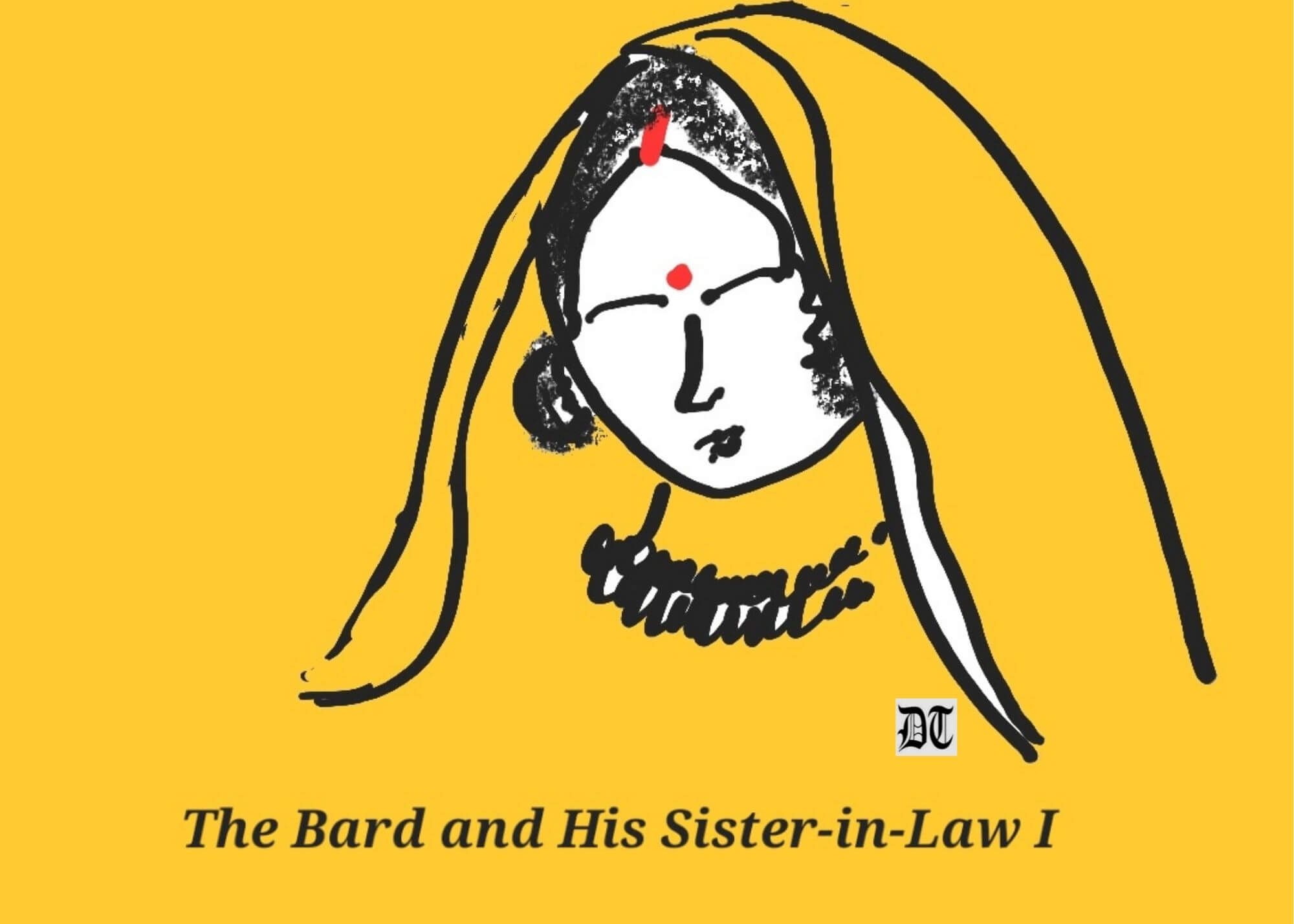

Lopamudra translates Mallika Sengupta’s, a renowned Bengali poet and novelist’s biographical novel, Kobir Bouthan (Bard’s Sister-in-law). Here’s the first part of the two-part excerpt — an exclusive for Different Truths.

