Journalist and poet, Menka Shivdasani, looks back at her life and times, spanning four decades. While journalism is a voyage without, poetry is a voyage within. In a candid interview with Urna, she speaks about several issues. An exclusive for Different Truths.

Menka Shivdasani’s journalistic oeuvre, spanning four decades, cannot be pigeonholed into stifling boxes. Her stunning, inventive, thought-provoking, transportive poetry cannot be steamrolled into predictable genres. And her lucid, elegantly chiselled, stand-alone voice cannot be contained in a book or two.

For she is larger than the sum of her multifaceted parts and her many talents. And she will always rise like the sun, high above the many lives she has lived and continues to live, on her orange-flecked, blazing wings of fire.

Come, join me, as I get to know her up close and personal.

Urna: I first read your third book, Safe House. I remember running to you, amidst a sea of people, to get my copy signed. Safe House sits elegantly perched amidst my prized poetry collection. Please tell us about your first book, Nirvana at Ten Rupees. And in the words of the critic Bruce King, “one of the best first books of poetry…”.

Menka: My first book appeared in 1990 and contained poems that I had whittled down over more than a decade. It contained 31 poems, some of which went back to the time when I was sixteen – among them, Crystal and Hinges. Nissim Ezekiel, who had been a mentor from the time I left school, helped me put together the manuscript. For some years before that, he had been asking me why I wasn’t thinking about a book, and I had told him I wasn’t ready. He was surprised, because he said young people were always in a hurry to publish, even if they had just been writing for just a year or two. So, when I finally told him, “I think I can do this now”, he laughed, clapped his hands, and said, “So she’s finally ready! Let’s get on with it.”

This was a time before computers, so working on a manuscript involved taking painstakingly typed pages and physically shuffling them into the right order. Along the way, I rejected many poems, such as Sarcophagus, which I eventually included in a later collection.

Word went around that I had a manuscript, though I had not decided on which publisher to approach. Several people suggested Writers’ Workshop, which was the go-to publisher at the time, with beautifully bound books. However, I did not think Writer’s Workshop would be the right choice for me.

One evening, I was walking down Cuffe Parade when I ran into Adil Jussawalla. In my early days as a journalist, I had interviewed Adil and he had told me that young people ruined his pleasure at seeing new books of poetry, by insisting on showing him their manuscripts. I had made a mental note never to do this. So, I simply greeted him and went on my way. He turned back, stopped me, and said, “I believe you have a manuscript. Can I see it?” I had just that one precious typewritten copy, which I gave him, and did not hear from him for a month. Eventually, I called, and he told me about a new publishing house called XAL-Praxis and said he would like to publish it if I were willing. Of course, I said yes at once!

Nissim later told me that he had been intending to ask me for my poems for the Rupa poetry series he was to bring out. There was also a bit of awkwardness over the fact that Dom Moraes asked for my poems for an anthology, and I sent him the same ones, thinking by “anthology” he meant three poems and 20 poets. It turned out he meant three poets and 20 poems instead, which would have meant almost my entire collection! This was meant to be with a large, established publishing house.

Adil learned of this, and told me he wasn’t hurt (his expression belied the words); that I was free to give the poems to Dom. When Dom’s offer fell through, Adil told me he would still be willing to publish my work. For me, it was an important moment, and I have always been grateful that this is how it eventually turned out. Adil took personal efforts to share copies of the book with other poets, and Jayanta Mahapatra was among those who did a wonderful review! I only wish I had taken Adil’s advice and called the book Stet, as he had suggested, but I tried to make up for this with my second collection.

Today, when I speak to young people, I tell them to take care with their first books, because it can make or break their reputations and will haunt them for the rest of their lives.

Urna: I have often heard you talk about Nissim Ezekiel and how he taught you about the art and craft of writing poetry. Do take us down this memory lane and tell us how he mentored, shaped, moulded and impacted your writing.

Menka: I have already said a few things in my response to your earlier question! I have also written about this in The Daily Star, Bangladesh (http://archive.thedailystar.net/2004/01/24/d401242102108.htm).

