Lopamudra interviews Shuvayu Bhattacharjee about his music career, from childhood tabla lessons to composing and filmmaking, highlighting his diverse influences and industry struggles. An exclusive interview for Different Truths.

“Music is the language of the spirit. It opens the secret of life bringing peace, abolishing strife.”

— Kahlil Gibran

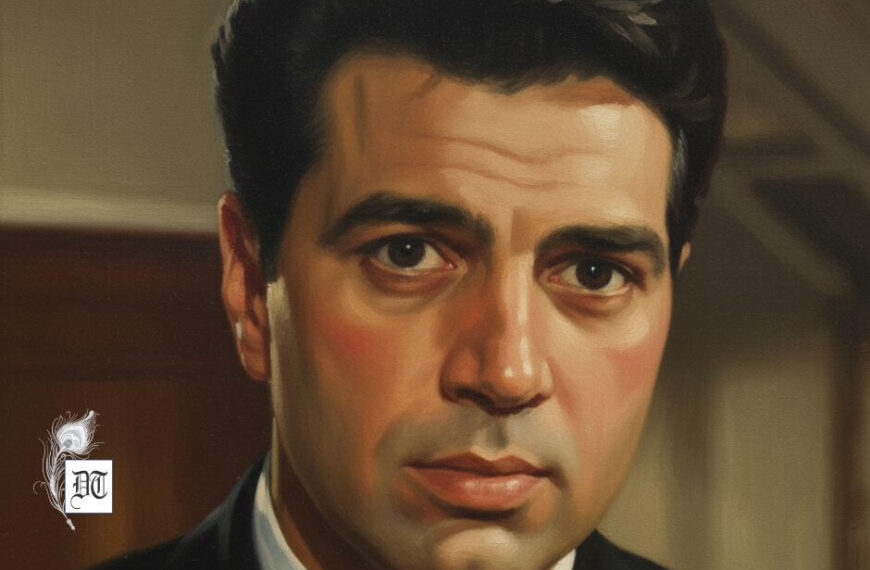

As an individual deeply connected to the soul and essence of music, I stumbled on Shuvayu Bhattacharjee’s music and his deep-rooted love for all creative forms when I met him for the first time in Kolkata on a drizzling August evening some years back through my poet friend Gopa Bhattacharjee, who incidentally is his life partner. The inexplicable passion for life, which unfolded through words, music, and artistry, became our common bond since then, and the rest became history, as we worked together on our poetry film in 2018–2019 and formed a lasting friendship. Years later, in this interview conducted entirely online, I look back at those moments of serendipity, as the singer, composer, and filmmaker from Kolkata, my homeland, shares interesting facets of his creative journey.

Lopamudra Banerjee: Welcome onboard, Shuvayu! We have had a long association together since we started working together on our poetry film ‘Kolkata Cocktail’ (2019), and we will come to it somewhere in this interview. However, let us first begin with your childhood, your musical journey, and your formative years in music and the creative arts. You have come a long way today, starting as an indie short filmmaker, composer, and music director, to today, when you are associated with making music videos for Global Bengal Media and Entertainment. What is the story of your creative journey?

