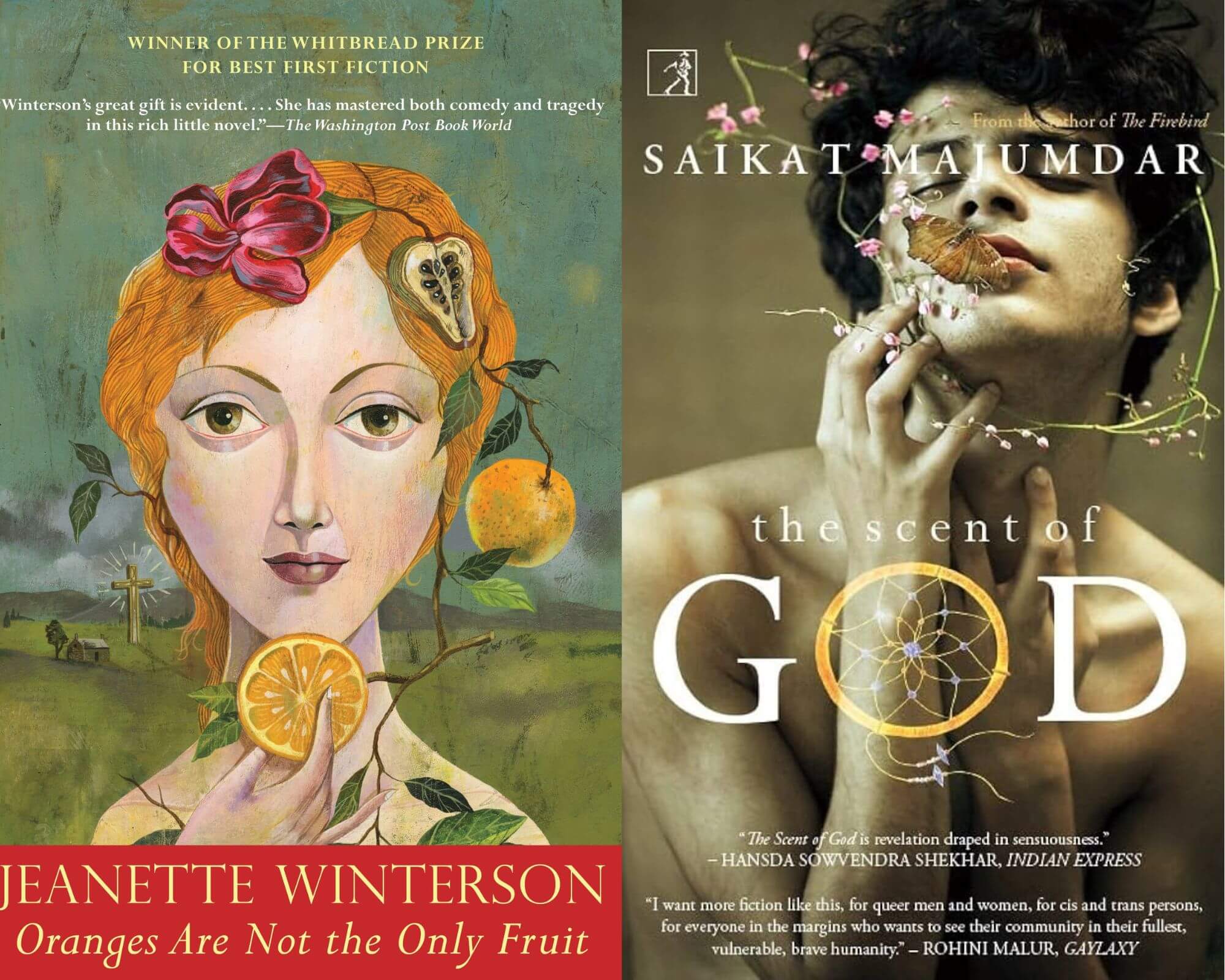

Ketaki’s erudite article explores same-sex love using Attachment Theory, comparing Majumdar’s “The Scent of God” and Winterson’s “Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit”, exclusively for Different Truths.