I first went to Nissim soon after my ICSE exam, clutching a letter of introduction from Patanjali Sethi, the then Training Officer of The Times of India, whom I had had the good fortune to meet. We had, of course, studied The Night of the Scorpion in school, a poem that Nissim grew to hate because people only identified him with this. As I have said in The Daily Star article, Nissim impressed upon me the importance of typing my work in order to judge how the line breaks worked; he spoke of the need to perfect one’s craft while one was young, so that it could be internalised before one could get on with the real business of writing poetry. “Forget about the grand philosophies of poetry,” he said. “First get the grammar right!”

While the journalist Rajika Kirpalani (who died of a brain haemorrhage at age 26) was the first to get my verses published when I was eight years old, it was Nissim who published some of my first “mature” poems around the time I was 16 or 17. There was a handwritten poem I found while cleaning out my bookshelf, which I did not recall writing, and which made no sense to me. This was the poem Today’s Fairy Tale. I typed it out, as Nissim had taught me to do, and it still seemed strange to my eyes. So, I showed it to him and asked what he thought. Nissim read it carefully, and after a long pause, he said, “It is when you show me poems like this that I know that every minute I spend talking to you about poetry is worth my time.” Nissim had always been understated in his praise, and this was the biggest compliment he had ever paid me!

Nissim then had it published in The Times of India with an illustration. Later, I discovered that someone had translated it into Gujarati, and written an essay on it for a literary magazine in that language. It was the first time someone had ever translated my work.

Nissim and I met regularly, once a week, on Wednesdays at 10 a.m. for many years and I was very prolific then, so I always had something new to show him. Once, when we hadn’t ended a meeting by confirming the next one, I did not go to the PEN office the following week. Nissim called to ask where I was, and said, “So what if we hadn’t confirmed it; this time is reserved for you”.

Urna: You just don’t write poetry, you work for poetry, as well. Your efforts are tireless, unrelenting, inspiring. In 1986, you played a pivotal role in founding the Poetry Circle in Mumbai. And since 2012, you have been the Mumbai coordinator for the global movement, 100 Thousand Poets for Change. How was this experience?

Menka: At the time when we formed the Poetry Circle, there were very few outlets for poets to share their work. The Indian PEN published poetry, and there was Kavi magazine in Mumbai, in which Santan Rodrigues played a pivotal role. While some of us were fortunate to find mentors, there were no formal creative writing courses, and certainly there was no Internet.

Nitin Mukadam, a former Economics professor of mine at Jai Hind College, who later became a friend, called to say that he knew someone (Akil Contractor) who had published a book of poems and was wondering if there were other people interested in poetry. Nitin, who had by then moved on to an advertising agency, stressed the value of creating an organisation with logos and letterheads, in order to be taken seriously. In those pre-computer days, such things were not so easy to do. It was a perfect partnership – Nitin had the concept, Akil, through his book, gave us the motivation, and I knew most of the poets.

When we had our first meeting at the Gannon Dunkerley conference hall, where Nitin was the CEO, there was no standing room! I’ve heard it being said that we broke barriers, by bringing together people from different professions – for instance, Marilyn Noronha was a banker, Prabhanjan Mishra was a Customs officer and T.R. Joy was a professor. There were also some students, who have now become very well-known writers today.

