Candice elucidates that access to the “Word,” be it literature or online content, remains restricted, perpetuating historical inequalities despite perceived progress in diversity, exclusively for Different Truths.

Culture en mass would have us believe the Dream is still open for everyone. Look closer throughout history and it becomes apparent, the Dream was never open for everyone. For each individual who came from coal mines, cotton fields, abject poverty, and rose out of that milieu to the ranks of doctor, scientist, professor, there are statistically far more who remain mired in the circumstance of poverty.

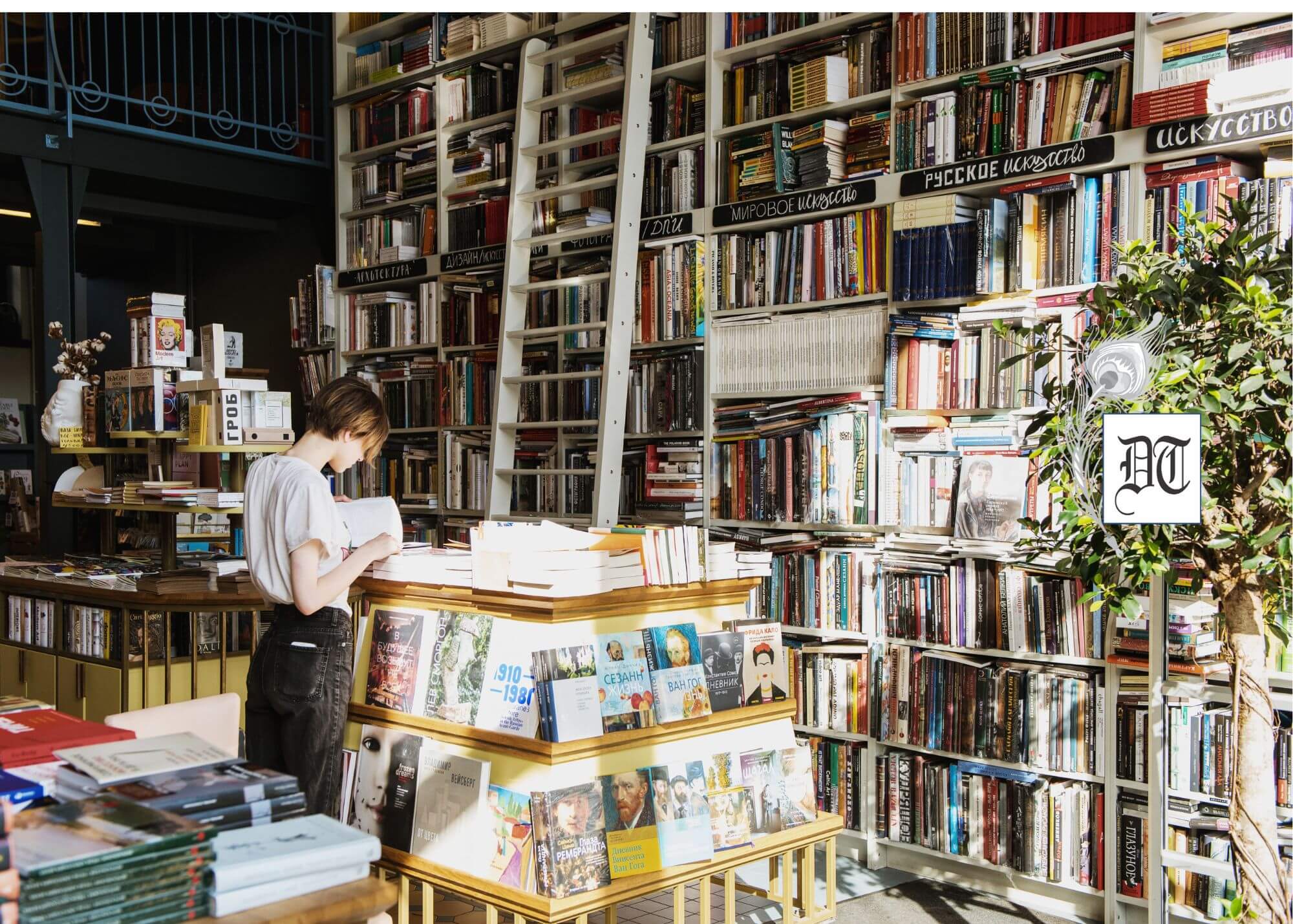

Why this applies to the Word, and by this we mean the social Word, is significant. The Word as it was formerly known, the Word of God, was the greatest social influencer before the advent of social media. Whether God is post-Word or not, today’s Word is the accumulation of information we discover and are influenced by via the Internet and other cultural artifacts.

If that Word is coloured by who is admitted into the sanctum creating the Word, then Houston, we have a problem. It’s always been the case that history is written by the colonizer, and as such, is tainted by their perspective. But we believe that’s past tense and not how it is today, with our plethora of social media and, theoretically, the ability for anyone to write and have it read on a wide platform.

Restricted Access

The title of this is: The Word is Sanctioned by Possibility. Directly because those who have regular unfettered access to possibility are still restricted by classism, economics, gender, country of origin, heritage and thus, possibility. Historically, Jews wrote, it was in their DNA, it seemed to convey things through the written word. But break it down and you will see that only a small percentage of Jews wrote, nearly all men, nearly all the higher echelon wealthier Jews. This is but one of hundreds of examples of misconceptions about who has access. Whether you are Muslim, Catholic or Mormon, you are constrained by the chains wrapped around your faith that dictate who gets access. Catholics were kept away from reading full-translation Bibles. Mormons dictate by class and peerage, who has the most power in the faith. Muslim women are like Jewish women of years ago, denied equal educational opportunities and not encouraged to work. There are exceptions to all of these, but the bottom line remains the same: those who have access are controlled.

