Meher, in this war zone story set in Syria, deals with the impoverished villagers, their hopes, fears, deceits, insecurities and more – exclusively for Different Truths.

Nabeel had never seen such a large mirror. He could see his whole body in it, from his black hair to his knees and ankles. He was tall, slim and, without the keffiyeh, a curly bunch of tangled locks sprouted over his head. He preened, flexed his arm muscles, stretched, bending forward to examine himself at different angles.

The mirror doubled the size of the hotel room: two beds, a wardrobe, and a small table with two chairs. The mirror duplicates everything. It felt strange to sit on a chair, even stranger to see himself sitting on a chair. He was used to sitting on the floor. He waved at his reflection; it waved back. He stuck out his tongue, and so did the reflection. Nabeel laughed, looking up at the rotating fan. It did not get doubled by the mirror.

A large window could open and shut, keeping the room full of light all day.

A large window could open and shut, keeping the room full of light all day. It opened to a busy street. Strange to be inside a room and see cars outside. Dozens of cars speeding in opposite directions. People calmly weave their way between them. Weren’t they afraid of getting hit? He saw a boy, not more than twelve, casually crossing the road. Could Nabeel do it?

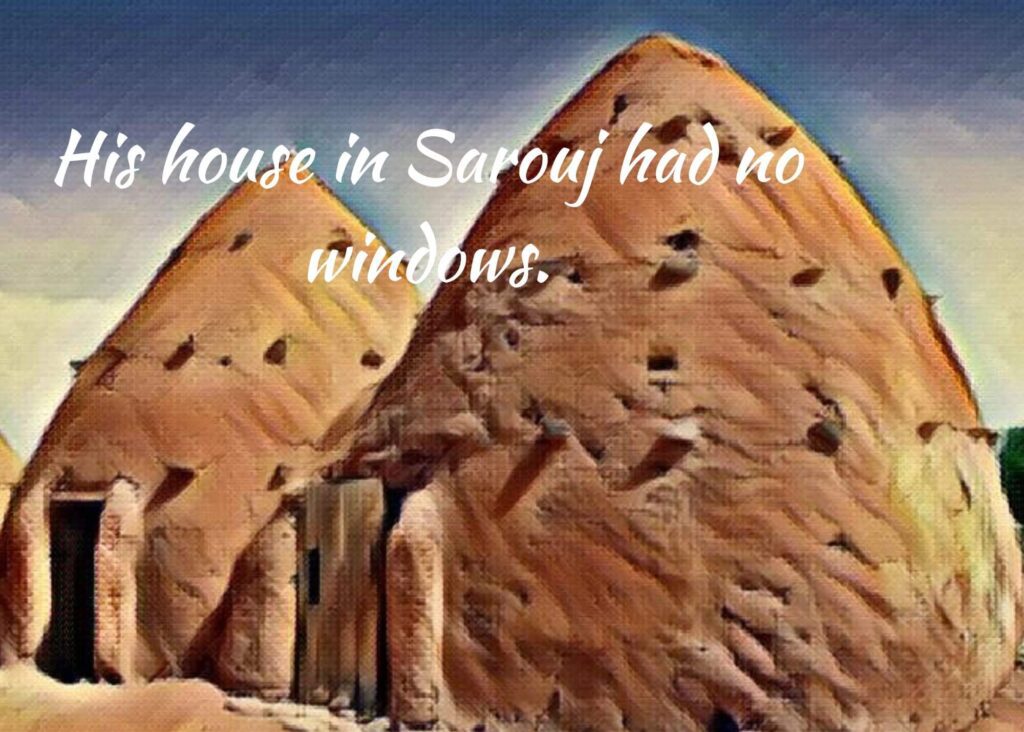

His house in Sarouj had no windows. All village huts were identical – conical ‘beehive houses’ topped by a dome, with small slits at the top letting in slivers of light. Inside it was dark but cool, contrasting with the desert’s blazing light. Thick walls of mud plastered over dry straw kept the heat out and protect residents from whirling sand.

His village was three kilometres from the highway. Only two buses serviced the area – one morning, one evening. Evenings were when his mother would spread her small rug outside their hut, chat with her neighbour, compare the price of dates, olives, and other paraphernalia at the souk, listen to the lilting flute of Sarouj’s oldest resident from the far end of the circular courtyard. On days the wind howled, flinging dust into their eyes; evenings ended before they began.