Menka Shivdasani with Adil and Veronik Jussawalla

At a SPARROW conference in Kashid, 2006

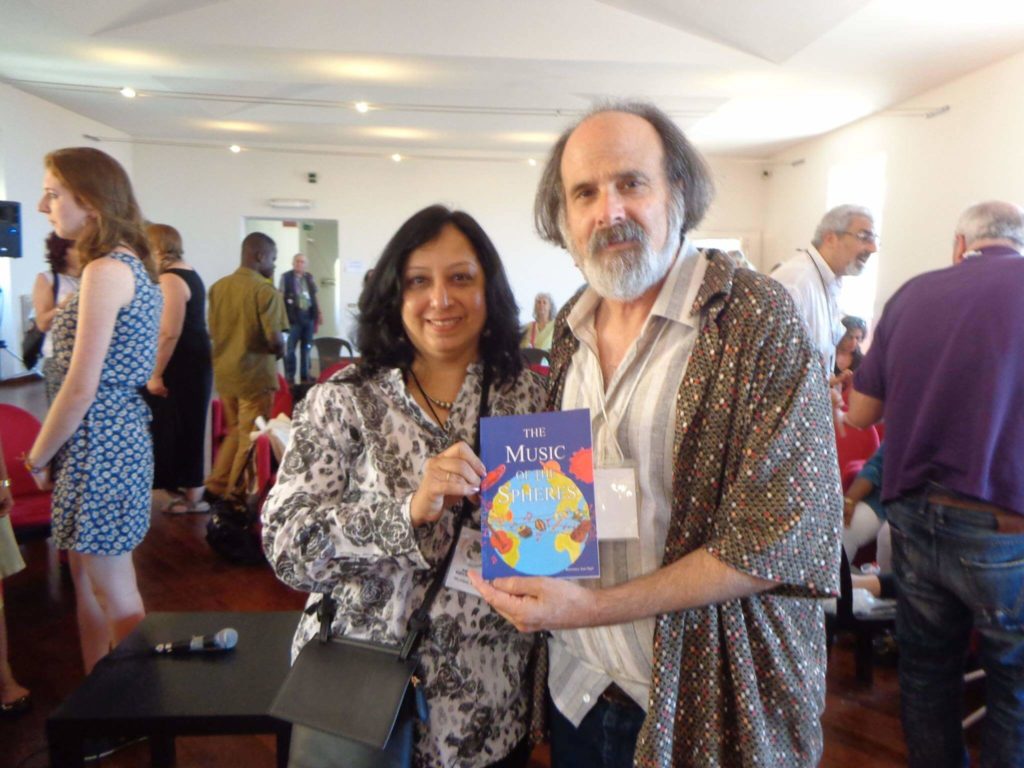

Michael Rothenberg, co founde, 100 TPC with the Music of the Spheres

Many people contributed to the Circle, and through all its ups and downs, it survived for close to two decades. In addition to sharing our own poems for feedback, we invited visiting writers to do readings and conduct workshops. We also instituted a short-lived poetry award with prize money that we contributed through personal funds; in the insular city of a pre-Internet world, I remember an entry coming in from Dubai.

Dom Moraes came out of a 17-year hibernation for our first reading at Cama Hall, and Kamala Das came to Bombay for our first anniversary. We had no money, but somehow magic happened! I have written about this in another Daily Star column. ( https://archive.thedailystar.net/2005/12/31/d512312102104.htm).

In 1988, India Today wrote an article in which it said, “The Poetry Circle, with similar groups in cities across the country, is the most visible symbol of a new revival of Indian poetry in English, sweeping the literary scene.” I found a copy of this online[1] recently.

In 2010-11, a poet named Michael Rothenberg, whom I had never heard of before, wrote to me out of the blue asking if I would be interested in organising an event in Mumbai, which would be part of a global movement based on peace, justice, and sustainability. I personally did not believe in activism through poetry and have never written poems with an agenda. But I did think it was important to nurture poetry through all the platforms possible, and I recognised that poetry can be a catalyst for change, simply because poets feel strongly about situations that impact the world.

In the first year, Anju Makhija joined me – we had already been doing several cultural events for the Press Club under the Culture Beat banner, which lasted for well over a decade. Together, we organised a multilingual reading for 100 Thousand Poets for Change at the Press Club, and a workshop for tribal children through a village school with which she was involved.

The next year, 2012, I approached Kitab Khana with the intention of doing one event on women’s writing; they were so excited by the concept of 100 Thousand Poets for Change that I suddenly found myself – in the space of three weeks – organising five events, held on consecutive days. This has now come down to a more manageable two or three programmes, and my last two festivals were held online. In 2021, we marked the tenth anniversary of 100TPC at Kitab Khana, though it has been 11 years totally if we include the events, we had in 2011.