Abstract:

This article is keen on judging same-sex love as a viaduct to a higher level of attachment. According to the Attachment theory, the romantic partners also share an emotional bond, which decides the tenability of their relationship. Saikat Majumdar’s the Scent of God is pitted against Jeanette Winterson’s Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit to prove that physical love between the same-sex-lovers may or may not upgrade to the level of a strong and inextricable attachment. However, Majumdar’s protagonists are true to each other sharing an unalloyed bond of love and mutual dependence. On the contrary, Winterson’s lovers stay only on the superficial level, they even renege on promises and fall apart because of the intimidations of the Pastor, a parent or both. Thus, for them, the depth of love, of whichever orientation it may be, falls far short of the requirements of a tenable attachment that brooks no separation. If love cannot uplift lovers to an everlasting attachment, ‘love’ itself would be a misnomer. The detailed analyses of the two novels have been carried forth, meticulously, keeping the Attachment Theory of psychology in view.

Saikat Majumdar’s the Scent of God is a tale of the same-sex love of two boys in a boarding school run by a monastic order of colossal repute. This is not just a run-of-the-mill narration of two boys attracted towards each other physically but also daring to transcend all set boundaries. In this essay, the writer intends to delve deep into the interpersonal attachment of the protagonists and compare this novel with Jeanette Winterson’s Oranges are not the Only Fruit, from certain perspectives. And of course, Majumdar’s novel is a realistic portrayal of two adolescents studying in a school run by a monastic order, whose sexual orientation leading to an unbreakable attachment has been put on the anvil for analysis. Majumdar has been seriously criticised for writing against the students of such a reputed institute, though his intention is innocuous and different. E.G. Hepper and K.B. Carnelly (2012) in their well-acclaimed essay, “Attachment and Romantic Relationships” opine, “Although research into attachment processes began with infancy, Bowlby viewed attachment as relevant from the cradle to the grave. He argued that adult love relationships function as reciprocal attachment bonds, in which each partner serves as an attachment figure for the other.” [Hepper & Connelly: 3]

In Majumdar’s novel, Anirvan [Yogi], a boy from a boarding school, run by monks of a religious order, used to watch a cricket match on the television. In contrast, his friend Kajol, a soft-spoken, taciturn boy had to yield to the caress of Anirvan. He never took away his hands lying in Anirvan’s while the excitement triggered a kind of yearning in Anirvan, who took Kajol’s hand in his. When in the evening, while the boys were yet to return from the football ground, Anirvan and Kajol stood beneath the shower stall to try the mystery of getting to know their intimate organs and limbs. Kajol drooled over each move of Anirvan’s fingers, silently, with tacit consent. A secret bonhomie kept cocooning the two, which Kamal Swami, the thirtyish monk could hardly make out. He showered his affection on both the boys, quite unconditionally.

But much later in the book, Anirvan’s love for Kajol took a serious turn, which did not seem as puerile as before. Their physical intimacy at late afternoon after the football game every day spoke volumes of their growing attachment to each other and their final outburst of union in the monk’s room was even more corroborative of their homosexual bond, an attachment, which assured each other of a safe, loving proximity:

“They were safe. It was monk’s room.

They didn’t know how their bodies got entangled.”

Two Coming-of-age Novels

the Scent of God by Saikat Majumdar, like Jeanette Winterson’s Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit is a coming-of-age novel, no doubt. But the religiosity practised in Oranges…can in no way be the exact parallel for the scent…But in both the novels, the austere practice and the list of dos and don’ts among the growing children have adversely affected the attraction between a boy and another boy or a girl and another girl so obviously. Both Anirvan and Kajol and again Jeanette and Melanie suffered the interpretation of their attraction in a more or less similar fashion by the austere religious system they were cocooned in. If Kamal Swami could sense such an affinity between Anirvan and Kajol, he might not spare them his lashing. On the other hand, Jeanette had been admonished by the Pastor and her mother, fearing she was possessed by a demon. Their attachment quotient lay in their love for each other giving way to inordinate passion, which helped them stay in certain reassurance of emotional security.

