Kolkata breathes life. In its many shades and hues, its agonies and ecstasies, it is the identity of a Kolkataphile, Anindita. Here, in a personal account, she pays tribute to the City of Joy. Born and cradled in Kolkata’s lap, this is the city of many memories, of love and heartbreaks. She would like to return to it again and again from a distant land, where she is.

The city which gave me birth, made me what I am bears an old world charm. I cannot think of my existence without Kolkata. It is my identity, it is the poetry I write, it is the pain I live and it is the song I sing. My love, my protest, my success, my failure, my emotions, my excitements – everything is wrenched with my own city.

The City of Joy has an appeal of its own. The oldest metropolis in India, Calcutta sets up sharp contrasts with other urban centres of India – be it New Delhi, Mumbai or Bangalore. Calcutta is a city that loves to hold on to the past, the history which consists of old spatial and historical dimensions rather than an important node of national political economy, and history, memory and identity are the city’s most trusted tools against flux and change. Calcutta makes for shifting perspectives.

The city of Kalikata or Calcutta has emerged through a very long history that spans over five or six centuries. The poet Bipradas Piplai’s Manasa Vijaya, written in 1495, alludes to a place called “Kalikatah”. The same name also appears a century later, in 1596, in Abul Fazl’s Ain-i-Akbari. The first mention of the name of the place Calcutta was probably in 1688, in a letter to Job Charnok by two East India Company servants from Dhaka’. In the late 17th century, Kolkata comprised of three little hamlets clustered in Bengal. The growth of the city was closely integrated with the proliferation of the enterprises of the East India Company. It was turned into a port-city and remained the capital of the British Raj until 1911. The early notes and images of the city are largely documents of the colonial forces, and are predominantly ethnographic images of the ‘natives’ and their cultures, which are represented through the “colonial gaze”. However, such images transformed radically in the 19th century, as the English educated Bengali middle class strived for freedom and selfhood.

The modern metropolis of Calcutta, finds a happy coexistence of high rises as well as heritage structures and regal old buildings. The Chowringhee road runs like the central nervous system connecting the North of the city to the South. There exists a sharp divide between the essential culture of North and south Kolkata. While the north Kolkata exudes an old world aura of traditional and aristocratic Bengalis who yielded immense power during the early nineteenth century, the southern part of the city is noted for its jazzy newness. Those from North Calcutta consider themselves the guardians of the last bastion of culture, a Bengali hegemonic order that safeguards its culture and refinement. The North Kolkata is known for its famous sweet shops and telebhajas, addas on the street corners, while the south Kolkata is marked by malls, lakes, avenues, over bridges and high rises.

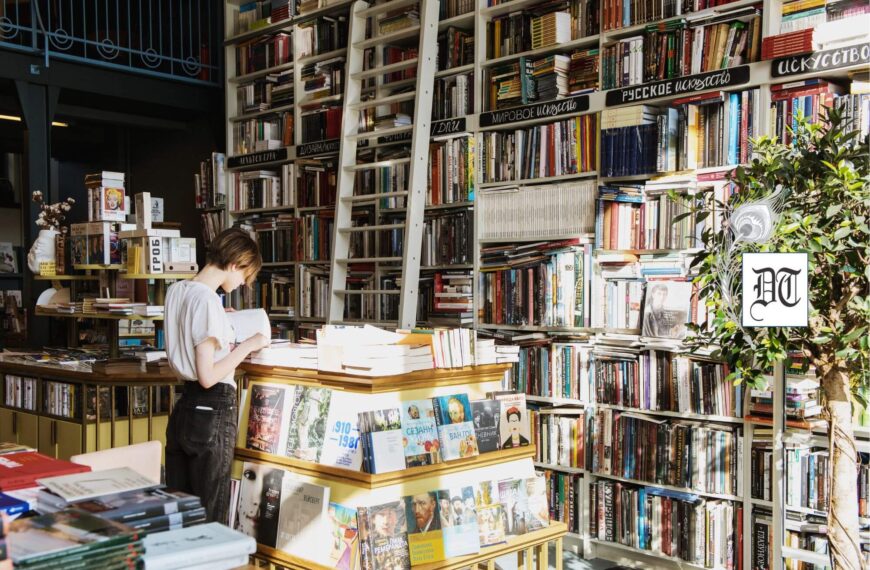

The City of Joy has become home to many Marwaris, who have found their life and living here itself. At the heart of the city lies Park Street that exudes a cosmopolitan charm. The city has expanded its horizons in the east with two new spaces having found their existence in the city’s landscape, one being Salt Lake and the other being Rajarhat New Town. But, still it’s the old and familiar smells of New Market, College Street and Gariahat that one associates with Kolkata. It is the core of the city that shall never grow old, despite the changes that have come over in the urban geography of the city.