Again, though I may have been the catalyst, it is only possible to put together such programmes when others are involved, and many people, too numerous to name here, have contributed to the success of 100TPC – among them Vibha Rani, Anjali Purohit, Smita Sahay, Smeetha Bhoumik – and organisations such as NSPA, Poetrywala, SPARROW, Laadli and most recently, SPROUTs, with whom I have partnered. Since I see this as Mumbai’s response to a global movement, I have tried to include as many people as possible, and as many languages as I can. Amrita Somaiya and her team at Kitab Khana have been absolutely marvellous.

The one event that has stayed constant, and has become a highlight, is the programme we do with school children, where we ask them to write poems on particular themes related to 100TPC tenets. Mrs Rati Dady Wadia, former Principal of Queen Mary School, spearheaded this, and Katie Bagli, the well-known children’s writer, soon became a key member of the team.

I guess I have played a small role in building communities, though I have always essentially felt like an outsider. These connections take on their own momentum and create bonds that can last a lifetime. Of course, there are always challenges, but one has to keep working.

Urna: Tell us about your four-decade long career as a journalist and columnist, including a stint with the South China Morning Post in Hong Kong, columns for Hindu Business Line and The Pioneer, and articles in The Times of India and Readers’ Digest. Did the poetry fire feed the journalistic fire, or vice versa? Tell us how did you manage to do so much and hold it all together?

Menka: If I had to do it all over again, would I have chosen the same path? I’m not sure. When I was eight years old and writing verse, I saw the journal called ‘Hi’ that Rajika Kirpalani had started, and I believed that because writing was what I wanted to do, the ideal career would have been journalism.

This crystallised in my mind enough for me to leap at a book called Professional Journalism by Patanjali Sethi in my school library. I borrowed it for my cousin, who was much older, and who wanted to be a journalist, and before I knew what had happened, she told me she had joined Bombay College of Journalism and that Patanjali Sethi was her professor there!

That’s how I ended up doing a post-graduate Diploma in Journalism there as well, though I was still in my first year of B.A. Dr. Pragnya Ram, who ran the programme with Dr G. Balani, recently told me that they had never before, and never again, made an exception like this for anyone.

I was 17, attending undergraduate Arts classes during the day, and post-graduate Journalism lectures in the evening. No one knew how young I was until I was sent to The Times of India for a six-week internship and the News Editor, who was also one of my journalism professors, offered me a job at TOI. I was forced to tell him then that I could not take the offer because it would lead to Union problems since I still did not have a degree. He told me that when I graduated, which he assumed would be very soon, I could walk into the Times and was astounded to learn it would be another three years! By the time I did get my degree he had taken on a post-retirement position with Mid-Day, which I discovered when I walked in because someone else had recommended my name for a job there.

Through my college years I had continued writing for newspapers, including ‘middles’ for The Times of India. A.S. Abraham, who handled that column, told me nine out of ten middles ended up in the bin, and if mine was going to be published I would see it on the page in about three weeks. As it happened, I did!

I wrote the Leisure column for Business India, which involved speaking to three or four executives every week. Once, I asked my English professor if I could leave the class early since I had to meet one of these gentlemen. Otherwise, I told him, I would have to miss the class entirely. My professor was taken aback but ended up announcing that since I needed to meet someone, he was letting everyone off early! I think it was the one time that I was truly popular among my classmates…

In my final graduation year, I received a first class in English Literature (though just about). Apparently, this was an achievement unheard of in those days, as an M.A. the lecturer who recognised my name told me later when I met him for the first time. Thanks to this, my Principal at Jai Hind College offered me a job as a lecturer, saying that he was willing to waive the required teaching qualifications. This was thrilling to me as a young graduate, but I found myself turning it down, since I was already well entrenched in my Journalism career, and still writing poetry quite prolifically.

I’ve done some interesting things as a journalist, including climbing up a rope ladder (me, with my fear of heights!) to spend a night on a rooftop at Deorala, where a young girl called Roop Kanwar had committed – or, more likely, was made to commit – sati in the 1980s. The Chunri Mahotsav was scheduled for the next morning, and the crowds gathering had led to a stampede-like situation, so the rooftop was the only safe space.