In Winterson’s novel, Jeanette’s mother was a truly religious soul, who kept her daughter busy by checking her knowledge of the Bible. Whether she liked it or not, she had to come up with the answer. Her mother loved to see her as a god-fearing, pious soul. But Jeanette loved to listen to Elsie’s stories from classics, as they were far more interesting and enlivening in nature. After the surgery, when Elsie read out to her from different literature books, her heart felt soothed, and her mind seemed to be regaled with a fresh breather. Jeanette did not falter to go physical with Melanie, who filled up the vacant nooks of her mind. Pastor Spratt and her religious mother kept admonishing her severely. A little twist in the usual mode of sexual union, and her mother labelled it as ‘unnatural passion.’ Why unnatural? Was it because it questioned the established norms of sexual behaviour and went along ‘queer’ lines? In fact, since the day, Jeanette talked about her mental proximity to a couple of spinsters who ran a paper shop and offered sweets to her, her mother began to dissuade her by denigrating them as; ‘dealing in unnatural passions’. It was beyond her comprehension as she could find nothing wrong in it. She even wondered why her mother was dead against putting her in a school, labelling it as a ‘breeding ground’ .But breeding ground of what? Of evil? Of something unsavoury? Jeanette doubted her mother’s words but she was not at all happy at school, neither with her classmates nor with her so-called friends. Back home, she stays cooped up in the kitchenette with her mother, who remained preoccupied with various radio programmes related to the Pentecostal Church, because of helping the lost and the downtrodden. In her school, as she narrated experiences with her devout mother, she was mocked at, bullied. Hence, in the school, she was cornered and felt like a fish out of water. No attachment grew with her classmates let alone the teachers. Thus, it gave way to a disturbing sense of insecurity in the school.

Even her teachers like Mrs Vole did not leave any chance to humiliate her, if she came across one. She did not falter to confuse Jeanette with an innuendo, as she ran into her in the class, “You do seem rather preoccupied, shall we say, with God.”

Various Bonds of Attachment

Various bonds of attachment are being derided: her non-attachment with her classmates, and her mother’s over-attachment with the Lord, as a missionary. Emotional security is a chief aim in this regard.

Or, again some other day, she charged her almost for no veritable reason, “…this is perhaps more serious, do you terrorize, yes, terrorize the other children?” Though she protested immediately, Mrs. Vole had much stronger point to malign her, “ You have been talking about Hell to young minds.”[Winterson, 54-55]

Majumdar’s Anirvan and Kajol struck a friendship with each other in a residential school run by the monks of a certain order. The exterior realities seemed to dissolve around them as they walked together, though they belonged to the boarding school. In the evening, both of them used to peep into Kamal Swami’s room, who remained engrossed in meditation and the two adolescents sat watching him keenly, perhaps being inspired by his asceticism but the meditative trance of Kamal Swami opened up opportunities of proximity, physical propinquity for the desire-wracked adolescents:

“The Swami sat in a narrow space between his bed and the wall. Kajol went and sat behind him on the floor. Anirvan sat at the end, behind Kajol.

The Swami closed his eyes and went back into meditation.

…The windows were shut. The smell of incense danced like a raincloud and the air felt cool. Anirvan reached out and encircled Kajol’s waist with his arms.” [Majumdar: 49-50]

‘Unnatural Passion’

Jeanette had fallen for Melanie and both of them were adolescents like the boys in Majumdar’s novel. But once it came out into the open, the Pastor began calling Jeanette and Melanie to have fallen into the clutch of demons and Jeanette’s mother labelled this as an ‘unnatural passion’. Neither same-sex love is unnatural or demonic, only manifestation as this is a kind of sexual orientation, which can neither be judged as ‘good’, ‘bad’, ‘agreeable’ or ‘pernicious’. Just a way of expressing oneself sexually, that’s it. People may not accept it but must in no way demean it. Orientations may vary from individual to individual. Ruth Vanita in her 2005 book “Love Rites” validates same-sex love and even supports same-sex marriage. While talking about same-sex love in the Indian context, Ashwini Sukthankar in her “Facing the Mirror” gives a piece of her mind and calls this same-sex love an ‘unnatural passion’ like Jeanette’s mother,

“Our status as myth means that many people truly believe we don’t exist and it means inhabiting the domain of their ignorance, which is neither acceptance nor condemnation.”

[Sukthankar: Introduction: xiii]

In both these coming-of-age novels, both Majumdar and Winterson write that in adolescence, sexual orientation can find its early manifestation and for that, they are brought to the book by their near ones or their elders. But such orientation can also strengthen the attachment between two souls, which may be everlasting like Anirvan and Kajol and even can fizzle out as in the case of Jeanette. In the case of Anirvan, his blind attachment to Kajol could hardly be disclosed to anyone. Each day in the hostel they remained in a state of euphoria to enjoy the touch of each other’s body under the shower stall, in the darkness of the monk’s room or whatever. As though, this togetherness would open a floodgate of knowledge and power and joy, heretofore unknown to the adolescents. A long-lasting attachment may demand knowledge and power to fortify such a relationship. The union of two souls hardly entails the opposition of the world around them. Foucault observes,

