Ruchira looks back at 2022 for a cultural round-up of the Bengali Associations in Delhi-NCR. Tagore’s presence was palpable – an exclusive report for Different Truths.

After a two-year lull owing to the pandemic, which virtually transformed the contour of the globe, things began limping back to normalcy in the departing year. Gradually, this became palpable in all spheres of life — business, commerce, education, lifestyle, and entertainment. Cinema halls reopened; fashion extravaganzas, theatre, and stage shows — encompassing dance and music of varied genres — burst into life.

This year, Bengali’ culture vultures’ (read Tagore aficionados) residing in Delhi-NCR were treated to multiple delightful, flamboyant evenings soaked in Rabindra Sangeet. Quite natural since Tagore happens to be the most conspicuous icon for Bengalis. Numerous cultural groups and societies in the zone girded their loins to dish up exciting programmes. Coinciding with Tagore’s 161st birthday, the lovely Shirin Soraiya flew down from Kolkata to regale the audience at a programme the Probhash Kalyani Preeti Trust organised. Shirin sang ditties like “Aaji subho dine,” “Kigabo ami ki shunabo,“ “Chorono dhorite,” et al.

This year, Bengali’ culture vultures’… in Delhi-NCR were treated to multiple delightful, flamboyant evenings…

A few weeks later, the Bengal Association — the capital’s oldest fountainhead of Bengali culture — celebrated Tagore’s death anniversary via marvellous recitations of Tagore’s poems befitting the occasion. Soulful renderings followed this by Srabani Nag, a familiar face in the metropolis’s music circles. Dhayjeno more sakal bhalobasha, Jiban Jokhon Shukaye Jae, and many others were among her songs.

Still later, Gurugram-based musical troupe Ananda Dhara (lit., “fountainhead of bliss”) came up with a scintillating presentation titled Pancha Kanya. The theme revolves around five outstanding women characters culled from Tagore’s poetry, lyrics, and ballet (Nritya Natya). The concept is pertinent to the contemporary social milieu. Yet there is a lasting humane quality palpable throughout. The opening section featured Giribala (short story Manbhonjon), a rich, bored, childless housewife; she is neglected and deserted by her husband Gopinath, who is clandestinely involved with a stage actress named Lobongo. Giribala works quietly to reclaim her identity and avenge her humiliation, eventually rising to the status of sensational celebrity. Gopinath is petrified!

The second female character is Gandhari, from the epic poem Gandharir Abedan.

The second female character is Gandhari, from the epic poem Gandharir Abedan. Although she had volunteered to remain sightless for life to express solidarity with her husband, Dhritarashtra, on a moral plane, she is not blind to his follies. In this dramatic piece, surcharged with emotions, she plaintively appeals to him to admonish the vile Duryodhana, who appears jubilant because the Pandavas—having been trumped in the crucial game of dice—are on the verge of departing for the forest. She also pleads with him to dissuade the siblings from going into exile. Hers is the pitiful cry of a woman and mother figure who adores her nephews as much as her children.

The third is Mrinal, the protagonist of Streer Potro. During a pilgrimage-cum-holiday in Puri along with her in-laws, she writes to her husband, spelling out clearly and emphatically that after living as a doormat for years, she is now determined to live life on her terms. Hence, she wouldn’t return to her marital home after the trip.

The fourth character is Chitrangada, princess of Manipur, who, despite being born a woman, was reared as a male and endowed with masculine attributes, e.g., valour, chivalry, and marksmanship. A chance encounter with Arjuna, the third Pandava, ignites her femininity and passions. On his part, the Pandava is impressed by her persona, albeit in a male guise. After a virtual roller coaster ride of emotions on both sides, she finally reveals her true self—latent feminism concealed by a rugged exterior—to Arjuna; he reconciles with her duality.

