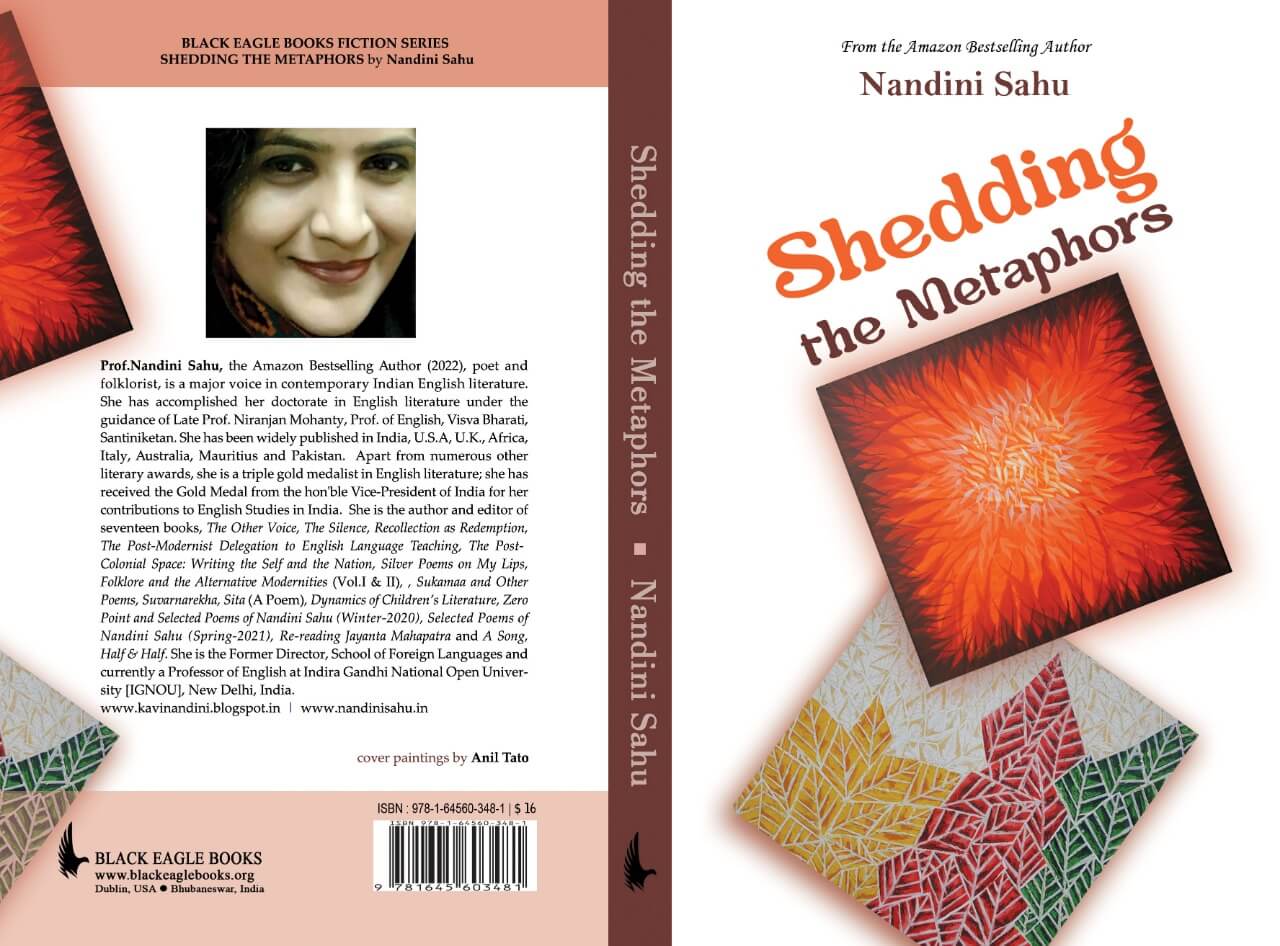

Nandini Sahu’s twelve-story collection Shedding the Metaphors is intriguing. Shibangi’s book review covers love, loss, redemption, and identity – exclusively for Different Truths.

Shedding the Metaphors (2023) is an intriguing collection of twelve stories of myriad thematic concerns by the prolific writer Nandini Sahu. The highlight of such a diverse collection is that it never attempts to be didactic, or as Sahu says in her Preface, her stories are not ‘preachy’ (9). The book opens with a fascinating poetic preface which can be perceived as a critical introduction to the collection itself, an accompanying piece of literature. It remarkably bears the traces of Sahu’s outstanding poetic calibre.

