In order to acquire a worldview for himself, Tagore strove to achieve a balance between Humanism and Naturalism, Individualism and Determinism, Hedonism and Asceticism, all of them being the various ways of apprehending the ultimate reality. This balance helped him determine his own perspectives on life and times, and his role as a literary writer and social interpreter. His Humanism made him apprehend the relationship between Man and Nature, the two essential components of the Phenomenon. His Naturalism made him realise the significance of Mother Nature as the gracious Being and the eternal teacher. Prof. Anisur examines the shaping of Tagore’s sensibilities, his ideas and ideals, in this eclectic write-up, as Special Feature. A Different Truths exclusive.

Ideas that have shaped nations and human destinies have not necessarily come from proclaimed philosophers; they have also come from poets and writers, musicians and painters, the so-called “unacknowledged legislators” of the world. While ethics, philosophy, spirituality, and faith, the four major domains of human knowledge, expresses themselves in graded manners, and qualify individually for serious critical attention, they also concretise as a body of human wisdom and call for collective appraisals in given times and places.

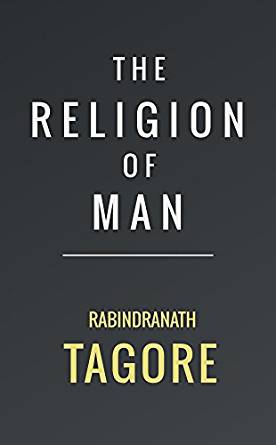

Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), like other creative artists, was no philosopher as such but was one of a kind, an intellectual major, who reflected profoundly on spiritual aspects of life in Sadhana (1913) and The Religion of Man (1937), the two of his more powerful discourses on divinity, spirituality, and man’s place in the larger design of Being. Drawing upon the concept of Brahma as the absolute truth, he examined the nature of good and evil, beauty and ugliness. This was an understanding of the phenomenon that while facts were many, the truth was only one, and that truth was Brahma.

Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), like other creative artists, was no philosopher as such but was one of a kind, an intellectual major, who reflected profoundly on spiritual aspects of life in Sadhana (1913) and The Religion of Man (1937), the two of his more powerful discourses on divinity, spirituality, and man’s place in the larger design of Being. Drawing upon the concept of Brahma as the absolute truth, he examined the nature of good and evil, beauty and ugliness. This was an understanding of the phenomenon that while facts were many, the truth was only one, and that truth was Brahma.

Religion or Faith, as a code of human conduct, informs man’s responses which Tagore projected as central to his understanding of life. In order to acquire a worldview for himself, he strove to achieve a balance between Humanism and Naturalism, Individualism and Determinism, Hedonism and Asceticism, all of them being the various ways of apprehending the ultimate reality. This balance helped him determine his own perspectives on life and times, and his role as a literary writer and social interpreter. His Humanism made him apprehend the relationship between Man and Nature, the two essential components of the Phenomenon. His Naturalism made him realise the significance of Mother Nature as the gracious Being and the eternal teacher.

Tagore’s perspectives on life and times reflect a fine blend of the late nineteenth and early twentieth-century worldviews. Being rooted in the Indian time and space, this worldview bore the best of the Eastern and Western views on life and times. Let us pick a few of the major ideational bases that inform Tagore’s view and vision of life and times. They relate to his views on education, society, nation, nationalism, universalism, politics, and women.

Education

Tagore laid great emphasis on the infinite capacity of human beings to learn and transcend the mundane limitations of life. They had the potential to transcend the lure of the world, as they were endowed with much greater powers than they could actually utilise. One of these powers, he believed, was the potential to educate oneself which reflected amply in his views on education. Like William Blake, a precursor of the Romantic Revival in England, Tagore rejected the tyranny of the formal and programmed modes of learning. Being liberally educated in literature, languages, arts, sciences, history; being well exposed to the knowledge systems of the East and the West; and being widely travelled in various parts of the world, he developed his own views on education. The concept of real education, he passionately believed, had to be liberated from the strongholds of classroom learning and traditional pedagogy. He sought, therefore, an idealist stance in conceptualising Viswa-Bharati, as a new site of liberal education in natural surroundings, and in a holistic manner.

Tagore strove to inculcate the traits of intellectual inquiry in the learner. This was his way of connecting with the world beyond and become a part of the global intellectual community. He, thus, developed his own notion of the guru and the shishya, based on personal bonding, which could result into the efflorescence of healthy emotional, intellectual, and spiritual life. In clear negation of the imposed British system of education, Tagore blended the Hindu mode of education with the Western ideals. His aim of education and his educational philosophy are best reflected in Song 35 of Gitanjali that represents a wish and a sense of pride and belonging:

Song 35

Were the mind is without fear and the head is held high;

Where knowledge is free;

Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls;

Where words come out from the depth of truth;

Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection;

Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit;

Where the mind is led forward by thee into ever-widening thought and action—

Into that heaven of freedom, my Father, let my country awake.