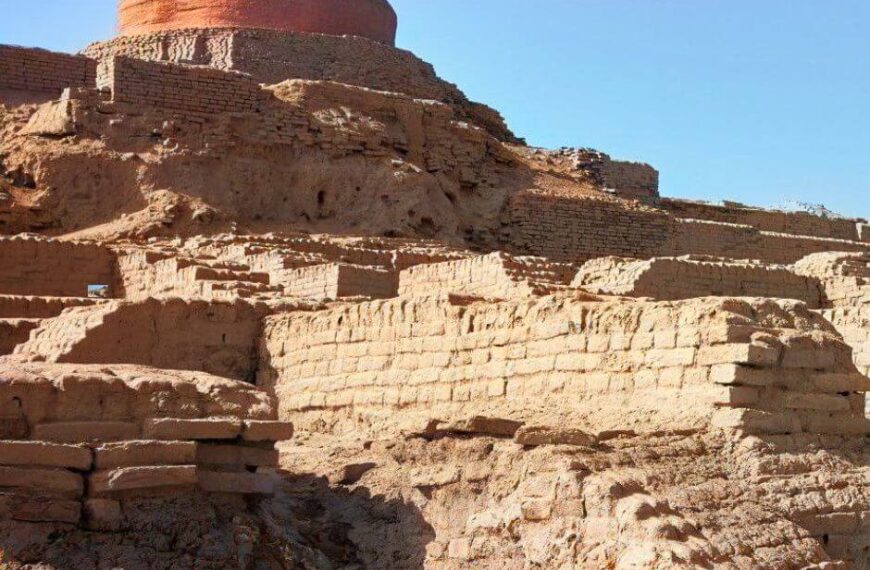

Lastly, one witnessed the poignant tale of Srimati (the poem Pujarini and the ballet NotirPuja), a maid in the royal household of King Ajatshatru, who had vowed to stamp out Buddhism from his dominion. A devout Buddhist, she was slain for daring to offer prayers at a decrepit stupa lo the palace precincts.

The entire presentation— theme, concept, and visualisation- is the brainchild of Mahua Pramanik, who has made Gurugram her home for two decades. She was born in Kolkata and studied under the late Sh. Sushil Mullick, a student of the legendary George Da (Debabrata Biswas). She also had a stint with AIR Kolkata. Being born and raised in an unorthodox Brahmo family (devotional), music was a part of her lifestyle.

Did she intend to paint Tagore as a feminist? Mahua replied, “Tagore is a feminist, but with a difference.” She adds, “His women think the world of their homes, families, and children. However, they assert themselves fully when it’s a question of their identity, existence, or decision-making, which I feel is highly commendable.”

Swarchhanda (lit., rhythm and harmony), a sociocultural welfare organisation, spectacularly staged its 6th annual function. Its choir flawlessly poured forth classical and Raag Pradhan’s Tagore compositions. Jagate Anandayagne, Nrityero Taale (2), Maharaja Eki Shaaje, etc. The team members sang lustily, their unified rhythmic voices reverberating in the elite India International Center auditorium. Kolkata-based upcoming crooners Abhishek Banerjee and Shirin Soraiya consecutively presented perennial Tagore favourites, e.g., Sukhe Amaay Rahkbe Keno, Tumi J Amare Chao, and Chirosakha Chhero Na, in that order.

A stellar performance by the gorgeous Shama Rahman from Bangladesh made the evening memorable.

In collaboration with its other eminent associates, Impresario India, another NGO in Delhi, organised a gala event, with its audience comprising elites and former bureaucrats. A stellar performance by the gorgeous Shama Rahman from Bangladesh made the evening memorable. The Diva confessed her love and appreciation for Delhi’s discerning audience. Incidentally, she has performed in the Indian capital on various earlier occasions, notably during Tagore’s 150th birth anniversary celebrations in 2011. Her renditions, including Tumi sandhyaro mahala, Majhe (two) tobo dekha payi, and Je chhilo amaar swapanacharini, to name a few, enthralled the listeners.

Photos sourced by the author

By

By

By

By