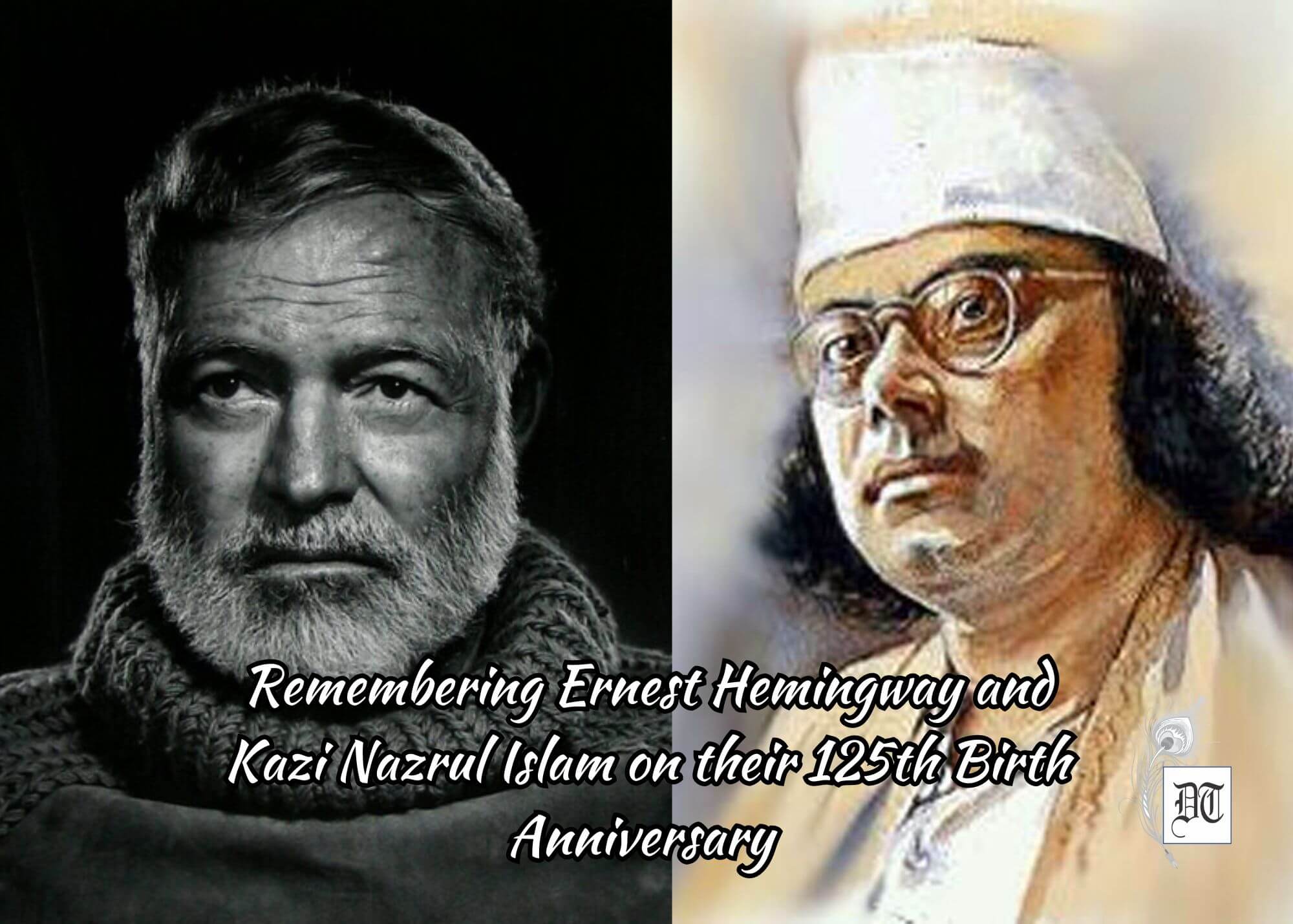

Sanjukta examines the lives and works of 20th-century literary figures Ernest Hemingway and Kazi Nazrul Islam, highlighting their commitment to social justice and anti-war sentiments, exclusively for Different Truths.