The song reiterates the significance of freedom, pride, truth, perfection, reason, thought, and action. These are the prized possessions that would keep all fears and fragmentations, narrowness and dead habits, out of our lives and lead us to the professed destination. Tagore’s effort at opposing oppression, untouchability, and his larger acceptance of the best tenets of other religions in terms of essential humanity, also underline his concept of complete education and educated man. This leads further to his understanding of Indian nationalism, and the possible role of the people towards consolidating the notion of national identity which, in turn, was yet another aspect of his project of education.

Society, Nation, and Nationalism

While thinking of how to educate oneself, Tagore was constantly preoccupied with the idea of society, nation, and nationalism. Each had a graded relationship with the other in his scheme of thoughts. While society was a smaller unit of homogenous or heterogeneous humans put together, the nation was a larger body that got defined in the process of identifying its goals. Nationalism, as different from society and nation, was the spirit rather the body which qualified for a critical understanding in terms of people who form the basis of both, the society and the nation.

In his essay entitled “Nationalism in the West”, Tagore says “…neither the colourless vagueness of cosmopolitanism, nor the fierce self-idolatry of nation worship is the goal of human history”. In saying so,  he developed a stance that rejected the idea of the so-called “nation” by which he did not mean any particular nation. In fact, the very idea of “nation”/“nation-state” which is a post-independence/post-colonial concern was conceived then by Tagore as a liberal space with “economic and political union of people … a whole population … organised for a mechanical purpose”.

he developed a stance that rejected the idea of the so-called “nation” by which he did not mean any particular nation. In fact, the very idea of “nation”/“nation-state” which is a post-independence/post-colonial concern was conceived then by Tagore as a liberal space with “economic and political union of people … a whole population … organised for a mechanical purpose”.

While reflecting upon his idea of nationalism, Tagore was completely conscious of the problem of races that stared in the face and posed a situation of crisis in achieving homogeneity. He was also acutely conscious of the singular nature of Indian history that presented a unique stance of incessant resolution of opposite and dichotomous conditions. Tagore knew well that it resulted from the unique position of India as a multi-religious and multi-ethnic country which could best be reconciled spiritually rather than politically. Tagore was, thus, opposed to irreconcilable social structures that kept people apart rather than brought them closer to belong to a homogenous conglomeration of communities. He was not in favour of letting the people to be dogged by real and imagined divisions and oppressive hierarchical structures. Tagore was a votary of liberalism and liberty and made a distinction between society and nation. He viewed society not as a replica of the western societies but only as a whole that was conditioned by reconciliatory principles of existence. He believed in a regulated body of human beings who had come to stay together in a relationship of understanding. As opposed to this, nation to him was a collection of people who had political ends, unhealthy designs on other spaces, and most importantly believed in power politicking. As such, Tagore was opposed to a kind of political freedom that asked for forfeiting moral freedom. This notion of society, nation, and nationalism led him further to concretise his ideas on universalism and internationalism.

Universalism and Internationalism

It has been repeatedly asserted that Tagore was a global citizen but it needs to be emphasised that he was both a proclaimed Indian and an assertive global citizen. He, in fact, strove to reconcile the two and emerge as a product of a larger and liberal world order. He aspired to live in a world that struck a fine balance between different colours and cultures representing a variety of races, languages, and ethnic configurations. Tagore’s craving for cosmopolitanism verged on certain idealism; it was more an object of desire than of realisation at a political level. This is well testified by the turns of event in the post-colonial phase of history in spite of the great advocacy made in favour of multiculturalism, diversity, and tolerance.

Politics

Tagore was no politician but held views that reflected upon his keen awareness of contemporary political issues. He opposed imperialism and supported Indian nationalists’ bid for freedom. The renouncement of his knighthood after the Jallianwalla Bagh massacre is a significant case in point. This led him to come up with notes of remarkable confidence in songs like “Where the head is held high” and “Move, even if you are all alone”.

