Reading Time: 15 minutes

Chapter 1

The rain had picked up again after a next to nil lull! So had the wind whooshing wildly through the tall ashokas and palms of Shashank’s house. His young daughter Shweta, sitting in the veranda with the radio in her lap, had to hurriedly wheel her chair in to protect herself from the big droplets pattering down thick and fast.

It had been pouring, virtually nonstop, the whole of last week. Nothing had changed; glowering clouds, flashes of lightning, thunderous downpours – without respite. It seemed as if the heavens had opened up, ready to empty all their pent-up fury on earth. Roads, flooded with rain water, had turned into rivers. The diffused headlights of vehicles perforating the shroud of darkness seemed to be crawling along surreptitiously as if not to offend the scourge of Nature. Moments back

, there had been a noisy squall, soon to be replaced by a thick curtain of rain marching down the streets, heavy and remorseless, trumpeting along every lane of the city. The wrath of the rain god had sent all life forms — human as well as animal, scurrying into their shelters; only those with no means of protection were standing hapless – bearing the brunt of Nature’s fury an

d praying for some sanity to return to earth.

The holy city had come to a virtual standstill. Fallen trees, disrupted electricity and communication lines, water logging in low lying areas – all these had thrown normal life out of gear. The district administration had dutifully shut down all schools and colleges sine die. The government offices, though open, registered thin attendance and skeletal staff.

Far away in the mountains, cloudbursts and continuous rains had raised the water level in the catchments of Ganga and Yamuna, causing them to appear swollen, scary and turbulent. The elevated sandy banks on either side of the rivers had been fast diminishing with every passing hour, indicating the bulging underbellies of the rivers rising to dangerous levels. No longer did they flow quietly, passing by the city, attracting devotees to come and wash off their sins. The earthy brown colour of Ganga and the turquoise blue of Yamuna were now donning a single uniform hue of foaming white, a single tone of roaring waves, sweeping off whatever came in their way; entire trees, sheets of hyacinth, logs, boats – in short, any object that could float.

The flotsam rushing past reminded Shashank of someone long lost: Where has he been drifting? Like lost driftwood? Would he not return home? Imprisoned within the four walls of his house, having nothing worthwhile to do, Shashank found it hard to kill the free time he suddenly found at his disposal. He went around from one room to another, inspecting, checking to see if anything anywhere warranted his immediate attention. Soon enough, he found himself inside the store; where he had not stepped in for ages.

There was a dusty haphazard pile right in front of him, consisting of miscellaneous items that had ceased to be of use over the years. A pedestal fan, cricket bats of different sizes, a black and white television set, an old lawn mower, plastic pipes, empty cartons, deflated footballs, a pram, a tricycle — all piled up on top of something that was on top of something else. Shashank smiled vaguely, as a few bubbles of excitement rose to the surface, from his pool of memories. But was he not supposed to banish these memories from his mind? Was he not supposed to keep distance from these swirling waves of pain that he had shut, locked and sunk to the bottom of the pool, so that they lay in a dormant state until they were dead and fossilised? No, Shashank did not want to remember anything.

With lightning speed, he stepped back and was just about to pull the door shut, when he discovered that all this while, he had been standing in a pool of black liquid that was being fed by a pencil thin stream meandering from the shelf on the left. He quickly set about finding the source and climbed up the mound. Hah! So this was it! It was the kadahi containing amla and henna mix that Bina had soaked overnight for conditioning her hair, but had not been able to use the next morning due to her asthma attack. The rain water getting in through the skylight had filled it up and was overflowing and trickling down the shelf. Probably, Chandan, their domestic help had placed it in the safety of the store to ward off Buzo, the Pomeranian pup, from carrying out his misadventures. Last week it had jumped into a bagful of wheat flour in the kitchen and came out white-washed from tip to toe. In this case, with the gooseberry and henna mix, chances were that Buzo would come out dyed jet black. Chandan was becoming wiser with each of Buzo’s mischief, Shashank thought with a smile. He removed the erring kadahi away from the skylight and bolted the store behind him.