Chapter 1: Gyanada Nandini

One fine day in the Bengali year 1866, a horse carriage stopped in front of the main entrance of the illustrious Jorasanko Thakur bari of Kolkata. As the carriage door opened, one could see two dainty legs adorned with fancy shoes and socks stepping on the ground. Over the legs, the pleats of her finely embroidered rust-coloured sari fell over, drooping like a sweet surrender. She stood firmly on the floor of her in-law’s ancestral home, the sixteen-year-old vein of lightning, and started walking towards the inner quarters of the house. That day, with the bold, unabashed emergence of Mejo bou Gyanada Nandini, the young bride of Jorasanko Thakur Bari, in broad daylight, right in front of its bevvy of servants and attendants, the inner quarters of the mansion had shaken to the core, like a sudden earthquake.

The old servants of the household, who hadn’t witnessed such a scene before, wailed in despair as if they had experienced a bad omen. Manada dashi, the maid servant, peeped stealthily from the quiet nooks inside the house, absorbing the scene and ran quickly to inform Karta Ma, the mistress of the house about this incredible phenomenon. The male stewards and agents of the estate stood with glum faces. Their dear Mejo Babu had just been back from Bombay after a long, long time, and he had entered his home together with his young bride, which they knew, was the most unusual event that had happened in this household, especially when Debendranath, the master of the house was absent. They had their mouths sealed, but they had no doubts that the aftermath of such a phenomenon would be tremendous.

The second son of Debendranath, the master of Jorasanko Thakur bari, Satyendranath was a meritorious scholar of those days.

The second son of Debendranath, the master of Jorasanko Thakur bari, Satyendranath was a meritorious scholar of those days. He was the first Indian man to crack the Indian Civil Services examination and become an I.C.S. officer. Not only was he gifted academically, but he also was instrumental in various thoughts and acts regarding women’s liberation. When he was married to Gyanada, she was a child bride of seven, according to the ‘gouri‘ daan’ rituals of the old times. She had just been initiated into the Bengali alphabet in her maternal home then. SatyeSatyendra’st to attain the emancipation of women had started during those days, along with his naïve child bride dressed up in a sari, with her head covered in a veil, her nose adorned with a nolak (nose ring). From a very young age, Satyendra’s unwavering protests were against the imprisonment of women within the four walls of their home, even in the nineteenth century. He would often insist his mother Sarada Debi step outside the peripheries of their home and see the outside world. Sarada, with orthodoxy deeply rooted in her blood, would admonish him.

“Will“the women of our house roam around with you in the open field of Maidan now, like the mem sahibs (English women)?” She would blurt out.

“So, what, if they end up going there?” Satyendra’s young mind was inquisitive.

“If they ever do, it will only taint the sanctity of the household. Don’t you know, even the men of our house don’t venture inside the inner quarters at their own will unless night falls and it is time for them to sleep? Has anyone ever heard of the women of such a household as ours roaming around in the open, along with the men? They will be ridiculed if that ever happens!”

… ”he mejo bou … had now morphed into a bright, emancipated lady.

Many years have passed after this conversation, or rather, an argument between mother and son. Meanwhile, the mother has been more rigid in her orthodoxy, and the son has been more liberal, and progressive. And his young, docile bride, the mejo bou had witnessed many a storm in her life along with her invincible ICS husband, having lived in Bombay with him for two years. She had now morphed into a bright, emancipated lady. When she stepped inside the inner quarters, her mother-in-law Sarada Debi’s sombre face became darker, seeing her emerge as the anglicised shadow of those mem sahibs she had heard about. She participated in the welcoming rituals of her son and daughter-in-law with her austere face, surrounded by fourteen or fifteen girls and women of all ages, all belonging to the Thakur bari clan. With curious, gaping eyes, they witnessed the bride who had sailed in a ship all the way from the shores of Bombay to Calcutta. There were ripples in GyanaGyanada’s too, looking at the awkward gestures of these girls and women, their attires and their demeanours. She strongly felt that the souls, the ‘persona’ of ’these girls and brides were buried under the heavy burden of their saris and ornaments. She looked intently at a young teenage girl, her heavy Banarasi sari entangled with her legs. She noticed a bride’s beautiful body covered in the shameless jingling sound of her gold ornaments. She also noticed that with all this grandeur of their attires and ornaments, their voluptuous femininity came out like gushing fountains of youth. It was really impossible for them to come out in the open in these attires, to subject themselves to the male gaze.

