Dr. Roopali reviews Days V, a poetry collection by Sarita Sharma, a feminist poet. An exclusive for Different Truths.

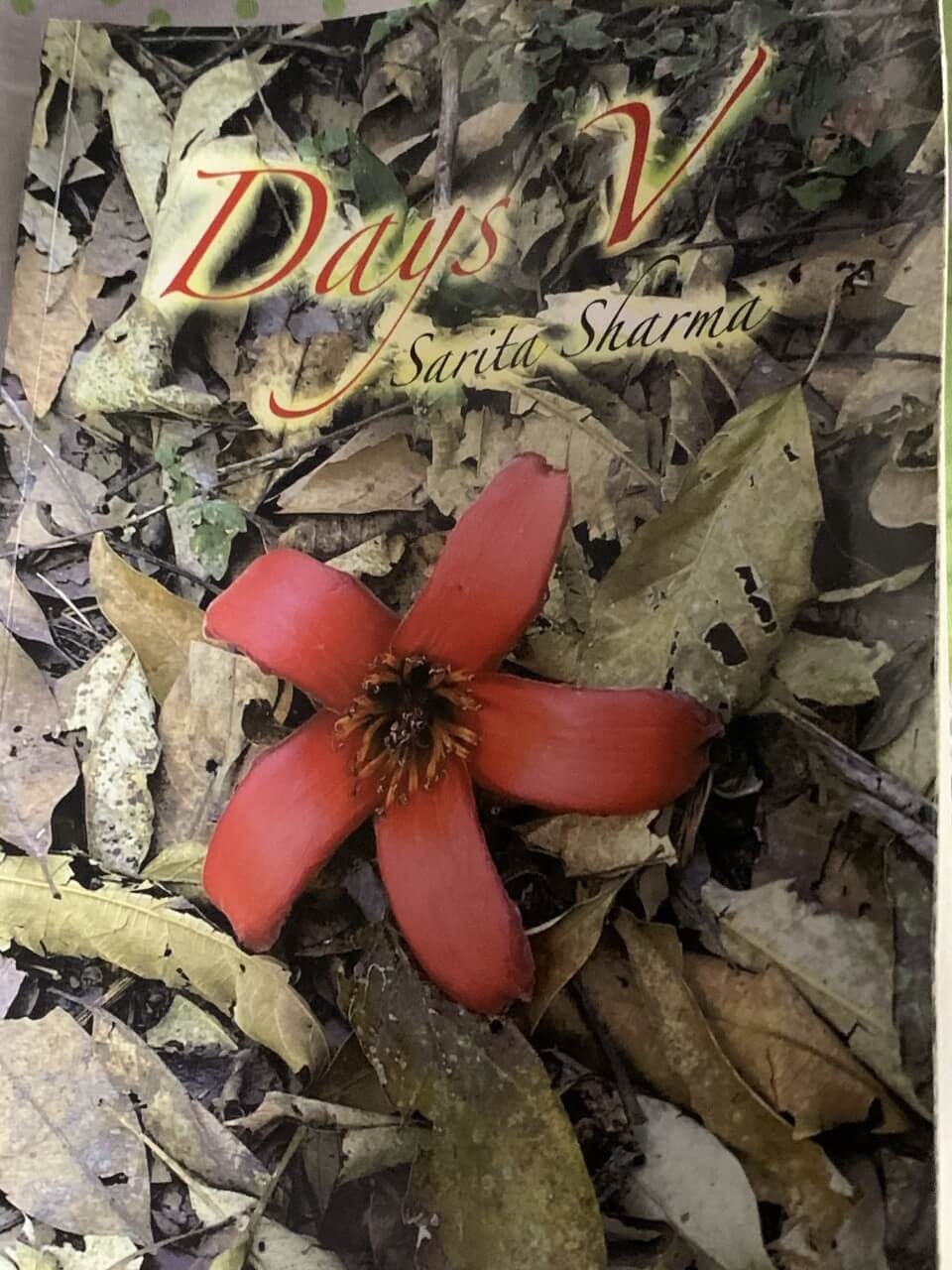

Days V: Sarita Sharma

Published by: Partridge 2021

The late Kamala Bhasin poet, activist, social scientist, defines a feminist as a person concerned about issues related to women. The women’s movement in India and elsewhere worked to negotiate an equal social and political space for women.

Prolonged activism has brought about some significant strides in empowering women. Literature and art have played a vital role in disseminating ideas and creating awareness.

Societal Inequities

In India, societal inequities continue due to obscurantist religious and customary practices. Women are held prisoner in the name of dharma and karma. The internalising of patriarchy by women has led to acceptance and surrender. This has been detrimental to their fulsome development as citizens with equal rights.