*****

There was at last a brief lull. Shashank looked up and scanned the skies. He was delighted that after a long time, blue dominated the isolated patches of grey. His watch showed three minutes past ten. He peered over the balcony and craned his neck to survey the neighbourhood, exploring the possibility of a quick stroll outside. Everything around looked soaking wet. Every perceptible depression was filled to the brim. But Shashank could not care less. He had to venture out of the confines of his home for a while and breathe in some fresh air. Dashing straight into his room, he picked up his wallet from the shelf, thrust it in his pocket and took the umbrella hung on the nail behind the main door. He thought of changing into rubber pumps, decided against it and walked out in his slippers itself.

He must have walked not more than a furlong, when he realised the scale of devastation the incessant rains had brought about. The road was expectedly deserted, with people preferring to stay in the comfort of their homes. Only the neighbourhood boys roamed around aimlessly, whistling and shrieking amongst themselves as they waded through the waters in glee.

‘Hi Boys! Enjoying the rains?’ Shashank waved and called out as he passed them. One of the boys waved back, ‘Yes Sir! We are enjoying our extended Rainy Day!’

‘Enjoy it while it lasts!’ he laughed and moved ahead.

Beyond the market, where the pavements had been eaten up in the last widening, the manifestation of the

A small crowd of customers had gathered at the local dairy. Shashank hurried up and purchased whatever he thought would be needed, if the weather continued to remain intemperate. The stock stacked at the front counter of the dairy disappeared in no time. The van which brought fresh supplies every morning had not shown up since the day before. On top of that, the dairy owner himself was in a hurry to shut down and leave; his own home, in Bagadha area, was under waist-deep water. Shashank quickly picked up a few essentials like bread, butter and eggs and hastened towards home. In the slush outside the dairy, his left slipper got stuck and the strap gave way. He kicked it away like a football, followed by the other a minute later. Then like a soul-liberated or more precisely, sole-liberated man, he walked home, making sure that his feet explored each and every puddle and pool. He felt as happy as a clam, enjoying the moment, carrying no encumbrance of age, profession or even of what others around thought about him. Deep inside, he was connecting with his self at ten years of age, walking back home with a bagful of fallen mangoes, collected from the orchard, in his native village Bindki, after a dust storm.

*****

It was more than an hour since Shashank had been gone. Bina obviously had reasons enough to be anxious. A visit to the local market and back ordinarily took no more than thirty minutes, inclusive of some allowance for quick gossip. Bina could not afford to sit back and twiddle her thumbs! She had to get out for a search. She changed into a sari quickly and went towards the door opening into the rear veranda. She had to bolt it before leaving, as both Shweta and Sonam were still asleep. As she was shutting the door, a faint sound of water flowing out of the backyard tap reached her ears.

‘Will this incorrigible Chandan never mend his ways? He knows the timings of the water supply, then why does he have to leave the tap open? What’s the grand idea?!’ Bina muttered to herself in exasperation. Her bone of contention, however, was not Chandan, but Shashank, whose habit of slipping out of the house without informing anyone, always sent a chill down her spine. Every time it reminded her of someone who slipped away like that, never to return!

Bina took a few steps towards the edge of the veranda to close the tap. Lo and behold, it was Shashank at the tap, hurriedly washing his feet! Like a missile launch having to abort at the last count, she stepped back, banged the door hard and went in.

Two minutes later, she was back in the veranda, armed with a volley of questions. But a bulging bag, languidly resting on the cane chair, changed her volcanic mood. She inspected it and found a few loaves of bread, a pack of butter partially melted within its packing and packets of toned milk, resting above potatoes and onions. She had not expected him to be so thoughtful as far as such mundane day-to-day affairs of the house were concerned. The things he had fetched on his own, without carrying a little chit in his pocket were sure to last a week, in case the weather returned to its previous mood of continuous downpour. Bina was touched!

