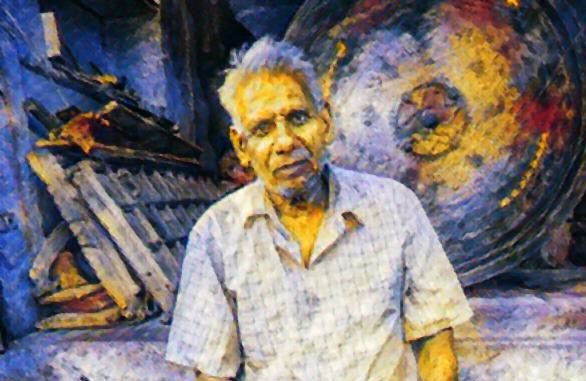

Here’s Abu’s character sketch about Nagen Das, a caretaker, in this short story. An exclusive for Different Truths.

Nagen Das was our caretaker. We added ‘Da’ to his name and lovingly called him Nagen Da. Elderly members of our society, however, called him as Nagen. Aged around fifty, tall, slim, fair, nose sharp, head partly covered with grey hair, duty-bound, Nagen Da was a man of many parts. He was a mechanic and could repair fan, motor, fridge at ease. At times he took one day leave. That day he setup a stall in a village fair. He sold parched nuts, made money, bought dolls and sweet for his grandsons and granddaughters. Next day, again, he joined us. And he always served with a broad smile.

Nagen Das was our caretaker. We added ‘Da’ to his name and lovingly called him Nagen Da. Elderly members of our society, however, called him as Nagen. Aged around fifty, tall, slim, fair, nose sharp, head partly covered with grey hair, duty-bound, Nagen Da was a man of many parts. He was a mechanic and could repair fan, motor, fridge at ease. At times he took one day leave. That day he setup a stall in a village fair. He sold parched nuts, made money, bought dolls and sweet for his grandsons and granddaughters. Next day, again, he joined us. And he always served with a broad smile.

Nagen Da was a man of many parts. He was a mechanic and could repair fan, motor, fridge at ease. At times he took one day leave. That day he setup a stall in a village fair. He sold parched nuts, made money, bought dolls and sweet for his grandsons and granddaughters. Next day, again, he joined us. And he always served with a broad smile.

Before Nagen Da’s appointment we had a harrowing time. People, young, middle aged, elderly were regularly recruited. But a week or two they served, and then suddenly disappeared. Why? We had no idea. Moreover, they could not take care of themselves. How could they take care of fifty people? One day we saw a young boy, who at 10AM was peacefully snoring reclining on his chair placed at the gate of our block. The record book lay idle in the table. Another day, we saw an aged man smoking biri and checking owners and strangers alike. People complained. We called our agency and next day he was relieved. Then again a middle aged widower took care of us. He talked and talked, and had a keen interest in our personal lives. So he was freed. This way, in five years, a hundred men were hired and fired.

Then one day rains went away, the sky became clear and the sun shone. Nagen Da arrived, and within a month we began to depend on him. Working parents were not at home. Nagen Da took the boy or girl home. A flat owner had gone to visit a temple, and the milkman had come. He rang and managed the milk. Letters, papers, magazines, and bills he kept in his custody. And soon he saw us, he handed them over. If a room was locked and a teacher had come he did his best. A cook had come, and nobody was at home, he coughed and cleared the air.

Early morning, his routine was to switch the pump on, to switch the lights of each floor off, to unlock the front gate and the gate of the roof, to welcome a dozen delivery men, sweepers, cooks, maids, and drivers.

Early morning, his routine was to switch the pump on, to switch the lights of each floor off, to unlock the front gate and the gate of the roof, to welcome a dozen delivery men, sweepers, cooks, maids, and drivers. Every morning he cleaned cycles and bikes, and earned some extra money. He greeted us with a ‘good morning’ and we also returned the same with a broad smile.

One evening, I saw Nagen Da spreading some crumpled newspaper in a corner of our garage. The basement was empty. I, two LED bulbs, two lizards on the ceiling, one frog under a car, some cockroaches, and a swarm of mosquitoes were the audience, and Nagen Da was the lone actor.

“Nagen Da, what’s the matter? Why in this hour were you covering the dust with papers while the chairs were empty?” I asked in a bewildered voice.

Nagen Da bashfully smiled while caressing the creased papers.

“It’s pleasant time. Surroundings are quiet. I only want to make it more pleasant,” Nagen Da laughed.