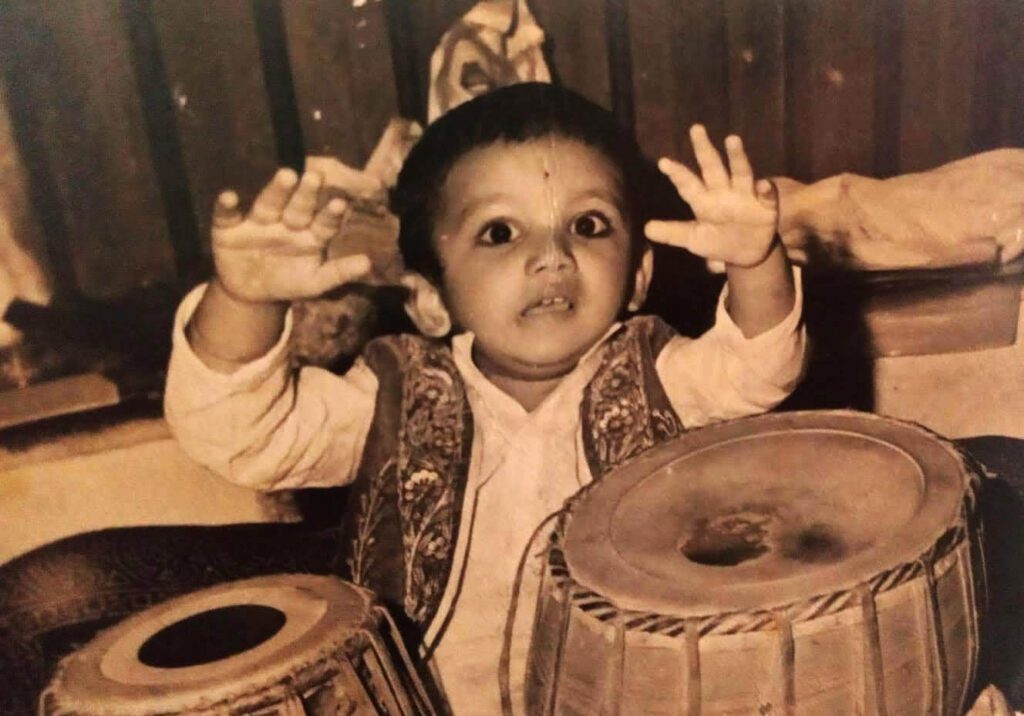

Shuvayu: I was born into a very ordinary family. My father ran a small grill shop, and my mother was a homemaker. My mother used to tell me that at a very young age, I would take a large-mouthed milk tin as a baya and a small-mouthed tin as a duggi and play with them. In my mother’s family, my maternal grandfather, the late Pandit Haribhushan Bose, was a renowned tabla player. My attraction to the table propelled my mother to introduce me to the eminent tabla player Late Babu Hirendranath Ganguly, known as Hirubabu, a famous figure in Bengal, India, and the world, who gave me my first tabla lesson during a Saraswati Puja. However, since I was just three years old, my initial tabla lessons started with my mother’s uncle, the late Ardhendu Ghosh, Hirubabu’s student. My mother called him “Mama,” and I called him “Dadu.” He lived in Santoshpur, next to Jadavpur, in south Kolkata, while we lived in Dum Dum, in north Kolkata. Given the transportation challenges of that time, I had to find a new teacher.

Meanwhile, significant changes occurred in my family. I learned that my father was the eldest son of one of the most prosperous families in our area. He had been disowned for marrying my mother against the family’s wishes. However, after resolving all family matters, we moved into my grandfather’s house—a large mansion with many rooms, where my uncles, aunts, and many others lived. From a one-room house and a kitchen, I found myself in a palace, and also became friends with Junior Kaku, leading to a lifelong bond of master and disciple. Junior Kaku, also known as Babu, was my father’s only paternal aunt’s son and an excellent tabla player, a disciple of renowned tabla player Late Babu Radhakanta Nandi. My youngest aunt learned classical and Nazrulgeeti songs, and they played music all day. I had a great time then. I had a tabla set, including a copper baya, which was rare those days. After teaching me for a while, Junior Kaku, whose good name is Manas Chakraborty, took me to his guru, Radhakanta Nandi Moshai, who lived in a grand house with a huge gate, bougainvillaea bushes, and two cars. I still remember the large ground-floor room of his mansion, and how Master Moshai (that is what I called him) used to sit reclined on a white cushion and takiyas (pillows) like an emperor, and the three large hookahs with a scent of amber tobacco.

