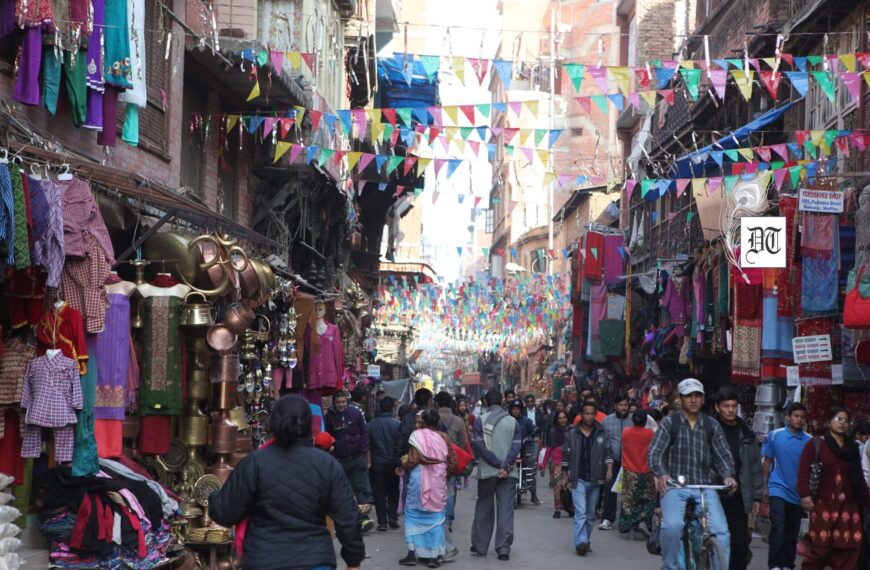

Journalists were puzzled by what the followers of Muqtada al-Sadr and the Iraqi Communist Party (ICP) might have in common, and even more, by why they garnered more Iraqi votes than any other electoral list. Al-Sadr’s Mahdi Army fought the U.S. early in the occupation, and his political base is mostly among poor and disenfranchised Iraqis, especially in Baghdad’s Sadr City. A report, for Different Truths.

The U.S. media quickly dismissed the results of Iraq’s national elections on May 12. Journalists were puzzled by what the followers of Muqtada al-Sadr and the Iraqi Communist Party (ICP) might have in common, and even more, by why they garnered more Iraqi votes than any other electoral list.

Al-Sadr’s Mahdi Army fought the U.S. early in the occupation, and his political base is mostly among poor and disenfranchised Iraqis, especially in Baghdad’s Sadr City. This vast neighborhood of 3.5 million people, half the population of Baghdad, was known originally as al-Thawra, or Revolution, built for poor people migrating from the countryside by radical nationalist Prime Minister Abdul Karim Qassim in 1959. For many years it was a stronghold of the ICP. Later, after the Baathist coup that overthrew Karim Qassim and eventually brought Saddam Hussein to power, it was renamed Saddam City. Then, after the 1999 assassination of Muqtada al-Sadr’s father, Ayatollah Mohammad Sadeq al-Sadr, it became popularly known as Sadr City.

The New York Times labeled Muqtada al-Sadr’s partners in the Sairoon coalition “Iraq’s moribund Communists, Sunni businessmen and pious community activists.” Actually, besides al-Sadr and the ICP, Sairoon (meaning Forward or the Alliance for Reforms) includes the Youth Movement for Change Party, the Party of Progress and Reform, the Iraqi Republican Group, and the State of Justice Party.

Oversimplifying politics and ignoring history, however, is not just a matter of names. It reveals the blindness to the long process in which Iraqi civil society has been rebuilding itself, to the popular anger that has motivated this, and to the growing support for the political alternative this alliance proposes.

The 329 parliamentary deputies chosen in the May election will vote for a new prime minister. Sairoon won the most 55 deputies, with 1.3 million votes. It was followed by the Fatah Party of Hadi al-Amiri, whose base rests on militias with ties to Iran, with 47 seats and 1.2 million votes. Voters rejected the parties of both the current Prime Minister Haidar al-Abadi (Victory Coalition with 40 seats) and former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki (State of Justice Party with 25). Turnout was low, at 44 percent nationwide and only 33 percent in Baghdad itself (where Sairoon won 23 percent, almost twice that of any of its rivals).

The program of the Sairoon alliance calls for an end to the system that divided political positions and government support along sectarian lines, a system imposed by the U.S. after its occupation of Iraq in 2011. Basing a governmental structure on sectarian political parties led to a system of patronage and division of spoils, and consequently enormous corruption. Al-Sadr explained, “I’ll say this despite the amama [turban] on my head. We tried the Islamists and they failed miserably. Time to try independent technocrats.”