I’ve also interviewed Jayalalithaa, the politician, after ten days of badgering her for an interview, even as local journalists laughed at me for even trying since she refused to meet them. I was travelling to Chennai (then Madras) because the filmmaker Shyam Benegal’s wife had told us about a man who was hiring out wild animals for films, including a tigress whose mouth he would stitch up every time.

As I was leaving, my editor, Behram Contractor (the legendary Busybee), said: “If you are going to Madras, why don’t you interview those two women?” I knew he meant Jayalalithaa and Janaki (M. G. Ramachandran’s wife) but it was Jayalalithaa who interested me more.

The night before I was to finally interview her, I was speaking to the photographer at around 10 p.m., when I suddenly keeled over in pain. “I’m 26 and dying of a heart attack in a hotel room in Madras”, were the first words that came to mind. I ended up in a hospital for observation overnight, with the doctor telling me I should take the first flight home; it was pleurisy, he said, and could be fatal. Of course, I ignored this advice and stayed to do the interview. I later discovered that his diagnosis was wrong; it was something else that needed attention but would not kill me.

I also managed to track down the animal guy somewhere near Salem; he even invited me to dinner, thrilled by the thought of being written about in an English newspaper.

I also once looked for, and found, a lady who said she was the Rani of Jhansi reborn. The only information I had was my editor’s statement, “There’s a woman in Wai who is saying she is the Rani of Jhansi”. In the end, after travelling to Wai, Satara and then Sangli, asking random people if they had heard of such a woman, I found her. During our interview, she mentioned a professor of parapsychology in Poona who had studied her case. She could not recall his name but mentioned that Tarun Bharat had done a story. So, I went to Poona and managed to locate him; he said there were aspects to her story that could not be entirely dismissed.

For many years, in the busy feminist era of the 1980s, I also wrote about dowry deaths, and women being raped and murdered; the feminist groups in the city began to believe that I was an activist, not just a journalist reporting on these issues, and once when I went to cover a women’s morcha, I found a placard being thrust into my hands, and ended up marching down the streets with it!

I’ve also traversed the underbelly of Mumbai at night, meeting drug addicts and visiting the homes of peddlers, and gangsters such as Haji Mastan. For a little over a year, I also worked in Hong Kong, with the South China Morning Post.

If anything, my career in journalism certainly stoked my adventurous side!

All this must have influenced my poetry in subtle ways, but it took me many years to recognise that journalism and poetry were fundamentally different entities – while one required going outwards, the other completely involved an inward journey. I have often wondered – if I had accepted my principal’s offer and indeed joined the academic world, would it have been a better thing to do? I suspect I would have done it well, and enjoyed some aspects of it, but I’ve also realised everything has its exciting and dreary moments, and I’m sure being a teacher has its share of both!

At this stage of my life, I’m beginning to make peace with my choices. Every step leads you to the next, and there have been many good things in my life that happened because of the situations I chose in my early days. I do not write as prolifically as I used to, but poetry has still been a constant companion.

Urna: We would like to know about your writing schedule and process. Who are some of your favourite novelists and fiction writers? What are your tips for young poets?

Menka: Unfortunately, I have never had a particular writing schedule or process and am full of admiration for people who maintain such discipline. When I was younger, I wrote anywhere, and everywhere – in a busy magazine office (Diary of a Mad Housewife, when I was still single); on the backs of bus tickets because I had no other writing paper, and sometimes even on the palm of my hand. Why Rabbits Never Sleep was literally a nightmare poem, written at 3 a.m. Now, I find the note-taking app on my phone a useful tool.

Today, I write much less, though it occurs to me that one need not always wait for words. My poem, Iron Woman, which has two versions, one of them shorter, seems to repeatedly get quoted when people speak about my work; it has also been translated into Russian and a few Indian languages. I wrote it during a dry phase, when I decided to read up about shooting stars and discovered that meteoroids are lumps of iron. Inspiration can come from anywhere, I realised; you just have to let facts speak in your quietest moments to the deepest parts of yourself.

Another time, several years ago, I thought I was done, and would not write another poem again. So, I wrote some words that had the potential to go in many directions: “One day, he said…” In 15 minutes, I had a poem that I felt could find a place in my next book. This is the poem Interlude.

