A Diaspora, Dr. Partha shares the agony of a Bengali far away from his homeland. He confesses, there are quite a few other Bengali immigrants both from Bangladesh and West Bengal — highly educated, scholarly and erudite — who are satisfied with the small society they have and therefore do not feel any particular urge to invite outsiders like us. New Jersey or Long Island — where most of these more affluent, educated West Bengalis live — is like a group of islands only connected by long-distance, car-driven highways, creating more distances between people. We do not have the time or desire to go out of New York City to see either a Durga Puja or a Tagore performance and return more depressed that we never felt truly welcome. A Special Feature, for Different Truths.

No, I don’t want to make it sound corny. That’s not the purpose. I truly feel that it could be one last time I get to live on the 25th of Baisakh — Tagore’s birthday — which normally falls on the 8th of May.

This year, just like any other year, much fanfare is happening in West Bengal and Bangladesh, various Bengali neighbourhoods of India, as well as cities across the world wherever there is a community of Bengali people — big or small.

There will be Tagore’s songs. There will be Tagore’s plays. There will be Tagore’s poetry. There will be Tagore’s dances. There will be talks about the poet-philosopher’s poetry and philosophy. More resourceful Bengali communities in places such as Kolkata and Dhaka and London and Toronto will put out special literary publications to observe the special day. Some will try experimental music — using Tagore’s songs. Some will stage Tagore’s famous plays — Post Office, Land of Cards or Red Oleanders from a new, refreshing point of view. Some will perhaps have an exhibition of Tagore’s paintings.

I know here in New York, a group of Bengali musicians and artists is putting together an audiobook of Tagore’s short stories — The Man from Kabul, Return of the Little Boy, The Postmaster — with help from young-generation, college-age Bengali-American boys and girls. Kudos to them.

I have no doubt there’s going to be countless other events, programs and performances all over the world to celebrate this occasion. Especially, Tagore’s 150th birthday was particularly celebratory; it is likely this year many places are perhaps completing their year-long observance with special wrap-up celebrations.

I could not be a part of any of the numerous gatherings — either in America or Bengal. I am not a part of any of the numerous Bengali clubs, societies and organisations — either in America or Bengal. I do not live in India anymore. I live in a Brooklyn neighborhood where there is a small smattering of immigrants from West Bengal; I know once they had an association that held Durga Puja and therefore, perhaps, Tagore Jubilee as well. But I know the group slowly dwindled, some old inhabitants left this unsung corner of New York City and some others went back to India. In any case, we never hear from them.

There is a large Bangladeshi community within walking distance of where we live in Brooklyn. In fact, working as an immigrant rights activist especially among the South Asians, once I had made an estimate that only this community counted about 30,000 people. It is a large community that has associations with many known and unknown districts of Bangladesh; they frequently host their picnics, street fairs and Eid dinners. But I am not sure if they ever hosted any Tagore birthday celebration. I learned from various friends that most of them came from conservative-Muslim areas in Bangladesh where “Hindu-liberal” Rabindranath Tagore was not such a household name. That is not to say all conservative Muslims are anti-Tagore or anti-Hindu.

In some other West Bengali and Bangladeshi communities in New York and New Jersey, there will be programs and performances. But these days, after working with and for especially the Bangladeshi community, it has dawned to me that inviting someone like me who is not from political Bangladesh is not a priority. After living in New York City for so many years, my family and I have accepted the fact that in spite of our desire to belong with a larger, undivided Bengali diaspora, we are not, in any real sense, part of either a “mainstream immigrant” Bangladesh or West Bengal. (Apologies for using an oxymoron.)

Chances are, we will not know if there were Tagore celebrations in New York or New Jersey where my long, post-9/11 activist experience once had an estimate of some two hundred thousand Bengalis — over eighty percent of whom were from Bangladesh. Practically all the weekend Bengali-language parochial schools and practically all of the two dozens of weekly Bengali-language newspapers and magazines operating and publishing out of New York are Bangladeshi.

For a long time, my family and I were actively involved with one of the weekend schools where I taught advanced-level Bengali to just-graduated students, and my family members participated in their cultural programs. For a number of years, especially after 9/11, as an important part of my immigrant rights activism, I wrote columns in a number of Bengali weekly newspapers and magazines — Thikana, Ekhon Samoy, Bangalee, Sangbad, Porshee. Now, I mostly write for Bangladesh’s Sangbad Pratidin.

With the schools and publications alike, I always did what I always do: educate the community about the difference between culture and kitsch, and speak and write about human rights and justice. When I worked professionally for two immigrant advocacy organisations — one in Jackson Heights, New York City and the other in New Jersey, I also worked with Bangladeshi immigrant families who bore the brunt of a terribly unjust and primitive immigration system here in the U.S. Among other activities, I worked with a few men and women who were in prison for a long time for minor immigration violations; I also worked with some others who were spared from prison detention or deportation because of our work.

