In this interview with Ashish, Prof Sonjoy Dutta Roy explores the structure of Hayavadana, use of myths and symbols, significance of masks, the underlying theme of the play, among other things. We are republishing it in Different Truths.

Sonjoy Dutta Roy is a Professor in the Department of English and Modern European Languages, University of Allahabad. In 1995-1996, he was a Senior Fulbright Fellow at Louisiana State University Baton Rouge, USA and in 2004, he was a Fulbright Visiting Professor teaching a course on ‘Narratives in India: Poetic Fictive Performative’, at University of California Berkeley, USA. His papers on Poetry and Theatre have been published in several journals in India and the USA. Prominently he has published papers in Yeats Eliot Review, Arkansas and the Journal of Modern Literature, Temple University, Philadelphia. He has delivered talks on Theatre and Literature at JNU, Jadavpur University, Pace University, Tufts University, SUNY Stonybrook. Recently, in 2016 and 2019, he was invited to speak on Theatre in India at the University of Connecticut, Storrs, and at the University of California, Berkeley. He has his own Theatre group called Theatre for Peace, comprising of students, faculty and alumni of the University of Allahabad and over these past two decades, they have performed Hayavadana by Girish Karnad, Dak Ghar by Rabindranath Tagore, Autobiography (Atmakatha) by Mahesh Elkunchwar, One Day in Ashadh (Ashadh ka ek Din) by Mohan Rakesh, Mahesh Dattani’s Tara, Arun Mukherjee’s Mareech, the Legend, and Badal Sircar’s Evam Indrajit among many other plays. At present, he is the Coordinator of the Centre for Film and Theatre, University of Allahabad.

In this interview, Ashish asked several questions on Hayavadana related to the structure of the play, its use of myths and symbols, the significance of masks, the underlying theme of the play, its contemporary relevance, psychological aspects, and the quest for completeness, the significance of Lord Ganesh and Goddess Kali, etc. to bring out the implicit and deeply layered meanings through the lens of a theatre person, Sonjoy.

Ashish: What do you think about the way the play Hayavadana has been structured?

Prof. Sonjoy: We must not forget that when Hayavadan was written and performed, it pioneered the use of folk theatre in a way that would appeal to the understanding of a modern urban audience watching it on a proscenium stage. Storytelling and folklore have always been a part of our rich narrative tradition in India. But the urban population had long been alienated from its own rich traditions, mainly because of the Western orientation of our mainstream education system and its westernised focus and emphasis. Our Indian theatrical traditions, too, had been eclipsed by the dominance of Western theatre in Colonial times. Post-independence, the focus shifted towards indigenous traditions in art and culture. Hayavadana today can be recognised as a milestone in this major shift of focus.

A play is not written to be read but scripted for performance. To create this parallel between myth and the contemporary Karnad uses a narrator Bhagwat who is a storyteller as well as a director of a performance narrative. By this device, it is easy for Karnad to move from oral narration to the performance of that story. There is a frame story that moves into and frames the main story. The frame story is the mythical base or foundation for the main story which is a more modern tale exploring the socio-psychological symbolism and significance of the folklore and myth of the frame story. This kind of structuring is very much a part of the Shrinkhala narrative tradition of Indian storytelling. The Kathasaritasagar (from where the Vikram Vetala story is picked up), The Jataka, the Panchatantra, followed the shrinkhala tradition. One story flowed into the next with a subtle shift of perspective. Stories moved from generation to generation renewing themselves with the changing socio-political and psychological contexts.

Ashish: How substantial is the implementation and utilisation of myths and symbols in Hayavadana?

