillate primatologists until one of them is successful.

More so, since Masters and Johnson’s books on sexuality, Fanny Hill, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, The Perfumed Garden, The Invisible Government etc., were openly displayed at bookshops, as was ladies’ lingerie in the shop windows, but not Train to Pakistan, The Heart Divided, Kama Sutra, etc. Official censorship guidelines and preemptive self-censorship in authoritarian and mediocre governance expose self-contradictory chaos, generating illogical fears and uncertainties among simple folk.

And mind you, this one can’t be hung at General Zia ul Haq’s door to cry victimhood at dictatorial hands. In 1968, Zia, a hereditary market gardener, was a colonel or a brigadier, counting himself lucky to have been able to get that far in his career at a time when Zulfikar Ali Bhutto (ZAB), fated or ill-fated to crown Zia’s career at the cost of his own life, was launching his People’s Party, for which he climbed down the steps of his aircraft at Lahore, chanting the tweaked Sindhi celebratory folk song “Bhutto aa gaya maidan mein, hey Jamalo,” (Bhutto’s entered the field — oh the beautiful) to which college girls gasped “hai, how cute, nah!”

Wage earners squatting on peerdhi stools at dal-roti tandoors sang, “P’huttoo aa gaya madya’an wich, bach Jamalo!” (Bhutto’s entered the field — watch it, beautiful!).

This crowd had never heard of Khushwant Singh’s Train to Pakistan…

This crowd had never heard of Khushwant Singh’s Train to Pakistan, though one might give ZAB himself the benefit of the doubt — if Mein Kampf, why not Train?!

Some professors we met in cafés or eateries would enter the Train conversation, but it was always carefully worded, and they wiggled out of it at the first opportunity. Everybody was wary of CID informants and the ubiquitous plainclothes police — chitti-kaprdhee pulsias.

However, since Partition hit its half-century, a pile of fiction has been building up on this event, though the stories are within the standard framework.

Yet, my novel Blasphemy: the Incident, the ethos of which is the Christian community living under one-sided blasphemy laws, also deals with Partition and post-partition smuggling, bringing prosperity to small farmers.

Novels like Shauna Singh Baldwin, Kamla Shamsie, Yasmin Khan, Anita Desai, Niaz Zaman, Bapsy Sidhwa, Amitav Ghosh, Attia Hossain, Kamleshwar, Krishna Baldev Vaid, and other works of fiction, biographical fiction, and non-fiction, proliferate with impunity.

It was at the British Council Library, in 1968, where I went to see if they had Train to Pakistan — they didn’t, not at that time — that I learnt of Khushwant Singh, the scholar offered by the harried librarian as a substitute for Train to Pakistan, which he claimed to be too busy to discuss! No complaints, considering …

To be continued

Picture design by Anumita Roy

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By