My favourite novelists and fiction writers? Different ones at different stages of my life; Ismat Chughtai was always top of the list. Among contemporary Indian writers, C. S. Lakshmi (Ambai) is someone whose work I wish I could read in the original; what I have read in English translation is so nuanced and insightful. Shikhandin is a writer who deserves far more attention than she receives, and Rochelle Potkar’s Bombay Hangovers has some wonderful stories. Kavery Nambisan is also an excellent writer, and I’ve enjoyed reading Anita Nair. I recently read Saikat Majumdar’s The Middle Finger, whose protagonist is a poet who had “taken the leap to follow the life of her poems. They came from anger and hissed like droplets on hot metal.” She also says: “I write poems. I don’t own them. They leave me once they’re out there.” This is something that I have always personally felt about my own work.

Mainly, however, I prefer to read poetry, and am currently devouring K. Satchidanandan’s The Whispering Tree, translated from Malayalam by the poet. I’ve always been a great admirer of his work. I have a poetry project in mind with Sindhi folk tales and am trying to read up as much as I can about them.

As for my tips on writing poetry, there are a few things that work for me, and I have written about them elsewhere, ( https://www.thehindu.com/features/metroplus/nxg/the-value-of-silence/article5474410.ece ).

Mainly, however, I would stress the importance of cutting out the noise and listening to what the core of your being is trying to say. Through all the clutter and the din, you need to always be true to yourself.

***

Caption: Urna reads a poem by Menka Shivdasani

***

Five Poems by Menka Shivdasani

#1: FRAZIL

Like an ice crystal formed in turbulent water, you hang suspended, in your glacial zone, letting currents swirl around you in the roughened sea. In the coldness of this spinning space, you feel safe; you know nothing of the world outside, have never heard of global warming or drifting ice. Sometimes the warm glow of Northern Lights bathes the frozen shell that lies above. Then it goes black, but you are used to that too. Crystal in this liquid shimmer, keep shining. Make believe the world is far away; make believe you still have time in these quiet depths. Tomorrow will come but for now, winter is your friend.

#2: BASS NOTES

“How come your hair is so silky?” the black musician asked, and she, half-asleep, said Hong Kong was full of gloss and sometimes the place got into your hair. He was a professional, and they were playing games with each other, fine-tuned notes on silken skin. “The trouble,” he said, “is you’re too sensitive,” and drew music from the guitar strings on her head. It was when he got to the bass that something changed. Later, he asked, anxious: “Did you, baby, did you?”, for at a crucial moment, there were silences he didn’t expect. “I always come quietly,” she told him, not adding: “I always go quietly too.”

#3: RETURNING TO EMPTINESS

Far beyond where bulldozers break the mountains, four hundred steps up a bare hillside, is a shivalingam that bleeds on touch. The world gushes past in a broken pipe; some of us fill water from the cracks, some of us sit, fat stones, on rough-shod slopes. Some of us are suspended in the sky. This is a return to emptiness, there salt pans breathe tales of long-past liberties. Men smoke their pipe dreams silently; women wear rouge like blood in war. Trains spurt into stations like lost love. Out in the distance I bleed on touch. But why does the stone stay dry?

#4: SARCOPHAGUS

The skeleton, grinning, cried for flesh and skin. No sound wave would condescend to move, so no one heard except the coffin walls. Once there was more than bone, but they dumped him in the cemetery, till slowly, the flesh turned fungal, fed the worms. Yes, they’d chanted songs on the occasion, but some time one’s term expires, and death must go on. The sound waves finally transmitted the message: by the time they came, the skeleton had turned to ash.

#5: THE WOMAN WHO SPEAKS TO MILK POTS

Boil. I shall ignore that steely glint and watch you. I am simmering too, padding about with cottonball claws, arching my back before the flickering flame, scratching behind my ear. You’ve got the cream, melded into every drop. I will bide my time till you separate, and strain you through wire mesh. I’m on edge now, about to overflow. Don’t sit so self-contained, snow-white and cold. I shall turn the heat up, put the lid on. Watch me.

Photos sourced from Menka Shivdasani

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By