Right then, she guessed perfectly well why it was forbidden for the men of the household to step inside the inner quarters during the daytime. Saradasundari Debi, her mother-in-law had reclined her body over a pillow, seated on a large bedstead in her room, her soft muslin sari, the colour of sandalwood, looked much like her second skin. Looking at her face, Gyanada remembered all her bittersweet memories with her mother-in-law. The fact that she couldn’t be tamed by her mother-in-law the way she wanted, made young Gyanada suffer her harsh words many times. But she had memories of her mother-in-law tending to her as a child, trying hard to enhance her beauty and health. The memories of the child Gyanada sitting on the bedstead, watching the maids of the house applying maida (flour) and milk cream on the faces of the brides reappeared in her consciousness. She remembered her thin, dusky childhood form which her mother-in-law disliked. She had made it her mission to groom Gyanada, beautifying the child bride, making her a befitting bride of the Thakur bari in all aspects.

The young brides of the Thakur bari looked dull and unappealing… she remarked.

The memories of a day flashed in front of GyanaGyanada’s when the brides of other households came to pay a visit to the Thakur bari. Her mother-in-law had regretted, noticing the healthy, robust appearances of the brides. The young brides of the Thakur bari looked dull and unappealing, like wooden stakes with their lanky features, she remarked. She had sworn to make Gyanada healthier, fuller. She started feeding rice to her daughter-in-law, preparing the morsels herself. The veiled child bride felt embarrassed, unable to either gulp or throw away the rice. While the mistress of the house approached her daughter-in-law’s mouth with morsels of rice in her nimble fingers, the child bride would wait for the moment her mother-in-law would go away and she would throw up the food in the big corridor of the house.

However, Gyanada felt that her mother-in-law had been totally averse to the idea of her son Satyendra going away to England to take his ICS examination. After Satyendra, her second son left for the foreign land, she took some jewellery belonging to her mejo bou and gave them to her daughters as their marriage gifts, seething in an unknown rage. Of course, Gyanada did have no regrets about the jewellery, taken from her. But the moment Babamoshai, her father-in-law came to know of this, he became very angry with his wife and sent a diamond neckpiece for Gyanada.

Forever accustomed to living inside the inner quarters of the house, Sarada would find it difficult, rather impossible to accept any changes within the structure of her home. As Gyanada grew up in the later years, her defiance of the norms of that inner sanctum, her free will, and her introduction of modern ways of living inside the home enraged Sarada. Gyanada had understood quite well that her decision to sail in a ship to reach the shores of Bombay, to live with her husband in the alien land for two long years would never be tolerated by her mother-in-law. She also knew it would be more difficult to live with her mother-in-law under the same roof from now on.

It had been an uphill task for her to grant permission to go and live in Bombay, for that matter.

It had been an uphill task for her to grant permission to go and live in Bombay, for that matter. Ever since her husband went away to the city, he was keen to take his wife there, to get her introduced to the free, empowered women of the outside world. It was an era when it It was an era when it wasn’t customary for the women to tag along with their husbands when they ventured to distant places for work or travel. But Satyen, made of different clay, had been reluctant to live far away since the beginning, while his wife remained within the four walls of the Thakur bari. His letters written to his wife during those days bore testimony to this fact. Once, he wrote to her: “You “now, all the incredible progress and state of bliss that we see in the human society here, all its beauty and praiseworthy attributes…at the core of it all, lies the goodness, the bounty of women. I strongly want you to be an unforgettable example for all women in our own society, but remember, it all depends upon your own will.”

