Dr Roopali recalls that as a six-year-old, she had visited Bolpur with her mother and sister to celebrate Durga Puja. It’s a story of innocence, wonder and amazement of a child’s world – an exclusive for Different Truths.

UNESCO has listed Durga Puja in Kolkata as “An intangible cultural heritage of humanity.” I have not been fortunate to witness this spectacular event in Kolkata.

But I have incredible memories of Durga Puja as a six-year-old in Bolpur, about sixty kilometres from Kolkata. Those memories have tumbled out, and I have tried to recreate those childhood days, moments, and responses. Durga Puja resides in my DNA.

The train was slow, and the berths were hard. Mother took us from Jabalpur to Bolpur to visit her sister and celebrate Durga Puja with them. Father was busy soldiering.

The train passed through many places. Everything was green. A hollow sound would rise out of the river when the train crossed a bridge. Maybe the Loch Ness monster lived inside?

We had reached Bolpur. It was a famous village. Once upon a time, Robi Thakur (Rabindranath Tagore) lived here. People from all over the world came and still come to study here.

Shantiniketan, Mother says, is a university where classes are held in the open, under trees.

Shantiniketan, Mother says, is a university where classes are held in the open, under trees.

Since my sister and I were homeschooled, they told us many things daily.

As Bengalis call Rabindranath Tagore, Robi Thakur wrote poems and songs. He was a magician. English people wanted him. They tried to call him Sir, but he refused.

It was the month of October. Dhaak (war drums) were telling everybody that Ma Durga was coming. “Get ready. She is coming. She is coming.”

Ma Durga is the Goddess of infinite strength and has ten hands, and she rides a lion. Her eyes, they say, are like lotuses.

The green of the rainy months turned into bright red and orange.

The green of the rainy months turned into bright red and orange. Women were pasting red powder called sindur on their foreheads. They were busy colouring the soles of their feet red and wrapping their wrists in red bangles. They were dressed up like brides.

Haru Maama, their mother’s brother, returned from the big city called Kolkata. The English people call it Calcutta. Why do English people not pronounce anything correctly? Haru Maama was permanently grumbling about this or that. He didn’t speak any English except when he was angry. Then he would say, “bladdy phool”. It made him feel very important. We kids didn’t like him.

From Kolkata, he brought two small flat bottles filled with the red liquid Aalta. Only if you are married can you open the bottle and use it.

Mother, Mishti maima, Moyna mashi and Joya didi all began to colour their feet. Ma Durga was coming.

Boroon, who is eight-year-old, says Aalta is. goat blood from a fresh, slaughtered goat. Boroon is older than us, so we listen to him. Blood is squeezed out of a holy goat after the pujari moshai (priest) acts like he is the black Goddess Kali.

He then drinks the first rush of blood from the goat’s head.

He then drinks the first rush of blood from the goat’s head. Some people feel this blood is not the right one because of how the goat’s throat has been slit slowly. This “some people” is Haru mama. He says, “Only if it has been done in one stroke of the sword and Joi Ma, Joi Ma Durga, Kali etc., shouted then the blood is pure. No other names will do.”

God has many names. Mother says god has sahasra naam (a hundred names). That night, I dreamt of Mother looking like Mishti maima. She was riding on the back of a headless goat with a whip in her hand. The only thing that was not nice was the goat was a ghost. “Why are you staring at me like this?” Mother asked me the following day. “Does Father know?” I asked, staring at Mother’s blood-stained feet. “Know what?” She asked without paying attention.

“That you dip your feet in goat’s blood?” Mother looked up. She was frying pieces of Rui maach (fish) for Haru mama’s breakfast. “Where will I get goat’s blood even if I want to?” Mother has become frightfully cunning.

“Haaru mama brought for you. Boroon told me.” “Did he, now? Goat’s blood is perfect for my feet,” Mother replied. She was not afraid. “But it’s not good for the goat.” I started crying.

“Is that so? Then I promise not to use it again.” Mother said in a soothing voice. I couldn’t believe my ears. I fell on Mother to hug her. The Rui maach was frying away.

Boroon disappeared and was brought back home by Mr Batoball Mesho, who found him sitting under a mango tree shivering with fever and muttering, “I want to drink goat’s blood; I want to drink goat’s blood.” When Mr Batoball Mesho heard our story, he laughed. Now, we know that Aalta is made out of the crushed juice of the red Jobakusum flower.

In English, it is hibiscus. Batoball Mesho carries a small dictionary with him all the time.

In English, it is hibiscus. Batoball Mesho carries a small dictionary with him all the time. The orange designs on Moyna mashi and Mishti maima’s palms are made out of the leaf paste of the mehndi bush.

