Reading Time: 10 minutes

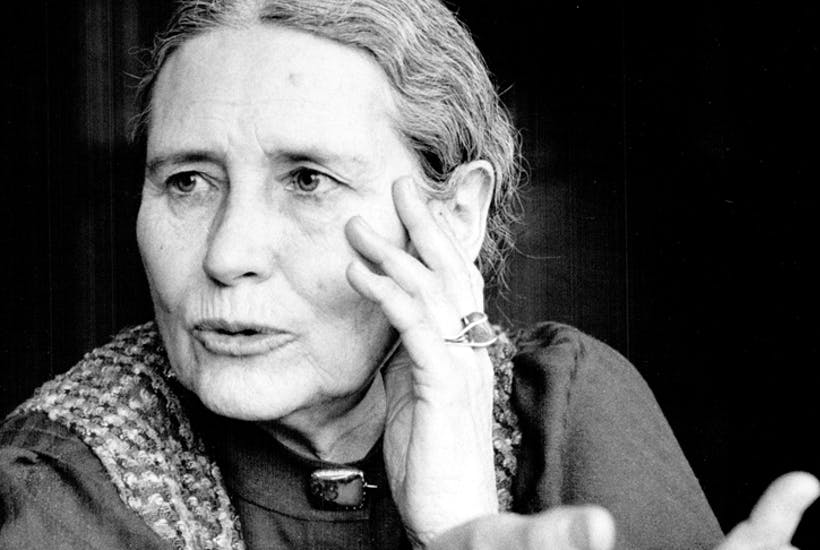

Doris Lessing was born to British parents, Alfred Taylor and Maud Me Veigh, in 1919. After the First World War, her father migrated to Africa and purchased three thousand acres of land to do farming. Her parents, her isolated and lonely childhood influenced not only the themes in her fiction but also shaped her as a fiction writer. Her position as one of the major women writers of the twentieth century is now assured, stands quite apart from the feminine tradition of sensibility. Her fiction is tough, rational, concerned with social roles, collective action and conscience, and she is unconcerned with the niceties of style and subtlety of feeling for its own sake, states Dr. Madhuri, in her research paper. A Different Truths exclusive for the Special Issue on Africa.

Doris Lessing spent her childhood and the first twenty five years of her life in Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and her experiences there have been a powerful influence on her fiction. She was born to British parents, Alfred Taylor and Maud Me Veigh, in 1919. After the First World War, her father migrated to Africa and purchased three thousand acres of land to do farming. Her Parents, her isolated and lonely childhood influenced not only the themes in her fiction but also shaped her as a fiction writer.

Doris Lessing, whose position as one of the major women writers of the twentieth century is now assured, stands quite apart from the feminine tradition of sensibility. Her fiction is tough, rational, concerned with social roles, collective action and conscience, and she is unconcerned with the niceties of style and subtlety of feeling for its own sake. The prevalence of colonialism in Africa is important to her, moulding her outlook towards people. ‘African identify’ is seen by her as the product of Europe’s gaze and returning its own anti-colonialist look. For Lessing, there are two Africas – the continent which always belongs to the Africans, and the label or veneer which the White colonial has imposed upon it. The notion of Africa also emerges as the homeland of dispersed population in search of solidarity and the construing of black identity as creolized and dislocated. The term “Black” at times deployed as a multi accented signifier of oppression and resistance has energized a discursive stance. As Benita Parry puts it ‘Negritude is not a recovery of pre-existent state, but textually invented history, an identity affected through figurative operations and a topological construction of blackness as a sign of the colonized condition and its refusal’ (45). Such multi-valences prompt both closure and fixity, making it available to other modes of oppression.