Gyanada, a teenager during those days, would read those letters of her husband and silently prepare herself for her journey toward the light. However, it all remained a distant dream as Babamoshai, her father-in-law did not grant her permission after all. Dejected and bruised by his thwarted dream, Satyen settled down in Bombay, his workplace, while his wife started preparing herself in a different way. The girls and women of the house had started taking Bengali lessons from Hemendranath, a brother-in-law of Gyanada, and she joined his little academy along with her sisters-in-law Neepamayee, Sukumari, Swarnakumari and Barnakumari. This would cause the ire of her mother-in-law who would open stop talking to her or punish her by ostracizing her from all the other women in the family. This again would provoke the anger of Maharshi Debendranath, her father-in-law, and hence, when Satyendra appealed to him to send Gyanada to him for the second time, he gave his permission without further delay. This permission proved to be a historic one, opening the doorway to the greater universe for all Bengali women.

… Gyanada also had to bear the brunt of her mother-in-law’s fury and take in all her pent-up bitterness.

However, due to the aftermath of this event, Gyanada also had to bear the brunt of her mother-in-law’s fury, and take in all her pent-up bitterness. Gyanada was a wise soul; she had instinctively understood the psyche of her mother-in-law, shackled by the limitations of patriarchal values, and so, she was not angry. She stooped to offer her pranam to her mother-in-law, knowing very well that she would get a good scolding.

Sarada, seated on the large bedstead, was annoyed as she looked intently at Gyanada’s attire and her bold gait.

“What’s this new way of draping a sari?” She asked.

“Ma, this is the way women wear their saris in Bombay. If you drape it in this way, you can come out and meet people from outside.” Gyanada replied.

“And what have you worn in your body? A jacket like those mem-sahibs?”

Gyanada felt embarrassed at this question. But Satyen talked on her behalf. “Why Ma, don’t you like it? You know, all high-class, sophisticated women in the west drape their saris in this exact way these days. Now our own girls and women will imbibe this style.”

“Stop! It’s enough that you are dressing up your wife as a clown, don’t pull my good-natured girls and brides into this. They will follow exactly what they have followed for all these years; I won’t allow the sanctity of this household to be spoilt!” Sarada blurted.

They were in awe of her style of draping the sari with intricate pleats in the waist area, the anchal attached to her left shoulder…

As the heated discussion between mother and son continued, the women of the household kept listening to it and watching their mejo bou’s attire and get-up with full attention. Her sophisticated frilled jacket, her soft chemise that peeked from her waist where the jacket ended, mesmerised them. They were in awe of her rust-coloured silk sari, the border of which was adorned with fine Parsi embroidery work in black and gold. They were in awe of her style of draping the sari with intricate pleats in the waist area, the anchal attached to her left shoulder with a dainty brooch, in awe of her socks and imported shoes. But some of those women who were traditional to the core silently took the side of Sarada.

Sarada looked at her son and remarked: “I don’t know what you are up to, such ominous acts you indulged in…making your wife sit in an automobile, making her board a ship, uprooting her from her home, her husband’s land and leaving her in an alien land! Can you imagine the humiliation, the criticism we have to face? I alone have to bear the brunt of it all!”

Suddenly, a woman came running all the way from the open courtyard to the big corridor and gave a big, celebratory hug to Gyanada. She was the ubiquitous saleswoman of the Thakur Bari.

“Mejo bouthan! Do you know you created history today? All Bengali women will hail you in pride a hundred years from now!” She screamed in excitement.

“Oh, Malini, when did you arrive?” Gyanada said to the bookseller woman, startled by the sudden call.

Seething in anger, Sarada threw her hand fan at the saleswoman.

Seething in anger, Sarada threw her hand fan at the saleswoman. “Stop your drama and get out of here! History! What an explainer of history we have here! Go away at once!” She screamed.

Satyen came up to his mother and hugged her tight. “Why are you so angry, Ma? It is indeed history, what Gyanada did today. If you would ever step outside of this house, you would see the gait, the personality of Marathi women, and understand how superior they are, compared to our own Bengali women. If only you would see them once, you would realize the concoction of softness and sternness in their persona, which ought to be the ideal for every Bengali woman.”

He noticed a sari-clad young girl seated silently, next to his mother, and shook her braid in jest. It was his younger sister Barnakumari. “Barna, tell me the truth, don’t you want to dress up like your Mejo bouthan (sister-in-law)?

Barnakumari kept mum, and the other girls surrounding her hesitated to speak too, in fear of Sarada. However, after some time, their initial phase of shock and surprise subsided, and they started talking to Gyanada. Their Mejo bouthan had always been the nucleus of their attraction in the household because of her unique personality, and besides, she was social and amiable too and knew how to tempt them towards new attractions.