On July 21st, 2024, this year, the world celebrated the 125th birth anniversary of Ernest Hemingway, one of America’s most celebrated writers. Events were held at his birthplace in Oak Park, Illinois, as well as in Key West, Florida, Idaho, Spain, France, and more specifically Cuba, where Hemingway had spent the latter half of his writing career. There is a common perception among some Hemingway critics and biographers that Hemingway could be described as much a Cuban as an American.

This perception was further strengthened when he donated his 23-carat Nobel gold medal to the Cuban people. He placed it in the custody of the Catholic Church for display in a sanctuary in the small mining town of El Cobre, outside Santiago de Cuba. That was in 1954, when in his Nobel acceptance speech on December 10, 1954, Hemingway said, “Writing, at its best, is a lonely life. Organisations for writers palliate the writer’s loneliness but I doubt if they improve his writing. He grows in public stature as he sheds his loneliness, and often his work deteriorates. For he does his work alone, and if he is a good enough writer, he must face eternity, or the lack of it, each day.”

Interestingly, this year the Hemingway aficionados assembled in Key West, Florida, to celebrate this extraordinary American writer’s 125th birth anniversary. The announcement for the celebration stated, ‘Ernest Hemingway look-alikes, writers, anglers, and fans of the late author’s work are to gather in Key West Tuesday through Sunday, July 16-21, 2024, for the annual Hemingway Days celebration. The festival honours the legacy of the American literary giant who lived and wrote on the island for most of the 1930s…the festival events include the wacky “Running of the Bulls,” a presentation on 1930s Key West, a commemoration of the 125th anniversary of Ernest’s July 21 birth, a museum exhibit of rare Hemingway memorabilia, a three-day marlin tournament recalling his passion for deep-sea angling, literary readings, a street fair celebrating the island’s lively spirit, and a 5km run and paddleboard race that salute Hemingway’s sporting interests. The Lorian Hemingway Short Story Competition is run in conjunction with the festival by Ernest’s author granddaughter.

Hemingway, an Activist-Writer

Noticeably, although his close Communist friends Cuban Fidel Castro, President of Cuba, and Argentinian revolutionary Che Guevara had visited India, America’s towering literary figure, Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961), did not set foot on Indian soil. Yet predominantly during the 60s, 70s, and 80s, in Indian universities, Hemingway was iconised as an activist-writer, who was not shy of raising those tough questions about the ruthless agenda of funding wars by Western powers and the establishment turning blind, deaf and dumb about the thousands who are killed in wars, without being in any way involved in the politics of war and its ancillary power and profit.

It was trendy then to refer to Hemingway as ‘Papa’, as we did when we were students at the Presidency College in the seventies. While in his 1926 novel Farewell to Arms, the protagonist Fredric Henry makes a separate peace” by deserting the army, in For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940), the protagonist Robert Jordan dies in guerilla combat as he volunteers to support the Spanish guerilla fighters in their fight against the fascist regime of General Franco. These two war novels By Hemingway introduced the counter-discourse, challenging the hegemonic discourse about male militarism, that glamorised hyper-masculinity, power, and jingoism.

What would have been Hemingway’s response to our contemporary troubled times if he lived today? In the 21st century, the killing of innocent people, that is, the mass murder that wars perpetrate, is elided by the state, by telling it slant. So now if one or many die due to participation or even non-participation in a war, such deaths are no longer referred to as casualties of war, the irony embedded in the signifier ‘casualties’ is unmistakable. In the 21st century, civilian deaths in wars are dismissed as ‘collateral damage’, an even more convenient abstract evasive phrase. So, in A Farewell to Arms, Fredric Henry introspects, “Abstract words such as glory, honour, courage, or hallow were obscene beside the concrete names of villages, the numbers of roads, the names of rivers, the numbers of regiments, and the dates.”

Hemingway and Nazrul

Quite remarkably, Hemingway’s direct contemporary, colonial Bengal’s rebel poet Kazi Nazrul Islam (24th May 1899–29th August 1976), joined the British military as a havildar during the First World War. After the war, he returned to Bengal and Calcutta and started his remarkable career as a poet, fiction writer, journalist, and songwriter, drawing heavily on Communist ideology. Both Nazrul and Hemingway lived through the two world wars, and both enlisted in the First World War. While Nazrul enlisted in the British army during the First World War, Hemingway joined the war in Europe, volunteering to serve in Italy as an ambulance driver with the American Red Cross.