That night I dreamt of a garden full of flowers – red and white and yellow and in it, Mother walked wearing a red and white sari, her eyes like lotus flowers and her ten hands dipped red with henna. Her feet left jobakusum stains on the marble floor.

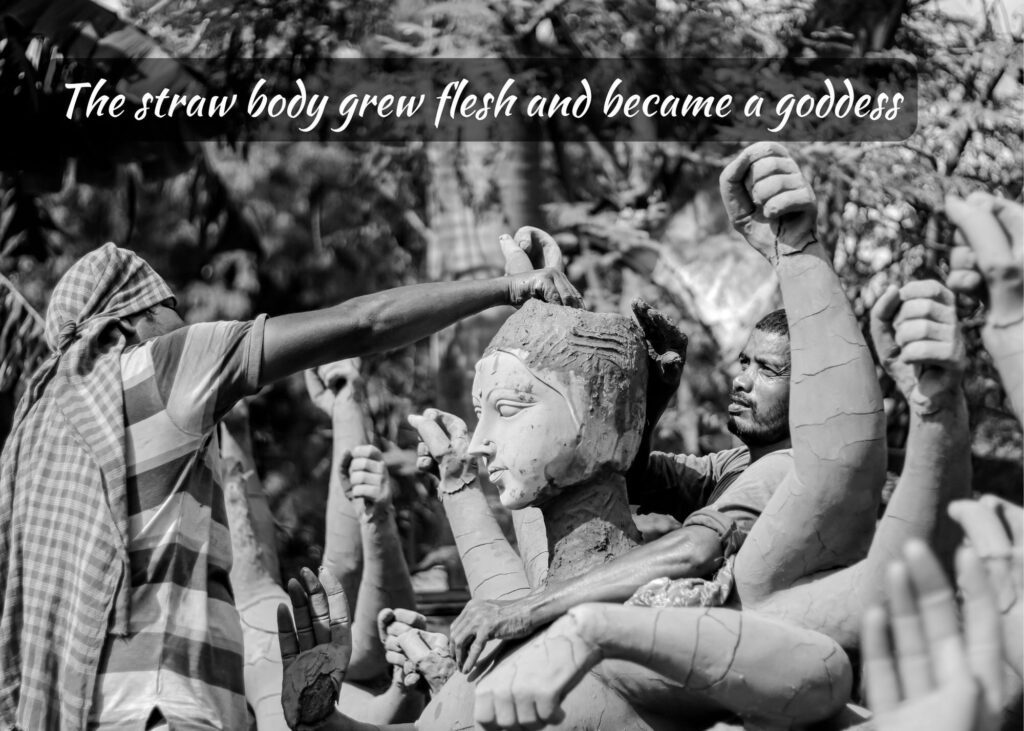

Bikashda is a sculptor. He makes statues only of gods and goddesses. For seven days, we whispered and nudged each other and watched him silently tie bundles of straw into shapes of hands, legs, and heads.

Before our wonder-struck eyes, the straw body grew flesh and became a goddess. Brown mud, white mud, and colours are made from leaves, flowers, and roots. Satin and gold clothes have changed all that straw into a goddess of incredible beauty and power.

“The mud comes from the house of a prostitute,” Sheila spoke in a low voice. She also kept giggling. Sheila is twelve years old. She is behaving like Sunita and her Giraffe friend.

A prostitute must be a significant person.

“Prostitutes are bad women,” Sheila whispered.

She again whispered, “What bad things do they do?” I whispered back. “Don’t ask dirty questions. I will report you to your mother.” She spoke aloud.

At night, Mother read out from a book full of pictures.

At night, Mother read out from a book full of pictures. “Like Athene of the flashing eyes, Goddess Durga rides the big, faced lion whose massive jaws bare fierce teeth and whose mane is long and golden.

She looks at us with eyes like big blue lakes of eternity. Her ten hands carry weapons of war and spiritual power: the sword, the spear, the shield, the axe and the lotus and the conch.

On the one hand, she holds the extended spear with which she pierces the monstrous evil heart of the asura, Mahishasur, who wanders about disguised as a benign buffalo.

On either side of Goddess Durga stand her obedient doe-eyed children. The goddesses of material and artistic powers are Laxmi and Saraswati. Kartika, the peacock-riding manly god of love and prosperity and the elephant-headed potbellied god of all beginnings, Ganesha, stand next to her.”

The buffalo head of the asura on whose blood-covered chest the Goddess has placed her small red foot. Aalta, the red hibiscus juice, is meant to look like her blood-dipped foot.

Haru mama piped up, “Keep evil down! The asura is black as hell, and the Goddess is pink and white just like English ladies. All Capitalists”.