I have many friends and acquaintances. I built precious connections with journalists, activists, writers, singers, playwrights and music teachers. I always felt proud to have thought I was a member of the larger immigrant Bengal and immigrant South Asia.

Yet, there is a strange disjunct — an insurmountable wall — between me and my family and the societies both in the Bangladeshi and West Bengali community. West Bengali immigrants do not know us well: we live in a not-affluent area in Brooklyn mostly inhabited by African-Americans, Jewish people, Bangladeshis and Pakistanis. Bangladeshi immigrants do not think we are one of them because we came from India — a country they do not know anymore. The conservative-Muslim Bangladeshis (the variety I mentioned above) do not like or understand a liberal-progressive, one-nation Bengal that Tagore and his predecessors from Bengal Renaissance envisioned. The young-generation, liberal-educated Bangladeshis do not know the common history and heritage of two Bengals shared over one thousand years before the British cut the land of Bengal in halves, erecting insurmountable, blood-soaked borders.

Yet, a very large section of Bangladeshi Bengalis (it’s a very strange term, in my opinion) — most are Muslims — are moderate in their religious and social views, avid music, theater and literature lovers, and are the biggest consumers of music and movies from Calcutta and West Bengal — even today. Strangely, however, some of them have a general apathy, indifference, ignorance and often anathema about political West Bengal and India. When they find out I am from India and not from Dhaka, Sylhet or Chittagong, they talk to me differently. Again, I’m not generalising. How can I, when I have so many special friends from Dhaka, Sylhet or Chittagong?

There are quite a few other Bengali immigrants both from Bangladesh and West Bengal — highly educated, scholarly and erudite — who are satisfied with the small society they have and therefore do not feel any particular urge to invite outsiders like us. New Jersey or Long Island — where most of these more affluent, educated West Bengalis live — is like a group of islands only connected by long-distance, car-driven highways, creating more distances between people. We do not have the time or desire to go out of New York City to see either a Durga Puja or a Tagore performance and return more depressed that we never felt truly welcome.

All of the above — the entire, personal, true story I told here — is a slow but sure recipé for death. If I was not a high-energy, activist, never-say-die-type personality who would go out of his way to find new friends, colleagues and communities and stay involved with newer and ever-challenging, creative activities — immigrant movement or labour education or Brooklyn For Peace or Durga Puja or Bengali New Year celebration (or even the Tagore-150 we organised in Manhattan last year with help from New Yorker) — death would have come much faster. In my thirty-plus years of living in the U.S., I have seen a number of people — a few of them being highly talented but decidedly loners — falling victims of this extreme alienation followed by depression, dark diseases and death. I always, always carry that fear deep inside that one day, I’m going to be a victim of a similar alienation and die untimely.

Every year, therefore, at this time when the rest of the world is celebrating the life and work of this incredible genius named Rabindranath Tagore, the question comes to my mind: am I going to live one more year to see the next Tagore birthday celebration? Which song would be the last Tagore song I hear before I die? Which Tagore poem would be the last one I read? Which short story would I translate the last before I perish — and perish prematurely?

I hope I didn’t make you too sad or perturbed and I certainly hope I didn’t make it sound too corny, as if I was trying to draw your sympathy — sympathy for a forlorn soul.

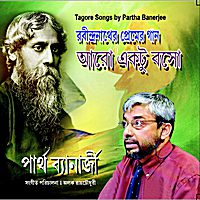

If you feel that way, I am sorry. I do not have anything to offer you to compensate for it — other than the two dozens of Tagore songs I recorded. I also have a few translations of these songs as well as translations of a few Tagore short stories.

I also have a YouTube of one of my talks on culture and Tagore — a talk I gave recently at an Indian university. And if I may say it, I have recently managed to compile a whole host of my essays on Tagore in relation to cultural erosion and globalized kitsch. I’m actually in the middle of writing a book on the above.

I hope you receive these gifts I leave for you and forgive me for my personal, not-so-cheerful rambling.

Celebrate Tagore. He showed us an educated, modern, progressive way to live. He was not a perfect man. In fact, he had many flaws. I do not consider him a God. I consider him a very important, humanist philosopher-poet teacher who taught us human spirituality, universality and peace.

Tagore taught us the message of emancipation: in Bengali, the word is Mukti. It means inner freedom: the liberation of the soul. Nandini showed us the way in Red Oleanders.

If this is the last Tagore birthday before my death, I want to remember him that way.

I hope you get to know him.

We are republishing Dr Partha Banerjee’s article, with the kind permission of the author. ~ Editor

Photos from the author and Internet

#Tagore #CelebrateTagore #BangladeshiBengalis #BangaldeshiCommunityInUs #Immigrants #PoetAndPhilosopher #TributeToTagore #DifferentTruths

By

By

By

By