The partition of India is a deep gash in our collective consciousness. Millions of people from West Punjab and East Bengal were rendered homeless. There were hunger, rape, loss of human dignity and property. There were mass murders. Women and children were not spared either. Trainloads of dead bodies crossed the borders. Lily recounts the experiences of her ancestors, her grandfather, father, aunts and mother-in- law. If there were the memories of agonies, so also the cuisines from Muslim kitchens or pre-partition Punjab that still lives on, in the author’s mutton korma. Here’s an exclusive in Different Truths.

She had covered her face in a long ghunghat or ghund, the Punjabi word for a veil that keeps your face incognito. It was the scalding searing heat of the August of 1947. My mother-in-law, a young slip of a girl, with two children was running for her life, behind caravans of other Hindus and Sikhs, who were fleeing from what was to emerge as a new country Pakistan! Girls married rather young those days! Beeji, as we called her, is a short form of Bibi Ji, which is respectful way of addressing a lady, was huffing and puffing with one baby (my sister-in-law) in her aching arms and another two-year-old clutching her finger (my brother-in-law ).

Blinded by her veil and doggedly following her father-in-law’s footsteps, she raced on! Terrified out of her wits, for she feared losing the only familiar face in the vast expanse of humans! To add to her misery, she realised to her horror that her husband’s father had never seen her face! It was customary in Punjab those days (well, still is in some rural areas) to hide your face from any man other than your father or husband! How on earth would her father-in-law find her in this bone crushing melee? She hoped in her praying heart that he would remember the colour of her clothes! They were trying to cross over from Kasur.

As the struggle to board the train ensued she heard her father in law whisper, “Child please uncover your face!” Well, she did. Generations and eons of customs fell away, as she pushed back her chunni (veil) over her head, letting the kind but flustered father figure look at his petrified daughter-in-law’s face for the first time! It seems when the train crossed over and reached Ferozepur, he said again benevolently, “Child, pull down your veil.”

Amidst the blood curdling stories of man killing man! Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs brutally raping the women of the other community, this remains the bright spot for me! My Beeji told me that this remained a secret between her father-in- law and her and that I was the first one to hear of it!

Sometimes conversations in the kitchen live with you! I have cherished this in my heart all these years.

Lakhs of people lost their homes, coming penniless and in summer attire, little realising that they would never see their homeland ever again.

My Beeji was smart. She put all her gold in a little cloth pouch and tied it around her waist safely tucked in her salwar, the Punjabi version of stringed trousers. That gold helped marry off all her four young sisters and one brother in the new country, India. No one ever went back.

My dad had just passed his matriculation that year, from Khalsa School, Sargodha. A boy with a new moustache cropping up on his upper lip, when they left their ancestral home in Sargodha. My grandfather was a renowned lawyer with a roaring practice. There was commotion and unrest. It was escalating. I was told that my grandfather felt that if they took a small vacation in the summer holidays the heat and dust would settle and then the family might return once again. They tied up their summer apparel, got on to a tanga (a two-wheeled horse-driven light carriage) to vacation at Amritsar. Little did they realise then that it was their goodbye to the town, which was their own. Their huge house was grabbed by the Muslim tenants, as they grabbed a house in Jalandhar that was vacated by those, who left their hometown, for Sargodha. One of my aunts studied in the prestigious Kinnaird College, Lahore. She was also hastily summoned from the hostel.