In Doris Lessing’s writing there is a detachment, marginality as she belongs to neither of these two worlds. There is no significant connection between the White and the Black worlds because of the restraints on a socially formed and positioned author, and the ‘objective narration’ of African culture is related to the writer’s refusal to violate its rhythms, meanings and mysteries. It seems that the composite image of Doris Lessing is very different from the self-image which she presents in her autobiographical novels, even though the facts themselves often concur. The composite portrait has its own reality. The experience of the White Rhodesian, who came to settle in a culture foreign to his British tradition, raised and educated his family in the wilderness, created a productive agriculture for this land and saw the British motherland turn against her own progeny in the political economic feud over Rhodesian racial policy. Lessing herself became a prohibited immigrant to Rhodesia, after 1956. Thus, there is a strong dichotomy and ambiguity in her African short stories and in her non-fictional world. The different voices are not all written as ‘heard’ by their White ‘interlocutors’ and the multiple differences are also not erased by a generic otherness. As Lessing writes in Going Home, “Africa belongs to the Africans, the sooner they take it back the better. But a country also belongs to those who feel at home in it (16)’’. Being a colonial means essentially that one is living in a strange land and this applies even when the family has lived for generations in a foreign country. The “home” is thus alien and growing up here means deep cultural difference of being one and yet an outsider in the country they have adopted. In order to maintain their separateness and their identity the whites generally carried their own cultural distinctiveness imposing it where it could be imposed and distancing themselves where it could not be.

The source of all her ‘African’ stories is found in her own experiences as a girl in southern Rhodesia. Somewhat solitary and in a manner tending towards what would in such a society be regarded as ‘tomboyish’, she grew up bound by her father’s farm and her mother’s house. The recurring feature in Lessing’s fiction dealing with this period in her life is that of a young girl hovering between these two self-contained but related worlds. In the story, The Flavours of Exile, the English family share the language of nostalgia and despite rich and luxuriant vegetables, always long for their inheritance of Brussels sprouts, cherries, English gooseberries, while the children enjoy the ‘inheritance of veld and sun’ (50). The story subtly captures the pangs of love and desire in the heart of the adolescent narrator towards William Mc Gregor, the neighbour’s son. These youngsters do not have the option of breaking out of the social and educational ‘traps’ set for them, they can only religiously build their adolescent dreams. The golden pomegranate in the narrator’s courtyard epitomizes her love and infatuation for William which ripens and grows and suddenly her whole life becomes concentrated in the ripening of that single fruit. But when the boy Mc-Gregor visits the family, he casually snaps the fruit with a stick and shatters her illusion “it was bad, after all the ants had got it. It should have been picked before” (56). This brings her to a new realization and awakening. She accepts the verdict and her position as an outsider in his life. Adolescence can be assessed in terms of the unique orientation to the natural and interpersonal world it represents. The encounter between the self and the world is the first essential crisis and encounter with experience and outside world, which gives the person knowledge, recognition, also shock and conformity.

Another story, Traitors, captures the excitement of growing childhood years, where the children discover the Thompson’s house in the wilderness. The story rightly captures the beauty of the bush, the growing up fears, the excitement, the guilt and their innocence.

We were stopped again where the ground dropped suddenly to the veil, a twenty foot shelf flattened grass where the cattle, went to water, sitting we lifted out dress and coasted downhill on the slippery swathes, landing down with torn knickers and scratched knees in a donga of red dust, scattered with dried con parts and bits of glistening quartz. The guinea fowls stood in the file and watched us, their heads lifted with apprehension [84].

Doris Lessing captures the beauty of her house, a thatch of wild grasses, the uneven walls, the leaking roof in Going Home, even after it was overrun with ant heaps and mingled into the bush, it was home in Lessing’s imagination. The Lessings lived in real poverty in a pole and dagga (mud) house. She described this house in her book, Going Home, as ‘like a living thing responsive to every mood of the weather and during the time I was growing up it had already begun to sink back into the forms of the bush. I remember it as a rather old, shaggy animal standing still among the trees lifting its head out over the viel and valleys to the mountains’ (41). The primitive nature of the house, the talk of the adults, the sense of space and isolation, all these were potent factors in Lessing’s growing up years.