******

Not far away, just six doors away to be precise, the Johris, Dr Arvind and his wife Yashoda, had been up the whole night. The incessant rains had widened the hairline crack in their bedroom roof, which was caused by a peepul that had taken roots into the plaster, a year and a half ago. When it had first sprung up as a tiny green thing, Moolchand, their gardener, had sought permission to chop it off. But Yashoda had been too superstitious to lend her approval. As a result, it had now become a well-entrenched tree, with branches and leaves spreading out in all directions, giving abode to many a chattering sparrow and bulbul.

Last monsoon, underneath that very corner of the ceiling, there had been an oblong damp spot, where spores of green fungi accumulated; but this year, with the rains pouring down week after week, the soil accumulated in the crevice got washed away, causing a steady stream to trickle down the wall. Yashoda placed a bucket underneath, but to little avail. Gradually, a mini pool began to form there. Initially, Yashoda had managed to cause the thin stream to be absorbed in the empty gunny bags that she had spread out, but when the rains worsened, even piles of rugs and sacks put together were of no help.

Yashoda’s irritation at the damp weather stemmed more from the fact that her arthritic knees made simple chores of mopping and wiping a near impossible task. Arvind on the other hand, had been a valiant trier, trying hard to wield the broom and the mop with the same precision and expertise with which he once wielded his surgical blade, knife and hammer. In fact, a day earlier, he had experimented with a new technique of mopping the floor in standing position, moving the rag under his foot in quick, oval, to and fro motion. But lady luck had no appreciation for his innovation and for all his concerted efforts, rewarded him with a slightly drier floor, and a severely twisted ankle along with a stern reprimand from his wife for attempting tasks that were seemingly outrageous at his age.

As rightly predicted by Yashoda, Arvind was left with a swollen ankle, which he had to nurse the whole afternoon, fomenting it alternately with packs of ice and hot water.

‘When Moolchand is in tomorrow, let him move out all furniture and empty that room,’ Arvind said decisively, but cautiously, avoiding eye contact with his wife. After all, the furniture were gifted as dowry by Yashoda’s father, at the time of their marriage.

Yashoda was quick to retort, ‘Not a bad idea! Let us use the room as a swimming pool then, in which you could swim the whole day. I have heard swimming is a very good exercise and especially during the rains, when people are unable to go out for walks,’ she added. ‘Brilliant! Excellent idea! We can even start a swimming class for kids and charge some money! I don’t think there is an indoor swimming pool in the near vicinity, is there?’ Arvind quipped.

‘Oh, of course we can! The Sheikh Chili that you are, such pie in the sky ideas can come only from you!’ she was acerbic but concealed it with a laugh.

‘Oh, thanks for the compliment, Mrs Sheikh! I can see that some of my extraordinary qualities have rubbed off on you as well. You see, one can’t remain uninfluenced by one’s company for long.’ Arvind’s quick wit and sense of humour always diffused situations like these swiftly and easily.

The stream running down the wall had strengthened by then and the pool was getting bigger and bigger, swelling every moment.

‘Let me see what I can do about this,’ Yashoda said to herself as she limped towards the door.

*****

The horizon was still not a cheerful swathe of blue, but then it was not expected to be either. After all, it was the month of August, which had always been a month when the monsoon was expected to be at its bountiful best. Farmers across the country eagerly awaited this season that showered the parched earth with cool drizzles that gradually turned into heavy downpours. Filling up lakes, ponds and dams and recharging the water tables once again. Only this year, there had been an excess and the repercussions had already been devastating. What next?

Chandan had been tossing and turning in his bed, worrying incessantly. Over the years, he had found it difficult to sleep when it rained heavily, more so if the rains were accompanied by thunder and lightning. During the rains, he would wake up every morning and habitually inspect the ceiling first and then glance around his room to make sure that it was not flooded, that his cot was not floating. And till date he had been lucky; for every morning, he had woken up to intact ceilings and dry floors.

Thanks to the restless night, Chandan had overslept that day. The entire household had woken up already.

