Madhuri travels within to pay tribute to her grandma, who had a formidable and cherished presence in her life, a woman of many talents and boundless love – an exclusive for Different Truths.

My Thama (grandma) was a monolithic and insurmountable keeper of my life, my strongest influence and cheerleader and I was ravenous for her love. On July 4, 1990, she excused herself from the sadness and revelries of the world, in my arms after three years battle with lung cancer.

Thama was born in Benares, around the time of World War I. She had an English governess and attended school till standard tenth. She married my grandfather Amal Chatterjee at a young age and her life then revolved around her family and domestic chores. However, every kind of crisis was resolved by her fine balance between diplomacy and love. Even as a grandmother, she was always tactful and astute, but partial to me. She would stand stubborn to reclaim what rightly belonged to her and always emphasised educational skills that women often deny themselves.

I always remember Thama as an Epicurean soul, fond of music, card games, chess, singing, and books …

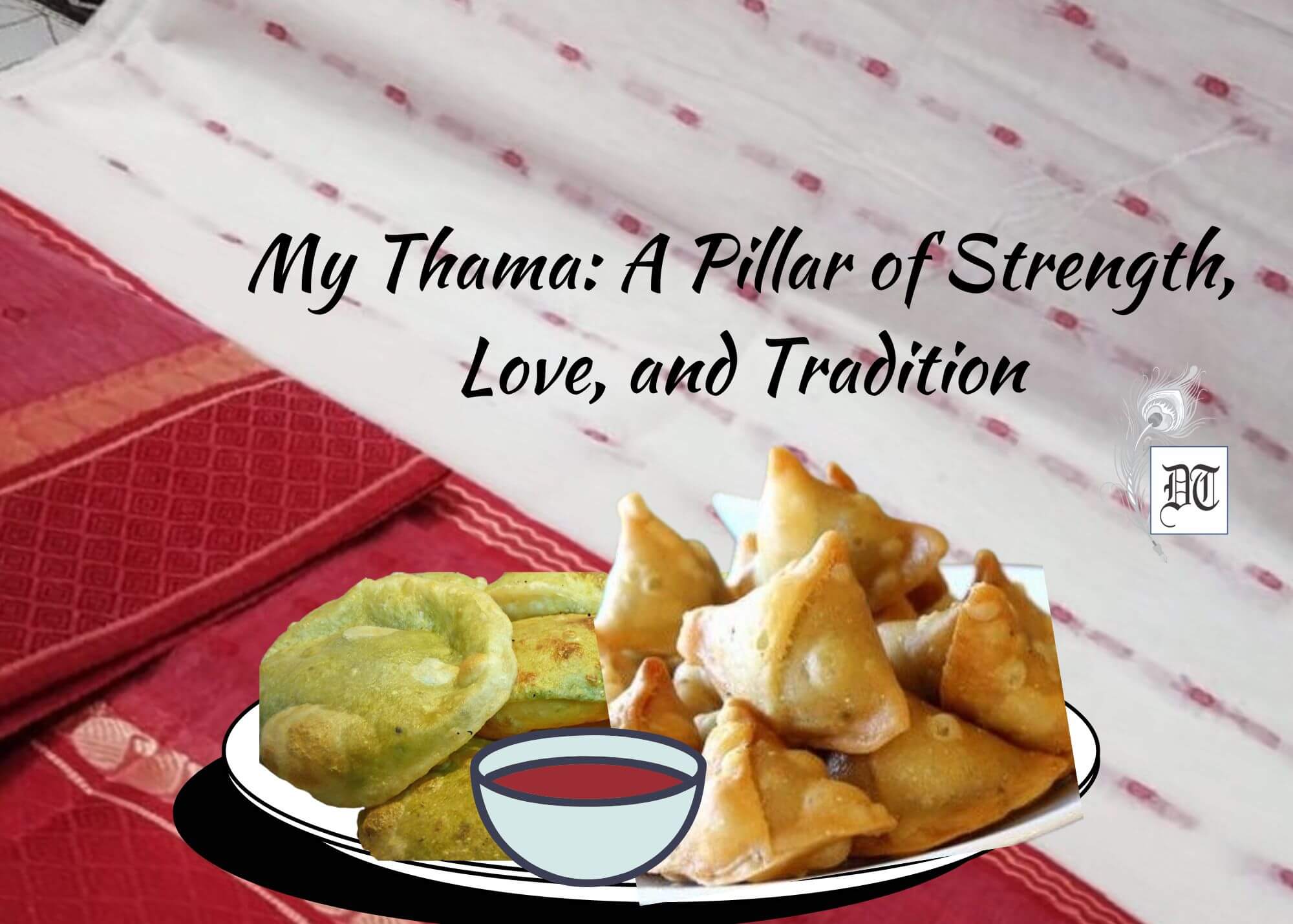

“People don’t die but worlds die with them,” said some wise man. I always remember Thama as an Epicurean soul, fond of music, card games, chess, singing, and books – the things she taught me too. She was passionate about preserving the traditional culinary delights of Bengal. She would create the aromatic universe of potol er dolma, motoshuttir kochuri, taal paturi, phool-kopir shingara to name a few. Thama stood testimony to cherishing companionship through food and adda. Winters would incite a flurry of excitement in Thama as her son and daughters (pishis and kaku) would come and she would not wait to make crisp kochuris with the first green peas of the season. Unworried about her knee pain or backache she would deliver them herself on their plate. Or make Pithe, with Ma and pishis all extending a helping hand.

My childhood perception of Thama matured into understanding her as a woman, a human being, complete with fortes and foibles. She was literate, a good draftsman, a singer, an excellent debater, nurse, yet ambitious and committed to a life beyond the kitchen. She revelled in singing, card playing, contributing to household work, and living each role to the fullest. We would gather at her feet to hear Bangla stories and she would generate each one with age-old foibles, idioms, and fart jokes. She was the first one to introduce me to the world of Tagore, Sarat Chandra and Ashapurna Debi.

Sometimes I wonder if our traditional understanding of feminism would be fluid enough to accommodate a lively person like Thama.