Sairoon also called for independence from foreign domination by the U.S. and Iran. In advance of the election, a senior Iranian politician, Ali Akbar Velayati, visited Iraq and threatened Iranian reprisals if voters chose Sairoon: “We will not allow liberals and communists to govern in Iraq,” he said. Many secular politicians condemned the statement as interference in Iraq’s internal affairs.

Following the election, because no group got anywhere near a majority, negotiations began between Sairoon and two runners-up, al-Amiri’s Fatah bloc and al-Abadi’s Victory Coalition. Inside Sairoon this has produced tension between the Sadrists and the ICP. Some coalition members are calling for it to go into opposition rather than agree to power-sharing with parties and politicians still committed to the hated sectarian quotas.

ICP’s general secretary, Raid Jahid Fahmi, however, says the Sairoon alliance has a strong natural basis. “The social base is quite close-the social base of the left and the social base of the Sadrist movement,” he explained. In the Shiite holy city of Najaf, one of the country’s most conservative, voters elected a Communist woman representing the Alliance. Suhad al-Khateeb, a teacher, anti-poverty, and women’s rights activist, explained, “We were never agents for foreign occupations. We want social justice, citizenship, and are against sectarianism, and this is what Iraqis also want.”

The coalition is more, though than an agreement between Communists and Sadrists. It developed from a popular civic movement on the Iraqi streets, with roots in protests going back to 2010, and in the growth and popularity of the country’s unions.

On May 18, just after the election, the Iraqi government announced that it would not only include all 30,000 contingent contract workers in the electricity industry in the Social Security system but would guarantee the same rights as those enjoyed by permanent workers to the 150,000 contract workers throughout the public sector.

Hashmeya Alsaadawe, president of the Basra Trade Union Federation and the electrical union-the first woman to head a national union in Iraq-said that the elections had encouraged people to demand that they benefit from the country’s oil wealth. “Workers have high expectations,” she said. “They have been very active in demonstrations and on social media to demand their rights.”

Those heightened expectations and worker demonstrations dealt a blow as well to the World Bank, which had threatened the Iraqi government that it would not grant critical loans without reduced government spending on social benefits. Under bank pressure, last year the Iraqi cabinet then approved a draft social security law that would have increased worker contributions to the funds while raising the retirement age from 63 to 65. “Adoption of this draft will lead to increased poverty among Iraqis, even though they are living in one of the world’s richest countries in oil,” Alsaadawe charged.

Workers in the critical oil and gas industry in December finally formed a national network of eight previously competing unions. According to Hassan Juma’a, “One of the most important priorities is the unity of the trade union movement in Iraq. We have started the first step in the most important sector, the oil and gas sector. This network gives us a unified force capable of defending workers’ rights and protecting national production.”

The network’s objectives include defending the rights of contingent and migrant workers, who make up a significant part of the industry workforce. Its nationalist spirit is evident in its commitment to “protect national wealth for future generations against capitalist companies that do not respect the rights and opinions of citizens,” and “to urge foreign companies to take responsibility for maintaining the infrastructure of areas near oil fields exposed to toxic emissions.”

Iraq today has six union federations. One, the General Federation of Iraqi Workers, is allied with the ICP, and another, the Federation of Workers Councils and Union in Iraq, was organized by members of the Iraqi Workers Communist Party. The country’s main oil workers union, the Iraqi Federation of Oil Unions, is independent. The Kurdistan United Workers Union united Kurdish unions in 2010, and the other two federations are smaller groups that existed under Saddam Hussein.

Iraqi unions and federations do not bind their members to support of individual political parties. According to Wesam Chaseb of the AFL-CIO-linked Solidarity Center, “They are the real face of Iraq. There is no discrimination among workers.” Unions do not use the candidate endorsement system used by U.S. unions, but some individual union leaders also play roles in political parties, and unions encourage their members to vote for candidates who support workers’ demands.

Dhiaa al-Asadi, the director of Muqtada al-Sadr’s political office, told the Al-Monitor news website that the Sairoon list is “a reform project that represents the hopes and expectations of deprived and less advantaged people. This project of Sairoon constitutes a paradigm shift and a departure from the established norms that have characterized the political process since 2003.”

This combination of street protests, electoral activism, and increasing union strength is one of the most important features of Iraq’s political landscape, as Iraqis seek to rebuild their country after four decades of war, the deaths of millions of people, and a bitter decade of foreign occupation and domination. A growing progressive alliance, recovering its oil wealth, could make Iraq a country to be envied by its neighbors instead.

David Bacon

The writer is a California-based leftwing journalist

©IPA Service

Photo from the Internet

By

By