If we go with that thought, then. Imagine the Word being a loud speaker with a small opening to speak into that widens to amplify your voice. If the small entryway is clogged with people seeking to be heard, and those with privilege will climb over those without, then who ends up speaking? Has it not always been the case in the literary world that the majority, the vast majority of writers, had some luck or fortune that permitted them to be able to write rather than work two jobs for a total of 60-hour work weeks? How in actuality can ‘normal’ people be at the forefront of the Word, in whatever form, if they need to earn an increasingly hard to make living? Ultimately then, hasn’t access always been to the privileged few?

Today, we talk of equality in broader strokes. I have a good friend high up in Penguin, one of the largest publishing houses in the world. She proudly tells anyone that Penguin has greater diversity in its titles than ever before. This is accurate and true of most of the leading publishers. More women, more people of colour, and more minorities of all walks of life are being published. But do the math. If our population continues to increase exponentially, then one Back woman being published in 1950 would become 1000 Black women being published in 2025. It may falsely seem like greater equality, but it’s simply keeping up with the increase in population. Statistically, it’s still not the norm. This applies to all minorities. Penguin may have a wide catalog of Indian, Pakistani, Māori, Zambian, Moroccan, Japanese and Haitian writers, but statistically, it’s a drop in the ocean when you consider the expanding population.

Tokenism is Fraudulent Representation

What this means is those voices we think we’re representing more haven’t moved the temperature gauge because the majority remain White, Western men. In addition, tokenism is a fraudulent way of representation in general and isn’t sincere in its intention. Given that intention is everything, we’re skating on false ice if the editors and publishers are still the majority paying lip service to the minority and here’s the greatest irony: the minority have never been the minority! Women are 51 percent (give or take), despite their second-class-status. People of colour vastly outnumber the Whites. Those minorities like queer writers, disabled writers, mentally ill writers, survivors and erased writers, they’re even smaller and less represented. Imagine it like a funnel, where the cream is at the top and the rest of us are below, unable to pierce the foam.