The stories also capture the colonial society In the story ‘The Black Madonna’, Lessing is ‘full of bile’ for the white society in Rhodesia as she ‘knew and hated’ it (African Stories] The story constructs a two-fold process of displacement and ends with an ironic twist where by the native refuses to yield to the White coloniser’s demand for supremacy. Michelle, the artist, paints a Black peasant Madonna, in Zambezi, which is a tough, sunburnt, virile, positive country, contemptuous of subtleties and sensibility. Zambezi, as she puts it mildly, ‘unsympathetic to those ideas so long taken for granted in other parts of the world, to do with liberty, fraternity and the rest’ (93). The ‘culture loving ladies’ of the society only offer sentimentality and gushing patronage to the artist, their notion of culture and art extending to little superficial knowledge. The Black Country is in fact an occupied German village and when it is shelled, the church, the hospital building and everything collapses but the picture is saved by Michelle for the captain. The author, like Sartre, applauds the act whereby the oppressor seizes a word hurled as an insult and turns it into a means of vindication. The captain’s realization is the story’s conclusion as in saving the picture, he shields and protects the captain’s world represented by Nadya and his black child. Doris Lessing grew up to be a writer in such a society and had to find a way of dealing with these polarities. By 1930 and 1940, the maintenance of the White superiority was becoming increasingly difficult to justify in economic and political terms. Poor Whites and educated Blacks muddled the simplicity of earlier categorisation and redefined the composition of the ‘proletariat’.

The strength of Lessing’s fiction comes from her comprehension both of the prevailing myths and of the forces, which challenged them. She explores many of the cultural myths in the white dominated society of Rhodesia in her short stories. Pigis another story, which explores the sexual dichotomy in a straight, broad, direct and much less beguiling manner. It begins with a generalized description in which a character is etched against a landscape. ‘The farmer paid his laborers on a Saturday evening when the sun sent down By the time he had finished it was always quite dark and. from the kitchen door where the lantern hung, bars of yellow light lay down the steps, across the path, and lit up the trees and faces under them.[79]

Dialogue is introduced when the mutual distrust between the employer and employee has been carefully delineated and then the story bifurcates. The farmer, wanting to put a stop to the theft of his meal cobs, refers to culprits as pigs knowing well that pigs are his own farm hands. Jonas, the native gunman is assigned the job to shoot the pigs as they destroy acres of cultivation. Instead, he tracks down and discovers in person the young man who visits his wife at night and had been ‘thieving his wife’. ‘A pig’ said Jonas aloud to the listening moon, as he kicked the side gently with his foot ‘nothing but a pig’. He wanted to hear how it would sound when he said it again, telling how he had shot blind into the grunting invisible herd’. (81) The story concerns itself with the masculine theme of the exercise of power and its frustration. With indirectness and irony, the author through the structure of the story provides implicit moral comment on the relationship of a man with another man when the division of colour, race, and sex obtrude and shows the writer already beginning to realise that the most telling way of making her point is through indirection and irony. It is not an idealised monolithic, homogenised Africa, which valorises indigenous culture; the plot and characterization are sufficiently powerful to convey the message. Each story is a process of growing up, of explaining the conflict between White sensibility and African culture. The fact that each displacement and alienation of the characters ends with forced compromise creates an awareness of the impossibility of setting in this African ethos.

