Abhignya analyses Tolstoy’s “The Death of Ivan Ilyich,” exploring themes of mortality, authenticity, and the search for meaning in life and death, exclusively for Different Truths.

Writing that mulls over death is often difficult to consume. Nevertheless, the act of reading texts that unsettle or disturb can provide insights about oneself, behaviour, and the human condition. Over the ages, many an account of death has been evocatively crafted. In Wuthering Heights Emily Bronte writes of Heathcliff’s misery as he hysterically addresses Catherine in death. He beseeches her to haunt him, to return as a ghost- anything would be better than to bear the loneliness of being left behind.

Feminist critic Simone De Beauvoir’s essay on her mother’s passing An Easy Death is another reflection on life in the wake of loss. She discusses hospital visits, the demands of old age, and grieving for someone loved and tolerated. Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Nobel winner and master of magic realism, writes in his book Love in the Time of Cholera that “the people one loves should take all their things with them when they die” meaning, memory is embodied in the knick-knacks of ordinary life. What does one make of the various objects that retain the person’s essence long gone?

Journalist and fiction writer Amitava Kumar describes the unnerving feeling of returning home for his mother’s funeral in Pyre. He sketches for the reader a shockingly honest picture – as relatives flood the house, men have their heads shaved, and women wail and bathe the ‘body’, it is the strangely jarring presence of a bar of Pears soap that catches the author’s attention; his mother had used it.

Life and Meaning

Siddharth Dhanwant Sanghvi in his text Loss (that has to do with the memory of his diseased parents and once beloved dog) explores life and meaning in the context of bereavement. He claims that perhaps death means “freedom from language” i.e., where silence and peace prevail; there is no need for translation from thought to speech. Stoic thinker Marcus Aurelius in Meditations consoles the believer: “If there be any Gods, is it such a grievous thing to leave the company of men?”

Nothing quite prepares one for the occasion of death (one’s own soon or that of a family member), though literature can at least help trudge through life. Amongst the most profound stories that serve as guideposts to seek meaning in life (and death), are the ones penned by the Russian masters. The cold landscape of the politically disrupted lands of Siberia, Ukraine, Belarus etc produces the most harrowing tales of loss.

