Ruchira critiques eight short stories of Tagore, in the Special Issue, exclusively for Different Truths.

Once upon a time, there was a little girl named Mini who lived in a spacious house in one of the numerous by-lanes of Kolkata. By a quirk of fate, she struck up an affectionate friendship with an Afghan peddler (vendor) of dry fruits. But their amity was short-lived. The Afghan (Kabuliwala) was sentenced to a prison term on charges of homicide. Years passed by … on Mini’s wedding day the Kabuliwala re-appeared. In a poignant tone, he divulged to the father of the bride that he had been drawn to Mini because she reminded him of his own daughter back home in the wilderness of Afghanistan. Needless to say, Kabuliwala and Mini are humane characters immortalised by Tagore in his short story by the same name.

On a personal note, in an educated, middle-class Bengali family like ours, smitten by Tagorephilia, we grew up reading or listening to similar short stories – compiled under the title Galpaguchchha – authored by the Bard of Jorasanko Thakurbari (or Santiniketan if you please). Our lives were peopled by innumerable larger-than-life characters created by Tagore. We laughed and cried with them. They appeared in our dreams, shaped our emotions, and moulded our approach towards life and the world.

Tagore was a master storyteller. He culled real-life experiences of people around him, as well as his own, marinated them in his own emotions and subsequently painted them in myriads of hues. And the result was sheer magic!

The bulk of Tagore’s characters are ordinary humble, folks, their lives tumultuous with toil and struggle; yet their hearts are full of love compassion and sentiments. And most important of all, in their heart of hearts they dare to nurture dreams: of fulfillment in love, (not necessarily carnal love) a home & family, success, happiness and so forth… Sadly enough, many times, their nondescript lives are snuffed out…and they depart from this world unwept, unsung.

For instance, the story, Shubha, revolves around a hapless mute young girl. Ironically she bears the name Shubhasini (one of talented speech). As she grows up, her parents push her into matrimony. Once her handicap is discovered, her husband dumps her to marry a healthy unimpaired woman. And Shubha is left to bemoan her fate.

The story titled Post Master portrays unfathomable bonds of affection that is forged between the  postmaster of an obscure country post office and Rattan, an orphan teenager, who doubles up as his cook and housekeeper. Once when he falls ill, Rattan nurses him back to health. Later, when the postmaster decides to leave the village for good, Rattan pleads with him to take him along. His refusal leaves him shattered.

postmaster of an obscure country post office and Rattan, an orphan teenager, who doubles up as his cook and housekeeper. Once when he falls ill, Rattan nurses him back to health. Later, when the postmaster decides to leave the village for good, Rattan pleads with him to take him along. His refusal leaves him shattered.

Equally poignant is the story Malyadaan (wedlock/exchange of garlands). Kudani (foundling) a young orphan girl is adopted by a childless woman Potol and her bureaucrat husband. When her cousin Jatin, a medical graduate, comes to stay in the house, Potol tries her hand at match-making as she is terribly fond of the poor mite and wants to place her in safe hands. Owing to long spells of starvation and poverty – before she came into Potol’s loving custody – Kudani falls ill and Jatin treats her. Out of sheer gratitude mingled with affection, Kudani begins to take abundant care of Jatin’s daily needs, comforts et al. Stifled by Kudani’s unwarranted attention coupled with Potol’s constant pranks, Jatin runs away from home. Kudani is stunned. A few days later she too disappears. Dramatically, Jatin locates Kudani in a hospital where he is on an assignment. He brings the girl home and takes good care of her. Ultimately when Jatin learns that Kudani’s disease is terminal, he is deeply saddened; his feelings are mellowed. On an impulse, the visibly upset doctor exchanges garlands with the dying girl. She breathes  her last –complacent that her love is acknowledged!

her last –complacent that her love is acknowledged!

Samapti (The Finale) is a slightly comic though the largely romantic story of a college graduate Apurbo, who is fascinated by, and ends up marrying a little village girl Mrinmoyee. Even after marriage Mrinmoyee refuses to give up her tomboyish ways, much to the chagrin of her husband and mother-in-law. A series of emotional upsurges and misunderstandings follow. When Apurbo returns to his college hostel Mrinmoyee suffers pangs of separation. In this manner, her persona gets transformed. After a hiatus, when Apurbo returns home unannounced, he finds himself in the loving arms of his wife, and all is well.

