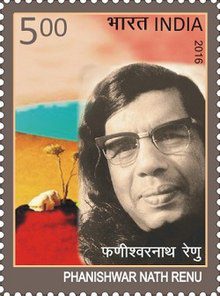

Dr. Nachiketa profiles the revolutionary writer, Phaniswarnath Renu (1921 – 2021), on his centenary year. His 100th birth anniversary was on March 4, this year. A tribute, exclusively for Different Truths.

The middle-class enlightenment of Hindi literature radiated from the old cities getting creative impetus from Benares, Allahabad, and Delhi, later, during the post-independent era, is ruled over by the urban centers of North India. The legacy of Premchand was ignored although the stalwart raised flagship project.

Renu was the first novelist, a value-added writer, who returned to the rural milieu and drew the readers towards village, altering the direction of westward flow of ideas to eastward and reestablished the Premchand schooling. Modern Hindi writers were busy exploring contemporaries or urban life, neo politico-cultural accessories in their literary worlds.

Renu was the first novelist, a value-added writer, who returned to the rural milieu and drew the readers towards the village…

Renu emerged from linguistic motherland, in a village of Purnea, a district of northeast Bihar, (now Araria) surrounded by the Bengal Santhal pargana, Nepal, and Bangladesh. Renu innovated a language of his own, incorporating the folk song, folktale, folk drama, local myth, local festivity, lost dialect forms, rural pronunciation restructuring, indigenous forms of literature. A self-declared novelist of regionalism, wonderful maker of a village universe in his fictions or song making every reader as fellow villager. Representation runs through rural vocabulary, code of behaviour, non-artificial village life, and untranslatable life experience.

Renu is Phanishwarnath Mandal. He was born on March 4, 1921, at Aurahi Hingana, in Purnea District, Bihar. His family belonged to well to do peasant family. His father, Shilanath, was an educated member of the Arya Samaj, an activist of nationalist politics. Renu was educated in India and Nepal. His primary education was in Araria and Forbesganj. He did his Matriculation from Biratnagar, Nepal while staying with B P Koirala family and he did IA from Banaras Hindu University.

The village stayed in his heart. Renu’s style of regionalism is striking. The narrative is a collage of lyric material…

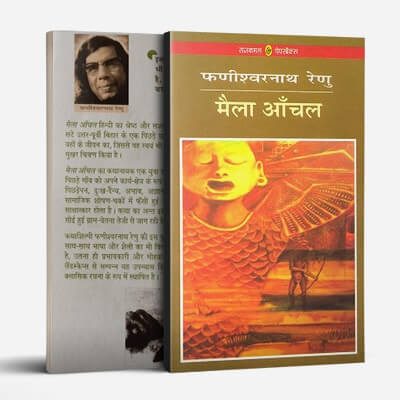

From this intellectual grooming, his author life started. The village stayed in his heart. Renu’s style of regionalism is striking. The narrative is collage of lyric material with melodic dimension of the songs in audiences’ mind that resonate his wordings. In his legendary novel, Maila Anchal, he cited twenty different Maithili song types. Song of lifecycle ceremonies like sohar (birth songs), nachãrl (marriage songs), and samadãun (mourning songs) seasonal songs of Phag, Jogtrã, Bharauva, Hori, Chaiti, Bãrahmãsã and Jhumar for the rains; also, other devotional songs.

He imported traditional literature into his fictional medium, articulating song as the voice of the people to represent their cultural heritage. It appeared as a structural pattern in Renu’s fiction, Tsrikasam, Rasapriyã, and Maila Anchal.

Maila Anchal is proclaimed as the second greatest novel, after Premchand’s Godan.

Renu’s debut in literature world in 1946, with his first short story, Batbaba, published in Vishvãmitra, in Calcutta, next journal of Socialist Party named Janata, but he got wider popularity with the publication of his first novel, Maila Anchal, in 1954 attracting a larger Hindi world to receive the President’s Award for best novel of the year 1955. Maila Anchal is proclaimed as the second greatest novel, after Premchand’s Godan. What Jha (2012) states, “His innovative use of language forms distinguishing him from his predecessors like Premchand; his mobilisation of an enormous amount of information, which I shall call the cultural memory of the region; and third, his technique of storytelling. Together these three produce an archive for the reconstruction of the region at a particular historical juncture. This archive draws our attention to the apathy accrued to the dynamics of space by a large section of littérateurs as well as social scientists otherwise obsessed with the time.”