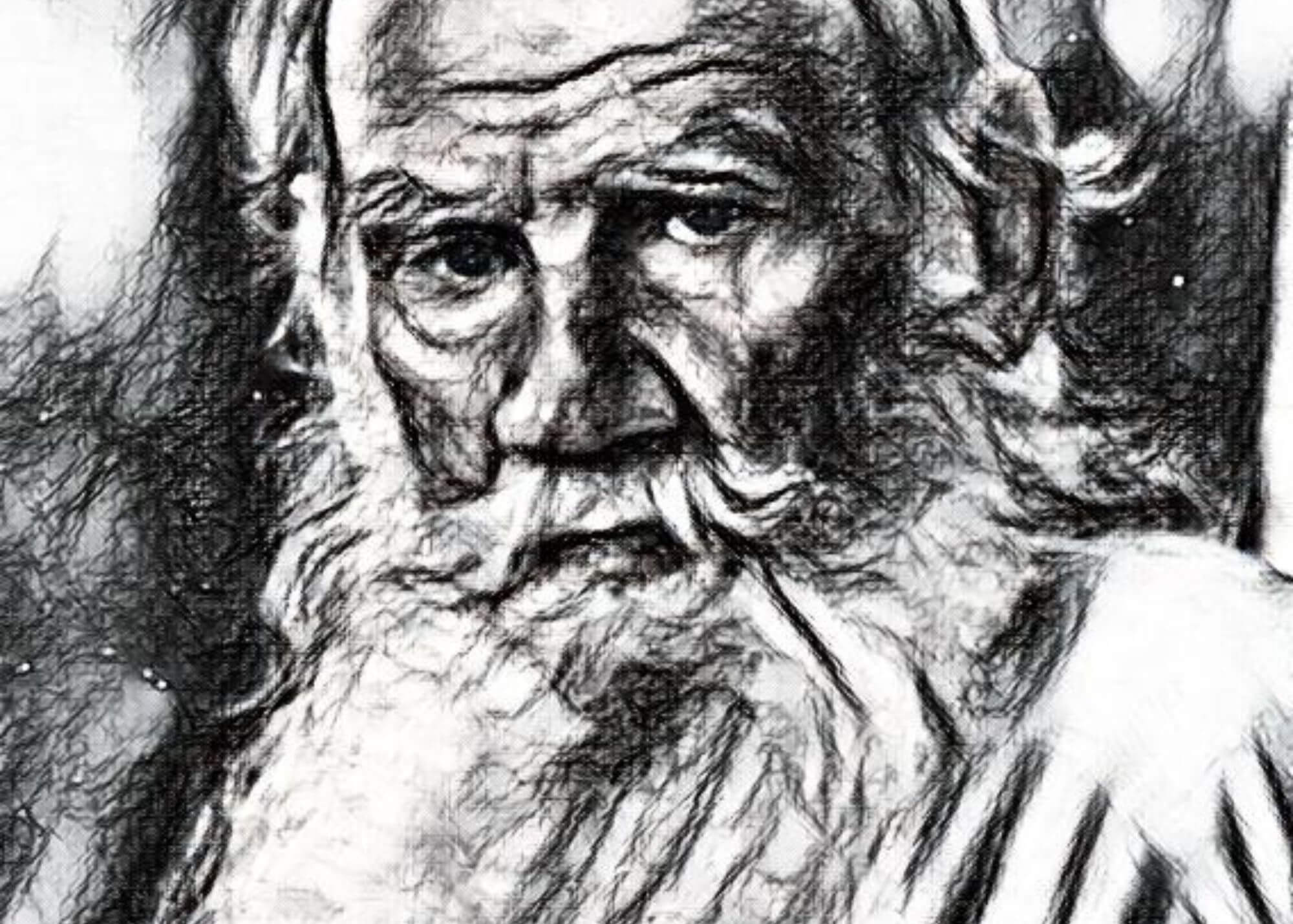

This article attempts to provide a lens through which to (re)approach a serious, canonical short story, The Death of Ivan Ilyich, written by Leo Tolstoy; Ivan Ilyich’s story encourages the reader to be honest to her person in an age that demands only conformism and mimicry.

Tolstoy: A Complex Personality

Tolstoy (1828-1910) is known for the hefty, dense novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina. He was a socialist, a pacifist, a moralist, and a complex (eccentric) personality. He spoke thirteen languages, served the national army, had several children, stitched his shoes, survived a bear attack more than once, and died in a dingy cabin at the railway station as he left home for good after the ripe old age of eighty. In his novella, Family Happiness, the writer defined the model life. He wrote (for a character):

“I have lived through much, and now I think I have found what is needed for happiness. A quiet secluded life in the country, with the possibility of being useful to people to whom it is easy to do good, and who are not accustomed to have it done to them; then work which one hopes may be of some use; then rest, nature, books, music, love for one’s neighbour – such is my idea of happiness. And then, on top of all that… a mate, and children, perhaps – what more can the heart of a man desire?”

When The Death of Ivan Ilyich was published, Tolstoy was an established thinker at the end of his years; all that he learnt and believed about life became the essence of the story. The plot of the tale is as follows: Ivan Ilyich is a high court judge of an enviable standing in society who dies at the age of forty-five. He is diagnosed with a fatal illness and reflects upon the choices of his past for three long months before he finally succumbs to the reality of his end. The question that is posed in the text is an important one: What makes a good death? A good life might make a good death but what constitutes a good life? (I think we can die well if we have loved well).

As the news of his passing is announced in the court, his old colleagues first think of the official position that is now left vacant. Who benefits and how? Aloud they claim the death was a pity and how they feel sorry for their friend. Dishonesty colours the conduct of those who hear of the loss. They remain unsure of their feelings. Tolstoy’s omniscient narrator remarks then:

“…the very fact of the death of a close acquaintance aroused in everyone who heard of it, as it always does, a feeling of pleasure at the thought: it’s he who has died, and not I”

As they visit the widow before the final service, they think of a game of cards that is to happen that night and how long it might be before they may leave. Praskovia Federovna, the said widow, thinks of the pension she needs to sustain herself and the troubles that lie ahead (the immediate one being arranging 200 roubles for the grave), her grief, she says, does not affect her ability to care for practical affairs. It is unfortunate that when a loved one passes away, it is the most affected who have no time to grieve, for they need to take care of logistical formalities. These never end and the initially repressed emotions never fully surface.