Nabeel had left it all behind. He was on his way to Greece with his Ammuh…

Nabeel had left it all behind. He was on his way to Greece with his Ammuh, entering a world where light and heat did not necessarily come together. Greece, with vineyards and fruit trees. Very different from fig trees and date palms. He had been dreaming of plucking an orange, biting into its juicy flesh all week. He was young and strong. He would get a job in Greece. In a factory, on a farm, or any job. The risky journey would be worthwhile.

Ammuh had gone to meet the agent fixing their journey. Bowa had sold off two milk-giving goats to pay for Nabeel. He had heard his father and uncle talking in low voices that it wasn’t safe for Nabeel to remain in Sarouj much longer. He had turned sixteen and was the tallest and strongest boy in the village. Militants had scouts prowling villages to suck away young men. Bowa wanted to keep Nabeel safe, even if he had to send him away.

Nabeel heard their decision with mixed emotions. More than Bowa, he would miss Daye. Who would he find waiting with a tumbler of goat’s milk when he returned from football? Who would wipe Daye’s sand-stung eyes with cold compresses if he was not around? Who would help her take down grain stored on the shelf, almost touching the roof?

But the idea of entering the modern world was exciting. He would work hard and send home money.

But the idea of entering the modern world was exciting. He would work hard and send home money. Once he was old enough to be no longer attractive to militants, he would return laden with gifts. He was excited to go with Ammuh, who had no sons and treated Nabeel as his own.

Ammuh had been gone three hours. Nabeel had enough of amusing himself with the mirror and the window. He was restless about stepping into the big city. To take on the traffic of the street. To begin his new life.

Deftly he wrapped the red and white keffiyeh around his head, leaving the right end dangling over his shoulder. Locking the room, he marched down the stairs leaving the key at the reception as he had seen an elderly man do when they checked in. Then he stepped into the sunlight, warm but not harsh.

A long straight road with attractive shop displays on both sides stretched before him. He walked along the pavement on the same side as the hotel. He would stay in sight of the hotel to be sure of finding his way back. Few people were on the road, but an eating house was full of men in kaftans tucking into succulent meats. Suddenly he felt hungry. Ammuh had told him to order lunch at the hotel but had not left money with Nabeel.

Though it was daytime, all shops were brightly lit with dozens of electric lights.

Though it was daytime, all shops were brightly lit with dozens of electric lights. Even a wedding in Sarouj didn’t have so many lights! What an array of goods! Clothes, shoes, bikes, luggage, copper bowls with shiny, geometric designs. Fancier than Daye’s, which were worn out with years of use. A plump woman was wearing a red knee-length skirt, her lower legs visible! Was she a tourist?

An unusual display on the opposite side of the road caught his eye. It was time to cross the street. Nabeel braced himself, stepped off the curb and dashed across, zigzagging between cars to jump onto the opposite pavement. Brakes screeched; drivers yelled, but Nabeel didn’t care. He was elated! He had done it! He was entering the modern world.

The enticing shop had mountains of colourful fruits. He had never seen so many varieties of fruit. How did such pyramids balance? If he ran off with one, would the pyramid topple? A man was buying bananas. As he lifted his kaftan for his wallet, a flash of steel glinted in the sunlight. A shiver ran down Nabeel’s spine. It was the butt of a handgun.

He had seen a gun only once. Two strangers had been mysteriously visiting Sarouj.

He had seen a gun only once. Two strangers had been mysteriously visiting Sarouj. They would come on the evening bus, go straight into Wahid’s house and leave by the next morning’s bus. They met no one except Wahid’s father. He could be heard arguing with them late into the night.

Wahid was three years older than Nabeel. They played football at the edge of the village in the hours before sunset. One night, voices were louder than usual, with the whole village hearing Wahid’s father repeatedly shouting, ‘No! I will not let my son go!’ A gunshot rang out. Then silence. Scared villagers remained behind locked doors.

Nabeel had been unable to sleep. Early morning, he climbed to the slim slit at the roof of their hut to see Wahid being led away by the strangers, one trying to press a gun into Wahid’s back. Was the man buying bananas one of those who had taken Wahid away?