Shedding the Metaphors has a gripping title arousing the readers’ curiosity from the first page. What significance would a human life hold if entrenched in the art of ‘letting go’? This nuanced philosophy is reiterated in the twelve stories as the readers question their prejudices, internalisation and long-held conditioning put to critical thought. Thus begins the process of learning and unlearning, which marks the life of a well-thought-out individual. For Sahu, this act of letting go tends to attain ‘nirvana, abyss, all-inclusive, nihilistic, irrationally rational, non-judgemental, romantic’ (9). Being self-conscious, she knows it is challenging to accommodate all such finer metaphors of life in one living. Thus, she sheds her Id, Ego, and Superego as the Brahma (ibid).

Nandini Sahu dons multiple hats: a writer, teacher, folklorist, poet, and theorist.

Nandini Sahu dons multiple hats: a writer, teacher, folklorist, poet, and theorist. These myriad roles have enabled her to sharpen her skill as a master storyteller as well. Men have historically regulated speech and writing. This deliberate silencing of women has been questioned as Sahu lays bare every throb of her women characters while writing and speaking. Having a tone of orality as the diverse characters speak, she rightfully explores the art of ‘storytelling’. The stories are bound by a common theme of the symbolic and symbiotic relationship between different elements of nature, the animate and inanimate. Being a theorist of gender studies, Sahu undertakes an intersectional and empirical analysis of gender politics in her stories. Her characters belong to different socio-political backgrounds and are at the forefront of the battles they are waging in their capacity. She employs ‘private mythology’ to carve out the characters in their quotidian lives (14). As Sahu emphasises, her characters’ endeavour to probe into the epistemological connection, into the art and the science of knowledge’ (11). She focuses on and interrogates the creation of multiple dichotomies as they exist in society, nature versus culture and natural versus unnatural. Thus, her writing vis-a-vis storytelling becomes a medium of protest.

The story, That Elusive Orgasm,revolves around an incestuous relationship between a father and his daughter, Jhumpa. The near absent-present mother, who is paralysed, is complicit in this act, propelling the reader to delve into the layered aspects of how patriarchy operates in society. The idea of paralysis cripples not just Jhumpa’s mother physically but also her own life metaphorically. Trying to escape from the clutches of her past life and seeking to reinvigorate her present, she momentarily seeks the shelter of religion. The readers are exposed to the ideas of purity and sin while bestowing divinity to Jhumpa by her father. Non-satisfaction and non-fulfilment of female sexual desires are often considered taboo topics. This is further problematised when the story reveals that the father provides Jhumpa with the ‘elusive orgasm’.

A realm where men can exert their power and dominance is home.

A realm where men can exert their power and dominance is home. As John Stoltenberg suggests, ‘patriarchal culture… emotionalises and psychologises the right of men to own women and children as property’ (50). This turns a blind eye to the violence inherent in relationships based on objectification and possession of other human beings. Sensing the hierarchy of power in the dynamics of the family, the father becomes powerful and the mother powerless. This abuse of power within a family and the relationship it entails is reflected in the story. A clear breach of trust results in a young girl questioning her identity and her feeling of helplessness and subordination.

There is still a deafening silence surrounding incest in the country. Mothers are expected to be a source of emotional nurturance in the family. If they cannot give love and care to the family, they are labelled as abandoning the family. She is considered not fulfilling her maternal role if she does not restrain the father in an incestuous relationship. Such mothers are considered ill, weak, or downtrodden to protect their daughters. By not delving into the role of the mother in this story, Sahu de-emphasises the part of the mother in this dysfunctional family.

Despite his professional achievements, Dr Panda complies with bestowing credit upon his wife.

The story, Alternative Masculinity, focuses on the lives of Dr Harihara Panda, an academician and his wife, Savita Panda. Savita’s life is consumed by looking after her husband’s needs, which verges on controlling his day-to-day affairs. Despite his professional achievements, Dr Panda complies with bestowing credit upon his wife. As the relationship gradually unfolds, the readers have an insight into the manipulative husband who had ployed to get Savita’s property signed in his name on the pretext of securing it. The narrative makes us question who is the gullible one between them. The hegemonic models of masculinity versus alternative masculinity are ingeniously dissected in the story. Harihara legitimises the power of consent from Savita, thus not only perpetuating gender inequalities but also reproducing these. The concept of alternative masculinity objects to the oppression of women. It questions the hegemonic male behaviour and embraces a more egalitarian form of manhood. As the story commences, their colleagues and peers of Harihara pity him because of his stifled existence, but the ‘masculinity’ exuded by Harihara makes him a more threatening figure.