Somehow women’s achievements are seen as a marvel. A rarity to be celebrated. We are referred to as women poets, women police, women chefs, women judges, women doctors…and on and on it goes. Meanwhile, women’s biology is used in diabolic ways to disempower.

Days V, a brilliant poetry collection by Sarita Sharma, places her in the hallowed position of a strong feminist poet.

Days V, a brilliant poetry collection by Sarita Sharma, places her in the hallowed position of a strong feminist poet. In her poem “Made Woman” she sums up her feminist stand. “I have been blamed /hit/ belittled/ rendered invisible/mute.” Clearly a poet activist she claims our attention to the continued inequities in gender relations.

These poems are not simple literary ruminations. The bold title Days V (five) attempts to demystify the mystic menstrual cycle embedded in our culture. At the core of her poetic expression lies the awareness of a highly divisive gendered space.

Identity Issues

In her introduction she writes, “Being woman is difficult. Identity or the lack of it rather,” she emphasises, “features prominently in my psyche as a woman who had to fight many subtle mindsets to come out strong. I sing of identity, I even sing of the lack of it…. of houses dreamt of and abuses raining when least expected.”

Taking a cue from her words we look at how her fifty-two poems break the silence. Although they seemingly speak in a gentle voice it is a firm one, which speaks of brutal matters. It endorses the saying that there is nothing stronger than gentleness.

Constantly living in fear of sexual assault and abuse, women are all victims of a suffocating patriarchal mindset.

These poems are not to be read as the personal stories of the writer’s experiential angst. The poet is an authentic witness to the female condition. For women, there is no escape from subtle or brutal experiences. Constantly living in fear of sexual assault and abuse, women are all victims of a suffocating patriarchal mindset.

The poet compels us to look at a woman in her five days. The deep-rooted ostracism associated with those five days of menstruation spills into the psyche of a society. Both men and women are products of a deep-rooted patriarchal society.

Highly Gendered

The humiliation associated with a primary biological function is highly gendered. It is the very essence of procreation and motherhood and yet a matter of shame. The five days reoccur. Month after month year after year. At the end of it all a woman is left with very little. She “ceases to exist.”

The poems pick up on the many faceted lives of women marked by this damnation. Ironically, the five days of hiding are all revealing. Female blood is vile. Its presence is a proof of chastity. Its absence is a mark of infertility, deviant behaviour, and aging. All three render a woman useless and unwanted.

A woman’s very existence is schizophrenic to say the least. In I, the “many masks” are an indicator….

The first five poems are entitled ‘the schizophrenic mind’. A woman’s very existence is schizophrenic to say the least. In I, the “many masks” are an indicator…. Hence the empathy. Full of poignancy and a sense of loss of identity in the midst of multiple identities. “My schizophrenic soul” she laments in Alzheimer’s disease.

The image of the elderly man reading a newspaper evokes deep-rooted contempt and animosity. Somewhere buried is the collective memory of the old man as a young bullying brutal sexually assertive male. Now rendered useless in old age. The hidden triumphant note is followed by one of the females ageing with “dead stories and past dreams.”

Domestic Violence & Extramarital Affairs

II and III continue the dichotomous and dead sexual desire between couples. The domestic violence associated with extramarital affairs. Throughout a sense of loss pervades. The loss of menstrual blood is in itself a loss of motherhood.

Women pandering to the happiness of men who soon tire of them haunts the schizophrenic space. “Overworked brows”, “unwashed hair”, “she who has no share in it”, “no role whatsoever”, “reduced to a dirty farce”, “we cease to dream”, “to move on” are phrases that appear throughout the poems.

A loss of life metaphorically and literally. This sense of loss seeps into every poem…

Days V marks those critical five days when you are stigmatised as a woman. To completely break free seems if not impossible then certainly difficult. It is a repetitive circle. A loss of life metaphorically and literally. This sense of loss seeps into every poem rendering an ache which is all pervasive.

The title poem Days V is a brutal poem. It tears aside the curtain of dark ritualistic responses to menstruation. This harsh expose of the “stain of shame.” It is to be “shunned” and placed in a dark corner by “my mother and grandmother.” The internalising of patriarchy and its propagation through female agencies is clearly generational.

The poet laments how one ceases to exist those five days.

Sense of Shame

Father, the patriarch, totally ignores her presence. She is acutely aware of his sense of shame when she was born. Women carry out the expected diktats and thus become perpetrators, too.

The mere birth of a girl itself carries a burden of guilt and shame of both mother and child.

“I who shamed him /since the day /I cried out of my mother’s womb.”

