In Latin America, there is a tradition of women’s rights activism. Commitment to gender equality is not new in Latin America. In fact, Latin women’s empowerment has reached beyond frontiers all the way to the global scenario. For instance, the influential heritage of Latin American women writers is strongly present in literature. A relevant example is the fact that of twenty-six writers chosen as contributors to 1972 UNESCO publication, Latin America in its Literature. Here’s Luz María’s erudite narrative about the rich heritage of Latin American women writers, as part of the Special Feature. A Different Truths exclusive.

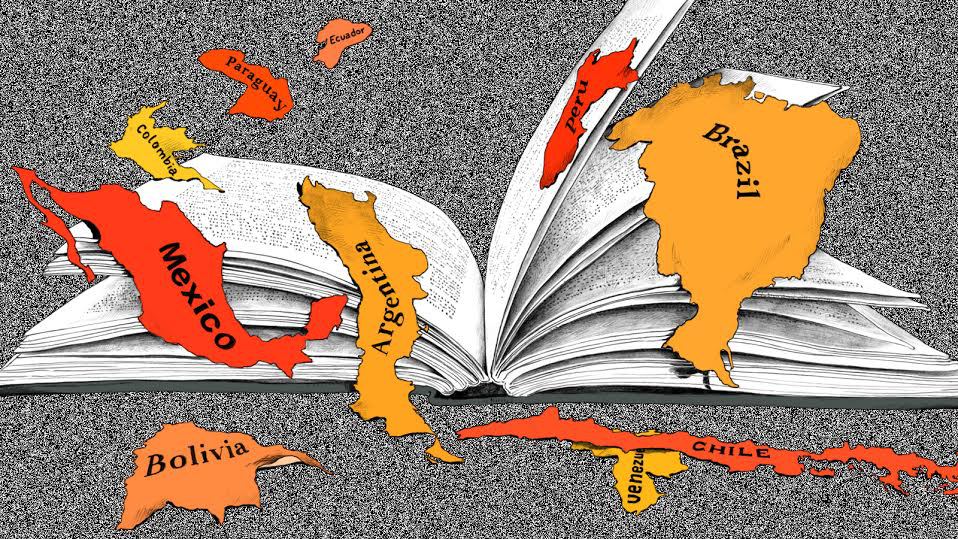

Everywhere in the world, women face discrimination and violence. In many countries, criminal and civil law even abide by such discrimination. In fact, in countries where women have achieved equal rights, this often remains as illusory. In terms of political and public representation, women are still largely underrepresented. However, women are not only victims but are also the main architects of their own emancipation. In Latin America, there is a tradition of women’s rights activism. Commitment to gender equality is not new in Latin America. In fact, Latin women’s empowerment has reached beyond frontiers all the way to the global scenario. For instance, the influential heritage of Latin American women writers is strongly present in literature. Nonetheless one must point out to discrimination. A relevant example is the fact that of twenty-six writers chosen as contributors to 1972 UNESCO publication, Latin America in its Literature, there was not one woman represented!

Hombres necios que acusáis a la mujer, sin razón, sin ver que sois la ocasión de lo mismo que culpáis… (Hombres necios, Redondillas, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz). Foolish men that accuse the woman, without reason, without seeing that you create exactly that for which you blame them… Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1651-1695), Mexico, set precedents for feminism long before the term or concept existed. Today she stands as a national icon of Mexican identity and has been officially credited as the first published feminist of the New World. Her fierce assertion of a woman’s right to fully participate in scholastic inquiry marks her as a philosopher as well. In the same decade that England’s Mary Astell wrote her argument for the education of women, A Serious Proposal to the Ladies…, in Mexico, Sor Juana was hotly defending a woman’s right to an education and intellectual prowess in Reply to Sor Philothea. Mexico renders also multi-awarded Elena Poniatowska (born 1932), a journalist and author. Her role as the voice for the oppressed had taken her to write about women’s issues. Many of her female characters are at the mercy of men for their lives are ruled by a world made up of double standards. In “Urgencies of a God” (Mexico, 1950), by magnificent poet Enriqueta Ochoa, a personal theology contrary to institutionalized religions scandalized society at that time. Just a line from her poem: Seek no further myths in my lips.