I learned from him for three years, receiving much affection, although I’m not sure what I learned. However, when I was very young, just a student in class 5 or 6, the sudden death of my Master Moshai shook me, and I didn’t touch the tabla for a few weeks or a month. One of my mother’s uncles, a renowned classical music critic, Late Binoy Bhushan Bose, took me to Late Pranab Ganguly, the head of the rhythm department at Rabindra Bharati University. Unfortunately, a few days after my classes started, Pranab Dadu passed away. Afterwards, my mother took me to Kumar Da in Baghbazar, Kolkata. Pandit Kumar Bose, at the time a rising star in Bengal, regularly accompanied famous musicians like Pandit Ravi Shankar. His father, Late Bishwanath Bose, was a close friend of my grandfather. Kumar Da called my mother “Bulidi,” by her nickname. I often arrived early before classes and waited on the stairs. Next to the stairs was a room where some students used to learn to sing. Those days, I used to sing Ghulam Ali’s ghazals at home, listening to the tape recorder. One day, while humming on the stairs, a thin, bearded man came out and asked me to sing louder. After I sang, he told my mother to bring me to his singing classes without any fee. Although I didn’t attend regularly, I took some lessons from Acharya Jayanta Bose. He was the one who taught me to break down music into notation and practice slowly, a method I still follow to master any musical phrase. Practising by focusing solely on the notation, without lyrics, strengthened my musical understanding, a technique I

learned from him.

Kumar Da (Pandit Kumar Bose) went on a world tour with Pandit Ravi Shankar, leaving me without a teacher. My mother took me to the legendary Gyan Dadu (Pandit Gyan Prakash Ghosh), who was quite old at the time. After he declined to teach me, my mother took me to the Late Mahadev Bhattacharya, a student of Gyan Dadu, who lived close to our home.

My brief tutelage from Kumar Da, which lasted for about six or seven months, made me realize that I lacked a deeper connection with the tabla’s traditional intricacies, phrases, and grammar, however impressive my table playing was. Kumar Da had started showing me these essential aspects, but my education remained incomplete due to his departure to the US. Under Mahadev Jethu, my education in tabla resumed, focusing on these fundamental elements.

A year later, Kumar Da returned to the country and immediately called me to resume my lessons. However, my mother did not want to pull me away from Mahadev Jethu. Thus, a separation from Kumar Da occurred. Unfortunately, shortly after this, Mahadev Jethu’s only child passed away from cancer. This tragedy turned Mahadev Jethu into a stone; he stopped conducting classes. I asked my mother if I could return to Kumar Da, but perhaps she felt uncomfortable asking Kumar Da again after having declined him once. Consequently, I was left without a teacher once more and practiced by reviewing my old notes.

Once again, Junior (Manas) Kaku came to my rescue. My mother had taken me to Pandit Shyamal Bose, but he was unwell at the time. Junior Kaku, who was then a student of Pandit Gyan Prakash Ghosh, took me to one of his fellow disciples, who was also a student of Shyamal Bose. Sujit Kumar Das, whose nickname was “Makan,” lived in Tala, near Hirubabu’s house. Sujit Da never called me “Shuvayu” but “Shuvo.” In our first meeting, I became a fan of Sujit Da. He was nearly 6 feet 2 inches tall, with a beard that resembled Kumar Da’s, and was equally handsome. In our first meeting, he corrected my tabla posture. I learned from Makan Da for many years. He was not just my teacher but my guru, my true mentor; he taught me tabla, music, philosophy, and how to live through music. He formally inducted me into the Farrukhabad music gharana. Whatever I have learned in classical music is because of Makan Da.

He introduced me to the art of practicing with iron bangles on my wrists and candle practice. In essence, he taught me about the different styles of classical music, the variations of compositions according to different gharanas, and much more through rigorous training. In 2015, he left this world; his departure was much too soon.