Prof. Sonjoy: There is a genesis myth in the Frame story, which is the story of the Princess, the Gandharva, the curse of Kuber, the marriage of a woman with a horse and the birth of Hayavadanaand his peculiar dilemma. Girish Karnad picked up this Kannada folktale, most probably from poet collector AK Ramanujan during his Fulbright stint in Chicago. This genesis myth symbolically highlights the uniqueness of the human situation and its origin. Born as a cross between an animal and a Gandharva, we as humans, as exemplified by the symbolism of the Hayavadana figure, are neither fully Gandharva, nor fully animal. Had we been fully Gandharva, we would have been spiritual beings, free of animalistic desires. Had we been pure animals, we would have been totally happy leading an instinctive animalistic physical life without being disturbed by intellectual or spiritual notions of ourselves. As humans, like the Hayavadanasymbol, we are caught between the animalistic physical pulls on the one hand and the spiritual Gandharva pulls on the other hand. This creates a sense of inherent identity crisis and a sense of incompleteness that troubles us as humans. The Gandharva, Hayavadana’s father, is complete in himself as a spiritual being. The mother chooses to become a horse, thus symbolically identifying with the animalistic. She thus becomes a symbol of the animalistic which again is complete in its animalism. It is their child Hayavadana, who is in the in-between, incomplete state, who symbolises the human state.

Ashish: Is the rampant caste system in India brought under scrutiny in Hayavadana?

Prof. Sonjoy: The Vikram Vetala tale picked up from Kathasaritasagar brings to scrutiny the rampant caste system prevalent in India. The symbolism embedded in our folk tales makes them open to multiple interpretations. Often, a later interpretation can totally invert an earlier interpretation. Karnad has expressed that it is possible to make an earlier interpretation do a headstand, through a later interpretation. He literally does that to the Kathasaritsagar story in his play Hayavadana. In the earlier story after the heads get interchanged, there is no problem in attributing identity. The head would determine who was Kapil and who was Devadutt. But this is problematised in the play Hayavadana. In the Indian caste system, the head symbolises the intellect and culture and thus gets associated with the upper Brahmin caste. Devadutt belonged to the upper caste. Identifying a person by the head benefitted Devadutt and the upper caste Brahmins. The lower parts of the body were identified with the lower castes. Kapil belonged to the lower caste. He was the loser when Padmini goes off with Devadutt’s head on Kapil’s body. This caste orientation gets challenged in the play. The importance of the lower castes, the lower parts of the body, physicality and sexuality is asserted in the play. The body is associated with the natural and biological. The head is associated with culture and civilisation in human advancement. But Karnad’s Hayavadana asserts the importance of biology and nature in the completeness of the human identity. It points out the fault lines in our cultural and civilisational advancement.

We can notice how myths, folklore and our ancient traditional stories are capable of symbolically showing us our deepest truths and also tell us where we have gone wrong. This can happen only when a playwright like Karnad is able to reveal hidden layers of meaning in the symbols contained in these tales and myths.

Ashish: How important and crucial is the use of masks in the play Hayavadana?

Prof. Sonjoy: Karnad has disclosed that the use of masks in Hayavadana resulted out of a discussion on masks and their significance between him and BV Karanth (of the Madhya Pradesh Rang Mandal). Masks have a double significance. a.) They can be used tohide (or mask) the true face. b.) They can be used to highlight certain aspects of the self. In Hayavadana, we notice both the uses. Theatre often demands innovations. This demand must have been felt when the heads had to be cut and replaced on different bodies. When we were performing Hayavadana, we wondered how this could be done. In a flash, the idea of masks solved the problem. Right from the beginning, we made Devadutt wear a white mask and Kapil wear a black mask. We made Devadutt wear a white dhoti and kurta and we made Kapil wear a black dhoti and kurta. The mask and the attire highlighted their character on the one hand. On the other hand, they hid their real faces from the audience. In the Kali temple, it is dark and in the darkness after cutting their heads (in acting), they quietly take off their masks. When Padmini is supposed to put their heads back, she quietly gives Kapil the white mask and gives Devadutt the black mask. They wear these changed masks without the audience realising it, because of the darkness. When they get up after becoming alive again, the audience sees a black attired Kapil with a white mask and a white attired Devadutt with a black mask. The identity crisis is perfectly expressed through this subtle use and change of masks. Karnad, as a theatre practitioner, and not just a writer of plays, knew these practical dimensions of theatre and used his practical knowledge, as Yakshagana and Folk theatre demanded.

Ashish: Girish Karnad used masks for Kapila and Devadutta but not for Padmini. What may be the reasons behind it?