Sometimes I wonder if our traditional understanding of feminism would be fluid enough to accommodate a lively person like Thama. Here was a lady who almost brought up her four kids in the absence of her husband from the age of 26 (Dadu, an engineer and polyglot left his job to join the freedom struggle). She helped each child to complete their basic education and find a career of their own, going with them to different cities, till they settled down. Her entire joint family loved her, and she was endearingly addressed as Sejo. She read newspapers every day, listened to radio and gramophone, read novels, watched soapy serials, never wearing an ornament, and adapted to a white muslin saree with a narrow border. She ensured that both her daughters received educational degrees to have financial freedom. Back then, Thama never hesitated to step out, travel by bus or train, addressing educated officials. There was strict instruction to daughters-in-law to never cover their heads. She treated her sons-in-law like sons pampering them yet critiquing them if they failed.

I have not seen her get carried away emotionally, though she deeply cared for people. She maintained a practical, objective relationship of support and friendship with relatives. She was also the beloved and supreme leader of the family and neighbourhood; she courageously brought out her children from difficult financial times. She could call out to anyone and get the job done and they would be precious in her memory to get a favour in return.

Once I asked Thama if she regretted anything in life, she expressed, not having had a career: “Shobe holo, shuddhu chakri kora holo na” (did all except a job) and she never insisted I do any household chores. “J alpona dite janey shey ghor nikote jaane,” (One who draws alpona knows how to manage a home). She drilled into me a sense of economic freedom, which always stood by me. She only had one weakness, me.

She always remained resolute and strong but turned feeble when her body started diminishing with cancer.

In all my twenty-five years, I received serious disapproval and bashing from her once, when I went to show a completely unknown person some strange destination kilometers away without informing the family. She always remained resolute and strong but turned feeble when her body started diminishing with cancer. She never aspired to achieve the image of a superwoman or feminist, yet she was one in her way. Thama left me like a silent mountain dew, and she would be remembered like a strong, generous bird in a storm. “I want to keep doing what is right without worrying about any opinions,” she often said.

We all loved her unapologetically.

Photos by the author and Picture design by Anumita Roy

By

By

By

By

By

By

It is humbling to have been invited to share this noble lady’s rich life: you are fortunate to have been her granddaughter, and in the writing, you have ennobled yourself.