If one asks Gioconda Belli, a Nicaraguan novelist-poet author of The Inhabited House, if she writes about women’s issues, she will reply that her literature is not feminist, is a literature in which the woman is the protagonist. The vision of the world through the perspective of the women is a powerful way to convey social awareness of the struggles of Latin American women and women in general. And yes! Women can be great political strategists. Policarpa Savalarietta (La Pola), for instance, is the Independence of Colombia heroine! She was executed in 1817 accused of the traitor by the Spanish Militia. Before her death she delivered a heartfelt speech invoking to the bravery of actions: “See that, woman and young, I have more than enough courage to suffer this death and a thousand more. Do not forget my example.” In Honduras, there was another formulation of a revolutionary poet, Clementina Suárez (1906-1991). She is essential to anyone interested in the history of feminism in this Central American country. Her bohemian lifestyle and unorthodox poetry caused the public to view her as a controversial figure. She ran completely counter to standards of behavior expected from women of her time. She divorced twice stating that marriage interrupted her career, thinking, and her way of life. In 1970, she received the “Ramón Rosa” National Prize for Literature.

Gabriela Mistral, laureate poet from Chile, echoes ideas of female connectivity associated with radical cultural feminism, as seen in her poetry. In her collection of poems entitled Tala (Destruction), published in 1938, she laments the destruction of her own beliefs, hopes, and well-being through themes including death, childhood, and maternity. Mistral depicts motherhood as an act of self-preservation, a liberating experience. This undoubtedly empowers all women by changing motherhood from a subordinate role in support of patriarchy into a position of power in support of women’s nurturing and caring roles. Alfonsina Stormi, Argentina, on the contrary, held a status as an unwed mother and social rebel. With a body of poetry that touches on vital women’s issues, her name came to be a symbol for generations of Latin American women. Like so many female writers before her, Stormi defined herself as a prisoner of her gender. Indeed, some of her most famous poems, such as Little Man and You Want Me White, forcefully protest and subvert gender hierarchy in a male-dominated society. Alejandra Pizarnik (Argentina), an iconoclastic poet, however, struggles with solitude; she is helplessly in search of some perfect counterpart never found. Her diaries are a record of her emotional life, including depression and continual suicidal ideation. Her life is a venue of surrealism, feminism, and psychoanalysis of women for many scholars nowadays.

Cristina Peri Rossi from Uruguay explores the repercussions on the male sexuality of a patriarchal and phallocentric society, themes which come to be explored in later texts, such as Love is a hard drug (1999). Sônia Coutinho (Brazil) was awarded the Jabuti Prize, in 1979, for the anthology, The Poisons of Lucrecia (1978) which contained her short story Cordelia, the Huntress. This text also won the Status Prize for erotic literature. Her feminist ideologies are most notable in her critical writings and her commentaries on gender relations in Brazilian society. From Cuba, Excilia Saldana, amazing and thought-provoking poetry, engaging with race, gender, and all that these entail in the process, won 1998 Nicolás Guillén Award for Distinction in Poetry. Her anthology, My Name: A Family Anti-Elegy (1991), talks of denying the traditional motherly role of the bourgeois family, instead positioning women as the mothers and creators of revolutionary Cuba. In Puerto Rico, Ana Roque de Duprey opened the academic doors for the women in the island. Roque was a suffragist who founded “La Mujer” (The Woman), the first “women’s only” magazine in Puerto Rico at that time. She was one of the founders of the University of Puerto Rico in 1903. Another Latina feminist to remember is Julia de Burgos (Puerto Rico, 1917-1953), one of the greatest female poets in Latin American history and the world. Predating the Nuyorican poetry movement, she engaged in themes of feminism and social justice. Her feminist Afro-Caribbean thoughts allow to read her as a precursor to contemporary Latin female writers as well. Besides poetry, or because she was a poet, she became a women’s rights advocate and libertarian. Julia’s life had all the passion and tragedy associated in the popular imagination with the greatest poets, culminating in her inexplicable death at age 39 in a New York City street and burial in potter’s field. She was her own route…

I wanted to be like men wanted me to be:

an attempt at life;

a game of hide and seek with my being.

But I was made of nows,

and my feet level on the promissory earth

would not accept walking backward

and went forward, forward,

mocking the ashes to reach the kiss

of new paths.

I was My Own Route

Julia de Burgos

(fragment)

Nowadays, Latin American female narrative explores transgression issues by means of “globalised” minds, which in turn is directly connected to a cultural, historical and political interpretation of the world. As Leela Gandhi asserts in her book, Postcolonial Theory: A Critical Introduction: women have suffered a “double colonisation”; the “third world woman” is a forgotten casualty of the imperial ideology, and native and foreign patriarchies (83). Many scholars agree that postfeminists’ representation is exploring new gender directions within the frame of a new discourse. Therefore, these writers from Latin countries have become the voice of a multitude of women fighting biased social construction and male chauvinism. They have also appropriated a language of their own, a language of the human psyche and co-existence. Because of that, the literary canon of our time (past and present) has been enriched. There are many Latin American women writing great literature in vernacular language and they are changing the way literature is professed.

Photos from the Internet and image by Anumita Roy, Different Truths

By

By

By

By

By

By