“Sexuality must not be thought of as a kind of natural given which power tries to hold in check, or as an obscure domain which knowledge tries gradually to uncover . It is the name that can be given to a historical construct: not a furtive reality that is difficult to grasp, but a great surface network in which the stimulation of bodies, the intensification of pleasures, the incitement to discourse, the formation of special knowledges, the strengthening of controls and resistances, are linked to one another, in accordance with a few major strategies of knowledge and power.” [ Foucault:105-6]

Moments of Savouring Life

But as time got wings, Anirvan came under the folds of Sushant Kane, the English teacher, who stayed outside the ashram, and he got the moments of savouring life to a great extent. He slurped the beef juice in a bistro run by the Muslims in a far-off ghetto, and again went out to deliver a rabble-rousing speech with his gift of the gab. But in all these worldly engagements, he was never away from his attachment to Kajol. Majumdar in a few sentences labels this bonhomie as a meaningful one in the given context:

“Kajol’s moist eyes were a lie. Anirvan realized that Kajol knew what he wanted. Anirvan belonged to him. Kajol did not speak much but his will was sharp. He would draw Anirvan closer, tie him up, shape his days.” [ Majumdar:41]

How can this attachment be an unnatural one, when till the last, even after an interregnum of distance between the two cannot extirpate the seeds of longing and desire? If this would have been an ‘unnatural’ one, their bond would have been tenuous or even could have terminated. For example, in Winterson’s novel, Jeanette and Melanie struck a bond of attachment which had been denigrated by Jeanette’s mother and the Pastor of the Pentecostal church, and Melanie had to go far from Jeanette and the attachment grew tenuous and later on, dissolved in the long run. Jeanette built a relationship with a new friend, Katy, but that fizzled out in a short span. Even then, we are reluctant to call any of the bonds to be begotten of ‘unnatural passion’ as for a certain length of time, the relationship held much significance, howsoever, evanescent that might have proved much later, down the line.

But in case the attachments between the friends [or partners] do not last, can we call it an end of friendship begotten of ‘unnatural passions’? Or just a fortuitous end of relationship just like any of the ilk? In Majumdar’s novel, Anirvan [Yogi]’s relationship with Kajol has seen vicissitudes of many kinds like his propinquity to Sushant Kane, his harangues delivered outside the precincts of the ashram, his acquaintance with the exterior world much more than Kajol. Naturally, a hiatus grew agape in between them. Kajol, on the other hand, pursued his studies minutely with all perseverance and sincerity. Again, Anirvan [Yogi] while getting the taste of the outer world, was feeling worldly-wise. During vacations, as he was going to stay at Kane’s, he got the chance to see the best of both the worlds—the spiritual as well as the materialistic. He needed a cover to indulge in the touch-hankering business in the ashram, with a spiritual ambience, though he could mingle with the run-of-the- mill populace, while staying at Kane’s. Through Sushant Kane he came to know Raghav, who used to run an office, which was a ‘co-op where men walked in to buy women.’ [Majumdar: 174]

Rabble-rousing Speech

At Raghav’s office, strange womenfolk thronged in numbers with different sets of demeanours and attitudes. Since proving his oratorial skills at Gol Park, Anirvan was being much sought after by Sushant Kane and his allies on various occasions. He could easily win the populace with his rabble-rousing speech and gradually his demand in their circle shot up. Anirvan was not very happy as he was pining for the togetherness with Kajol, with whom the hiatus grew threateningly. That day, Anirvan [Yogi] was caught off guard by the woman who enticed him to a union, which Anirvan was far from enjoying. Rather, he began to miss out on the presence of Kajol, who stood between this ‘unnatural passion’ aroused in him and the much-craved-for attachment he had with Kajol.

Majumdar’s fecund pen ran,

“He felt her heartbeat of happiness as she crushed him to her chest. Choking on cream-soaked cashews Yogi’s lips mashed themselves against her sharp collarbone. They were real; they reeked of adulthood. Kajol’s bony body passed through his senses….

…Spent all of a sudden, he’d marvelled at his hatred for her, a hatred more like awe.