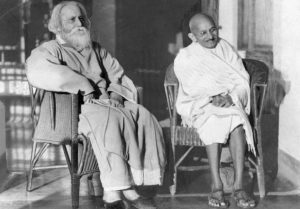

This confidence urged him to disagree even with Gandhi on significant issues like the Swadeshi movement as a typically Brahminical and metaphysical non-reality. He did not conceal his opposition to Gandhi’s spinning wheel also. He believed that discarding foreign clothes, foreign language, and spending time at the spinning wheel was not worth the effort put into them for gaining independence. Similarly, he rejected his plea on the earthquakes in Bihar as a retrograde way of looking at a tragedy that was a scientific reality rather than a consequence of divine wrath. Tagore’s significance in these and all matters that reflect his perspectives on life and times do not lie in any kind of insistence but on the truthful argument of a case. This, in itself, was a testimony of his liberal attitude towards life in general. This is further borne out by the respect he showed for those who did not agree with him, more importantly, Gandhi, although both of whom praised each other for their individual merit. Incidentally, I am tempted to refer here to a poem that a major Egyptian poet, Ahmed Shawqi, wrote in which he eulogised Gandhi:

Get up, O the people of Egypt!

Salute the Indian hero.

When the East called out

Gandhi lent his support

He united Hindus and Muslims

With love and sympathy.

Hey Gandhi!

The great Nile salutes you

Women

While Tagore’s respect for human beings of divergent views is one aspect of his overall personality, his views on women as a reservoir of infinite potential, and as a paragon of beauty, are yet other aspects that deserve our attention. He acknowledged that they had long been subjected to oppression in a patriarchal social structure, and they needed a release. They deserved respect and sensitive treatment as they represented the finest female virtues like modesty, chastity, and grace. He also evokes them to act, participate, and seek a place for themselves in a social structure.

His stance on women may be seen in how sympathetically he viewed some of the real and imagined  women. The cases in point of one kind are his niece, Indra Devi Chaudhriani, his sister-in-law, Kadambari Devi, and his mother, Sharda Devi from within his own family, and of Victoria Ocampo and Ranu Mukherjee in whom he saw the relationships of the most ambivalent kind. While Ocampo, who was later named Vijaya by him, stood out in a mysterious relationship with him, Ranu was the picture of his daughter Bela whom he lost in the early thirties of her life. Both the relationships matured with years and ultimately became more mysterious than explainable. Tagore’s view on women can be testified in many of his fictional works of whom Chitrangada is a prominent example. She is remarkably confident, even audacious to a degree, and stands apart as a strong personality. Tagore saw in women immense potentiality that could be realised in real terms. He viewed them in an Indian socio-cultural context rather than the western context that was rather alien to the Indian sense and sensibility.

women. The cases in point of one kind are his niece, Indra Devi Chaudhriani, his sister-in-law, Kadambari Devi, and his mother, Sharda Devi from within his own family, and of Victoria Ocampo and Ranu Mukherjee in whom he saw the relationships of the most ambivalent kind. While Ocampo, who was later named Vijaya by him, stood out in a mysterious relationship with him, Ranu was the picture of his daughter Bela whom he lost in the early thirties of her life. Both the relationships matured with years and ultimately became more mysterious than explainable. Tagore’s view on women can be testified in many of his fictional works of whom Chitrangada is a prominent example. She is remarkably confident, even audacious to a degree, and stands apart as a strong personality. Tagore saw in women immense potentiality that could be realised in real terms. He viewed them in an Indian socio-cultural context rather than the western context that was rather alien to the Indian sense and sensibility.

Conclusion

Tagore was essentially a creative genius who like others of his type and tribe had individualistic perspectives on life that may not be called philosophy in the strict sense of the discipline. He had, however, philosophical moorings, whose works grew akin to philosophical sketches in a creative mould. His views are that of a poet, and of one who had his essential affinity with the fine arts. This imparted a certain romantic tinge to his perspectives on life and times. They were based in an idealism that Tagore savoured. He configured his views and visions in fictional terms now, now in real and concrete terms. He obliterated the distinction between art and reality by bringing art closer to life. As such, there can be two ways of looking at his perspectives on life and times. One may be explored through his imaginative reconstructions of reality in his art forms, and the other may be found in his prose writings where he is face to face with realities and does not represent his thoughts in metaphoric terms. The two aspects are eminently reconcilable, and the two taken together, compose and constitute the great song of freedom that he chose to sing all his life.

Photos from the Internet

#RabindranathTagore #TagoreAndIdealism #WomenAndTagore #NationationalismAndTagore #TagoreAndUniversalism #TagoreAndPolitics #TagoreAndEducation #TributeToTagore #DifferentTruths

By

By

By

By

By

By

A beautifully crafted article. Anis Sir has brought in so many ideas about a man of ideas, all in one place. Wonderful indeed. Men like Tagore are difficult to understand, but after reading this article, I think I will now go read about Rabindranath Tagore.