I am confused. Mosquitoes were hovering over heads. They were biting. So I randomly moved my limbs, scratched and walked around the garage.

I am confused. Mosquitoes were hovering over heads. They were biting. So I  randomly moved my limbs, scratched and walked around the garage.

randomly moved my limbs, scratched and walked around the garage.

Minutes later, he came with a set of tablas, boxed in two worn out bags, coated with a thick layer of dust.

“Is it a gift?” I asked with a smile.

Nagen Da looked at me with an expression which did not confirm ‘yes’ or ‘no’. He took a piece of cloth and begins to clean the bags sitting cross-legged on the paper-carpet.

The frog at regular interval came out of the shadow of the car, caught a worm and playfully returned back to the shadow again.

“Nagen da, where is the mosquito coil?” I thumped my legs and asked.

“Finished,” he dully said.

“How? Yesterday I bought it, and you have burnt them all! Not a broken one you save? No, it’s bad,” I vexed.

“Dada, do you know Voju?” indifferently he asked.

“Who is Voju?” I riposted.

The black fellow with yellowish tiger-teeth whom, you, one day, gave a smoke. That angular face, lanky man, who came here every other evening and talked of fishing and fields.

“Why? The black fellow with yellowish tiger-teeth whom, you, one day, gave a smoke. That angular face, lanky man, who came here every other evening and talked of fishing and fields. That fellow was my childhood friend, Voju.”

“So!”

“Dada, he is a caretaker of Shanti Niwas. He asks for a coil and steals the whole packet. Stealing is in his blood. During childhood, he made a name in our neighbourhood, Kurmatuli by stealing. He stole eggs of birds and chickens, marbles, fish, bananas, guavas, mangoes, wood apples and so. On one full moon winter night, he led us to the river bank. He climbed the date trees one by one, and took off the rasa-filled pitchers. We merrily drank and danced that night.” He took the little hammer and began to beat the side strings of the tablas.

I felt elated but feigned that I was not happy with the loss of the coils.

“Dada, It’s not a gift,” Nagen Da clarified. “I have bought them at Rs. 500. I thought I made a bargain,” he beamed.

****

For a fortnight or so Nagen Da lost his cheerfulness. He looked pale and wan. He was no longer a talker. Day and night he sat on his chair, moved lips, looked at the ceiling, and watched the lizards catching worms. Even the known faces smelt odd at his changed ways. Perhaps a loss in the family! Perhaps a quarrel with family members! Perhaps a thought of dowry for daughter’s marriage!

For a fortnight or so Nagen Da lost his cheerfulness. He looked pale and wan. He was no longer a talker. Day and night he sat on his chair, moved lips, looked at the ceiling, and watched the lizards catching worms.

Then one evening, I saw him again sitting on the papers with his tablas. They looked new, and the sound was too good.

“Nagen Da, you have really made a bargain!” I merrily said.

He threw a resigned look and tiredly said, “Playing tabla is my passion from childhood. It’s a disease within. What can be done? I spend on it Rs. 3000 more. For a poor man it is a luxury. Family members, friends, relatives are angry and they’ve stopped speaking to me.”

“They are not fools, I think,” I opined.

Nagen Da slowly measured me from head to toe. His eyes were keen, and apparently there was hatred in his look.

“I’ve taken exception of you. But I am mistaken. You too wear the fur of the earthlings! You have no wings to soar. And happy with your home and hearth!” he rued.

A car entered. Its headlight flashed. Nagen Da sprang up, made passage for it by folding his papers, saluted Dr. Dutta, and when the doctor made his way to the lift, he again spread the papers and sat.

A car entered. Its headlight flashed. Nagen Da sprang up, made passage for it by folding his papers, saluted Dr. Dutta, and when the doctor made his way to the lift, he again spread the papers and sat. And he began to play.

I took a chair and watched him playing. Perhaps he felt uneasy.

“Leave me alone. Go home and watch a reality show. Why do you waste your time here? It’s a useless art and only fit for a useless few!” he lashed.

“I need to go to shop a packet of salt,” I defended.

“Then go. If you are late you’ll lose salt, and have to go empty at night,” he threw a loathing glance at me. Nagen Da looked serious. He briskly hammered the tablas, killed a mosquito, fixed his gaze at the frog for a while, and then began to play again. His face was dry, fingers long and bony. The shadowy, lonely basement was, however, filled with a sonorous air again.

Photo from the Internet

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By