A child perception about the surrounding is another device used by the author in the story providing her with an openness and honesty to explore the land and the circumstances the child’s life clearly mirrors the ambiguities of rejection and affirmation, revolt and conformity, hope and disenchantment observed in the culture at large. “This was the old chief’s country” has a fourteen year old narrator who, despite her African nurturing, feels greater proximity with the English tradition and landscape. The oak and the ash trees are more close to her than the African bush and shrubs. She befriends an old tribal chief in the bush and her attitude towards the native changes’ It seemed it was only necessary to let free that respect that I felt when I was talking with old chief Mshlanga to let both black and white people meet gently with tolerance for each other’s differences, it seemed quite easy’ (Collected African Stories, 17}’.The chief’s son works as cook at her farmland and she undertakes a journey to his house through this unfamiliar bush, experiencing new terror. The formal welcome by the chief further leaves her nonplussed. She returns feeling excluded ‘there was now a queer hostility in the landscape, a cold sullen indomitability that walked with me, as strong as a wall, as intangible as smoke, it seemed to say to me; you walk here as destroyer’ (22). This belief is further emphasised when her father usurps the goats of the natives who have his crops. The loss is a big one for the chief, especially when they face a dry season ahead. As an indirect result of this alteration the villagers are moved from their kraal to a distance reserve emphasising the White/colonial takeover of the Black native land. The girl’s final realisation is that no easy apologies will make her any less a usurper; neither will Africa or bush ever belong to her. Her confrontation with the old man of grace, dignity and reserve provide a moving contrast to values of her mother and her father. It also initiates a revaluation of the white ethics and confounds the sexual polarities inherent in it ‘I had learnt that if one call a country to heel like a dog, neither one can dismiss the past with a smile in an easy gush of feeling saying I could not help it. I am also victim (24).

The next story perhaps captures part of their boyhood years – Doris and brother, Harry Taylor, spent most of their time hunting in the bush searching for duck, wild pig, antelope, guinea pig or whatever around. Her autobiographical essay, Myself as a Sportsman, also reflects her childhood skills. The story, A Sunrise on the Veld, peeps into the psyche of a fifteen-year-old boy, who starts on his morning expedition, feeling strong and invincible, “There is nothing I can’t become, nothing I can’t do, there is no country in the world I cannot make part of myself if I choose” (28). He is appalled to discover a dying buck, eaten by a swarm of ant, a part of the “vast, unalterable cruel veld’’. The buck had fallen a prey to ants as native hunters had broken his leg. The story ends with the boy’s moral realisation of his action who himself had often shot animals, without bothering for the consequences. The author in one shift explains the impersonal forces of the veld shifting from the boy’s feeling of triumph to impersonal stoicism to his own role and place in this suffering. Doris Lessing works on her colonial experience in these African stories. She speaks of her own life, her own early perception of the prevailing racist values. She also portrays the class bound life of English settlers and her ‘colonial bile’ becomes bitterer when directed towards metropolitan culture. Some of the stories are also a reaction to Gambesons insensitivity. She also tries to retrieve the value and dignity of a past insulted by European representation. Her integrated self is in vital interaction with an authentic culture community. She looks beyond the English myths of White superiority and the Black and White detachment. She comprehends her work as a quest into the hidden places of the unconscious. Her total work fits into the quest pattern and the mythical cycle described by Northrop Frye. Lessing’s central character are poised upon a dialectic of openness and cynicism, between “the integrity of the innocent world and the assault of experience.’’ (The Anatomy of Criticism, 87). They pass through two phases in their quest- an early initiation into adulthood and later a renewal of energy before some cosmic disorder in which society breaks up into small units or individuals. Gradually, Lessing grew out of this wilderness and moves on beyond this continent to gather in more experiences and knowledge both theoretically and technically.

References

Frye, Northrop: The Anatomy of Criticism, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1957.

Lessing, Doris: The Sun between Their Feet: Collected African Stories .Vol 2, Flamingo, Harper Collins, 1953.

– Going Home, New York, Panther, 1968.

– African Stories 1964, New York: Popular Library, 1965

– This was the Old Chief’s Country; Collected African Stories. Vol 1, Popular Library, 1973

Parry, Benita. Post-Colonial Studies: A Materialist Critique, Routledge, London, 2004

Photos from the Internet

#Africa #SpecialFeature #DorisLessing #AfricanStories #DifferentTruths

It’s so beautifully written Madam that one should read this article (who wants to know about Doris Lessing )instead of wiki. Not just information ,facts and data but the article delves deep into the life of Doris Lessing.

Regards