Prof. Sonjoy: Padmini, according to the suggestion of her name, is the lotus woman of Vatsayan’s Kamasutra. A lotus woman is a symbol of womanly perfection. Why would such a woman require a mask? A mask, as we saw, was required to reveal the schism in personality, its fragmentation, and incompleteness. Both Devadutt and Kapil were imperfect and incomplete. It is through them that this saga of human imperfection finds its symbolic expression. Padmini, is a perfect feminine ideal, seeking perfection and completeness in her relationship with the male. Woman, as prakriti, as nature, has been symbolically seen as perfect and complete. Males, as part of patriarchy, have created the body head separation and the entire moral fibre of society that condemns the body lowers its status and valorises the head, the intellect. Thus, Padmini does not require masks, whereas Devadutt and Kapil do.

Ashish: Do you think this play is a kind of mockery as for the way Lord Ganesha and Goddess Kali have been represented?

Prof. Sonjoy: No. It is not a mockery at all. Let us not forget that the robust folk imagination was quite capable of humorously imagining their Gods. The sanctity and sacredness of the Gods are not diminished by this sense of humour. In fact, it humanises the Gods and brings them closer to us. That is the beauty of the folk imagination. Our myths and epics, let us not forget, were created out of this same folk imagination. It was later that we sanctified the Gods and created Apocrypha. In doing it, we lost our sense of humour regarding our Gods.

Kali is the dark Goddess, symbolic of the unconscious mind, subconscious desires, the Id as Freud called it. These desires are more often than not morally unsanctioned in society. Padmini’s desire for Kapil would be considered an immoral desire and condemned. Only Kali, the Dark Goddess, can value its natural and instinctive truth. Thus, when Padmini mistakenly makes a Freudian slip by putting Devadutt’s head on Kapil’s body she unconsciously gets her perfect and complete man. Kali recognises the pure honesty of the act (an honesty that Padmini could never have consciously acknowledged) and sanctifies it. Karnad is able to envision Kali in a way that makes her a unique concept of Godhead.

In a pantheon of perfect Gods, Ganesh is the only God, who personifies imperfection. Potbellied, with a broken tusk and the head of an elephant he is in stark symbolic contrast to the other Gods and Goddesses. Can the perfect Gods ever understand or empathise with human imperfection? Ganesh is the only God who can understand human imperfection because he is imperfection incarnate. Karnad’s use of Ganesh thus should not be taken at the level of mere worship for an auspicious beginning of an event (which is what Ganesh puja usually signifies). Gajavadan, symbolically connects straight to Hayavadana and his situation, and by extension to the imperfect human situation caught between the animalistic and the Gandharva mix-up that I explicated in the genesis story myth.

Ashish: I think Hayavadana is a play depicting the quest for completeness. What is your opinion?

Prof. Sonjoy: Of course, it is a play depicting the human quest for completeness. But it is important to understand how Karnad subtly weaves the answer into the structure of the play. In the end Padmini leaves her child with Bhagwat. She tells Bhagwat that he should take the child to the tribals who were so close to Kapil’s heart. The child would learn to live in the forest, run, hunt, climb trees, swim in the river and lead a natural biological existence as his foundational growth. Later he should be taken to the Brahmin Vidyasagar to be educated and cultured and develop his intellect and spirituality. Thus, unlike Kapil or Devadutt, who were both incomplete and imperfect, the child will develop into a complete and perfect man.

Ashish: Is the play feminist in nature? If so, to what extent feminism is successful in breaking the patriarchal norms established through Hayavadana? Do you trust that Karnad’s plays like Hayavadana, and Nagmandala advocate the theme of adultery?

Prof. Sonjoy: I do not think that Karnad had either feminism or antifeminism in mind when he scripted Hayavadana. In fact, he had a vision of feminine sexuality that he wanted to explore. He does it in Hayavadana and Nagamandala. Folklore and folk theatre, has that robust symbolism that is capable of subtly exposing certain taboos and societal moral restrictions that patriarchy heaps on women’s sexuality. If anything, these plays are liberating for women and critical of the moral fibre of a lopsided male-oriented system of thinking. Thus, I disagree with the notion that Hayavadana as a play has feminist, antifeminist views, or it propagates patriarchal notions in society.

