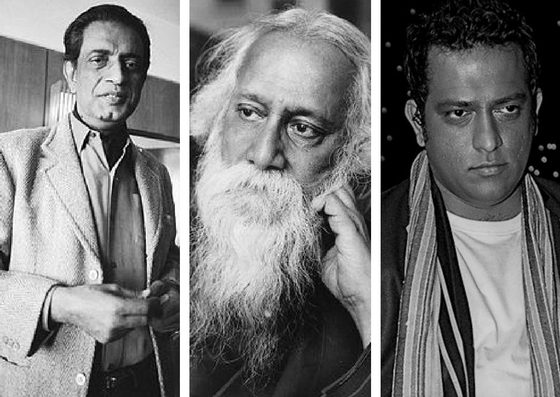

There are many admirers of Satyajit Ray’s film, Charulata (1964), which is often seen as a retelling of the story of Rabindranath Tagore’s own time spent with his elder brother and his wife. To Nilakshi that is not only a reductive interpretation but also sheer belittling of the prodigious talent of Tagore in rendering the twists and turns of human character and emotion. Moreover, there are significant differences or departures from Tagore’s original story Nastanirh (1901) that the logic of film demanded, that Ray incorporated to produce this classic film. This article does not address itself to scholarly readers and critics but the audience, the lovers of the film, who might not have read the novella or even did not watch the recent faithful adaptation by Anurag Basu, in 2015, in his television series (“Stories from Rabindranath Tagore”), she says. A Special Feature that examines a story, a film, and a TV adaptation, exclusively for Different Truths.

There are many admirers of Satyajit Ray’s film Charulata (1964), which is often seen as a retelling of the story of Rabindranath Tagore’s own time spent with his elder brother and his wife. To me, that is not only a reductive interpretation but also sheer belittling of the prodigious talent of Tagore in rendering the twists and turns of human character and emotion. Moreover, there are significant differences or departures from Tagore’s original story Nastanirh (1901) that the logic of film demanded, that Ray incorporated to produce this classic film.

Charulata is a beautiful, artistic, upper-middle-class housewife, lonely in her childless marriage, and  innocent and capricious like a child herself. Sensing that she needs company her busy intellectual, political thinker and press-owner husband Bhupati, gets her brother Umapati and his wife Mandakini, to live with them. He also hosts his cousin Amal to sit for his exams from their house. Charulata needs company: Amal and Manda gave her colourful afternoons. He appreciated her talent, which no one noticed, encouraged her to write and publish, gave her both tough competition and fun through his own writings, and teased her by playfully ganging up against her during card games and other pastimes with his easy friendship with Manda.

innocent and capricious like a child herself. Sensing that she needs company her busy intellectual, political thinker and press-owner husband Bhupati, gets her brother Umapati and his wife Mandakini, to live with them. He also hosts his cousin Amal to sit for his exams from their house. Charulata needs company: Amal and Manda gave her colourful afternoons. He appreciated her talent, which no one noticed, encouraged her to write and publish, gave her both tough competition and fun through his own writings, and teased her by playfully ganging up against her during card games and other pastimes with his easy friendship with Manda.

Yet he soaked her with his need for HER company, HER attention, HER friendship. That’s what mattered most to her – to Charulata, the lonely woman with the eyeglass, immortalised by Ray. She thought she could always have him as her cherished companion, but he had to leave. Charulata is devastated. She is immortalised by Tagore in his story and Ray in his film as an epitome of a woman longing for affection, and diversion, in her otherwise empty life, who is abandoned by both her husband and later his cousin to whom she began to grow so attached.

Thus far, the stories of the novella, its television adaptation, and the film Charulata are similar. It is after Amal leaves that the telling of the stories seems to diverge. Charu’s breakdown sobs seem to alert Bhupati of her grief over Amal’s wedding and his journey to England, in Charulata, the film. Bhupati, her husband, decides to take her to Puri after she wastes away and is found to be depressed. Later, they continue to live, albeit changed by the incident, in the beautiful, but dark, lonely mansion. In Nastanirh the matters are much more nuanced and actually complicated.

Perhaps the most interesting character Tagore has rendered in the story is Bhupati, her husband, who thinks Charu is heartless as he can’t see any visible signs of her missing Amal. He tries to insinuate discussions, Charu remains tight-lipped and disinterested. He involves himself in writing and tries to please her and surprises her by starting to write for her and pretend that it’s only a friend’s work. Charu is merely amused. She encourages him and it seems to Bhupati that his decision to stop the newspaper and spend more time at home really paid off, as he himself was almost feeling like they were a newly married couple discovering each other. Married life became, for the first time, bliss for him.