‘Run Chandan Kaka run, today you are late,’ teased Shweta, who was sitting in the veranda indulging in her favourite pastime of sky watching. The threatening grey had mercifully beaten a retreat, exposing big and small patches of blues and oranges. Shweta was thrilled at the sight! The sky was her dynamic canvas on which she would let her imagination run wild to derive ethereal pleasure. On a sunny day, she would have easily located a vast expanse of Arctic, complete with a group of polar bears waiting to catch some fish among the craters in the snow. But for now, the view on the ground around her was no less spectacular. The innocuous steel wire clothesline running across the garden had transformed itself into an elongated necklace of pearls, courtesy, the overnight rains; the spectacle however, was visible only to those who had that eye, the one that could see beyond the mundane.

Shweta sat at the edge of the veranda, comfortably in the high cane recline, draped in a bright red and black shawl. She rested against a fluffy cushion, sipping piping hot tea. This had been her favourite spot, a virtual gazebo, where she would sneak out, often in the morning, in the evening and during those golden winter afternoons. When others in the house would be busy with their daily routines, she would cherish her moments of solitude. The Murphy radio on the stool played on. Buzo sat under her chair, all curled up into a ball of wool. The tiny creature had been witnessing the first monsoon of his life. The previous night, he had been so scared that he had climbed on Shweta’s bed and lay nestled between her feet, burying his head a little deeper every time the skies roared.

The mild breeze had picked up a little in the last ten minutes, rattling the wind chime above Shweta’s head. The adolescent murraya, whose branches always danced with gay abandon in the slightest of breeze, stood unusually glum and still. Right then, a stiff breeze blew and in a sudden motion, the canopy drifted towards Shweta, like an umbrella whipped inside out in a gust of wind. Soon, Shweta was drenched with droplets of love. The murraya sapling had discovered this unique way of showing gratitude towards its saviour, one who had given it a second life. Such moments had always been of pure bliss, a feeling that Shweta had never been able to put into words.

It had been five years ago, on a hot May morning, when Shweta had located a tiny seedling, dry and wilted, inside the kitchen dustbin. On a momentary impulse, she had picked it up and ran to the garden. Using an old toothbrush, she dug a hole and planted the seedling. Its size was so small that it was sure to go unnoticed by everyone and trampled underneath careless steps. Moreover, there was that army of snails that raided the garden every night. Shweta had to ensure the safety of the seedling. So she had erected an insurmountable fence, by fixing empty shuttlecock boxes around. But having known Paltu, their gardener, well, she issued a stern warning to him, on the following day, not to dare uproot that little form of life nor fiddle with the seedling guard that she had erected.

In the days that followed, Shweta became a loving care-giver, watering it thrice, caressing its tiny velvety leaves, patting its scanty roots to grasp the soil quickly and whispering words of encouragement into the imaginary ears of the pencil thin stem to stand erect quickly. When the sun became too harsh, Shweta shaded its delicate frame with her little blue umbrella. Paltu of course, had been cynical about Shweta’s efforts all the way and even laughed under his breath. But one day, her efforts bore fruit and the discarded seedling struck roots.

The wind subsided a little and the playful murraya came to a standstill. The garden in front had become a deep pool in which the fallen bell shaped nerium flowers floated like ships in a harbour, waiting to set sail. A pair of babblers sat on the thin cane fencing by the side of the flooded flower beds, probably discussing the difficulty they would now face in collecting their food for the day.

Having removed the wet shawl from herself, Shweta felt cold and requested Chandan to get her another shawl.

‘Could you please put this out to dry?’ she said handing him the wet shawl.

Meanwhile, her mother, Bina, in her peach and purple housecoat, hurried to the clothesline with a blue bucket overflowing with washed laundry. She had been harrowed and harried the whole of last week, devising ways and means of drying an ever increasing mound of wet and damp clothes.

Bina had a spring in her step today. Her excitement was understandable. Determined to make most of every minute of the dry and drizzle free hour, she hung all the clothes on the line, meticulously clipping them in a way that ensured they caught the maximum wind. Shweta watched her activities, with a resigned look. Every time a garment kissed the line, it caused a few of the pearl drops to fly off and disappear. And once the dreamy pearls disappeared, their retrieval was impossible. They were so delicate and magical, emerging out of nowhere on a hanging wire! The spectacle had an otherworldly feel that defied description! Shweta was dumbstruck.