It is a bold exploration of feminine sexuality and therefore liberating for women. Padmini breaks out of patriarchal shackles when she explores her sexual attraction for Kapil. The laws of adultery would be seen as part of these patriarchal shackles. The duality inherent in adultery as a patriarchal shackle is fully explored in Nagamandala, where the husband of Rani freely indulges in an extramarital relationship, but keeps his wife Rani locked up in the house when he goes out. Interestingly, it is a folk tale that is able to symbolically liberate Rani from her prison. Her nightly trysts with the naga who comes to her in the shape of her husband is an extramarital relationship that makes her fully realise her sexuality as a woman.

Thus, I see Karnad as using the symbolism of folk theatre and folklore to explore the subject of feminine sexuality which is a taboo subject in Indian society. The plays thus symbolically liberate women from patriarchal shackles and open the path of feminine exploration of sexuality.

Ashish: How Hayavadana is relevant to our contemporary society?

Prof. Sonjoy: I think the themes of feminine sexuality and the theme of human incompleteness are important themes for contemporary society. They need to be understood in the light of the ways in which Karnad does it in his plays. Correlating myth and contemporaneity is not an easy task. T.S. Eliot talked of the mythical method where modern psychology corresponds with ethnology. He employed it in The Waste Land as did James Joyce in Ulysses. In theatre, Bertolt Brecht uses it in his ‘Epic Theatre.’ But he does it with a political purpose. Karnad’s Hayavadana is structured around this parallel between myth and contemporaneity, but with a socio-psychological orientation. The play has been written by Karnad with such an emphasis and orientation. I feel that it is now an important milestone in the history of Theatre in India because of these factors and features.

Ashish: Girish Karnad has structured this play to run parallel on a psychological level. How successful is he in doing so?

Prof. Sonjoy: The use of Kali to explore the subconscious desires of Padmini is an exploration of the concept of Id of Sigmund Freud. The Id is defined by Freud as a cauldron of seething excitement which is beyond the control of the conscious mind or ego. Thus, it is repressed by moral forces created by society in the form of what Freud recognises as the superego. The human ego mediates between these two forces, the Id and the Superego. We actually see this happening through the character of Padmini. The battle between the natural/ biological and the civilisational/ cultural is also a psychological battle that is a manifestation of the Id/Superego clash. Myths and Folklore symbolically have these psychological moorings. It is for Karnad or T.S Eliot to discover the connections between psychology and ethnology as Eliot does in The Waste Land and as Karnad does in Hayavadana and Nagamandala.

Ashish: What is the significance of the half curtains, dolls and bullock cart, etc?

Prof. Sonjoy: Karnad uses the half curtains used in Yakshagana very creatively in Hayavadana. We must not forget that Folk theatre is performed in open spaces. The proscenium stage is open to the audience only in the front portion, but the village field is open all around. The proscenium stage has a curtain in front that can block the actors from the audience whenever required. This cannot be done in the open arena. The half curtain is a device that is used to hide an actor from the audience. Hayavadana, when he first arrives, has to be hidden from the audience to create a sense of mystery and shock. Two actors carry the half curtain while the actor playing Hayavadana hides behind it. Then slowly the actors lower the curtain and Hayavadangets revealed part by part, creating a magical effect on the rural audience.

We used a half curtain even for the bullock cart scene. A life-size bullock cart was painted on a half curtain and Kapil Davadutt and Padmini, with their upper torsos above the curtain move with the curtain at bullock cart pace, their bodies swaying and emulating the body movement while sitting on a bullock cart. We got this idea from Karnad and from B.V Karanth’s production of the play.

Puppet theatre is prevalent as part of rural culture in several parts of India. Rajasthan has popular puppet theatre where life-size dolls are maneuvered and moved synchronised with dialogues delivered from behind a half curtain. Karnad’s fabulous use of dolls in Hayavadana needs to be mentioned here. Using actors as dolls dressed in traditional Rajasthani attire, we made them move stiffly like dolls and dance and sing. In the play they were used to reveal the passage of time, and the subtle changes in Padmini’s mind and the physical changes in Devadutt and Kapil. The dolls are able to enter into Padmini’ mind and discuss the changes happening there. She dreams of another man, another body, not that of her husband Devadutt. This body is the hard muscular body of a labourer. The dolls also tell us that Devadutt earlier had the rough calloused hands of a labourer when he touched them. The audience knew that these were the hands of Kapil’s body, though the head was of Devadutt. But over a period of time, Devadutt stopped physical exercises, went back to his books. His belly softened, and a paunch made its appearance and his hands have also become soft. The dolls make fun of him and wonder if he is pregnant.