We don’t like what Haru mama says. We don’t understand anything he says.

We don’t like what Haru mama says. We don’t understand anything he says. Boroon hit my neck with his knuckles and asked me to shut up and not show off my stupid English.

“There is nothing worse than a kaalo (black) Indian trying to be like a phorsha (white) Englishman,” Haru mama smirked.

“Oh, you shut up. Only Junglee Indians can’t speak English,” my sister yelled. Boroon pushed her hard and fell on a pile of half-painted hands and legs, looking like a broken goddess.

Bikashda, who had not looked at us even once as he worked all these seven days, now turned around and looked at us in a what-are-you-children-up-to look. And said, “What are so many asuras quarrelling here for? The Goddess will get very angry.”

I pulled my sister up, and the Famous Five returned home in groups of three and two: those who speak English and those who don’t.

The ninth day of the ten days “marks the end of the terrible battle between the white forces of good and the black forces of evil. “Look,” Mother pointed, “the Goddess is bright and magnificent. She has been installed on a high pedestal decorated with flowers and birds crafted out of the soft insides of water reeds. Her limpid lotus eyes look with deep compassion at the object of her wrath, the Mahishasura.

The long spear has pierced the heart of evil. Mahishasura is half buried under the floral prayers.

The long spear pierced the heart of evil. Mahishasura is half buried under the floral prayers. The Goddess does not deny him his share of divine forgiveness. The merciful Goddess instructed the evil asura to remain forever under her feet.

She says, “When flower prayers are showered upon me, they’ll fall on you too; when the sound of chanting and conch shells reach my ears, they will reach you too. And then you will find your Moksha. Your Nirvana.”

What is Nirvana? Salvation. Even Jesus on the cross had said, “Lord forgive him, for he knows not what he does.” Father Dudley had said so.

The Jaatra party (folk drama) was about to start. As the Goddess looked over us, we sat, mouth open. Then the curtains moved to show us how a man called Mir Kasim cheated Nawab Shirajudulla. The Englishman named Lord Clive was not English. He was the local nolin-gur tapper.

He was pasted with a lot of pinkish powder. A man called Company Bahadur was mentioned several times, but he never appeared on the rickety wooden stage.

We listened amazed as Englishman Lord Clive spoke in Bangla with an English accent.

We listened amazed as Englishman Lord Clive spoke in Bangla with an English accent. It was Shirajudulla’s wig with its loose curls, which flew from left to right as he said in a loud excited and sometimes king voice, which sent all five of us into belly-paining laughter. And we fell on each other as our breath caught in our lungs.

“It’s a story of greed, human failings, intrigue, and betrayal, which ended in the terrible battle of Plassey.” Mother tried to make us understand. We went home when the sun rose out of its bed, and its bright light touched the broken stage scattered with dead people, both dead Indian men and dead Englishmen. The Jaatra went on all night. The loudspeakers didn’t let us fall asleep.

The tired, about-to-fall-dead, and hungry curtain-puller left the curtain half open and ran away. We saw some of them yawn in the middle of loud clapping for the dead. Shirajudulla stood shaking his curly locks.

Bijoya Doshomi, a truck that carried stones from the stone mine eleven miles away, carried the Goddess away on the tenth day. Mr Batoball Mesho and his many nosy relatives scrambled onto the already full truck yelling shouts of victory because the Goddess is so strong.

That is not fair. Why do they throw her into the water?

Tilting forward, fear writ large on her face, the Goddess, went in the truck.

Tilting forward, fear writ large on her face, the Goddess, went in the truck. The truck rocked side-to-side and up-and-down, stumbling through the stone and gravel-strewn kutcha road—the hollow sound of conch shells and eardrum bursting drums.

She is taken away quite against her wishes by a crowd of people, who are very happy to drown her in the river, which makes its way across many miles.

My sister stood on the grassy bank of the road, full of stones and pebbles, and cried for the beautiful Goddess, who was taken off her flower-filled pedestal and bundled off to a watery grave.

The old widow with a twisted arm, who lives in a small room in Mr Batoball Mesho’s outhouse, patted her head, “Ma Durga will return next year at the same time. You can see her then.”

“But we won’t be here next year,” I announced. “That doesn’t matter,” The old woman spoke softly. “She will come wherever you are.”

Ma Durga, the Goddess of infinite power, comes home each year.

The years have gone by – one year at a time. Ma Durga, the Goddess of infinite power, comes home each year. This year too, the Dhaak is beginning to sound her arrival.

Faraway from the heart of Bengal, her presence is already being felt. The old lady was right. She will come wherever we are.

Picture design by Anumita Roy, Different Truths

By

By

By

By

Yes she will come whenever and wherever we are, beautiful throwback ma’am