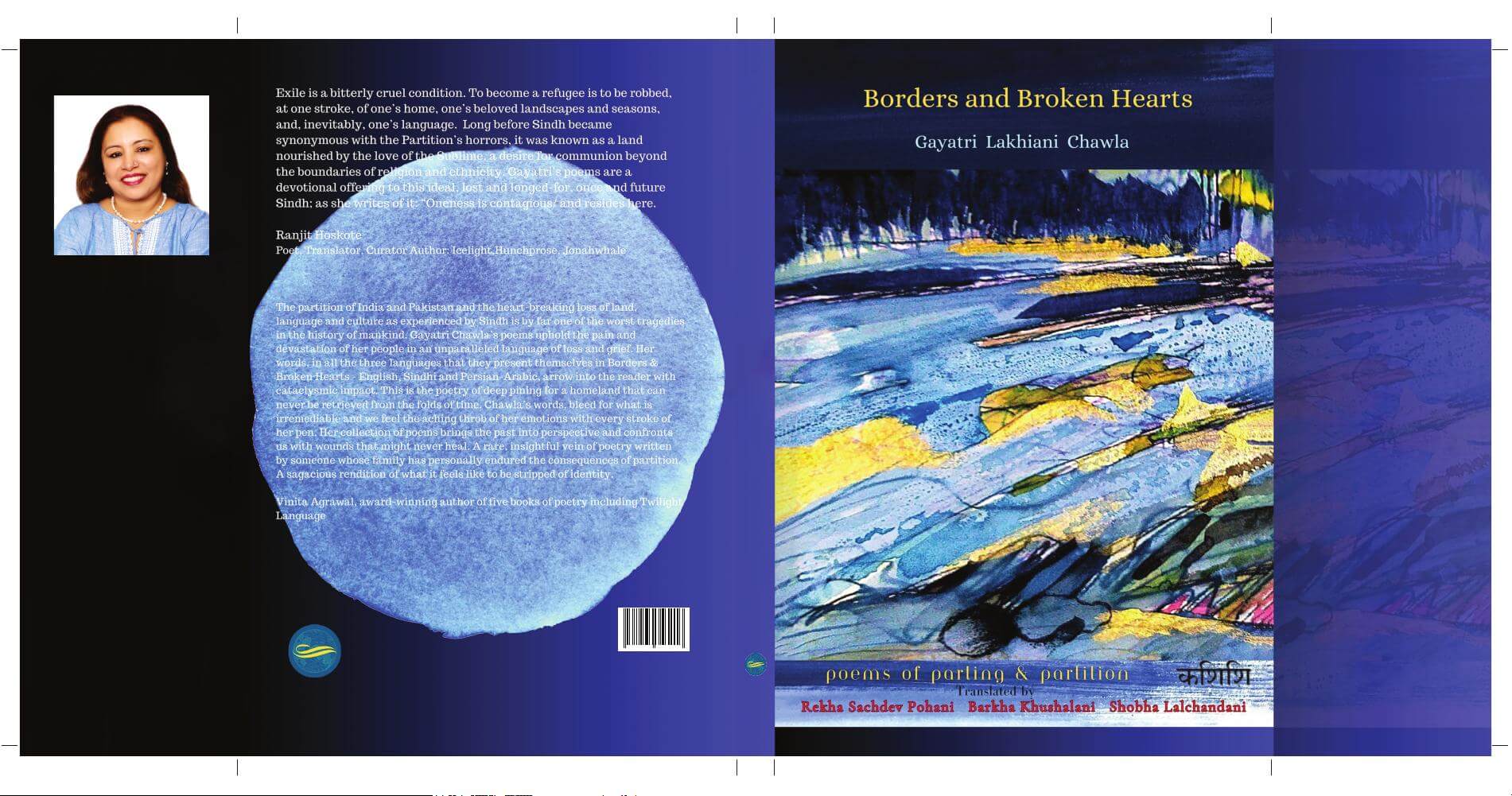

Mohan’s review of Gayatri Lakhiani Chawla’s Borders and Broken Hearts highlights the impact of partition on Sindhi literature, highlighting challenges like language loss and heritage preservation, exclusively for Different Truths.

In the aftermath of the partition of the country, those budding writers who had seen the bloom of their youth in Sindh continued writing in India, having a background of Sind and characters they had befriended while in Sind. A few novels and autobiographies are split between life in Sindh and in India. A novel by Sundri Uttamchandani, ‘Kirandar Deewaroon’ (Crumbling Walls), and the autobiography of Popati Hiranandani are such examples. Whereas Gobind Malhi’s novel, “Pakhiara Walaran Kahan Vichcrya” (Birds separated from flock), mainly has Sindh as a background. Sindhi poet Lekhraj Aziz, when asked to file a claim for the property left behind in Sindh, proclaimed, “My property is Sindh itself; I have a claim on the entire Sindh.” Narayan Bharti, with his two stories ‘Dastavez’ and ‘Claim’ about the peasants in Sind, set the nostalgic trend in Sindhi literature that continues till this day, cutting across various other literary trends ranging from ‘Progressivism to Postmodernism’.