Significantly, in the 21st century, while Kazi Nazrul Islam seems to be remembered more often for his trail-blazing poem Bidrohi (Rebel poet), Hemingway’s fame as a novelist is often confined to the phenomenal narrative, The Old Man and the Sea. This is a reductionist approach and perhaps a strategy to limit the impact of the deeply political resistance literature that both these writers had created.

Though Kazi Nazrul Islam and Ernest Hemingway were both born in 1899, Nazrul had in all probability read some of the novels of Hemingway, such as A Farewell to Arms and For Whom the Bell Tolls, Hemingway, I am almost sure, was not aware of Nazrul’s existence. This simple yet crucial fact brings us to the questions raised by intersectionality studies, defining how location and class can either empower or marginalize. Yet both the American and the Bengali writers were truly waging a common war against violent and oppressive regimes.

Hemingway, as a war correspondent, exposed unequivocally the atrocities unleashed by the fascist rule of General Franco in Spain. Hemingway also participated in the two world wars as referred to earlier, and in each case, his commentaries were the unerring voice of the counter-public. In For Whom the Bell Tolls, Robert Jordan explains why he voluntarily joined the Spanish guerillas to fight the fascist regime, “You fought that summer and that fall for all the poor in the world against all tyranny, for all the things you believed in and for the new world you had been educated into.”

Nazrul Protested British Rule

It must be noticed among his contemporary writers that it was Nazrul who protested uninhibitedly against British rule in India and served a jail term for a so-called seditious poem he had written. Due to the British government’s ban on many of Nazrul’s writings, English translations of his powerful Bengali patriotic poems were not then available. Understandably, English translations of Nazrul’s writings did not reach Europe or the USA, any time before India’s independence from British rule in 1947.

One wonders how Nazrul and Hemingway would have reacted to this violent world environment if they were living now. Ironically, universal humanism, ethics, social justice, inclusiveness and respect for diversity are merely concepts that public intellectuals and research scholars engage in on the ground, while blatant defiance of all principles of ethics seems to have been legitimised and institutionalized by the global powers.

The Human Cost of Conflict

If they were living now, could Hemingway and Nazrul remain unperturbed as and when news reached them of people being bombed, thousands of children being massacred, and homes, hospitals, and schools being destroyed in Ukraine and Gaza? In his anti-fascist novel For Whom the Bell Tolls, Ernest Hemingway used John Donne’s passage as an epigraph, warning readers about the self-destructive world and asserting that vested interests are solely to blame for fostering a diabolical environment of ruthless violence: “No man is an island, entire of itself;…any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind; And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; It tolls for thee.”

Significantly, while he was incarcerated in the British administered Presidency jail in Calcutta, in 1923, in his deposition as a political prisoner, Ernest Hemingway’s contemporary, his Bengali writer-comrade Kazi Nazrul Islam, whose 125th birth anniversary is being celebrated worldwide too along with that of Ernest Hemingway, wrote, “I have no fear, no sorrow, for the Lord is with me. My unfinished work will be completed by others. Truth’s desperation to reveal itself cannot be restrained. The comet in my hand will now become the flaming torch in the hand of the Lord, to scorch injustice and oppression.”

War and Geopolitics

In the 21st century, we notice that instead of becoming obsolete, wars still play a dominant role in geopolitics, as loss of lives and property are considered inevitable, as these losses fulfil the overt and covert agenda of securing economic and political power and profit. It is the crucial need of the hour to re-engage in the reading of these two phenomenal writers who were direct contemporaries, Ernest Hemingway of the USA and Kazi Nazrul Islam of India and Bangladesh, who still stand tall as they were able to transcend the narrow dimensions of nationalism, race, religion and class. The world needs to step out of the embrace of dementia and acknowledge that the caveats against violence and oppression created in the powerful writings of both Ernest Hemingway and Kazi Nazrul Islam should be read and re-read to generate resistance and resilience in our collective consciousness against oppression and violence.

Picture from painting

By

By