During the yearlong Satyajit Ray’s birth centenary, beginning on May 2, 2021 to 2022, Nachiketa pays a tribute to the legendary filmmaker, who was at the crossroads of the eastern and western sensibilities. Influence of Tagore and Shantiniketan was palpable in him. An exclusive for Different Truths.

“Though he’s very young still, he’s the Father of Indian Cinema.”

— Jean Renoir on Ray, 1967

Great Awards like the Bharat Ratna, Honorary Oscar (for lifetime achievement), Legion d’ Honor (the highest civilian award in France) and the Kurosawa Award (for lifetime achievement as a film director), were conferred upon Satyajit Ray along with a series of Filmfare festival award.

They (Tagore and Ray) were the last Renaissance men in their respective fields.

“… a person who has not watched a Ray movie is like one not knowing the sun and the moon,” said Kurosawa, one of the greatest film directors. Tagore and Ray both were appreciated abroad and in India because their works were in Bengali and later translated and transliterated into English. They were the last Renaissance men in their respective fields. Both inspired several Indian generations as a poet of poets and ‘director’s director’.

If the context is at the national level, Tagore was recognised for Geetanjali and the Nobel Prize and Ray remained famous for Pather Panchali. Both were presidential institutionally. Ray graduated from Tagore’s Shantiniketan. He never studied film studies from any institute, having a little bit apprenticeship in an advertisement agency.

Ray stated, “My father and grandfather never held jobs. Grandfather Upendra Kishore was a true Renaissance man, who wrote, painted, played the violin, and composed songs. He was a pioneer in half-tone block making and founded a printing press, which soon established itself as the finest in the country. He died in 1915 at the age of fifty-two, six years before I was born. He had sent his eldest son, Sukumar, my father, to England to study printing technology. Father stood first in the final examination at the Manchester School of Printing Technology. He returned home, while grandfather was still alive, got married, and joined his father’s business.1 was born, in 1921, the year that father was taken ill with what was then an incurable tropical disease called kala-azar. He was in and out of bed for two-and-a-half years, looking after the press and contributing poems, stories and illustrations to Sandesh, a children’s magazine which my grandfather founded, when he was comparatively well. After father’s death, at the age of thirty-six, the press carried on for three years. Thereafter, the business changed hands and we had to leave our spacious residence in North Calcutta.” (My Years with Apu by Satyjit Roy).

Shantiniketan, Tagore and Ray

The philosophy of Rabindranath Tagore had a deep impact on Satyajit Ray. He worked on five films based on Tagore literature. Shantiniketan groomed him as visual artist regarding sketch, painting, drawing. His artistic contribution was approved by people off late. His musical fusion is a legacy of Tagore. Ray’s way of observing the society, religion, politics, human life, his way of seeing art, nature, science, beauty, listening to music and nature were unique. It is said that his processing of idea was nearer Tagore. But the philosophy was his own. His documentary on Rabindranath, in 1961, at centenary level was a genius production from which one might spot the impact of Tagore on Ray’s mind. This film states the contribution of the last renaissance person, who has left for us heritage of arts, culture, science and ideas or ideals.

Ray was unwilling to join Shantiniketan initially. But on second thoughts he opted for it in accordance with his mother’s wish.

Ray was unwilling to join Shantiniketan initially. But on second thoughts he opted for it in accordance with his mother’s wish. And Tagore had several times requested Satyajit’s mother to send her son to his university. Ray and Tagore were different in many regards. Ray was fond of urban life, western music, but the affinity between them had the deepest roots. He protested the unwanted eclipse, by the West, on Tagore.

Speaking of Tagore, Ray said, “As a poet, dramatist, novelist, short story writer, essayist, painter, song composer, philosopher and educationists Tagore is obviously more versatile than Shakespeare. But why compare? With indifferent translations Tagore will never be understood in the West as he is in Bengal. As a Bengali I know that as a composer of songs, he has no equal, not even in the West – and I know Schubert and Hugo Wolf; as a poet, he shows incredible facility, range and development; some of his short stories are among the best ever written; his essays show an amazing clarity of thought and breadth of vision; in his novels he tackled some major themes and created some memorable characters; as a painter starting at the age of nearly seventy, he remains among the most original and interesting India has produced.” (Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye, by Andrew Robinson).

Shantiniketan had a direct influence on Ray.

Shantiniketan had a direct influence on Ray. A liberal young German-Jewish refugee Alex Aronson, and an ex-student of F. R. Leavis at Cambridge, who trained him. A contemporary art student, who later became art historian, Prithwish Neogy, and the art teachers Nandalal Bose of Kala Bhaban and Binode Bihari Mukherjee, the renowned painter, these four made him newer. (Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye, by Andrew Robinson).

Why did he leave Shantiniketan without completing his studies?