The bookseller woman held Gyanada’s hand and stood silent, with a glum face.

Only two years back, there was quite an uproar in the Thakur bari centred on their Mejo Bou’s decision to journey to Bombay. The members of the house were brimming with questions, anxieties, and curiosity. What she would wear while on her way, they all had questioned. After a lot of speculation, they ordered an incredible ‘oriental dress’ from a French tailor, custom-made for her. The attire was so complex that Gyanada herself couldn’t manage wearing it, nor could the other women in the family help her with it. Finally, her husband Satyen helped her in the mission.

… Gyanada had realised that in order to attain the liberation of women, it was essential to liberate the attire of women from its shackles of custom.

At that moment, Gyanada realised that in order to attain the liberation of women, it was essential to liberate the attire of women from its shackles of custom. From that time, the idea of draping saris in a fashionable way kept haunting her mind. She had observed the simple, convenient way of draping saris imbibed by the Parsee women in Bombay, and from that, she envisioned the image of the sari-clad Bengali women.

Gyanada had become the emblem of emancipation, an endless source of knowledge to the women of the Thakur bari, trapped within the four walls. They were oscillating between two extremes: their fear of Karta Ma Sarada Devi’s admonishment and their irresistible attraction toward Gyanada. While chatting with Gyanada, they took her to her new bedroom, and Malini, the bookseller women accompanied them. She would check what new books Gyanada brought along.

Sarada looked at them and said: “Look, Satyen, your Babamoshai (father) had already made my life miserable by changing his religion and becoming a Brahmo, now don’t make me suffer again by thrusting your theories of women’s liberation.”

Translator’s Note

The vernacular Bengali literature of my own ethnic lineage that I largely grew up on was a fertile ground for unforgettable stories, and my exploration of metaphorical truths of myriad human experiences through reading such rich literature has expanded my horizons phenomenally. As a sensitive reader exposed to this rich literary world, I was not only intrigued by these classic masterpieces, but day after day, I kept feeling that as a translator, I could act as a cultural bridge, connecting the diverse trajectories of the poetic and fictional worlds of the vernacular authors par excellence and the global readers who want to taste those intriguing poems, stories, narratives.