Friends often lament my need to say I’m a feminist. They ask me why that matters in this age of equality. Quite simply, they are wrong. There is no equality yet, just as Audre Lorde said, until the tools of the master are dismantled. We are still operating with the same canons and systems, and herein lies the crux of my argument. If we use the same canons and the same systems, we doom emerging generations to inherit the same inequity without even being aware of it. The example I use here is the literary world, as I have worked in it during two separate epochs for approximately 10 years each time.

Publishing in the 90s

Back in the 90s, when I first worked in publishing, it was abundantly clear the only people published were the people who could fiscally afford not to work long hours in another job and could devote the necessary time to their craft of writing. Moreover, those who went to the best schools and universities had immediate access to the inner machinations of the publishing world via those valued networks. If you were outside of this, you were outside, and for every JK Rollings, there were thousands whose petitions to be heard, read, and published were ignored.

One could argue: Tough luck! But there is no luck involved if it’s based upon birthright and skin colour and biology. If you are born the son of an immigrant mother who moved to, say, France at the age of 18 with nothing but the clothes on her back, from an ex-colony. That women might work as hard as it is humanly possible to work and she may do her utmost for her children, but statistically she’s likely to end up in the projects/council housing and statistically she’s unlikely to earn a high wage and thus, her children, entering the inner-city-schools may not receive the best or the most advantaged education, they may have to work early to supplement the families income, they may not be able to afford university even with government assistance, because it comes down to many more factors. Ultimately then when they decide they want to be a writer and they begin to write, aside from not having sufficient time to do so, or financial support, if against all odds they complete a book, how do they go about securing a literary agent or publisher?

Colonisation Robbed Indigenous Peoples

The legacy of colonisation, for example, hasn’t gone away because some weak amends have been made. Colonisation robbed indigenous peoples of their sanctity and right to self-determination. By ‘owning’ the wealth of a country, those colonising countries continue to profit with every advantaged generation that inherited that wealth, just as the colonised will be disadvantaged throughout generations in reverse. Intergenerational inheritance is one of the myriad ways people are socially and economically unequal even before birth. Colonisation caused the playing field to be unfair for generations, and as such, a child of colonisation doesn’t just have racism and sexism to deal with, they have the legacy of that colonization and what was done to their ancestors, putting them in a fragile position that no amount of good intention by former colonists, can undo.

Again, I preface this argument by acknowledging that there are exceptions to every rule. I remember one distinctly. A young woman from Tanzania moved to the UK as a child, excelled in school, received a scholarship to Cambridge, graduated and got an MFA from UEA before writing a best seller. I remember her well. A prepossessed genius with a sharp mind and laser-focused ambition. Despite this, she was the first to admit she was an anomaly, that it was less about sheer talent than luck, chance and her good looks. She didn’t say this to dismiss her talent but to be honest about what it takes, what it always takes, to ‘become’ successful in conventional terms.

For every Tanzanian author who makes it, thousands don’t get the opportunity. Here’s the crux of the argument: Opportunity is access, access to the Word. If the old systems still control that access, then whether they publish Tanzanian authors or White-Anglo-males they’re still in charge of the mouthpiece, and they’re still part of the erasure of the other voices that never make it up to the cream. This quiet oppression may not seem very serious; after all, why does it matter overly what happens in the literary world when so many people don’t even read anymore?

2025: A Fracture in the Publishing World

Fast-forward to 2025, and I can see a fracture in the publishing world due to this lack of reading. What’s happening instead is that publishing is turning into online publishing in the forms of influencers, websites, memes, and videos. It may look different, but in many ways, not much has changed. Those who want to go for the sake of argument, to the American Writers Association that’s being hosted in California this year, aren’t going to be the writers who work on their local military base where they get seven days off a year. They’re not going to be single mothers who can’t afford childcare, let alone a ticket and hotel in California. They’re not going to be immigrants who get lower-paying jobs because that’s the expectation put on immigrants and always has been (and I say this from experience of having immigrated to three separate countries).