The story, Shadow of a Shadow,revolves around the life of Ragini, and it runs parallel to Sappho, the queer Greek poet. The poetic opening resonance with what is to follow. It explores multi-faceted love. It impels the readers to interrogate if there is a natural love and an unnatural love as dictated by the heteronormative society. This society punishes errant sexual behaviour. The story draws upon state-sponsored violence while discussing the fate of Sappho and her poetry. It interrogates family and educational institutions as the ideological state apparatus that tries to cage the free-spirited Ragini. Because of the vacuum in their lives, Ragini and Sunita forge an alliance and solidarity, culminating in love.

Queer ecofeminism is distinctly felt in this story.

Queer ecofeminism is distinctly felt in this story. As Sunita and Ragini rise against compulsory heterosexuality, the need to appreciate the diversity of the natural world is reinstated more firmly. This narrative topples the hierarchical pyramid, which is representative of systemic oppression. It is nature which narrates the brutality of sexual assault that Sunita had experienced, which creates her aversion towards men in general. It raises questions on the role of legal institutions in supporting the survivors, the ugly nexus among the power-driven classes. In the final step of culminating their relationship, a certain rawness exudes in the physical touch. For others, ‘it was a scary echoing sound as if a wild beast was gorging on some raw flesh and licking, relishing it’ (98). But this union epitomises comfort, warmth, togetherness, and closeness for Ragini and Sunita. The metaphor of food is used deftly to decipher bodily hunger, desire, and appetite for the beloved. The final moment of union for Ragini and Sunita was the last time they loved each other. One might wonder why Sunita and Ragini’s story is so crucial. It is imperative to listen to their story because Sahu captures the occasion to speak, marking their explosive entry into history where historically, they have been oppressed because of their sexual preferences. They are initiating their journey in the political process.

In the Wild Stream, the readers encounter a heart-rending story of Mami Pradhan, ‘an eternal dreamer’, owing to her class position. It explores the bitter truth regarding the dire situation an individual encounters when they are trapped in poverty. Aspirations and ambitions of ‘lower’ class people are crushed in broad daylight. Belonging to a below-the-poverty-line category will not determine their personality and identity.

Being God’s Wife is part of Sahu’s life narrative and a tribute to her father.

Being God’s Wife is part of Sahu’s life narrative and a tribute to her father. She looks into the magnanimous figure that her father was, equating him to a demigod. While she is nostalgic for her father, the narrative also peeps into the author’s personality. Her Baba played an integral role in instilling the philosophy of literature and creative writing in Sahu.

Be it Jhumpa, Mami, Savita or the other powerful female characters, women are not seen as a homogenous entity but studied through the intersectionality of gender, caste, and class. Sahu raises the need to forge alliances and solidarity across womankind to challenge the hate directed against them. Sahu’s characters arrive gracefully and vibrantly across all ages as they are at the threshold of a new history, in the process of becoming in which several histories converge. Sahu’s writing is in tandem with what Hélène Cixous had so impactfully said at the beginning of her essay, The Laugh of Medusa,

A woman must write herself: must write about women and bring women to writing, from which they have been driven away as violently as from their bodies- for the same reasons, by the same law, with the same fatal goal. A woman must put herself into the text- as into the world and into history- by her own movement. (875)

Women characters populate Sahu’s stories … which is often considered a taboo topic, love and sexuality.

Women characters populate Sahu’s stories bringing onto the discussion table that which is often considered a taboo topic, love and sexuality. Writing about self can enable women to claim her body, her sexuality, and her inherent strength, which have been forcefully kept under wraps. Writing is an avenue for change, to process the subversive thoughts that could bring about social and cultural transformations. Cixous argues that a woman must write to record ‘the indispensable ruptures and transformations in her history’ (880).

The collection is not a memoir, but it is written in an autobiographical tone whereby Sahu draws inspiration from the diverse quotidian characters she meets, capturing their infinite complexities. She acts not only as a narrator but also as a critical commentator. She uses silence as a resounding speech for almost all her female characters. She uses humour in the narrative to momentarily lighten the atmosphere while simultaneously drawing the readers to ponder the profound philosophies of life. A remarkable feature of all her stories is the thought-provoking conclusions, and it also draws upon justifying the title of her story. While engaging in the rhetoric of inclusivity, she discusses love as flawed and platonic. She searches for a better world where love attains fulfilment as her characters experience gradual awakenings.

Works Cited

Cixous, Hélène, et al. “The Laugh of the Medusa.” Signs, vol. 1, no. 4, 1976, pp. 875–93. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3173239.

Sahu, Nandini. Shedding the Metaphors. Black Eagle Books, 2023.

Stoltenberg, John. “Eroticism and Violence in the Father-Son Relationship.” Refusing to be a Man: Essays on Sex and Justice. UCL Press, 2000, pp. 49-64.

The reviewer sourced book cover’s photo.

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By