Meanwhile, another event was quietly unfolding, but I deliberately kept it to myself. I was learning to sing as well, but I didn’t tell anyone because many people believed that one should focus on mastering a single skill rather than trying to learn two things simultaneously. However, I continued with my singing lessons. My singing guru was the Late Ajay Mukhopadhyay, the brother of the famous Rabindra Sangeet artist Dwijen Mukhopadhyay, a family friend of ours. Unlike his brother, Ajay Dadu was adept in classical music, Nazrul Geeti, and older genres like tappa, dadra, thumri, and choiti, and had learned music from the renowned music director Sachin Dev Burman. After Sachin Dev Burman moved to Mumbai, Dadu became a student of Burman’s guru, Guru Vishmadev Chattopadhyay. Dadu taught my sister and me at home for many years. Later, I also learned from Mukut Chakraborty of Rabindra Bharati University.

When I was in class 7 or 8, there was a musical program in our local area, and a lady we used to call Lal Pisi, Miss Shila Joardar, was trying to teach a few kids Rabindra Sangeet for that event. She was a friend of my father and the sister-in-law of one of my aunts. She used to play sitar, was working at a big company, and was self-reliant. I started learning Rabindra Sangeet from her, though many of my family members did not know about it. She was possibly a disciple of Suchitra Mitra. I used to spend time with Lal Pisi mostly on Saturday or Sunday evenings and learned a lot about Rabindra Sangeet. This continued for about two years. Despite all this happening, I never mentioned to anyone that I was taking singing lessons. None of my school or college friends knew about my singing background. They were often amazed that I could accurately sing semi-classical songs by Manna Dey or ghazals by Ghulam Ali and Mehdi Hassan. Yet, whenever I sang Rabindra Sangeet, I could completely change my accent and approach the songs without any formal training.

Towards the end of my college years, I suddenly began composing music, which opened up a new horizon for me. Some friends formed a musical group, and I joined primarily to compose music. Along with classical music, I started to be interested in Western music due to a creative urge. There was no internet then, so resources were limited. Through a friend, I met guitarist Nanda Da, who introduced me to Salil Chowdhury’s symphonic ideas and chords. I tried to understand how symphonies were composed and their structure. This same friend later introduced me to Carlton Kitto, and I developed a love for jazz. My extensive training and passion for Indian classical music might have helped me easily absorb jazz. I memorized pieces by Lee Ritenour, Chick Corea, Stanley Clarke, Stanley Jordan, Earl Klugh, George Ben’s son etc., note by note.

From jazz, I developed a love for blues, influenced by B.B. King and Eric Clapton, and gradually explored ABBA, Osibisa, the Bee Gees, Michael Jackson, Led Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones, Beatles, Metallica, AC/DC, Bryan Adams, and eventually Latin music and flamenco. I became a lifelong fan of Paco de Lucia. I didn’t just listen to these genres; I delved into their theories. This exploration eventually led me to adopt music as my profession, and I remain immersed in that passion and love for music to this day.

Lopamudra: That is quite a fascinating story about your musical journey from your childhood to your formative years! Now, let us discuss another aspect of your creative journey, filmmaking. Tell our readers about your first stint with Widescreen Films & Music, the YouTube channel where you first dabbled with the craft of short filmmaking. What inspired you to make films in the various genres that you did? What has been your most successful project under the banner of Widescreen till now?

Shuvayu: I have been fond of Western movies since childhood. We had a VCR, and I used to watch films regularly. This had perhaps sparked my interest in filmmaking. In 2012, I directed a short film, “Ki Ashe Jay,” which was shown on a leading TV channel. This success encouraged me to create a few more short films, such as “Bublur Boi” and others.

However, to be honest, I am not satisfied with any of the short film projects I worked on under Widescreen. Most of them had issues such as low budgets, poor lighting, unimpressive framing, and various technical flaws. However, “8 p.m.” attracted a wide audience and received mixed reviews. “Bublur Boi” remains especially close to my heart for very personal reasons.