Like Kajol’s body, its memory was half-formed. It tugged at his heart and made it wet.” [Majumdar: 183-4]

Double-edged Affinity to Both Sexes

Thus, Anirvan’s double-edged affinity to both sexes brought the question of attachment to the fore. One attachment was a fragile one, with no commitment or pleasure while the other one was just to the contrary. But the latter proved ephemeral, with no prospects at all. Again, same-sex love sought fulfilment in the moment’s pleasure leading on to a certain commitment while heterosexual love for a person with unipolar orientation proved futile, just nonsense. However, Foucault had been there to question all sorts of attachments alluring a homosexual, though coming down to settle on an ultimate logical finding:

“This new persecution of the peripheral sexualities entailed an incorporation of perversions and a new specification of individuals… The nineteenth-century homosexual became a personage, a past, a case history, and a childhood, in addition to being a type of life, a life form, and a morphology, with an indiscreet anatomy and possibly a mysterious physiology. Nothing that went into his total composition was unaffected by his sexuality….

Homosexuality appeared as one of the forms of sexuality when it was transposed from the practice of sodomy onto a kind of interior androgyny, a hermaphroditism of the soul. The sodomite had been a temporary aberration; the homosexual was now a species.” [Foucault: 43]

Altering Orientation

Hence, Anirvan could not dream of altering his orientation, though his preferences might change. He might not bolster the advances of the prostitute at Raghav’s office, but his soulmate, Kajol, was never forgotten, even when they were physically distanced, more accurately, mentally poles apart.

In Jeanette Winterson’s Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, no such commitment however was found in between Jeanette and Melanie. About this attachment, we have talked at length earlier. But here the ‘unnatural passion’ or perversity took a backseat as according to Winterson, “…no emotion is the final one” [Winterson:64] Thus Jeanette and Melanie were attached by a bond of a strange love, which drew them closer fast and made them feel each other with much passion and empathy.

Of course, despite several similarities, some basic differences are there between Majumdar’s the Scent of God and Winterson’s Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit. The primary difference is, of course, the gender. Majumdar’s homosexual duo prove in the long run that they cannot stay without each other and all other relationships are just superficial compared to this one, while Winterson’s lesbian couple keep changing their preferences, thus proving that a lesbian bond for the adolescent Jeanette was tenuous, her attachment to Melanie, Elsie Norris or Katy was homosexual, but none of these bonds would survive the onslaughts of time. They came and faded away at the slightest threat or opposition from the Pastor or her mother or even for her change of definition of attachment. It may be so, that, Anirvan and Kajol were connected even beyond physicality, while Jeanette’s hankering for sexual gratification remained confined to physical union only. The role of mind was perhaps minimal in Winterson’s lesbian pair.

When Anirvan met Kajol and came to know about an ace-debater of Class XI, Aditya Som, he was taken aback by Kajol’s words, which carried a sanction of his mental terrain, his strong attachment with him, he felt:

“He’s alright. But nothing like you,” Kajol said, his eyes looking into Yogi’s. [ Majumdar: 206]

While he was left alone with Kajol as Prashant Kane walked off, Kajol broke into emotional babble,

‘I can’t spend my days without you.’ Kajol’s voice trembled.

‘Why did you leave?’ He whispered.

His eyes were wet. [Majumdar: 207]

Normalising Situation

Though Anirvan tried to make the situation normal, Kajol did not hold himself from being candid and true. Majumdar writes,

‘I loved those days,’ Kajol whispered.

‘Kajol, we were kids’. His heartbeat wildly as he said it, ‘It is the past.’

‘Is it?’ Kajol asked. ‘The past? How easily you say that.’

Words flooded through Yogi, but he didn’t speak.

He was terrified that his voice would sound hoarse, that he wouldn’t be able to call it his own. [Majumdar: 208]

Winterson at the end of each section narrates a story which has a subtle reference to the main plot. At the end of the section, Exodus, Emperor Tetrahedron was visited by a theatre which could be enjoyed equally as he had many faces and while watching the exhibition of comedy and tragedy from different angles, he came to the conclusion that “no emotion is the final one.” [Winterson:64]

This is just a preamble to the emotional attachments Jeanette was about to have with Melanie, Katy et al. And the emotion hardly mattered to her as it ran to the brink of dying out, fading. Even yielding to physical love with same-sex appeared to be a taboo, begotten of a temptation that led one to stand accursed and eternally damned in the long run.

How could Jeanette turn her deaf ears to the famous quote from Redemption Hymnal? The first verse of ‘Ask the Saviour to Help You’ ran as follows:‘

Yield not to Temptation, for yielding is sin,

Each Victory will help you some other to win.