Likewise, look at the publishing world and see who the editors still are among the most successful publishers. Watch who knows who and how. Consider the real-life challenge of getting a writer’s agent, especially if you didn’t go to school with the right people or rub shoulders in an MFA program that costs $45k with emerging writers. Yes, there are people of color who are published, but examine the average income bracket of all successful published writers, and you will find the majority, the vast majority, still come from what we consider privilege. These days, getting an MFA is a springboard to publication, but the average costs of MFA’s are prohibitive to most working-class people, let alone the working poor, the single parent, the immigrant, or the disabled or disenfranchised.

Take the story of Jean Michelle Basquiat. Considered to be an indigent artist at one point, it later transpired he was the son of an affluent businessman who knew how to market himself and reinvent himself before coming under the umbrella of Andy Warhol, arguably one of the most influential men of his era. That’s what it took for Basquiat to become famous. Otherwise, his graffiti-like art may have stayed just that, and the likes of Madonna would not be collecting his pieces for thousands today. That said, Basquiat also suffered the cliché of being a token of colour, lauded by his White mentors, which, whilst stiflingly patronising, at least enabled his platform to be heard. There are gradients of inequity, which explains why some Black people in America ask that White people do not attempt to help them by speaking for them, because it echoes the historic mouthpiece of white speaking for black. Good intentions aside, it’s another appropriation.

A Minority of Breakout Voices

What I’m talking about is the artifice of the creative world, how historically and today, those who are privileged or inordinately lucky are likely to be the only winners. The idea that this has changed somehow and become more egalitarian is an illusion. Take the poetry world. Naomi Shihab Nye had a rich husband and played on her ethnic roots to gain traction. Does it mean she was undeserving or without talent? Or is it just an example of quiet privilege still existing? When I examine those who ‘make it’ in publishing today, I see a tiny minority of breakout voices from relative obscurity, and I see a lot of people who have the money and means to attend MFA programs and American Writer Association galas. I see a divide that is so apparent but never discussed or acknowledged between the working-class woman with three kids, who is a superb writer but will never get a book deal because she can’t shmooze with the right ilk. It is that which convinces me nothing has changed, and the veneer of equity is just that, a thin surface illusion.

Another example is the micro-publishing houses that have sprung up, publishing indie writers, including poets and novelists. It may seem on the surface to be an incredible grassroots generative scheme to highlight indie writers, who by their indie status, are a minority in some fashion. Ironically, however, the machinations at the top are repeated below. Indie publishers who succeed are nearly always bought out by the bigger publishers, who then supplant any indie(isms) with their big-business model, in the guise of. If you doubt this, take a look at the history of how many smaller publishers are purchased by the five largest publishers and how their names and identities are deliberately retained, and then ask yourself why.

Micro-Publishers

Those micro-publishers who are genuine in intention may suffer still from the privilege of being able to run a micro-publisher, a highly unprofitable venture. Explaining why so many heads of micro-publishers are middle-to-upper-class and predominantly White. Because again, it takes privilege to even hope to run such a company. You have to have access to income to run something that doesn’t generate (enough) income. Thus, even with the best intention in the world, can you be sure you speak for the disenfranchised? Or are you more than likely going to fall back into your middle-to-upper-class roots and publish your friends? Isn’t this just another form of the nepotism we see at the top where the creams at?

My Black sisters tell me I’m still Black even if I don’t look Black because I’m half-Black. I don’t ‘look’ gay, according to shallow cliches of what gays look like. But I’m aware my privilege exists in passing, and that’s not to be discounted. Race isn’t biologically movable, yet often in history race has been moved. Jews who didn’t ‘look’ Jewish, able to escape Nazi’s; Black people who could ‘pass’ doing so, women pretending to be male to get certain jobs, and so it goes on. The point is that when you look at what you are, you can’t escape prejudice. This is why many black people want to publish with visibly black-owned publishers, they want to SEE people like them, not just become a token in a White-machine. But if more white people still have the means to run publishing companies than Black people, this inequity isn’t going to be solved until we see the purpose of fiscal support for the Black and minority-owned businesses to ensure people are published by people they resemble. Just like it was once okay for an actor to ‘act’ a gay or trans role, we’re asking that real gay and trans people are now cast. It’s about authenticity and not just playing a part but lived experience of what it entails to be a person of color or gay or trans or Other.