Ray candidly admitted in the Calcutta lecture, on his life and work, he delivered in 1982: “My relationship with Shantiniketan was an ambivalent one. As one born and bred in Calcutta, I loved to mingle with the crowd on Chowronghee, to hunt for bargains in the teeming profusion of second-hand books on the pavements of College Street, to explore the grimy depths of Chor Bazaar for symphonies at throwaway prices, to relax in the coolness of a cinema, and lose myself in the make-believe world of Hollywood. All this I missed in Shantiniketan, which was a world apart. It was a world of vast open spaces, vaulted over with a dustless sky, that on a clear night showed the constellations as no city sky could ever do. The same sky, on a clear day, could summon up in moments an awesome invasion of billowing darkness that seemed to engulf the entire universe. And there was the Khoyai, rimmed with the serried ranks of tal trees, and the [river] Kopai, snaking its way through its rough-hewn undulations. If Shantiniketan did nothing else, it induced contemplation, and a sense of wonder, in the most prosaic and earthbound of minds. In the two and a half years, I had time to think, and time to realise that, almost without my being aware of it, the place had opened windows for me. More than anything else, it had brought me an awareness of our tradition, which I knew would serve as a foundation for any branch of art that I wished to pursue.” (Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye, by Andrew Robinson).

Ray’s Views on Films

What was Ray’s views on our films?

“It is easy to tell the world that film production in India is quantitatively second only to Hollywood; for that is a statistical fact. But can the same be said of its quality? Why are our films not shown abroad? Is it solely because India offers a potential market for her own products? Perhaps, the symbolism employed is too obscure for foreigners? Or are we just plain ashamed of our films? To anyone familiar with the relative standards of the best foreign and Indian films, the answers must come easily. Let us face the truth. There has yet been no Indian film, which could be acclaimed on all counts. Where other countries have achieved, we have only attempted and that too not always with honesty, so that even our best films have to be accepted with the gently apologetic proviso that it is ‘after all an Indian film’. No doubt this lack of maturity can be attributed to several factors.” (Our Films, Their Films by Satyajit Ray)

The Trilogy depicted the lore of the winning spirit of the human being against odds.

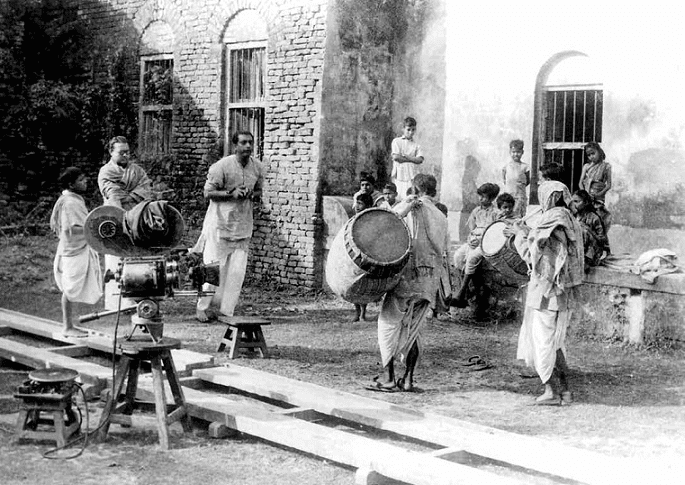

The creation of Apu Trilogy (Pather Panchali, 1955, Aparajito, 1956, and Apur Sansar, 1959) is best known where Apu, the rural boy, youth and matured interacted with outer worldly life experiencing pain and pleasure throughout his life, made Ray internationally acclaimed. The Trilogy depicted lore of winning spirit of the human being against odds. From this theme to another theme, he continued experimenting with all branches of cinematography. Apart from themes like village life, he worked on city or metro life, corporate life, the leftist and nationalistic movement, complexities of family life, famine, musical, thriller stories, conflicts within a family, life of stardom personality with all insecurities, societal superstitions, reduced princely life of colonial India, crisis of modern civilisation including satire, adventures, documentary films and children’s films. Although failed appreciators blamed him on selling poverty to western audience.

The Berlin Festival awarded him much in life for Pather Panchali, Aparajito, Mahanagar (1963), Charulata (1964), Nayak (1966) and Ashani Sanket (1973). Venice awarded him Golden Lion (1982) for Seemabodhha and Aparajito. Winner of 36 times National Film Awards in India, he was conferred with Dadasaheb Phalke Award and the Bharat Ratna. The film on great Bengal famine (Asani Sanket) was not on poverty or hunger rather glorification of the spirit of mother nature. Political voices of Charulata amidst the relationship issue of man and woman, the banality of religious fundamentalism in Sadgati, criticisms of despotic rule in Hirak Rajar Dese, corruption and injustices of contemporary society in Jana Aranya. Devi and Ganasatru depict superstitions and blind religious beliefs, Sakha Prasakha was screened oncorporate corruption, Shatranj ke Khilari indicates the entry of colonials to fill worthlessness of princely states.

