In the second and final part of the research article, Amit, our Editor-at-Large (Europe) examines the methods of Testimonial Therapy (TT) to generate the human rights movement. He tells us about the four stages of TT, rehabilitation and mobilisation, and the social theories at play. These help the Dalits to move from torture to dignity. A Different Truths exclusive.

PVCHR investigates and documents human rights violations, and, in cases of custodial torture, also provides legal aid. The main objective of the PVCHR project was aimed at rehabilitation of torture victims through testimonial therapy[1], grass root mobilisation of marginalised- particularly Dalit community of Mushars. With the help of Danish NGO, PVCHR started to work on rehabilitation of police torture victims who mainly belonged to Dalit’s Mushar community. In 2010, Danish organization (RCT) in a human rights workshop related to testimonial therapy, trained local human rights activist belongs to PVCHR. The project area was in the state of Utter Pradesh located in the district of Varanasi.

Testimonial therapy is a method of healing adopted for torture survivors in India.

“The testimony is truth-telling and emotion-pain sharing of the survivors with which truth is an important aspect of the justice process. The testimony is viewed within the broad framework of social construction and provides valid information on human rights violations without humiliating the witness… They regain self-esteem through the recording of their stories in a human rights context, as such; private pain is reframed with a political meaning (Raguvanshi, Praveen & Khan, p.29, 2015).”

Testimonial therapy includes four sessions:

In the first two sessions, community workers assist survivors in the writing of their testimony, which is their narrative about human rights violations they have suffered. In the third session, survivors participate in an honour ceremony in which they are presented with their testimony documents. In the fourth session, community workers meet with the survivors for a revaluation of their well-being. The honour ceremonies developed during the action research process came to employ different kinds of symbolic language at each site such as human rights in India (Agger, Igreja, Kiehle, & Polatin, p.568, 2012).

Thus, the process of TT opens the possibility of one’s participation in a community. Testimonies provide a lot of subjective information about the plight of the victim which help the court to take into account when the bail application of the victim is considered. Human sufferings are never recorded in the court proceedings (Bose, n.d). However, these small references to human sufferings often help torture victim establish their cases against their perpetrator. Testimonies can be used as urgent appeals and advocacy work. PVCHR as part of their human rights advocacy, promote these testimonies on their blogs, NGO website, facebook, twitter. In addition, in their publication known as ‘Voice of Voiceless’ PVCHR publishes testimonies of torture victims which helps in the fight for social justice and visibility of raising the human rights cases in local, national and international level.

Rehabilitation and Mobilisation

Rinker (2016) has shown that emotional and social resonance of stories of past violence and the important value of such stories as agents of change. This is reflected in the impact of PVCHR project on torture survivor which develops a legal and emotional testimony; helped building “critical consciousness” among the torture survivors, also TT empowers torture victims to take legal action against their perpetrator. Of the 361 survivors involved in PVCHR/RCT’s project on testimonial therapy, 89 per cent of them are from scheduled caste backgrounds (Ibid).

After the project, torture victims were more informed about their human rights, were more assertive confronting police in case of their (or community members) human rights violations and to prevent any  potential unrest. Now, they organise their community meetings; fear of police has greatly decreased among them. Community members are aware of their human rights, particularly right not be arrested arbitrary and know the process to seek judicial recourse. Torture victims often work as a human rights defender for their community, generating awareness about their human rights awareness and monitoring the human rights situation of their groups. This has made difference to their lives. (Rahuvanshi, Praveen, & Khan, 2015).

potential unrest. Now, they organise their community meetings; fear of police has greatly decreased among them. Community members are aware of their human rights, particularly right not be arrested arbitrary and know the process to seek judicial recourse. Torture victims often work as a human rights defender for their community, generating awareness about their human rights awareness and monitoring the human rights situation of their groups. This has made difference to their lives. (Rahuvanshi, Praveen, & Khan, 2015).

Now, Dalit community members often participate in rallies, sit in and protest rallies if some injustices are met to their community. Police are more careful dealing with them and vigilant about protecting their rights. They regain self-esteem through the recording of their stories in a human rights context, as such; private pain is reframed with a political meaning. They understood that their case stories are important for human rights advocacy in various villages. At this level, the formation and mobilization of human rights movement at the grassroots level are apparent. Though, the language of social struggles invoked Constitutional rights, however, undertone was similar to the human rights. Due to the history of such social struggle in India, human rights discourse gained momentum –particularly in Women’s and labour rights movement in the 1980s. As Shivji (n.d.) well noted that the use of human rights shall be seen in the context of social struggle. In such grass-root social struggle, a new wave of human rights emerged (economic, social, cultural and right to development) and contributed to the discourse of human rights. The similar opinion is expressed by Rajagopal (2009) who believe that politics of human rights was in many ways generated by a range of social movements or ordinary people, not only by states and elites.