Immigrants and Minority

And what of ambition? How many times do we hear that immigrants often turn against new immigrants when they settle in a country? Is it not human nature to reject a minority, even as you were one, perhaps because you were, as a means of rejecting what you were and advancing to the next level? Are all humans this way? Of course not, but are enough that we see clear trends of this occurring, where formerly oppressed groups exhibit similar behaviors as they gain economic advantage? Take that example and apply it to publishing. Imagine a person who may have come from a disadvantage, but they’re becoming successful. Are they going to bring other disadvantaged people with them and stay true to their roots or succumb to their new peer pressure? If they do the latter, can you blame them, when we all know how short our time in the sun, if we get it, is.

What’s my point? The title of this is When the Word is Sanctioned by Possibility. Too often, working in publishing, I have seen good-intentioned people overlook how many are sanctioned by possibility and, as a result, witnessed how the Word isn’t free isn’t untainted by the same privileges that cause inequality and inequality to persist worldwide. I can argue that Capitalism is one major factor in this occurrence because as long as we consider profit over people, we will never have a free world, and those who should be heard will not be. I also argue that if we are in a hurry to proclaim that feminism isn’t needed because women are equal, and then trickle that thought down to racism, classism, ableism, and other prejudices that deeply impact people’s lives, we’re buying into the Dream, and the Dream doesn’t exist.

Generational Nepotism

For every child of a cotton picker who becomes a doctor, there are many more who continue and perpetuate, through no fault of their own, the cycle of poverty and lack of access. When we talk of lack of access, we talk about an insidious erasure or closed door to multiple lived experiences in favour of those at the top. Privilege is privilege, and it cannot speak for those of us who haven’t ever had access to a slice of the pie. It isn’t communal, and whilst we may feel we are being heard, it’s an illusion of how we could be heard; we are tightly controlled and bound up in the same generational nepotism that has always existed.

When I worked on an anthology called The Kali Project, my co-editor and I received quite a lot of push-back from Indian women who felt that by asking for Indian writers in English, we were missing out on a vast group of oppressed and erased Indian writers. Shamefully, we hadn’t considered that, in our enthusiasm for the project, it hadn’t occurred to us how many wouldn’t have access due to not owning a computer, being able to write in English or having reliable internet. In that situation the argument became, how can we reach those women? In truth, publishing from America we were not able to reach them. It was the downside to the project and a teaching lesson for us both, in understanding that even a small privilege, like living in the West, having literacy and being bilingual, is still a privilege that leaves many people out. I still don’t know what the answer to that conundrum is, to truly find the authentic voices of all Indian women, not just the affluent or privileged. But being pushed back on helped us understand that those considerations must always be part of a wider discussion before embarking on any project, no matter how well-meaning its intention is. We’re talking about being aware of the bigger picture and the necessary ways we might avoid furthering erasure rather than dismantling it.

Minority Voice

I’m always so glad when I see a minority voice allowed a place at the table. I champion those voices. But I’m also acutely aware that as long as they are tokenistic by the permission of those who always sit at the table, then their power is fleeting, if at all. Real change comes when we dismantle the old systems, and to do that, we need to break them apart. The publishing world may be dying and reinventing itself, but the Word will always exist, and we need it to speak for us, not dictate to us what we should be thinking. Otherwise, we’re no better off than those denied access to literacy, blindly following the middle-ages-priest. I see the temptation to publish those you know, but unintentionally, you keep your circles small and parochial, and you stop forcing access for everyone when you get comfortable and familiar. Change only comes when we get uncomfortable and challenge our assumptions and privilege and lack of knowledge of how others experience life. That’s when we are in our rawest state, able to hear what it is like for the majority, and we can ask them: What do you want us to change? Let us hear what you have to say. Not in translation or our words, but in yours.

Picture design by Anumita Roy

By

By

By

By