Connecting the disappointment to the daughter and the dowry that must go with her. Words like “donated”, “bounties”, “my parents never possessed,” highlight the plight of women as burdens.

The poet packs each poem with many issues related to women.

The poet packs each poem with many issues related to women. They are life experienced as well as intimately observed. A quiet unstated sense of sisterhood persists.

Random Thoughts I and II raise the question of the denial of female sexuality and desire. That which is hidden under a “veil”. The “veil” which is gendered, the “veil” which is acutely patriarchal, the veil which is real and invisible. The feminist poet questions the deafness and the deliberate shut down. There is action now! “The desire to tear it, burn it to ashes, so that the curse could be broken, and the tongue redeemed!”

Loveless Relationships

Loveless relationships dot the landscape of women’s lives in Sarita Sharma’s poems. Be it the Bai (maid) in “Why are you late Kanta Bai” whose life is full of brutality and lust. Her body a sexual vehicle where the eyes of her male employers are constantly following her. The swollen eye an indicator of domestic violence.

“Is this love after all” is a poem which graphically describes the pathetic mental state of the woman victim of domestic violence. “I scream I cry all without a voice/I rave and rant all without a voice.”

The acceptance of daily violence as the norm is typical of women’s lives.

The acceptance of daily violence as the norm is typical of women’s lives. The undignified and subhuman existence cuts across social strata. The poet plumbs the psychology of victims of domestic violence.

The low self-image convinces the victim to take the blame. There is immense pathos in the effort to look beautiful and to rouse desire to combat rejection.

“But ahh the love that binds so and blinds so the love of life of roof over the head of a belly that sleeps in grains A place to call one’s own.”

The mother hopes the son will take care of her.

Nesting Needs

“A House of Her Own” also images longing and belonging. The desire for a house of her own. Every woman’s nesting needs. In a big city living in a rented dingy dark room this dream remains a dream.

“I am a small-town girl “presents an autobiographical vignette. Sarita Sharma the poet calls herself one “who has survived the lack of opportunities and the lack of opportunities.”

The empty nest as children have left for better climes and better times is found in “autumnal breeze.” The waiting patiently for a telephone call resonates with mothers.

Women writing is a political act. They occupy all spaces.

Contrary to belief women do not only write about the female experience within the domestic space. Women are citizens with constitutional rights. Wars, disasters, climate change, ecology, education, health, economics, and politics are also women’s concerns. Women writing is a political act. They occupy all spaces.

Sarita Sharma’s poetry reaches out to the single male in “Status Single.”

Looked upon as a predator and kept at arm’s length, the single man is a lonely man. “I am nobody’s dad/ husband to none / a single man.”

Gorkha: An Outsider

Two poems are dedicated to the Gorkha. “You see him and still don’t /you hear him and still don’t.” Both poems “The Quintessential Gorkha” and “Gorkha and Land” are protest poems on behalf of the Gorkha, an integral part of India, yet an outsider. The racist attitude meted out to the Gorkha people is ignoble to say the least. They are an integral part of India’s Defense Forces.

In “Kantabai on a Holiday” we look at how the lockdown situated the working woman. The first ever official break from drudgery in thirty years. It was like reclaiming her own home. And then there is the humour of her watching with suppressed pleasure her husband getting a beating from the police for loitering.

Sarita Sharma’s is a sensitive penetrating mind.

Days V is full of many poetic expressions. Sarita Sharma’s is a sensitive penetrating mind. It enters the experiences of others as well as looks at the complex similarities of her own experiences.

Her poetry does not mince words, nor does it try to hide behind academic jargon. The poems are for us to read and to learn empathy and compassion. They weave in the details that leave little for us to imagine. Yet it is in the simple conversational tone that the punch of the iceberg lies.

Everyday Stories

These poems tell us stories. Everyday stories. A deep understanding of the passing of time expresses itself in a sense of loss. The unappreciated unrequited lives of women and others especially touch the poet’s indelible ink. The book of poems curated during the pandemic is shadowed with sadness. It looks deeply at women as they live out their lives.

The collection concludes with “A Prayer.” For peace and wellbeing. Although the poet attributes it to the Prime Minister’s call’ it is the poet’s soul calling for “solidarity, unity, compassion and hope.” It appeals for dispelling the darkness in the lives of women. A clarion call for the solidarity of women and a hope for our sisters and humanity.

“Until lions have their own historians, tales of hunting shall always glorify the hunter…” African proverb. Dr Sarita Sharma successfully takes on the historian’s role.

Cover sourced by the reviewer

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

What a brilliant review a scholarly approach in detailing way, wonderful ma’am God bless