Usually, in two years of time, some torture victims after going through TT, have been transformed as a human rights defender, not only fighting for their human rights but also, supporting other torture victims from their community. Due to NGOs intervention; with their psycho-social and the legal support, grassroots mobilisation of the suffering community became possible where Mushar were able to break the culture of silence eliminating their age-old fear (pvchr.asia).

Their testimonies as a legal strategy, are used during the open hearing organized by National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) in Varanasi on 25 – 26 November 2013. This form of legal advocacy has been successful, not only get perpetrator police held accountable but also torture victims get reparation for abuses they have suffered at the hands of police. Their testimonies are read out in presence of villagers (these ceremonies are called honour ceremony, Photos of the ceremony can be seen on page 17, 18), NGO workers, local politicians and officials. In addition, local media are invited to cover an honour ceremony so the human rights injustice can be highlighted and government are put into shame (Raghuvanshi, Praveen & Khan, 2015).

The awareness against the prevalence of torture and organised violence (TOV) asserting their rights to be free from, is done through poster, pamphlet and flex-banners on various Acts, directives and guidelines issued by Supreme Court of India, National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), D. K Basu guideline, Scheduled Caste/ Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, Domestic Violence Act 2005 etc. It would be interesting to note activists drew on different levels of law (local, national, and international) throughout this process, however, the domestic law was significant in this case. Invocation on international human rights law was not prominent in PVCHR human rights advocacy.

Social Theories at Play

Four Dimensions of Social Movement and Epistemology of South

Within the social struggle generated by PVCHR, four dimensions of social movements – political opportunities, resource mobilisation, framing, and culture and identity — are visible and interconnected as suggested by McCann (cited in Tsutusi, p.882, 2012). Political openness – particularly a vibrant Indian civil society propagating human rights supported by the human rights inspired Indian Constitution to pave the path for such social movements; it also involves international network and their support for domestic human rights struggles.

In the case of PVCHR, Danish NGO funded and provided training support to human rights activist working  for PVCHR. Had it not been for transnational resources, PVCHR could not have run the project. In addition, testimonies of the torture victims were framed in such a manner, that not only appeals to the Indian authorities but also its foreign donor and international human rights audience; PVCHR post testimonies on its website which is widely accessed by the Western audience including foreign donor and international human rights network. International NGOs networks such as Forum-Asia, Organizations against Torture support PVCHR work.

for PVCHR. Had it not been for transnational resources, PVCHR could not have run the project. In addition, testimonies of the torture victims were framed in such a manner, that not only appeals to the Indian authorities but also its foreign donor and international human rights audience; PVCHR post testimonies on its website which is widely accessed by the Western audience including foreign donor and international human rights network. International NGOs networks such as Forum-Asia, Organizations against Torture support PVCHR work.

Due to this interplay between human rights stakeholders, grassroots social movement domestically may be influenced and so are their human right strategy for advocacy. They may completely adopt international human rights framework or with some modification including adopting local cultural elements; human rights framing fosters new subjectivities and cultures of rights (McCann, cited in Tsutusi, p.376-882, 2012). This trend is reflected in PVCHR careful use of testimonies for human rights justice and advocacy at local and national level. Testimonies reflect local cultural elements and a sense of injustice and pain.

It is to be noted, an impact of globalisation can be observed on social movement in the third world, where enhanced flows of resources for mobilisation, provides vocabularies for effective framing and facilitates the formation of social movement identity and actor hood (Tsutusi, 2012), however, globalization could discourage social struggle, too. It is to be noted that most Western NGOs provide funding support for protection of civil and political rights ignore economic, social and cultural rights. Western donors provide funding to NGOs according to their political agenda, not due to the necessity of third world countries. In case of PVCHR project, it was oriented to protect the civil and political rights as per their donor requirement.

In addition, the role of PVCHR in seeking justice for Dalits torture victims underscores the important role played by NGO as a translator, as Sally Merry (2006) would call them.

Sally writes:

Translators are both powerful and vulnerable. They work in a field of conflict and contradiction, able to manipulate others who have less knowledge than they do but still subject to exploitation by those who installed them. As knowledge brokers, translators channel the flow of information but they are often distrusted because their ultimate loyalties are ambiguous and they may be double agents.