Lopamudra: What drove you or inspired you to make an unusual short film like ‘Kolkata Cocktail’ with three women poets?

Shuvayu: Firstly, because of Gopa Bhattacharya, I can’t ignore any request from Gopa. Secondly, I am unaware of the novelty of the work, and I am also not sure whether anyone in Kolkata had done this kind of creative work in the genre of poetry film before me. Although I am not fully satisfied with the work I did, it was a good learning experience for me.

Lopamudra: How important has the role of music been in your storytelling, when you have directed such short films? Is there any specific interesting story/anecdote you remember while creating/composing the music for these projects?

Shuvayu: Music is an extremely important element of any film. Even when films were silent, music was still used. However, in almost all the work I have done so far, I have had to intentionally use more music. Critically speaking, this is a shortcoming of my films. The charm of background music lies in its seamless integration with the scene, making it feel completely connected to the film. There is music even in silence, which creates the moment. I wasn’t able to achieve this because I had to use music to cover up the shortcomings in my films’ framing, lighting, acting, etc., leading to excessive use of music, which is not always necessary.

Lopamudra: In your recent music videos, I have witnessed how your tunes/compositions are embedded with Bengal’s folk tradition, infusing the elements of dance, music, and narrative storytelling. What are the unique ethnic perspectives of the region of Bengal that you have mostly focused on, in your recent productions?

Shuvayu: There isn’t much to highlight separately; about 70–80% of my music work remains unpublished. Over the years, I have worked on various projects that never saw the light of day. The main reasons for this are the negligence and lethargy of the producers for whom I did the work. By now, I should have composed music for at least 15 Bengali films and one Hindi film, but due to the same reasons, these projects were either postponed or cancelled altogether. Consequently, I went through a period of deep depression. For any professional artist, the release of his/her craft is crucial because one completed project leads to many more opportunities.

While working for “GBME Channel,” I managed to release a lot of my unpublished work, such as “Buker Bhitor Kande Madhumas” which was created in 2010 for another project, but the project never got released. That being said, I don’t have any particular bias toward a specific genre or style; I love working on all kinds of music. In independent music, situational music is less common, allowing for more creative freedom. On the other hand, situational work has its charm and unique challenges.

Lopamudra: I have listened to many of your musical renditions in recent years and personally feel you have a strong classical flair. Whose songs or compositions had a deep impact on your growing-up years, or were they the usual Rabindrasangeet-Nazrul Islam songs only? Has any composer of our modern era inspired you profoundly?

Shuvayu: It’s difficult to name just one person. Madan Mohan is one of my favourite composers. Sachin Dev Burman, Anil Bagchi, Nachiketa Ghosh, Sudhin Dasgupta, and Salil Chowdhury have greatly influenced me. I am a huge fan of Ilaiyaraaja, the famous music director from the South. In my own Bengal, Satyajit Ray’s simple notations have deeply moved me since my childhood. However, Rahul Dev Burman’s compositions will perhaps always remain closest to my heart.

Lopamudra: Finally, how would you like to identify yourself; as a music director, composer, or poetry filmmaker? Which one do you feel would justify your essence more as a creative person?

Shuvayu: Haha, this is a really interesting question. I compose music, program music, arrange music, play instruments, record, mix, and master music, shoot videos, write scripts, and dialogues, build scenes, do shot division, edit, and design graphics, and I’ve done all these tasks professionally on various projects at different times. But everything started with one fundamental desire: I wanted to be a singer. However, along the way, I’ve faced various circumstances that have challenged me to break myself, adjust, and stretch myself as a creative individual.

I can still sing, albeit not very regularly. Sometimes, I sit alone in my studio and sing, listening to myself, critiquing myself, and sometimes applauding, but perhaps I’ve missed establishing myself as a singer. However, even if I achieve modest recognition as a good composer, I’ll be happy.

Pictures procured by the author

By

By