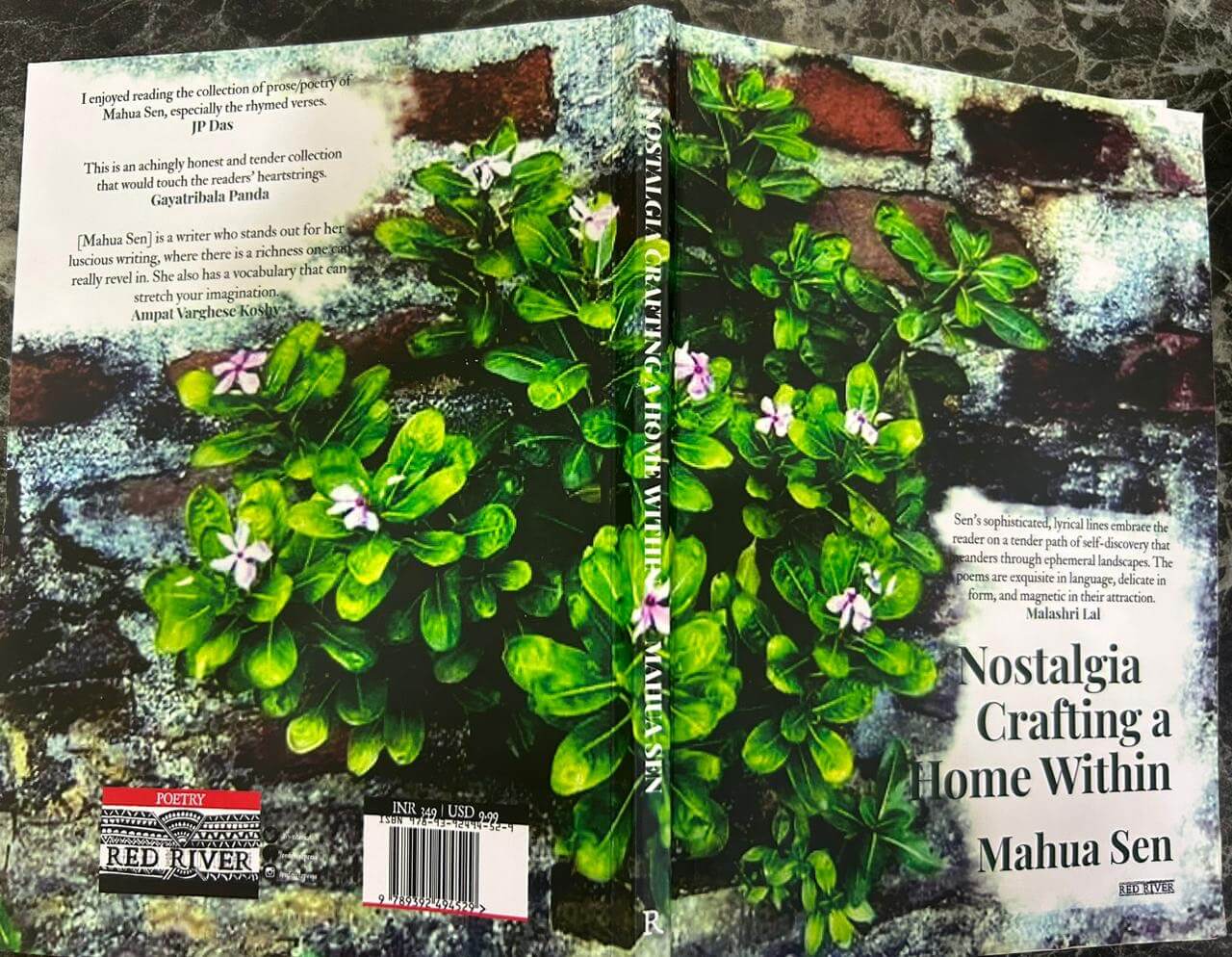

Bengal’s award-winning poet and novelist Mallika Sengupta had published, Kobir Bouthan during the turn of the new millennium (2000), which is a biographical novel based on the lives of the various protagonists belonging to the illustrious Jorasanko Thakur bari, Kolkata, the birthplace of the Nobel laureate of Bengal, Rabindranath Tagore. The women and men within the Thakur bari and their lives have inspired the journeys of many people in Bengal, and the women have especially played pioneering roles in shaping the contours of society, beyond their lifetimes, and these phenomenal journeys form the premise of this book.

The book focuses on the multifaceted history of the illustrious Jorasanko Thakur bari, Kolkata, the birthplace of Nobel laureate Tagore and how the interpersonal relationships between men and women inside that mansion become historically significant in terms of gender and culture studies of the pre-independence era in India and in terms of the development of Tagore’s poetic persona. Through this important translation work, which is a deeply layered narrative, I have tried to unfold the subtle nuances of the socio-political history of Bengal in those times, while retaining the original flavour of the characters and the daily rigmarole of their lives.

Embarking on this journey of the English translation of this avant-garde feminist text has been my honour and delight, inspired by a note sent to me by Subodh Sarkar sir during the pandemic times, giving me permission to translate the novel for global readers. My translation of this classic work will, I believe, enhance the emotional and creative landscape of this beautiful original book, as I hope to convey the fluidity between languages, continents and cultures.

Author’s Bio: Mallika Sengupta (1960–2011) was a radical Bengali poet, feminist, novelist, and academic from Kolkata, India, famously remembered for her “unapologetically political poetry”. She has authored more than 20 books in Bengali, including 14 volumes of poetry and 3 novels (including ‘Kobir Bouthan’), a widely translated poet invited to several international literary festivals. She has also been the poetry editor of Sananda, the largest circulated Bengali fortnightly (edited by Aparna Sen). Along with her husband, the noted poet Subodh Sarkar, she was the founder-editor of Bhashanagar, a culture magazine in Bengali. In addition to teaching, editing and writing, she was actively involved with the cause of gender justice and other social issues.

(To be continued)

Picture design by Anumita Roy, Different Truths

By

By