Fight manfully onwards, Dark Passions subdue,

Look ever to Jesus, He will carry you through.’ [Winterson: 67-8]

Yet, the call for same-sex love could hardly be turned down. She was won over by the immaculate love of Melanie, which she banked on much to tide over the ostracism in school, and the loneliness back at home. But just as her mother and Pastor Finch thrashed their blooming relationship in the harshest of words, Jeanette did not nurse the thought of backing out, rather Melanie wanted to leap up to the safer end. She became quiet and withdrawn, planning to put an end to this budding love.

It all started when she had told her mother about her staying at Melanie’s place almost every night, and again when she had told Melanie that she loved her as much as she loved Lord. And the whole thing reached its peak when the Pastor in the Church thundered, pointing to Jeanette and Melanie,

“These children of God have fallen foul of their lusts…These children are full of demons.”[Winterson: 116[ Jeanette mustered courage to protest though Melanie gave in to the inane diktat of the Pastor, “ Do you promise to give up this sin and beg the Lord to forgive you?”[Winterson:116] Her answer in the affirmative left Jeanette numb and dumbfounded. She, herself, had boldly protested when crossed about her love for Melanie, “

…I mean of course I love her…. To the pure all things are pure.” [Winterson:116]

Things came to such a sorry pass that when Jeanette went to Melanie’s place to talk to her, she turned a nonchalant face to her and later she told on Jeanette’s face that,

“…I repented and they told me I should try and go away for a week. We can’t see each other, it’s wrong.” [Winterson:124]

Even that day, Jeanette did not hesitate to make love to her and kiss her repeatedly. But Melanie did not think twice to put an end to such a ‘demonic’ relationship as stamped by the Pastor of the Church.

However, Jeanette started a new relationship with a new convert, Katy, who seemed to respond to her call. But by this time, Jeanette was coming of age. She grew up to understand life, her cravings and even who would accept her offer with an open mind or not. She even became mature enough to make decisions regarding her existence, with a partner or without one or with her mother, for whom Pentecostal Church activities were meant to be the ultimate.

Involvement with Other Partners

Jeanette approached Katy differently and Katy wanted to know the truth about her involvement with other partners. Jeanette made a clean breast of it saying that her affair with Melanie

‘had never really ended.’[ Winterson: 142] Though Melanie had written to her for months, she could not see Melanie in person. So she begged Katy of her help emotionally. Her mother would not help her as she came to know of her latest involvement with Katy. This conversation would make the things clear to the readers:

‘You will have to leave,’ she said. ‘I’m not havin’ demons here’.

‘Where could I go? Not to Elsie’s, she was too sick, and no one in the church would really take the risk. If I went to Katy’s there would be problems for her, and all my relatives, like most relatives, were revolting.’

‘I don’t have anywhere to go,’ I argued, following her into the kitchen.

‘The Devil looks after his own,’ she threw back, pushing me out. [Winterson: 148-9]

Stay Alone

But she had to move out to stay alone. She did that. Thus, in her case, she could not build any strong attachment with her partners. She was dumped by her mother; she had to take up odd jobs to keep her body and soul together. Her mother hurt her saying, “She’s no daughter of mine” [Winterson:169] However, at the tragic failure of Morecambe Guest House and the Society for the Lost her mother felt distracted and Jeanette came to visit her, helping her with the headphones so that she could carry on with her Radio Broadcasts, thus strengthening the mother-daughter bond.

On the contrary, though Anirvan and Kajol were coming of age in a residential school run by a monastic order, their bond begotten of so-called ‘unnatural passions’ grew into a sustainable attachment. Even Kamal Swami unlike Pastor Finch or Jeanette’s mother gave them a refuge, even a shelter to be initiated into a higher level of attachment.

As Anirvan moved out to stay with Sushant Kane, Kajol might have sequestered himself from him, mentally, as Melanie did from Jeanette. But he began to miss Anirvan instead. The world seemed to be meaningless without Anirvan. And later, when he got to see Anirvan, he could not resist the temptation of being in his arms in all happiness. Anirvan and Kajol had gone to the monk, Kamal Swami’s room, where their same-sex love grew into a firmer attachment, which began to bloom into a meaningful one. Kamal Swami could have doubted them, their propinquity, but somehow they were intelligent enough to keep their relationship under a cover. But even if it came out into the open, would it have fizzled out as in the case of Jeanette and Melanie or even Katy for a short term? Would they be stamped as children under the influence of demons? That cannot, however, be presumed or surmised. But neither Kamal Swami nor Sushant Kane nor his brothers had ever suspected any sort of ‘unnatural passions’ in the two quiet, talented boys of their residential school.