Ivan Ilyich’s Life History

The next section of the story deals with the story of Ivan Ilyich’s life history. A quiet middle child, he grows up without a passionate drive but wishes to make something of himself. He works diligently to secure a reputed job. He marries not having fallen in love. He achieves the goals society has set for him but one does not know if he is happy or leading an authentic existence. Tolstoy describes the “…the correctness, rightness, and propriety of his life” in a wry tone. His wife remains sullen most of the time, demanding a better life in society. Ivan Ilyich, now a father and middle-aged, gathers the money to buy a property that suits their image. Yet, they aren’t elated. Tolstoy writes:

“So, they began living in their new home, where—as always happens when one is properly settled in—there was just one room too few; and living on their new income, which—as always—was just a little bit too small, a matter of some five hundred roubles…. And everything went on just the same, and everything was very good”

Ivan Ilyich takes it upon himself to decorate the new house. On one occasion, as he attaches a curtain, he falls off a ladder and has been bedridden since. It becomes common knowledge that his fate is sealed as his state is critical and fragile. He is trapped on his couch and remains irate all day. As a previously well-travelled, working professional he feels utterly helpless as he whiles away time staring at the wall of his bedroom. The vitality and health that he notices in others offends him. They gleefully attend musicals as he feverishly dreams of the past. How dare they continue to celebrate life when he lies in the limbo, half-dead already? No one can understand the delicate mental state he nurses. He begins to re-visit the events of his boyhood and reflects on the notion of mortality. Never once did he consider the possibility that his life might end:

“That syllogism he had learned in Kiesewetter’s Logic: ‘Caius is a man; men are mortal; therefore, Caius is mortal,’ had seemed to him, all his life, to be correct only for Caius, but not at all for himself”

He notices a grim change within his constitution; he is enraged. In a movingly tender scene, Ivan Ilyich watches himself in the mirror as he holds onto a photo from his past. How different he felt were the two men! He perhaps realises he has been living in what Sartre calls “bad faith”, an inauthentic existence that does not align with one’s values and desires but only follows the well-trodden path. Ivan Ilyich has ticked all the right boxes, but he is not satiated with life; it seems as if his presence or absence makes no honest difference in the lives of those who know him. He finds solace only in the company of a serf who helps him clean and rest.

The Idea of Death

The young serf, Gerasim, turns out to be the one person who treats the idea of death as the norm. Tolstoy writes of Gerasim’s dedicated service to Ivan Ilyich as follows:

“…he did not mind the trouble he took, because he was doing it for a dying man, and hoped that when his time came someone would do the same for him.”

Gerasim recognises and acknowledges the existential truth that the grave is the final resting place for everyone; one ought to treat the notion of dying as a rite in life and not as an alien sensation coming from the beyond. He makes the effacing figure of Ivan Ilyich feel respected and loved in his (fast-decaying) skin. The reader is expected to learn from Gerasim to be stoic and from Ivan Ilyich, to live so as not to regret when her time comes. Sartre, in his play No Exit, talks of the moment of death, sudden, absurd, and uncompromising:

“One always dies too soon – or too late. And yet one’s whole life is complete at that moment, with a line drawn neatly under it, ready for the summing up. You are – your life, and nothing else.”

When the line is drawn under Ivan Ilyich’s life, it is an unsettling occasion. He has screamed for three days in pain before. When he realises that he is about to die, he begins to see a light that he longs to reach. It does not seem half-bad. Nevertheless, he continues to scream for the physical agony he is put through is unbearable. From the outside, it appears as if he is greatly tormented and requires respite but Ivan Ilyich, after a life that is ridden with strife, is only about to experience happiness and silence for the first time. He is comforted by the hope of sweet release.

The reader has access to both perspectives and is to now make his/her call – which experience rings (more) true? Ivan Ilyich’s story is important (especially in the present when social media takes away from experiential reality) for many reasons. In times characterised by fleeting moments of calmness in between the many appearances one cultivates to fit in, Gerasim’s quiet resistance (in the face of inauthenticity and disbelief) becomes necessary to emulate.

Tolstoy’s Universal Ideas

It becomes important to pay attention to one’s inner life and calling when carefully curated online personas appear as aspirational ideals. Tolstoy writes of universal ideas and over a hundred years later his lessons are of use still. These pertain to the universality of death, the value of health, the impact of kindness, and how freedom is to be equipped in life.

Tolstoy urges the reader to live life only on her terms, to choose love, to work for passion, and to (eventually) die in grace. The Death of Ivan Ilyich, therefore, is a parable one needs to (re)read today.

Picture design by Anumita Roy

By

By

By

By

By

By

Wish to live half as adventurous life as Tolstoy, would try to avoid losses though!

Didn’t expect to read about a morbid topic with such ease haha

Thank you Abhignya <3