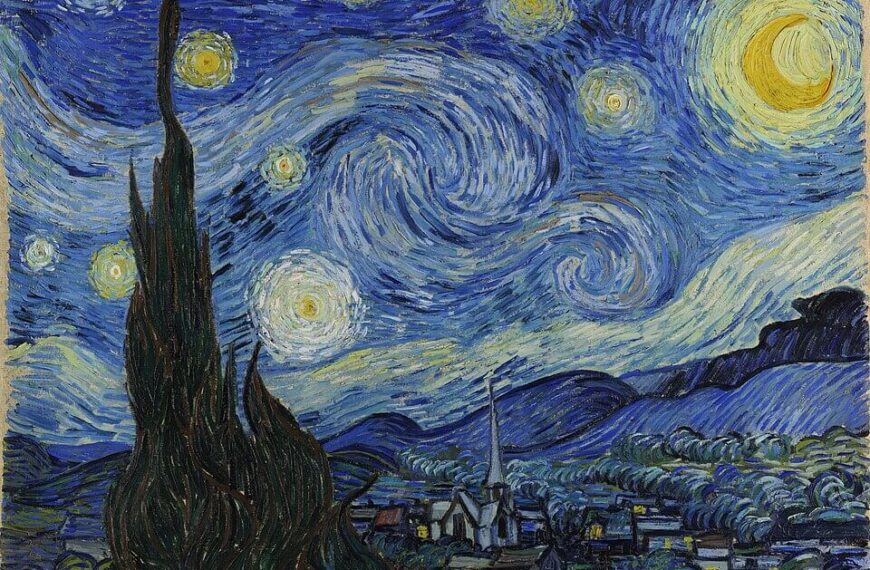

Published caption: After independence, millions of Muslims and Hindus fled across the Pakistan-India border, many on trains. Communal violence killed more than a million people.

Life restarted by feeding many homeless refugees in Amritsar refugee camps as my grandad was lucky to get a job. My father says that he was ashamed to see Sikhs beheading Muslims outside Gurdwara Pipli Sahib, in Amritsar. Blood boiled as reports of Muslims killing trainloads of Sikhs reached Amritsar.

There were trains from Pakistan where almost everyone was killed. There were sounds of blood curdling shrieks and rivers of blood. People preferred to walk all the way across the supposed borders or ride bullock carts.

My mother-in- law was nursing a child. Since there was no food or water for miles, no milk flowed from her breasts. Her baby was dehydrated. She recounted with tears in her eyes that the toddler, who trotted beside her was miserable with hunger too. The train was totally sealed. Soldiers, who were guarding the train were banging their rifle butts if anyone tried to open the window for some fresh air. Humans were stuffed like sheep and goats. The trauma lived on, in the form of agonising tales.

I have inherited this trauma of displacement without having witnessed it, as I grew up hearing the horrifying stories where humans lost their dignity along with their lands and homes. It is laudable and creditable to the wondrous waters of the five rivers of Punjab that these homeless penniless people sold wares on the roads but never begged on both sides of the border. My relatives are examples of the sheer grit and determination that lives inside this hardy resilient race. They have the some of the biggest palatial homes in Delhi and all over India, now. They created new lives and carved new homes, wherever the train stopped. Right up to the south of India, you will see a Punjabi refugee, who still lives in his heart in what is now Pakistan.

When my dad visited the Gurdwaras, in Pakistan, he was misty eyed. The love between the people remains strong. They grew up together as brothers. They share a common culture of similar food, attire, folk songs and dances. They love in the same robust back slapping manner. They even curse and abuse identically in Lahore and Amritsar.

The streets look and smell the same. The girls giggle and whisper the same. I wish I was a bird, so that I could fly off across too to see the land of my self-respecting ancestors.

It no small wonder that the flavour and love of my granny’s best friend, a Muslim woman, Mehnoodaan, is still alive in my mutton korma, after all these years of partition! History and fate might tear us apart, but the culture and the deep connection can never be severed.

For those who have not seen Lahore are not even born goes the saying in Punjabi, “Jine Lahore nahi vekheya oh jammeya hi nahi!”

©Lily Swarn

Pix from Net.

By

By

By

By

By

By

It’s a well known fact of history that the partition of Indian subcontinent resulted in the displacement of 14 million people along religious grounds. The untold affliction was witnessed by me yesterday evening once again in Gurinder Chadha’s film, Viceroy’s House.

An interesting revelation in the film relates to the covert plan to draw the boundaries of Pakistan with a view to carving out a buffer state between the Indian subcontinent and the Soviet Union. To the utter anguish of Lord Mountbatten, he finds himself used as a pawn at the altar of the hapless millions.