Just then, All India Radio (AIR) interrupted its ongoing programme to relay a special weather forecast. There would be more rain; and more rain to Shweta meant a few more such spectacles in the offing.

Bina in the meantime had come to the veranda, carrying the empty bucket in her hand. Shweta, in a playful mood, asked her if she had noticed the many pearls she had spilled on the ground and crushed under her slippers. Bina’s face crumpled in horror. She lifted her left leg and examined the muddied blue sole and then swiftly did the same with her right.

‘Daydreaming, sweetheart?’ She then rubbed the sole of her slippers on the coir doormat, taking care not to soil the word ‘Welcome’ embossed in deep red. Shweta gave a faint smile and muttered, ‘I knew it, you will not find the necklace.’

About the Author

I do a bit of multitasking with varying degrees of success at different points in time. First and foremost, I am a full-time mother trying to keep two hyper-energetic kids under control! When the kids are off to school, I am a government officer, burying my head in files old and new! On weekends and other holidays, time permitting, I am a bird watcher and nature enthusiast who loves to walk literally in the woods following a bird call! And last but not the least, I dream to be a big-time writer too!

Reading and writing give me a lot of joy. I have grown up reading Ruskin Bond, the master storyteller. He is an amazing writer whose books are deceptively simple but are such a delight to read. When I start writing, I begin to live with my characters. I literally laugh with them and cry with them while writing.

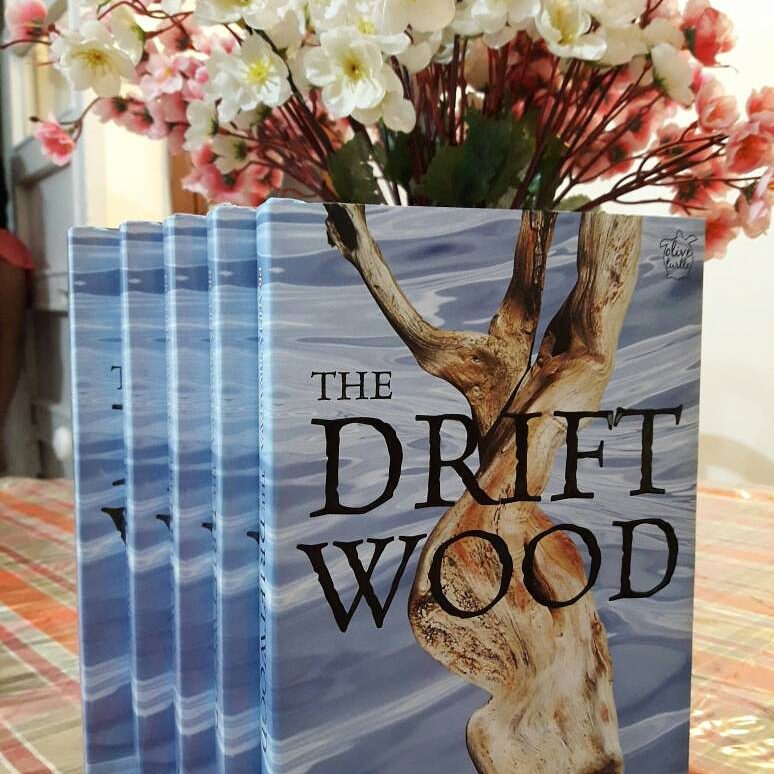

The Driftwood is my second book and has been published by Niyogi Books.

(Contributed by Pratima Srivastava, author, The Driftwood, Niyogi Books)

Editor’s Note: Excerpted with permission from ‘The Driftwood’, by Pratima Srivastava. It is reproduced as received. Different Truths has not edited it.

Publishers, authors or literary agents may please send Book Extract (fiction and nonfiction in the English language), in not more than 3000 words, including Author’s Bio. Send it to different.truths2015@gmail.com, marking Book Extract in the subject line.

©Pratima Srivastava

Pictures by the author

#BookExtract #BookClub #Author #Fiction #Writer #Driftwood #PratimaSrivastava #DifferentTruths