As Amal never wrote even a line to Charu and she never ceased to expect long letters from him and was wasting away with his indifference, she really found herself floundering. She repeatedly asked Bhupati if Amal wrote any letters to her, and was repeatedly devastated by his seeming rejection of her. She took desperate measures after sending Bhupati away on a day trip to her cousins in Chinsurah. It is only when he learnt that she has secretly sold some of her ornaments for a reply-paid telegram to him in England that Bhupati finally realised that she needed Amal more than he could ever understand.

She too learnt that he had come to know everything, and starts living the life of a lie. Bhupati observed her every move closely. But, here comes the uniqueness of Tagore… Bhupati’s heartbreaks, out of his compassion for his wife. She who has no name to give this feeling, no one to share it with, no words to share, no place to even cry out loud, must, like the typical housewife, continue maintaining her beautiful self and keep house for him. How can she do it? He marvels at her capability to conceal her feelings, and her emotional strength and decides to give her time and space. For any feminist reader, this would be the ideal husband: sensitive, forgiving, accommodating even though it’s not easy.

However, the reality is what Tagore carefully considered: Bhupati needs to find his bliss too, and he decides to leave for Mysore for work, and even when she pleads, he does not want to take her with him. It is not that he wants to punish her but he cannot take the sheer weight of both their emotions anymore. He couldn’t possibly carry the ruins of their broken home, he considers. But, even though he withdraws his hands from her clasp, at their final meeting, he relents after seeing her pale and shattered face. Charulata, sensing the cause of his earlier rejection, decides to stay back alone.

Nastanirh ends with the utter finality of Charu answering Bhupati’s call to join him at Mysore with a “Na, thaak.” (No, let it be.) Such an emotionally charged story ends with two monosyllables.

Stories from Rabindranath Tagore by Anurag Basu follows the plot structure of Nastanirh, showing a lonely Charu sitting outside the mansion in the end, after the goodbyes are done. In one of the finest scenes in black and white cinema, the prolonged play of light and darkness continues in Ray’s Charulata when Bhupati returns home late one night. Charu extends her hand inviting him home, saying “Esho” meaning “come”, but the extended hands, stay poised but yet to meet, in the lonely mansion as the last shots freeze and blur.

Stories from Rabindranath Tagore by Anurag Basu follows the plot structure of Nastanirh, showing a lonely Charu sitting outside the mansion in the end, after the goodbyes are done. In one of the finest scenes in black and white cinema, the prolonged play of light and darkness continues in Ray’s Charulata when Bhupati returns home late one night. Charu extends her hand inviting him home, saying “Esho” meaning “come”, but the extended hands, stay poised but yet to meet, in the lonely mansion as the last shots freeze and blur.

Perhaps to extend the story and show what and how Bhupati felt would not have suited the dynamics of film, or Ray’s more contemporary thought process. Perhaps it’s enough to show the depth of his emotions when he cries alone in the horse carriage, or looks at Charu affectionately as she goes about her duties, or takes her to Puri and watches the sea waves retell their life’s story, as Ray depicts in Charulata. The resolution comes much earlier and is more significantly modern and complicated in the film! How will Charu and Bhupati live with the shadow of the past between them? Will their hands ever meet? Will their souls seek each other once more? Here are stuff and substance for yet another story! Ray’s interpretation leaves the audience spellbound and thinking. Isn’t life all about forgiving, forgetting, moving on? Or not?

Many other questions arise in readers’ or viewers’ minds. What happens when the “other one” comes in between two lives? What would happen to Charu if Bhupati fell in love with someone? Would Charu have to clench her fists and bear it? Would she understand his compulsions? Or would she like to leave? Indeed there could be an entirely new story here again.

Who better to answer than the maestro, the Gurudev? Who else would know what could go on the mind of an educated, middle-aged man’s heart in response to a wife’s love for his cousin? That his response could indeed be sympathy, understanding, rather than anger and hatred? That he would want to leave the scene and let her mourn her loss? Or, to take another story, Chhuti, in which he writes so well about exactly how any boy of thirteen or fourteen feels like a misfit and longs for understanding. Or the famous Streer Pawtro, in which Mrinalini leaves her husband not for any wrong done to her but to a poor young girl, a distant relative.

Who better to answer how he could know and express these emotions, than he himself, Gurudev?

Photos from the Internet

#Gurudev #RabindranathTagore #Nashtanirh #Charalata #Movies #SatyajitRay #AnuragBasu #Dramatisation #ShortStoryOfTagore #TributeToTagore #DifferentTruths

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By