In course of conducting TT and afterwards highlighting human rights violations of tortured victims, PVCHR played the role of translator, transmitting knowledge, learned from Danish NGO to Dalit’s torture victims. In this process, Dalits victims were vulnerable to manipulation (by NGO) since they were unaware of their rights, however, this did not happen in the reviewed case. Also, in course of seeking social justice, human rights workers of PVCHR (few times) were seen by some upper caste Hindu and Indian authorities with distrust and suspicions. However, the author of this paper is not aware if PVCHR is distrusted by any of the torture victims it worked with, as usually happen with the translators as Sally Merry (2006) claims. Within the TT system, the key translators were PVCHR human rights activist who was trained by Danish NGO. Although the participation of torture victims led them to stand up for themselves as human rights defenders, whether many have adopted core human rights ideas such as equality, autonomy and bodily integrity is questionable. The testimonies (and NGO record) of torture victims suggest that they participate in community mobilisation suggest that a few acquire a strong rights subjectivity.

Nevertheless, Sally Merry (2006) argues, that human rights must be translated into local webs of meaning based on religion, ethnicity, or place for them to appear both legitimate and appealing, translators must please their donors. As this Case analysis suggests, processes of vernacularisation are intimately connected to the interests of funders as well as those of local communities. Narrative of the torture victims was embedded with local cultural elements and traditions (as opening para of this paper shows, see part –I) in this manner it has local appeal, but also, when these testimonies go into the public sphere, attract, national and global attention.

Theoretical Implications for Epistemology of South

Narratives of torture victims represent a form of the epistemology of South – a language of resistance against oppression, a medium to fight against injustices in post-colonial society. As Santos (p.18, 2016) believe that Colonial domination and oppression still continue in post-colonial societies (such as India) in other forms of domination such as a Capitalism and patriarchy. For Santos, South is a metaphor for human suffering caused by capitalism and colonialism on the global level, as well as for the resistance to overcoming or minimising such suffering.

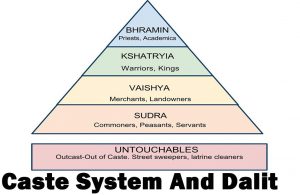

It is, therefore, an anti-capitalist, anti-colonialist, anti-patriarchal South. As we can see in case of torture victims, domination never act as pure forms but rather in a constellation of oppressions (Santosh) such as victimisation by police, discrimination by society. In addition, the practice of torture embedded in the Colonial legacy of Indian police has been employed to reinforce exiting Caste system, therefore, subjugation of millions of Dalits and vulnerable groups. (As prison statics suggests[2] majority of inmates/under trials is from lower Castes and religious minorities).

It is, therefore, an anti-capitalist, anti-colonialist, anti-patriarchal South. As we can see in case of torture victims, domination never act as pure forms but rather in a constellation of oppressions (Santosh) such as victimisation by police, discrimination by society. In addition, the practice of torture embedded in the Colonial legacy of Indian police has been employed to reinforce exiting Caste system, therefore, subjugation of millions of Dalits and vulnerable groups. (As prison statics suggests[2] majority of inmates/under trials is from lower Castes and religious minorities).

Marginalised groups of Dalits systematically suffered injustices, dominations and oppression caused by capitalism, and patriarchy; their narratives are the ways of knowing from their perspectives of pain, justice, and human rights. It’s also a way/medium of the transformation of their social emaciation (as Santosh would observe) which crystallised their lives in their narratives and in honour ceremony. The South is rather a metaphor for the human suffering in of excluded, silenced and marginalised populations (such as Dalits in Indian case).

The concept of ‘epistemologies of the South’ provides a new base for understanding the social transformations- particularly in an unjust society (Santos, p.19. 2018). I see these narratives/testimonies as a framework for social emancipation/transformation challenging domination, capitalism, the hegemony of Caste, discrimination, and patriarchy in an Indian context. However, deep-seated structures and agencies such as structural discrimination/torture against Dalits, cannot be confronted by short-run interventionism (as Santosh suggests, p.19, 2016), however, require a ‘cognitive justice’ necessary for uprooting biases in mental attitude of majority; discrimination within dominant social-cultural discourse (including to stop systematic destruction of indigenous knowledge, what Santos calls epistemicide of Dalits knowledge) against lower Caste and prejudices in unspoken and implicit social behaviour of Upper caste Hindus- there would be no justice for Dalits without cognitive justice. The Hindu Brahminical system does not see scientific fervour in the indigenous knowledge of Dalits and tribal treating them as inferior. In order to eliminate discrimination against Dalits and vulnerable populations, upper caste must accommodate and respect their indigenous knowledge and traditions into mainstream knowledge and shall uproot biases prevalent in academic and religious discourse.