It is only in this city that one can find the old rickety rickshaw puller and tram lines crisscrossing the city and plying on the same busy road, thereby creating a traffic congestion, which constitutes a part and parcel of everyday urban existence. Almost as a part of the colonial hangover Calcuttans know their football just as well as the British. It is said that football and politics is there in the blood of every Bengali, they follow the fate of their two football teams with an avid interest and sheer fanaticism. The rivalry between the two teams Mohun Bagan and East Bengal has its roots in the deeper cultural divide. Mohun Bagan team is generally supported by the original residents of West Bengal, while East Bengal refers to the refugees from Bangladesh, who came after partition to find their home in the city. The fanaticism reaches its extreme during derby matches and the divide is symbolically represented through two different kinds of fish, for fish constitutes an integral aspect of Bengali culture and cuisine. East Bengal is represented by Hilsa, while the giant lobsters stand for Mohun Bagan, and on the day of the derby match the market price goes up and down according to the match results.

A Bengali loves his poetry, enjoys his food, and takes pride in his politics and cultural heritage. Food is inseparable from Bengali culture for in very few places across the world one can find an assortment of everything from sweet, sour, tangy, spicy to bitter taste served at one go. Along with new restaurants with bright neon lights of Park Streets, there exist eateries in North Kolkata with hundred years of history engraved in their walls. Bengali cuisine has received worldwide popularity and the almost forgotten and secret recipes of mothers’ and grandmothers’ kitchens have found their places in restaurants to such an extent that even non-Bengalis have started appreciating and savouring them.

The city like every other city has its own life, melody and music, stories and pains, hidden within its familiar sounds and smells, the crumpling and dilapidated heritage architecture, the breakdown of joint family structures engendering nuclear families and leaving one with a sense of alienation and loneliness, old age and claustrophobic existences in two roomed flats, with children settled abroad. Add to this the haste, hurry and everyday rush of life in cabs and metros, and the perpetual wait for homecoming on the other, cosy spaces, traffic snarls, beggars and vendors, busy hustle of street life, bargaining women, children returning from school, muddy puddles and water logging during monsoons and window shoppers. The inhabitants of the city, who have found home and shelter on the pavement, platforms and roads are some of the daily images that constitute the urban life of Kolkata.

Along with the reality of poverty and political anxiety that resides in the interstices of the city, there are the images of hope and consolation that runs like the Ganga, adjacent to the metropolis. As if one dip into the water of the Ganga would purge one clean of the muck of everyday life.

An aesthetically sophisticated presentation of the city life is seen in the imagery of despair in Jibanananda Das’ poems, whose visual sensibility constantly prowls the city, especially at night when it is deserted, exhausted, when the crowds have disappeared, when the city gives up, in a sense its vast, dark despairing truth. The poetic discourse of the city is a dark one, where lives are unfulfilled and people go through the subtle defilement of their everyday existence. There are images of loss, darkness and pain, but they are often relieved by hope and optimism. The metropolitan world is one of necessarily mixed feeling in which values are being continuously overturned, the highest beauty found in the utmost lowly surroundings; and the flaneur that moves restlessly through the alleys and boulevards, represents the only possibility for authentic experience.

The metropolis constitutes a frame or theatrical stage for activity. The buildings of the city, the office cubicles, bars, clubs and pubs, domestic kitchen space, complexes, high rises and its interior setting in particular, form casings for action in which, or on which, human subjects leave ‘traces’, signs of their passing, markers or clues to their mode of existence. The black fairy atop Victoria Memorial has seen many winters and summers go by, she has been a silent witness to many love stories fold and unfold and wept silently at souls who that died before their prime. The Howrah Bridge stands as a hallmark of the city that lives with its heart and loves with its soul.

The city is integrated into my existence.

It acts as both my stimulant and irritant. It has been my first home and it is where I would like to die and cremated, if I had a choice. It is where I have fallen in love and felt the pain of heartbreak. The city has seen me cry tears of joy, as I carried my baby home. It is here, where I have seen my loved ones being taken away wrapped in garlands and flowers. I have sat in silence on the banks of Ganga, in Dakshnineswar, and watched the starlit sky with fascinated eyes. I have walked through the by-lanes of the city and listened to its heartbeat and heard its untold stories.

Whenever I see my city through the window seat, as the flight takes off, I feel a sense of loss, and pain. The Kolkataphile in me rejoices on every homecoming. The smell that fills the air during Durga Puja, the images of Sidur-khela (married women smear vermilion on each other) and embrace on Bijaya Dashami, the sounds of conch shells as the evening comes down, and the tinkling of my mother’s bangles in the kitchen, as she cooks for us, makes me fall in love with life every day.

Being far from my home, I know I shall always love my city, and despite its thousand problems, I shall come back to it with a fond heart and loving warmth that shall never grow old!

Pix from Author

By

By

By

By

By

By