His women characters are vibrant and resilient.

…Akira Kurosawa said of it: “I can never forget the excitement in my mind after seeing it…”

Some two decades after the first release of Pather Panchali, Akira Kurosawa said of it: “I can never forget the excitement in my mind after seeing it. I have had several more opportunities to see the film since then and each time I feel more overwhelmed. It is the kind of cinema that flows with the serenity and nobility of a big river. People are born, live out their lives, and then accept their deaths. Without the least effort and without any sudden jerks, Ray paints his picture, but its effect on the audience is to stir up deep passions. How does he achieve this? There is nothing irrelevant or haphazard in his cinematographic technique. In that lies the secret of its excellence.”

Talking of Ray’s observation on Westerner films, he said, “In the West, the cinema has seen some clearly marked periods of revolution, in the course of which certain norms developed and conventions solidified. Occasionally, the discovery of a major new trend — such as neo-realism in the forties — or a new school of film making — such as the Japanese in the fifties — has led to some critical rethinking, but on the whole the larger truths have survived. Even New Wave did not wholly change the face of the cinema. It only enlarged its vocabulary and dislodged some hallowed bricks from the edifice of film grammar. To most films now made in Europe and elsewhere, the norms still apply. It is only in the case of an occasional highly personal work that the critic has to take refuge in total subjectivity. What I consider a far greater revolution has taken place on the level of content. This is a phenomenon of the sixties and is described by the term permissiveness…. There is no doubt that permissiveness in the cinema is of major sociological significance as a reflection of the changing mores of Western society; but to justify it as some higher form of artistic truth is as ridiculous as the simulated intercourse indulged in by unclothed performers in film after film after permissive film.” (Our Films, Their Films by Satyajit Ray).

A legacy of Bengal renaissance and schooling of Tagore’s school of spirituality probably made him a poet of the screen.

Filmmaking to him was writing screenplays and lyrics, sketches of shot sequences, composing music, musical fusion, direction and critical technological usages like light, sound, and camera. Being a director, he worked with great musicians, such as Ali Akbar, Ravi Sankar, Vilayat Khan using eastern and western musical schooling. A legacy of Bengal renaissance and schooling of Tagore’s school of spirituality probably made him a poet of the screen.

Versatile Ray was a successful writer, authoring dozens of stories for non-adult groups. Versatility was his heritage. Satyajit wrote, “My grandfather (Upendra Kishore) was a rare combination of East and West. He played the pakhwaj as well as the violin; wrote devotional songs, while carrying out research on printing methods; viewed the stars through a telescope from his own roof; wrote old legends and folktales anew for children in his inimitably lucid and graceful style and illustrated them in oils, watercolors, and pen-and-ink, using truly European techniques. His skill and versatility as an illustrator remain unmatched by any Indian.” He was successful editor of the famous children’s magazine Sandesh. Scholars opine that he was an artist well known for his sketches.

Ray did not understand his grandfather in his teens, neither was he completely known to the filmmaker.

Ray did not understand his grandfather in his teens, neither was he completely known to the filmmaker. To quote of American filmmaker Martin Scorsese, ‘In the relatively short history of cinema, Satyajit Ray is one of the names that we all need to know, whose films we all need to see. And to revisit, as I do pretty frequently.’ Cinema is a medium for creative expression he was successful in introducing innovative cinematic ideas to communicate hidden statements on the complexities of life aesthetically, while the mainstream relied on melodramatic theatricality of romantic tales.

Andrew Robinson wrote, “Actually Ray is not, as we know. He has taken very little from Indian cinema, true, but his debt to Bengali and Indian culture – as well as to the West – is prodigious, and Charulata is one of the films that demonstrates this most fully – if one approaches it knowing what to look for. Ray can fairly be described as an exemplar of Tagore’s belief that ‘a sign of greatness in great geniuses is their enormous capacity for borrowing, very often without their knowing it; they have unlimited credit in the world market of cultures.’ This may make knowledgeable criticism of his work a tough proposition, as I am the first to admit, but it is also why his films will last when those of some other admired directors are forgotten.”

The contribution of Satyajit Ray in films, is simply his Indianness, as Ananda Coomaraswamy wrote in The Dance of Shiva about Indianness, “What her great humiliation would be to substitute or to have substituted for this own character (svabhava) a cosmopolitan veneer, for then indeed she must come before the world empty-handed.” In person and performance, he had European energy and Asiatic calmness. The legacy he left behind is to be cherished and nurtured.

References

- Andrew Robinson, Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye: The Biography of a Master Film-Maker,

1989 - Satyajit Ray, Our Films, Their Films,1976

- Satyajit Ray, My Years with Apu, 1994

- Andrew Robinson, The Apu Trilogy Satyajit Ray and the Making of an Epic, 2010

Visual by Different Truths

By

By

By

By

By

By