Reading Time: 5 minutes

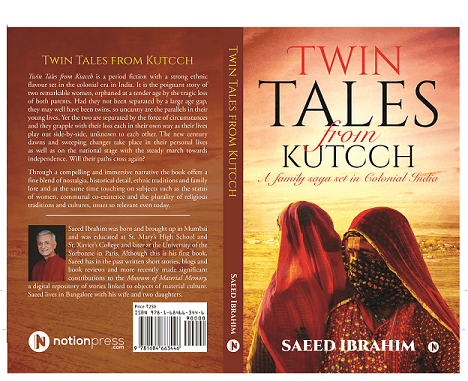

Twin Tales of the Kutch is a captivating historical fiction novel exploring the lives of two intertwined women in India, showcasing love, loss, and resilience. A book review by Azam, exclusively for Different Truths.

“Life affirming.” C. Stammers.

“Nostalgia. History. Humour. And romance. And a story that stays with you.” Dan Bharucha.

Vitalising twinning in the period saga, Twin Tales of the Kutcch, Saeed Ibrahim deftly overlaps haracters, places, and situations within he novel’s hall of tactically placed mirrors in perfect sync. It may raise a whiff of William Faulkner’s twinning in Flages in the Dust/Sartoris, but remains unique to Saeed Ibrahim’s polished craft.

He wipes clean the last traces of vernix caseosa to orchestrate pairing with alarming clarity. Birth and death immutably signify life, death and the cycle of fertility in the human quest for everlasting life, entwined in Twin Tales of the Kutcch.

Thus, it is, that beyond the perpetuity of ISBNs and LCC numbers, the narrative strength of Twin Tales and its dualistic worldview will remain an eternal testament to Saeed Ibrahim’s dexterity of spiritual thought brooding over a pair of family bequests. As he explains: “The inspiration for writing this book was derived from two heirlooms that had come down in my family from the late 19th century. The first was a bone China tea service, which was from my great grandfather on my paternal side, and the second was a framed citation or sanad presented by the Viceroy of India to my great grandfather on my maternal side. The more I contemplated these two relics from my family’s past, the more determined I was to find out about their origins and, more importantly, about the personalities of the two individuals from whom we had inherited these items, their lives and the times in which they lived. As my research progressed, the characters from the past seemed to come alive and I became convinced more than ever that I had to tell their story, if nothing else to leave a legacy for my children.”

And Saeed Ibrahim’s legacy also reaches the fortunate who navigate the binaries of joy and tragedy embroidering Twin Tales of the Kutcch.

Destiny overrides the separation of time, space and circumstances to join the two Aishas. Known to each other, yet unaware of each other’s life, their stories weave the same pattern. Each Aisha faces challenges with the same courage and aplomb. Unknown to either, fate leads them to the end game.

Yet, Wayne C. Booth’s Implied Readers can safely cuddle by a roaring fire with a cup in hand, savouring the privileged information gleaned from both lives isolated from each other, while tingling with excitement at what-happens-next until the ending. That the Aishas are blissfully unaware of an Implied Reader hovering over their lives, percolates reading pleasure.

Ibrahim Saeed further enlightens: “My book tells the story of my great grandparents from both sides of my family who lived in the erstwhile princely state of Kutcch in the latter part of the nineteenth century. I have tried to capture the nostalgia of that period, an era of steam ship travel, horse-drawn carriages and gas-lit street lamps.

“Alongside the narrative, which covers the time frame from the closing years of the nineteenth century to the period just before independence, I have included historical details to provide a suitable setting and backdrop to the story, coupled with vignettes of the lives and times of the Kutcchi Memon community – their origins, their customs and traditions, clothing and food habits.

“There are several other understated themes that are covered in the book, such as the migration and resettlement of diaspora, public health, the status of women, communal harmony and the plurality of religious and cultural traditions, parallels for which can be drawn in our own times, because these issues are so relevant even today.”

Based on real events, the time-frame is not a device but an integral part of this biographical fiction set in India during the first half of the nineteenth century. The effects of the Indian Renaissance fathered by Raja Ram Mohan Roy and the aftermath of the First World War ushered in a period when the biggest jewel started squirming in the exhausted British crown, in itself untenable due to near-bankruptcy, and the brink of a social revolution. The situation in India was best understood by ‘Kim’ Kimball O’Hara, the Lama, horse trader Mahbub Ali, and Kim’s handler, the British spymaster, Colonel Creighton.

Events preempted by the hastiness of the 1947 Partitions had been racing to 1957, the bicentennial of the 1757 Battle of Plassey the British had won on the toss of treachery, to wrest control of India. It’s first anniversary in 1857, had had been celebrated by a revolt of the Indian army now called a War of Independence led in the field by only warrant officers.

The British had neither stomach nor troops to face another revolt, this time commanded by Sandhurst and Dehradun military academies’ alumni leading the 2.5 million battle-hardened Second World War veterans who had defeated Germans, Italians and Japanese — the largest professional army in history.

In the aftermath of 1857, generations of the elite had returned from higher studies in the UK, inspired to gain independence in order to create Britain’s democratic model for India’s volatile diversity.

The 1942 Beveridge Report desperately sought to forestall socio-political chaos in the British Isles by promising to tackle the five giants of Want, Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness, subsequently leading to Bevan’s White Paper and the National Health Service. That left no scope for social reforms in India for which the priority was to cop out before 1957 could spark another military revolt.

So, stoking communal divisions to continue the Great Game as the United States’ international gofer, Great Britain artfully quit India, setting the stage for Indians to kill each other with industrial age hockey sticks and bladed weapons of antiquity. With an estimated death count of one million, India and Pakistan came into existence and have continued the bloodletting over realty.

Twin Tales of the Kutcchis a microcosmic, counterfactual gem of the period preceding the 1947 Partition of India and Pakistan — a ray of sanity, overriding divisions and separation, to rebuke the macrocosmic killing fields and trains of death the British left as their

legacy. Not to speak of 88% illiteracy, 32 years life expectancy and no health service or public education worth the name, except for fee-paying, lucrative schools for the elite to ensure unequal opportunity.

Twin Tales of the Kutcch brings love, family and humanity to the fore in subliminal criticism of the brutal independence of India.

Bangalore-based Saeed Ibrahim, is also the author of The Missing Tile and Other Stories, illustrated by Danesh Barucha. Born and brought up in Mumbai, Saeed is an alumnus of St. Xavier’s College and Sorbonne University, Paris, who also teaches French at the Institute of Foreign Language and Culture.

His professional career in marketing, advertising, airline and travel industries spans India, the UK and France. His refined cultural interests range from theatre, music, films and impressionist paintings, to travel photography, heritage, and heirlooms, garnishing his narratives. From his writing desk, he contributes book reviews, travel literature and essays which start as notes on a writing pad and then graduate to his computer.

When he’s not doting on his granddaughter or playing with his dog, he indulges in his cultural interests and a fitness routine.

Cover image sourced by the author