Long Day’s Journey into Night, currently being staged at Los Angeles, is a masterful rendition of Eugene O’Neill’s masterpiece about the human condition. The British cast is led by the venerable Jeremy Irons. The approximately 3.5-hour play is the stuff of Greek tragedy and Shakespearian drama, following the descent of the Tyrone family into the long night of the soul. Here’s a review, for Different Truths.

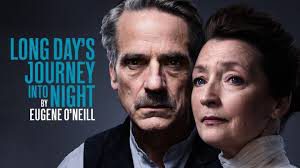

The Bristol Old Vic Production of Long Day’s Journey into Night, currently being staged at Los Angeles, is a masterful rendition of Eugene O’Neill’s masterpiece about the human condition. The British cast is led by the venerable Jeremy Irons, who won an Oscar for 1990’s Reversal of Fortune, and Lesley Manville, who was Academy Award-nominated this year for portraying Daniel Day-Lewis’ sadistic sister in Phantom Thread.

The approximately 3.5-hour play is the stuff of Greek tragedy and Shakespearian drama, following the descent of the Tyrone family into the long night of the soul. All of the onstage action is set at the Tyrones’ coastal cottage in Connecticut, where the fog rolls in and out and a foghorn sounds in the background. Joining James (Irons) and Mary Tyrone (Manville) are their sons, James Jr. (Rory Keenan, who has appeared often at Dublin’s fabled Abbey Theatre) and Edmund (Matthew Beard), who proceed to tear one another—and their selves—to pieces, like birds of prey in a familial feeding frenzy over faults and flaws, real or imagined.

O’Neill’s searing semi-autobiog raphical play, originally presented in four acts, roughly follows the Aristotelian unities of time, place and action. The family is afflicted by substance abuse problems in the form of morphine and liquor that grow out of troubles such as Mary’s sense of rootlessness and lack of a sense of home. Of course, like many lonely people who have the habitude of solitude, she routinely (if blindly) pushes people away from her: Man (and woman), his/her own prison maketh.

raphical play, originally presented in four acts, roughly follows the Aristotelian unities of time, place and action. The family is afflicted by substance abuse problems in the form of morphine and liquor that grow out of troubles such as Mary’s sense of rootlessness and lack of a sense of home. Of course, like many lonely people who have the habitude of solitude, she routinely (if blindly) pushes people away from her: Man (and woman), his/her own prison maketh.

The early death of their little son before the curtain lifts causes Mary untold woe, and she blames her older son, Jamie. Intriguingly, O’Neill calls the unseen, lamented lad “Eugene”—which of course is his own name. Like Edmund, O’Neill was beset by health problems and the play is full of other self-reflective themes: Years spent out at sea (poetically recounted by Beard as Edmond); growing up in hotel rooms as the son of a stage actor, like both Tyrone boys; a penchant for John Barleycorn; and more.

Often, on screen, stage or page one has no idea why the dramatis personae behave the way they do. But one of the great things about O’Neill’s writing, helping to account for the length of the aptly titled Long, is that he fully develops his major characters’ back stories, which explains what makes them tick. For example, Irons movingly reveals what made James Tyrone, a successful actor, so miserly and so unwise to invest in real estate. Worst of all, his penurious childhood is the reason why he squandered his promising theatrical career on a surefire hit; James comes to rue selling his artistry out for commercial reasons. When the cheap father blurts out “Let it burn!” in order to humor his ailing son, it is a thrilling line wherein a character momentarily overcomes his flaws, reaching inward for a higher self.

(Interestingly, although Long was written shortly before the author’s daughter Oona O’Neill met Charlie Chaplin, James’s being a tightwad due to his poverty-stricken childhood is similar to what has been said about Chaplin. The by then not-so-Little Tramp was old enough to be Oona’s father when they wed in 1943).

During a 2015 press conference at the Zurich Film Festival for the artsy film, The Man Who Knew Infinity, Irons was asked why he acts in small low budget movies, as well as in blockbusters such as the Batman series as the butler Alfred. The now almost 70-year-old actor pointed out that doing big-budget Hollywood flicks enables him to continue his pursuit of challenging roles in artistic works, presumably such as Long. It’s reassuring to see an actor who has attained Mr. Irons’s heights stick to his artistic guns.

The cast is simply splendid in their heartbreaking beauty. Richard Eyre brilliantly directs the ensemble in an eye-catching, book-filled set designed by Rob Howell, with moody lighting by Peter Mumford. This production is a British import (by way of Brooklyn’s BAM) of the venerable, 250+-year-old Bristol Old Vic Theatre, with the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts in association with Fiery Angel and associate producer Padraig Cusack.

The playwright was the son of an immigrant actor from Ireland, and James Tyrone says he crossed the Atlantic from the Emerald Isle when he was only ten. Irons, who trained at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School and became a member of the company half a century ago, was born on the Isle of Wight off the English coast. So his accent can be explained, as can the amiable Irish servant Cathleen’s (Jessica Regan) brogue. Manville and Keenan sounded like Americans to my Yankee Doodle ears.

The one flaw I’d find in this almost peerless version is that Beard, a Londoner, does not fully succeed in overcoming his accent playing the American Edmund. This is, however, a mere quibble: He is otherwise excellent as the tortured sensitive soul who loves to read and rhapsodize about going out to sea. In one Long scene, he appears barefoot and Beard’s expressive, lanky feet can act most thespians under the table!

Early, in Act I Edmund’s waxing philosophical prompts his self-made father to deride his son as a “socialist” and “anarchist.” The allusion is to O’Neill’s own lefty background, hobnobbing with John Reed and Louise Bryant, who were depicted in Warren Beatty’s 1981 Reds (Jack Nicholson portrayed Eugene in the Russian Revolution epic). O’Neill’s 1922 play The Hairy Ape dealt with almost slavery-like labor exploitation on the high seas, and in his youth, it’s believed, Eugene joined the Wobblies. The year 1920 play, The Emperor, Jones considered race-related issues, and none other than Paul Robeson starred in its 1933 screen version.

In the J.D. Salinger 2017 biopic Rebel in the Rye, Eugene’s daughter Oona O’Neill (Zoey Deutch) delivers a devastating line about her absentee father. I have interviewed two of Oona’s sons with Charlie, including Eugene Chaplin, named for his famous grandfather, and a great-grandson. Unfortunately, while the Nobel Prize Laureate and multiple Pulitzer Prize-winner may have written with great insight and illumination about the human condition, he does not seem to have been able to apply his wisdom to his own private family life. He may have won literature’s and drama’s highest accolades, but as a father, alas, O’Neill appears to have been a flop—at least to Oona.

Having said that, this bravura production of Long Day’s Journey into Night spearheaded by the virtuoso Irons is among the best tragedies I have ever seen. It is a must-see for all lovers of great acting and drama.

E D Rampell

The writer is a Los Angeles-based film historian/critic and co-organiser of the 70th Anniversary Commemoration of the Hollywood Blacklist.

©IPA Service

Photo from the Internet

#LongDaysJourneyIntoNight #Theater #Play #StagePerformance #Review #DifferentTruths

By

By

By

By