Having lost the utility aspect of the Sindhi language in India, two generations in India grew up who had lost their original Sindhi language and were oblivious about the glorious literary and cultural history. Paradoxically, all this happened when the movement for inclusion of Sindhi in the 8th schedule of the Indian Constitution, led by eminent writers, intellectuals, and socially conscious elites of the community, took steps to save their rich heritage. This paradox was evident to some intellectuals even at the early stage, and through translations of contemporary and old literature, they tried to create awareness in the emerging generations of the community. This endeavour was aimed at acquainting the intellectuals of other communities with the heroic efforts of Sindhi writers about creative work being done in Sindhi, in spite of the calamity of partition and resultant uprootment. The first attempt was made as early as 1959, when Hashoo Kewalramani brought out an English translation of Sindhi Short Stories. (A second enlarged volume was published.) In the case of poetry, in collaboration with Arjan Shaad, Menka Shivdasani and Anju Makhija brought out Freedom and Fissures, published by Shaitya Akademi in the year 1998. Popati Hiranandani wrote’ Scattered Treasure’. Sindhi Folk Tales were also translated into English. It is heartening to note that many such efforts are afoot.

We had started to build a bridge to enable ‘lost’ generations to come back, and now it is very encouraging that, as no bridge is one way, there is traffic from the other side also. It was a pleasant surprise to come across a book by Sindhi origin, Gayatri Lakhiani Chawla, who has been writing poetry in English translated into Sindhi. Original English poems have been written by a talented poet, Gayatri Lakhiani Chawala, and have been translated into Sindhi by a trio of Rekha Sachdev Pohani, Barkha Khushalani, and Shobha Lalchandani. The volume consists of 25 poems. The Sindhi translation of the book has been published in three scripts. Sindhi (Persio-Arabic) script, Devnagiri script, and Roman script (perhaps for the benefit of the Sindhi Diaspora). Most of the poems in this book clearly express a desperate craving to connect to cultural roots.

Her first poem ‘Leaving Sind’ starts thus:

Occasionally I fell the loss/of place / of inheritance of a homeland’ ...’ Occasionally I feel like an island/an unnoticed speck/a lost postcard/with no address/sitting in the Post Office/with a stamp reading “Undivided India”.

Her poem ‘Terminal” is about Sindhi snack ‘papad’: Sitting in the corner balcony of his one bedroom/early mornings he is busy/the ten kilo papad dough needs kneading/handful of spices must be showered/and then there are spirits of solitude/from his backyard in Karachi.

Interestingly, the making of the snack used to be a collective neighbourhood activity where the women would come together to roll and flatten thin the papads and leave them to dry on cots on the terrace of the house.

In the same poem there is a reference to a talisman:

From the age of five/he wears a talisman/copper metallic plate/cold like the dead body of the cobra/coiled, de-composed, melted salt/Death is a great leveller.

The use of the word ‘talisman’ symbolises the composite culture of Sind that was permeated by Sufi ethos.

In her poem Hiraeth:

That summer we left out childhood behind/in the darkling orchard/before we knew it/the julienne carrots and turnips/left to sour and pickle/in the scorching sun/before we knew it

She explains that the word ‘Hiraeth’ is a Welsh word for nostalgia and home sickness.

The mass exodus from the native soil is described in ‘Flight 1947,’ and the expression ‘an oyster of teardrops’ makes it poignant.

Jamshed Quarters stands tall and stoic/the lights have been switched off/I look away a sea of fragments/ahead, an oyster of teardrops.

In her poem ‘Sindhi’ she talks about Sindhi language, she confesses and bemoans that loss:

My language is alien/alien to me’ and feels that ‘gold stories beaded around my neck/a gift from my grandmother/ My language is alien/alien to me’.

I have often said that while in India we have built many houses, but we do not have a home. A home that provides a sense of security like that of a fort, or in more extravagant terms, a castle. In her poem ‘Home’ she concludes:

‘Quite, like the Sindhu/wreaking a secret storm/ our lives remain connected/ and so do we’.

She has written some poems based on the folk tales of Sind ‘Moomal Rano’ and ‘Sasui and Punhoon’ that are quite pithy.

From her poem Sasui and Punhoon:

‘Punhoon peers to see his reflection/only to find his lissome Sasui/The truth frees you/Much like the rain.’

Her other poems in the collection contain expressions invoking powerful imagery, and she has an art of deft handling of words. The present collection is proof enough that the poet has a potential and promising future ahead.

This book comes as a promise of such ventures in the future, where more literature written by Sindhi-origin writers in English or any other language is translated into Sindhi to enrich Sindhi literature and Sindhi literature is translated in English and other languages to make them aware of the strong Sindhi literary tradition. It sets a fine example of literary exchange cutting across language barriers.

Cover image sourced from the author

By

By

By

By

By

By