Dr. Roopali tells us about the antiquity and splendour of the ancient city, Hastinapur. She meanders through its history, road, and contemporaneity. An exclusive for Different Truths.

In Sanskrit, Hastinapur means the City of Elephants. Hastina (elephant), and pur (city). This historical city is located on the banks of the River Ganga in the Meerut District of Uttar Pradesh in India. And it bears significance in many ancient texts.

The first reference to Hastinapur in the ancient Puranas speaks of the city as the capital of Emperor Bharata’s kingdom. It is described in texts such as the Mahabharata as the capital of the Kuru Kingdom of the Kauravas. It has also been known by other names in different ancient texts, and there are several historical reasons to believe that the city was named after King Hasti.

For those familiar with the Mahabharata, the name of the city will be familiar.

For those familiar with the Mahabharata, the name of the city will be familiar. Many events in this epic text are set in the city of Hastinapur. It is here, we are told, that the 100 Kaurava brothers were born to Queen Gandhari, the wife of King Dhritarashtra, the blind king. It is also here that the Pandava King Yudhishthira lost his four brothers and their common wife Draupadi in a game of dice.

Hindu and Jain Pilgrimages

Located on the banks of an old ravine of the Ganges, Hastinapur is one of the holiest places for Hindus and Jains. It is believed to be the birthplace of three Jain Tirthankaras.

… King Samprati, the grandson of the emperor Asoka the Great, built many temples here.

Our long history also tells us that King Samprati, the grandson of the emperor Asoka the Great, built many temples here. The ancient Hindu temples include Pandeshwar Temple and Karna Temple. The Jain temples are Shri Digamber Jain Mandir, Jambudweep, Kailash Parvat, and Shwetambar Jain Temple. Many renovated and reconstructed.

The Ain-i-Akbari – the 16th-century detailed document recording the administration of the Mughal Empire under Emperor Akbar – lists Hastinapur as a pargana under the Delhi sarkar. It produced a revenue of 4,466,904 dams for the imperial treasury and supplied a force of 300 infantry and 10 cavalries. The author, Emperor Akbar’s Court Historian Abu’l-Fazl ibn Mubarak, describes it “an ancient Hindu settlement” lying on the Ganges.

But during British times, Hastinapur was ruled by Raja Nain Singh Nagar…

But during British times, Hastinapur was ruled by Raja Nain Singh Nagar, who also built many Hindu temples in and around the city.

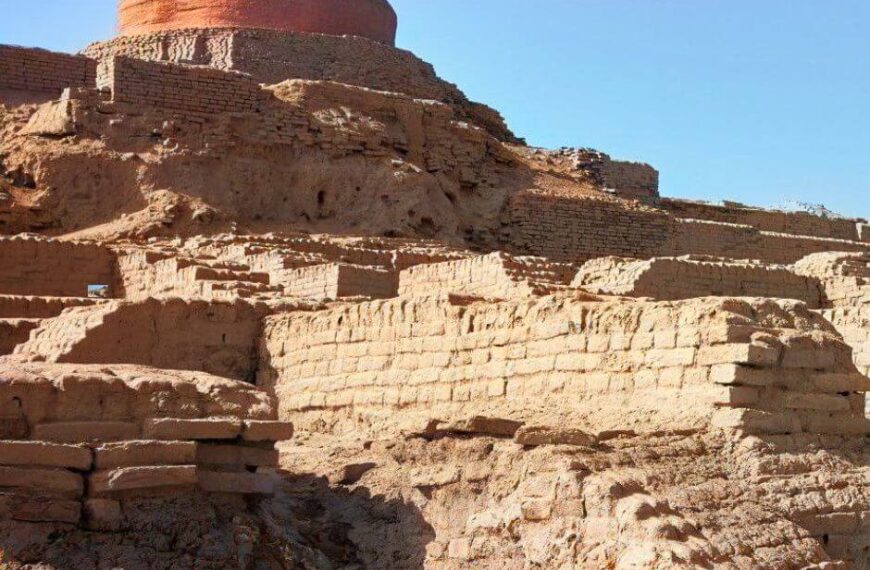

Survived History

Hastinapur is a city that has borne witness to and survived thousands of years of history. It has seen dynasties and regimes come and go. In the 1950s, the Archaeological Survey of India conducted excavations in Hastinapur. The excavation leaders were attempting to determine the position of ceramic ware from the early historical period. As they worked they began to discover correlations between the text of the Mahabharata and the material remains unearthed at Hastinapur.

Present-day Hastinapur is a bustling town in the Doab region of Uttar Pradesh…

Present-day Hastinapur is a bustling town in the Doab region of Uttar Pradesh, about 37 kilometres from Meerut, shy of a hundred kilometres north-east of India’s capital New Delhi. It is a township re-established by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru on February 6, 1949.

Today, after being at home during the pandemic of the last 18 months a friend and me, both fully vaccinated, donned our masks, and decided to visit Hastinapur. A smooth tarred road lined with massive trees took us toward this ancient city. The last of the monsoon showers drip-dripped as the wipers screeched clean the windshield, and the trees leaned across the road to touch each other.