However, in this context, testimonies of victims (a kind of epistemology of south) offers a stiff resistance against the hegemony of caste; address the lingering legacy of the structural, cultural, and direct violence which is re-inscribed through torture. Testimonies develop a means of resistance, shows the failure of the government who did not respect and protect human rights of Dalits, activists employ testimony to challenge elite marginalization of Dalits and rewrite their place in the social life of Varanasi. Thus, an atmosphere of fear and impunity, PVCHR, with discreet use of TT, have played a vital role in generating social movement against the culture of torture affecting the vulnerable population of the Indian society.

Conclusion

This paper has discussed the role of an India based grassroots NGO using testimonial therapy as a tool for rehabilitation and human rights advocacy of Dalit’s torture victims. Paper shown in details how testimonial therapy has changed the lives of torture victims creating human rights awareness among Dalit’s and generating social movement against the culture of discrimination and torture. In addition, the paper also briefly discussed the four dimensions of the social movement (MaCann, 2006) and epistemology of south (Santos, 2002) in the Indian context. Along with, this paper attempted to contextualise idea of the translator in Indian NGO context as suggested by Sally Merry (2006).

References:

Agger, I., Igreja, V., Kiehle, R., Polatin, P. (2012) Testimonial Ceremonies in Asia: Integrating Spirituality in Testimonies Therapy For Torture Survivors In India, Sri Lanka, Cambodia and the Philippines, Transcultural Psychiatry, 49 (3-4) 568-589

Agger, I., Raghuvanshi, R., Khan, S., Polatin, P., Laursen, L. (2009) Testimonial Therapy A pilot project to improve psychological wellbeing among survivors of torture in India, Torture, Vol. 19, No.3

Bose, T. K (n.d.) Testimonial Therapy: A Path Towards Justice, Green Leaf Trust, accessed on 21 Feb. 18, available at http://www.academia.edu/2560102/TESTIMONIAL_THERAPY_A_PATH_TOWARDS_JUSTICE

Raghuvanshi, L., Parveen, S., Khan, S., (2015) Resilience-Based On Hope Honour and Dignity, Journal of People’s Studies, Vol.1, Issue 1

Rinker, J (2016) Narrative Reconciliation As Rights Based Peace Praxis: Custodial Torture, Testimonial Therapy, And Overcoming Marginalization, The Canadian Journal of Peace and Conflict Studies, Vol 48, Number 1-2

Khan, S (n.d.) We Can Change Any Thing With Unity, accessed on 21 Feb. 18, available athttp://pvchr.asia/anti-torture-initiative.php?id=232

Tsutsui, Whitlinger, & Lim. (2012) International Human Rights Law and Social Movements: States’ Resistance and Civil Society’s Insistence, Annu. Rev. Law Soc. Sci. 2012. 8:367–96

Goodale, (2007). Locating rights, envisioning law between the global and the local, in Goodale, M. and Merry, S. E. (orgs.), The Practice of Human Rights: Tracking Law between the Global and the Local. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 127.

Merry, E (2006). Transnational Human Rights and Local Activism: Mapping the Middle, American Anthropologist, 108(1): 3851

Narayan, B (2009) Fascinating Hindutva: Saffron Politics and Dalit Mobilisation, SAGE, New Delhi, 156.

Voice of Voiceless (2012), Vol.3. No. 1, accessed on 13 Feb. 18, available at https://www.scribd.com/document/106480311/Voice-of-Voiceless-May-2012

Voice of Voiceless (2011), Torture, Testimony and Right to Health, Vol. 2. No. 2, accessed on 13 Feb. 18, available at https://www.scribd.com/document/104045466/Vol-2-No-3http://pvchr.asia/

(Concluded)

©Amit Singh

Photos from PVCHR and the Internet

#CoverStory #HumanRights #Dalits #PVCHR #FightingForRights #RightssOfTheDalits #Advocacy #DifferentTruths

The ceremony of Testimonial Therapy, Source- http://www.academia.edu/2560102/TESTIMONIAL_THERAPY_A_PATH_TOWARDS_JUSTICE

Accessed on 21 February 2018.

Public Ceremony of Testimonial Therapy Source: http://www.academia.edu/2560102/TESTIMONIAL_THERAPY_A_PATH_TOWARDS_JUSTICE

[1] Survivors of Torture and Organised Violence (TOV) are prone to health disorders such as depression, anxiety, substance abuse and chronic pain.

By

By

By

By

By

By