Should we then be given to understand that Jeanette and Melanie or Katy were not extra-cautious about keeping their relationship a secret, and hence, it could grow into an inseparable attachment? Or was it because of Jeanette’s off-the-guard demeanours, that her relationship with Melanie could not sustain to see better times of elevation to a meaningful attachment? Even though, for the sake of argument, we go for the intelligence of Anirvan and Kajol, the fact of their true love which goes beyond physicality can hardly be gainsaid.

Serious Corollary

The conclusion of both novels calls for a serious corollary into play. Love for bodily attributes may not last long but love beyond the physicality might get elevated to an attachment in which physical love plays just a small part. Jeanette’s early initiation into the missionary might have left her quite destitute within, of course, emotionally. Hence, same-sex love was a viaduct to fight off moral turpitude, the inner loneliness, consequently. The Church would not accept her proximity to a boy even. Graham, the newly converted, was a butt of ridicule, being suspected as a plausible crush of Jeanette. As it was proved to be wrong, the Church heaved a sigh of relief. But the same Church charged Jeanette and her love, Melanie, so meanly that they had to repent and Melanie shrugged off the tenuous relationship and disowned Jeanette, who was shocked by her life by such ruthlessness or cowardice of Melanie.

If we veer our attention to the concluding lines of the Scent of God, a barrage of critical enquiries might get a befitting answer:

“At the end of seven days, they would return to their patron—Kamal Swami.He would give them the white robes. They would be brahmacharis. Men who walked the god-path….

The Lotus started to hum the prayer. It was the song they sang every evening in the hostel. In the monk’s lone voice, it sounded desolate.

Kajol and Yogi sat close to each other, their naked hands entwined. They had found peace.

Kamal Swami stopped. ‘Twelve years,’ he said. ‘ It will take you twelve years to earn saffron. The Hue of Renunciation.’

‘But I know you boys will earn it,’ he smiled. ‘I trust you.’…

Kajol wrapped his arm around Yogi. A soft bony arm. He felt Kajol’s nails scrape his flesh.

Yogi entered his hug and felt safe. His corpse melted into nirvana. [Majumdar: 233-4]

So, Anirvan and Kajol’s same-sex love gets elevated to a higher plane where their mundane desire seems to be burnt into a higher attachment. Thus, crude physical attraction crumbles down, leading on to a new attachment, a precious, pure and everlasting one.

Winterson’s Jeanette tries to find togetherness in same-sex love and even assurance of a stable relationship. But neither with Elsie nor Katy, Jeanette finds love, to make herself feel cocooned and secure. Melanie seemed to walk out on her forever. The spiritual ambience that gripped her mother or others of the parish for that matter could not appear to be so elevating or liberating as we find in the case of Majumdar’s adolescents, growing mature, under the tutelage of Kamal Swami. Jeanette had to fend for herself on her own, though her mother proved a bit compassionate in the end. She became a part of the missionary too, but to no avail. Her loneliness is sadly juxtaposed against the ‘bonhomie’ Anirvan and Kajol seemed to be blessed with. Thus, Majumdar’s novel has a salubrious finale while the hint of ‘Kindly Light’ in Winterson’s novel is a semblance of solace, ringing down the curtain rather abruptly on Jeanette’s existential loneliness!

Works Cited

Majumdar, Saikat. the Scent of God. Simon Schuster, New Delhi, India, 2019.

Winterson, Jeanette. Oranges are Not the Only Fruit, Vintage, U.K. 1990.

Sukthankar, Ashwini. Facing the Mirror: Lesbian Writing from India.Penguin Books,New Delhi, India, 1999.

Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality: An Introduction, Volume 1, Vintage Books, New York, 1990.

Hepper, E.G. & Carnelly, K.B. “Attachment and Romantic Relationships:The role of the models of the Self and the Other” in Paludi, M. ( ed.)The psychology of Love ,Vol 1, pp 133-154, Santa Barbara CA: Praeger, USA, 2012.

Photos sourced by the author

By

By

By

By

Thought Provoking!!