Their verdant longing created an endless green roofed tunnel…

Their verdant longing created an endless green roofed tunnel, and we drove through this welcoming canopy all the way. Mango groves and fields of standing sugar cane and bright green paddy fields accompanied us for miles. The cool wetness filled with fertile thoughts.

Lost in Antiquity

Anticipation gripped us. This celebrated city was lost in antiquity.

What awaited us?

As we neared Hastinapur, we found roadside workshops of stone sculptures.

As we neared Hastinapur, we found roadside workshops of stone sculptures. Enormous horses with a king-like turbaned rider. Some bright orange Lord Hanuman statues; a few Buddhas in lotus pose rendered in wire and cement technique. The horses and riders looked familiar. I had met them before – in Rajasthan, on the way to Jaisalmer.

What was the connection here so far away?

A Mini Bengal

We stopped to learn more, and to take pictures. The sculptors and painters, we discovered to our surprise, were from Bengal. There is a ‘mini Bengal’ in Pilibhit, in the Neoria area there. Most of this 37,000-odd Bengali community of artists, artisans, fishermen and goldsmiths are Hindu refugees from Bangladesh (formerly East Pakistan), driven to take refuge in ancient Hastinapur 50 years ago.

They speak Hindi in a pronounced Bengali accent.

They speak Hindi in a pronounced Bengali accent. The older generation runs shops or sells fish. They only recall a torrential rainy day when they left West Bengal, and later, Bangladesh in the 1960s and 70s. They avoid talking about their departure.

Their votes now make or break election results. A respected community left alone to live in their own way, and to preserve their culture. They make a definitive artistic and political contribution to the abundant life around them. The Bengali fish market is a telling reminder of the live and let live nature of the very fabric of our society here in India.

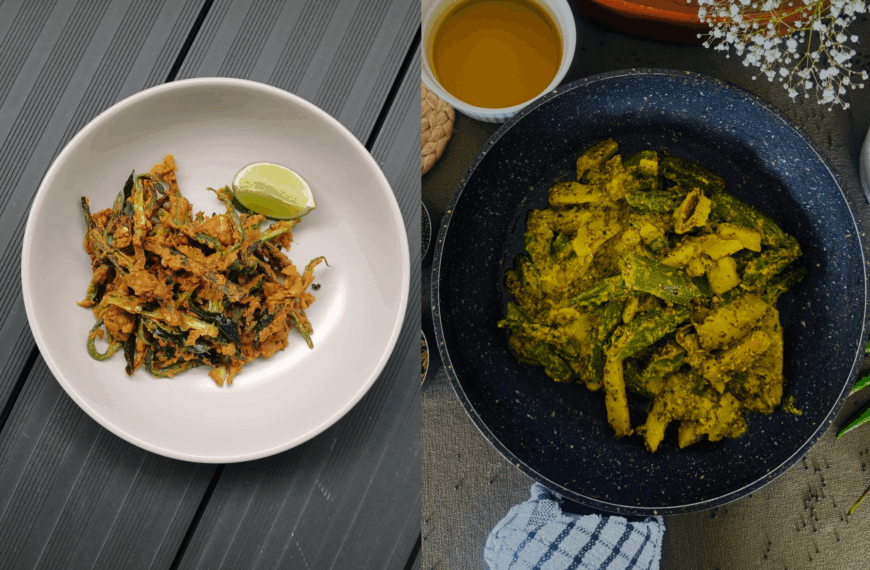

No hotels or roadside dhabas allow any food associated with the killing of animals.

Hastinapur is renowned for the birth of three of Jainism’s Tirthankaras. No hotels or roadside dhabas allow any food associated with the killing of animals.

Temples Everywhere

Old and new temples lie scattered everywhere. They all claim antiquity. Everywhere signs proclaim, pracheen mandir. Ancient Temple. There is also a place called Jumboo Dweep. It is a complex with many Jain temples, an ashram, a mini amusement park, a toy train and a stone elephant on wheels for kiddy rides.

Everywhere one looks, there are monkeys! Waiting for a morsel of food and some frolic.

Everywhere one looks, there are monkeys! Waiting for a morsel of food and some frolic. Covid-19 has taken away their free source of bananas and chapatis. And no humans to tease. But there are shops that sell peanuts and chanachur to feed the monkeys.

The exquisite carved marble marvels seen in Rajasthan’s Mt. Abu are not seen here. This is down to earth, removed from splendour. An unconscious effort to reclaim the past. Simple and austere. All physical traces of the hoary past seem invisible here. Yet there is a palpitating sense of the layers of centuries hidden somewhere. A collective consciousness of actions that seem not so long ago to have happened here!

A Quiet Connectivity

It is not what is created above the earth but what the earth contains matters. For my friend and me, Hastinapur exuded a quiet connectivity. It seeped into our being. A sense of déjà vu.

Young girls in school uniforms and backpacks full of books walked merrily in the rain.

We noticed the march of progress in Hastinapur. Young girls in school uniforms and backpacks full of books walked merrily in the rain. They are going to make history. They will re-write the rules of the game. No game of dice will decide their future. Rain or shine their determined strides tell us they are going to make it. That bit of wretched past will hopefully be put to rest.

Photos by the author

By

By

By

By