Adjacent to the fruit stall was a supermarket with everything under the sun stacked from floor to ceiling – plastic packets, jars, and bottles labelled with names he could not read. Women in colourful hijabs, faces open to sunlight, picked what they wanted into little carts, wheeling them towards a counter where a cashier made bills. What a strange market. No one was bargaining!

He stepped into the sunlight again, making a quick turn to see if he could spot his hotel.

He stepped into the sunlight again, making a quick turn to see if he could spot his hotel. Yes, there it was, shrunken by distance but recognisable by a bright red signboard in a language he could not read. Two boys around his own age peered into a bookshop with Arabic titles. He passed a flower shop, a barber, and another eating house, less crowded than the first. Then the road divided. Both would take him away from the sight of the hotel. He had to turn back.

Why were two men with arms linked standing silently at the crossroads? They couldn’t be afraid of crossing. As if by magic, traffic stopped, and they strode across. Nabeel ran behind and was safely on the side of his hotel. Cars started moving again. He reminded himself he was in a modern city. Ammuh had told him about red and green lights.

Back at the hotel, Ammuh was sitting on the bed, rifling through sheaves of documents. In a high-pitched voice, Nabeel started prattling about the brightly lit shops, the lady with the short red dress, triumphantly adding that he had crossed the busy street twice! Slowly his uncle’s sombre mood seeped in. His uncle’s eyes were downcast; his body slouched, his keffiyeh flung carelessly on the chair. “Something wrong, Ammuh?”

Ammuh lifted troubled eyes to his nephew’s face. “I have to send you back to Sarouj,” he announced.

The words were a slap. He had barely touched the periphery of his dream.

The words were a slap. He had barely touched the periphery of his dream. How could it be snatched away! “Wh-what happened?”

In a breaking voice, Ammuh told him that the last boat the agent had sent out capsized because it was overloaded. Some people managed to swim; some got drowned. “He’s overbooked tomorrow’s boat as well,” concluded Ammuh ruefully.

“We must find a better agent.”

“He refused to return our money.”

“He must refund our money!” cried Nabeel indignantly. “Report him to the police!”

His uncle’s face took on a wry smile. “People like us can’t go to the police. We are travelling without papers. That’s why these sharks get away with it.”

They sat in silence, tension engulfing them in a palpable cloak.

They sat in silence, tension engulfing them in a palpable cloak. The mirror doubled their troubled faces. Nabeel had no eyes for it now. The turmoil in his head kept swirling like bees around a hive. How could he return to his cloistered home after just a few hours in the glittering city? Why should he give up dreams of a decent life? Risk getting dragged into danger again.

Ammuh’s voice cut through the fog. “Sorry, Nabeel, I have to send you back.”

“Send? You’re not coming?”

“I have enough money for only one bus ticket.”

“What about you?”

His uncle remained silent, eyes fixed on the floor. “I sold everything to pay this agent,” he said at last. “I have nothing left in Sarouj. If I go back, I’ll become a beggar. I have to go on the boat.”

Nabeel’s lip pursed in indignation. Life was unfair.

Nabeel’s lip pursed in indignation. Life was unfair. The contrast between Sarouj and the glittering city was proof enough. But an agent making money from people’s life savings was worse than injustice. It was criminal.

In a flash, Nabeel decided to join the police once they reached Greece. He saw himself in uniform, in a position of authority, cracking down on criminals. If, for some reason, he couldn’t do that, he’d become a guide, not an agent, helping refugees to cross over safely. Make sure no boats capsized; no people got drowned.

“I am coming with you,” said Nabeel decisively. “We left Sarouj together; we will be safe together.”

Ammuh shook his head. “It’s too dangerous. The next boat could also capsize.”

“If you send me back, those men who took Wahid might come for me.”

“We have to take that risk.”

“We will take the other risk. The risk of surviving the boat.”

“If something goes wrong, what will I tell your father?”

Nabeel looked him squarely in the face.

Nabeel looked him squarely in the face. “If something goes wrong, neither you nor I will have to face Bowa. In case the boat capsizes, we both will swim.”

Picture design by Anumita Roy

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By