His Parti Parikatha, another classic novel of 1957, and his first collection of short stories, Thumri (1959), were wrapped under regionalism too. And this approach continued in Julus (1956), the novel, and Adimratri ki Mahak (short stories, 1967). The essence of rural Bihar with unheard melodies. An altered dogma came out from Dirghtapa (1963), Kitane Chaurahe (1966), and Aginkhor (1973), when Renu dissected the rural arrangements for the urban cosmopolitan trend.

Parit Porikotha (The Tale of Wasteland) dealt with massive concept of different conflicts.

The Zamindari Abolition Act of 1950, land reform, land survey came successively as post- independence reformations. Nehruvian development was in its track. Parit Porikotha (The Tale of Wasteland) dealt with massive concept of different conflicts. Based in Paranpur Village, where Mother Kosi is meandering with fluid and flood. She is Goddess. Man-nature interplay, ecology in the social, political, and economic realities as subjects. The landscape emerged as a central character. Contexts of the myth of Sunnari Naika, (traditional ballad), reminds folk history of Paranpur’s five water pools. Water conservation or rainwater harvesting as outcome of rural indigenous science to mitigate a famine watering to the village has been proposed.

Gyawali (2017) comments, “In Partī Parikathā, environmentalism and developmentalism are not antithetical; rather, Renu’s concerns lie in the ways in which both are carried out. In fact, it is an amalgamation of the two that is proposed as an alternative to the inadequacies of the post-colonial bureaucratic state at the end of the novel, whereby the developmental state aids Jittan’s efforts to farm the parti, and in doing so, increase fertile land for agriculture. Having established the inseparable links between the local community and ecology throughout the novel, Renu demonstrates that any eco-developmental project is only feasible when it actively involves and benefits the local villagers.”

In protest of police atrocities towards the movement, Renu sustained injuries. A metamorphosis of Renu had emerged, as the conscience of intellectuals.

Renu was in political news of Bihar, at onset of Emergency rule,1975, when he was strongly associated with Jayaprakash Narayan, a leader in the opposition. In protest of police atrocities towards movement Renu sustained injuries. A metamorphosis of Renu had emerged, as the conscience of intellectuals. On November 18, 1974, he renounced his honorary title of Padmashri awarded by President Giri, in 1970, his membership in the National Sahitya Akademi, and a monthly stipend of Rs. 300 from the Bihar government. The eclipse of literature and life took place.

Kathryn Hansen (1982) states, “Two years later Renu was gravely ill, yet he consented to be operated upon only at the conclusion of the electoral campaign against Indira’s Congress. When he heard the news of the J. P. – inspired Janata Party’s triumph at the polls, he went into surgery and never regained consciousness. Despite his failing health, his last years had been spent on the move, from city to city, setting up street-corner poetry readings; in and out of jail, often on hunger strike; across the border to Nepal and back, fleeing the police during the Emergency. His visibility had diminished during those final furtive days, but his death (11/4/1977) brought him a martyr’s acclaim. Here was a writer whose concern for the common man had been translated from words into action.

… he became a hero to the young, a model of commitment to a cause. This last phase of his life completed the process Renu himself so often imposed on others – the conversion of man to legend.

Renu’s literary reputation had been secure before. Now, he became a hero to the young, a model of commitment to a cause. This last phase of his life completed the process Renu himself so often imposed on others – the conversion of man to legend. The author became one of his own characters, and it is no wonder that his eulogisers most frequently cited for comparison one of Renu’s fictional heroes – Bavandas, Hiraman, or Jittan – when they honored his memory.”

References

1. Sadan Jha, Visualising a Region: Phaniswarnath Renu and the archive of the ‘regional–rural’ in the 1950s, The Indian Economic & Social History Review, Volume: 49 issue: 1, 2012 page(s): 1-35

2. Amul Gyawali, Discovering eco-criticism in Hindi: Renu’s Tale of a barren land – Mulosige

3. Kathryn Hansen, Introduction, Journal of South Asian Literature , Summer, Fall 1982, Vol. 17, No. 2, THE WRITINGS OF PHANISHWARNATH RENU (Summer, Fall 1982), pp. 1-4

Visuals by the internet

By

By

By

By

By

By

Well written tribute to the great author!

Purnea is also intimately related to bengali literature and its background..Satinath Bhadury acclaimed writer of Dhorai Charit was from Purnea and both he and Phaniswar carried mutual affinity to their respective creative skill.

Gives an in-depth analysis of the legendary writer.

Thank you so much for sharing. I haven’t heard of him.

Best regards