In the heart-wrenching tale Dena Paona (Debit and Credit) Tagore lampoons the malaise of dowry system which was rampant in his times and in his social circles. A poor girl Nirupama gets married to a bureaucrat hailing from an affluent family. The youth defies his father who raises a hue and cry at the wedding venue demanding a hefty dowry. Since her father is unable to pay stipulated amount even after the wedding (as promised) her in-laws ill-treat her, and even starve her, day in and day out. Her husband, who is posted in another town has no inkling whatsoever of her miserable plight. She is even banned from visiting her parental home. Her desperate father tries to raise funds to redeem his pledge, fervently hoping, they would allow her to visit her parents. But each time, he gets nothing but humiliation and insults. Unable to bear her father’s sorrow the girl forbids him to grovel before her ruthless relatives. A few days later, Nirupama succumbs to mental agony, exhaustion and prolonged malnutrition. Paradoxically, her husband’s family celebrates her funeral with great pomp and show as befits their social status. Wait, here is more. They negotiate another match for their son. This time with a rider: cash first, wedding afterwards!

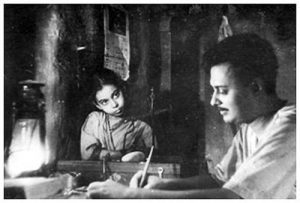

One must invariably mention the much acclaimed Nashtanir (The Broken Nest), which was made into a film Charulata by the legendary Satyajit Ray. The story narrates how a lonely bored childless housewife  hailing from an affluent family stifles her aspirations. Her husband’s effusive young cousin Amal brings a whiff of fresh air into her cloistered, monotonous existence. Since they have a narrow age difference and possess similar literary sensibility, a bond of understanding and camaraderie is fostered. Deeply motivated by Amal, Charu begins contributing articles to newspapers. Her transformation stuns her husband Bhupati, arousing his suspicion. Amal too realises Charu’s welter of emotions but fails to reciprocate. Charu and Bhupati drift apart. Amal marries a suitable girl and travels to England for higher education. Bhupati fervently attempts to come back to Charu but alas there is a yawning abyss between them. Though pertaining to a bygone era, Charu’s life is essentially the tragedy of Indian matrimonial relationships – where scores of women continue in loveless marriages – to escape social scandals and ignominy.

hailing from an affluent family stifles her aspirations. Her husband’s effusive young cousin Amal brings a whiff of fresh air into her cloistered, monotonous existence. Since they have a narrow age difference and possess similar literary sensibility, a bond of understanding and camaraderie is fostered. Deeply motivated by Amal, Charu begins contributing articles to newspapers. Her transformation stuns her husband Bhupati, arousing his suspicion. Amal too realises Charu’s welter of emotions but fails to reciprocate. Charu and Bhupati drift apart. Amal marries a suitable girl and travels to England for higher education. Bhupati fervently attempts to come back to Charu but alas there is a yawning abyss between them. Though pertaining to a bygone era, Charu’s life is essentially the tragedy of Indian matrimonial relationships – where scores of women continue in loveless marriages – to escape social scandals and ignominy.

While winding up, I wish to refer to a soul-stirring story Bicharak (The Judge). When Khiroda a woman of easy virtue, kills her infant son – after her paramour disappears, leaving them penniless and hungry – Justice Mohit Dutta, who is assigned the case sentences her to death. She accepts the verdict stoically. Days before her execution she kicks up a row with the guards who confiscated her valuable ring. When Dutta inspects the ring he is electrified! The spectre of his past grips him…. Years ago, Dutta used to be a lascivious, young man. He had been attracted to a youthful widow named Hemshashi. Calling himself Binodchandra he had struck up an acquaintance with her. Over the promise of marriage, he had gifted her a gold ring with his name etched on it. Subsequently, betrayed and deserted by Binodchandra, the hapless Hemshashi had sunk into the quagmire of a sinful existence. To sum up, Khiroda was Hemshashi of yore while Dutta was Binodchandra! By a quirk of fate, the predator had earned the right to sit in judgment over a helpless woman, whose life he had ruined. Or had he really?

Photos from the Internet

#ShortStoriesByRabindranath #Tagore #Bicharak #Nashtanir #DenaPaona #Samapti #Malyadaan #PostMaster #Shubha #Kabuliwala #TributeToTagore #DifferentTruths

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

Beautifully penned. Really loved reading the article on Rabindranath Tagore by Ruchira Adhikary Ghosh. There is a lovely flow to it which takes you back to your childhood memories. Kudos to the writer.