This is a remarkable blend of Puppet theatre and folk theatre, and has the robust bawdy humour that was natural to folk theatre. Girish Karnad’s signature theatre gets established through such significant experiments with folk theatre. For the urban audience, all this was new and exotic and revelatory.

Ashish: Bhagavata is considered the mouthpiece of Karnad, and he expresses his view satirically. What do you think?

Prof. Sonjoy: The use of the narrator, Bhagwat, is also typical of folk theatre. Folk theatre, we must not forget, emerges from the act of storytelling. Storytelling requires a storyteller. The creation of Bhagwat thus is from this figure of a storyteller. Karnad adds another dimension to the persona of the storyteller. That is the dimension of the director of a natakmandali. He has a troupe of actors at his command, who are willing to act out and perform the story that is being told by the director. The director in theatre is an authoritative and commanding figure who is able to move the play in a direction that he or she wants. It is Bhagwat who structures and formulates the movement of the play. Through this structurisation and formulation, the story moves in a guided direction. Out of this guided movement, the messages, and ideas to be communicated to the audience get clearly expressed. I have already talked of the ideas regarding female sexuality and the incompleteness of the human situation as well as the critique of the caste system that the play effectively communicates. Whose ideas are these? Of course, they are Karnad’s ideas. The Bhagwat is used as a mouthpiece as well as a technique for creating a sense of objective distancing.

Ashish: Any particular incident associated with the theatrical journey that you want to share with us.

Prof. Sonjoy: Finally, I would like to share a word about my journey with Karnad’s Hayavadana. I introduced Hayavadana as part of our undergraduate course as my Post-Colonial rebellion against a heavily British Literature loaded English Literature course. I directed the play with BA-3 students again as a rebellion against the English Department Shakespearian orientation. The best way was to choose a robust folk Theatre production and do it in English. It was some job to have a live chorus sing the songs in English. Karnad’s own translations were prose translations without rhyme or metrical rhythm. We changed these translations with permission from Karnad and introduced rhyme and metrical rhythm successfully. Today, it feels good to share this history with all of you.

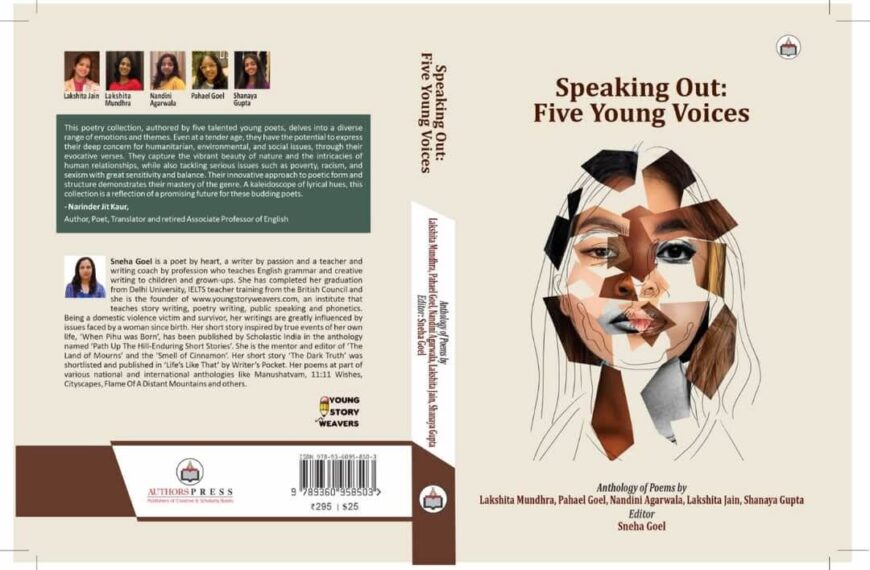

This interview is a chapter in the book, Art and Aesthetics of Modern Mythopoeia: Literatures, Myths and Revisionism Vol-One, edited by Ashish Kumar Gupta and Ritushree Sengupta. We are republishing it with the permission of the author and one of the editors, Ashish.

Photos sourced from Prof Sonjoy

By

By

By

By

By

By