Sohini and Rishi discuss Dhumavati’s shadow, highlighting Dhumavati’s suffering (contrast with Bhairavi’s genius), and Bagalamukhi’s light of consciousness, representing inner control, exclusively for Different Truths.

Bhairavi personifies unbridled genius, whereas Dhumavati represents the shadow side of existence. Our personal experiences have taught us that life can be exciting, joyous, and pleasant emotions we want to embrace and experience to the maximum. But other times, we discover that this same life can be gloomy, sad, uncomfortable, and stressful. We typically react to such circumstances with pessimism, grief, anxiety, or rage. At that point, we desire to escape life’s suffering rather than to embrace it.

Herein lies Dhumavati’s role. Smoke is one of the consequences of fire, and her name means “she who is made of smoke.” It is symbolic of the most negative aspects of human existence because it is dark, polluting, and hidden. The ideas that Dhumavati embodies are very old, and they have to do with preventing life’s unavoidable sorrow. Three former goddesses served as the models for the Mahavidya Dhumavati before she ever existed. They are related to one another closely and share a lot of traits. Dhumavati likewise possesses many of these traits, yet there is also a significant difference between her and them.

The goddess Nirriti from the Rigveda is Dhumavati’s earliest inspiration. The first seers imagined rita, a universal moral law and principle of cosmic order. Dharma is the name given to the moral component of rita. A negative of the name Rita is Nirriti. Nirriti is the opposite of rita, which stands for order, growth, wealth, prosperity, harmony, well-being, and the goodness of life. She personifies all of life’s evils, which include disorder, decay, poverty, misfortune, discord, illness, and death. In contrast to other Vedic goddesses, Nirriti was ritually appeased to fend her off rather than being worshipped in the same way. The refrain of the Rigvedic hymn that refers to her (10.59) is, “Let Nirriti depart to distant places.” The intention was to keep her far away.

Jyeshtha, whose name means “the elder,” is a close relative of Nirriti and symbolises the deterioration that occurs with ageing; she is, of course, portrayed as an elderly woman. On an instinctual level, she is compelled by conflicted homes—those where relatives fight or where parents fill their bellies while their kids go hungry. She was probably propitiated, much like Nirriti, to keep her at a safe distance.

Alakshmi is one of Jyeshtha’s monikers, which denotes that she is everything that Lakshmi is not. She resembles Lakshmi in the dark. According to the Candi, Alakshmi is the one who brings bad fate to the households of the unrighteous. She represents all the dreadful things that can happen to people, including poverty, misfortune, and poor luck.

These three titles all relate to an unlucky goddess who is depicted as having a dark complexion, which denotes her tamasic temperament. She is undoubtedly the model for the Mahavidya Dhumavati due to the obvious similarities in both character and iconography.

A characteristic is the frequent reference to a crow. Sometimes the crow is imprinted on Dhumavati’s banner, and other times it is perched above the banner. Sometimes the bird is shown as enormous and acts as her mount (vahana). She may be accompanied by a group of crows in certain depictions. In any event, the crow, a carrion eater, represents death. For a goddess of disaster, decay, devastation, and loss, it is a suitable consort.

Like her models, Dhumavati is associated with negativity, need, hunger, thirst, and quarrelsomeness. She is always shown as being elderly, unattractive, and having sagging breasts and broken or missing teeth. She is wearing soiled rags. Here, we can deduce two things. One is that our distaste for life’s terrible events will eventually cause us to gravitate towards the Divine. The second is that everything, including what we typically view as repulsive or unsightly, is marked by the Divine. How could there exist a location devoid of the infinite Mother?

Dhumavati is distinguished from her predecessors by being described as a widow, which gives a hint to her special nature as a Mahavidya and sets her apart from the earlier goddesses, who are to be avoided. The distinction is that Dhumavati has several advantageous features.

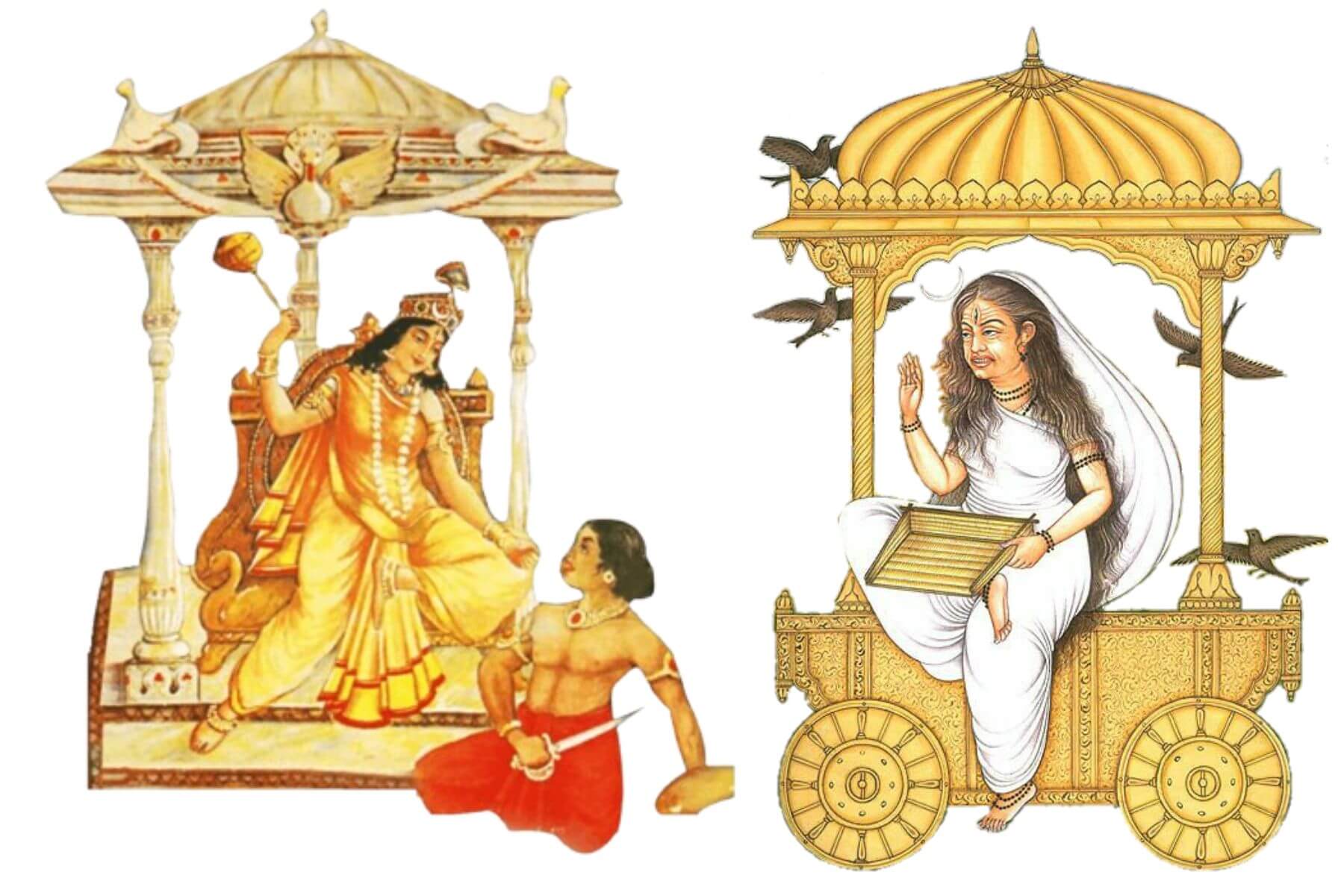

In Indian society, widowhood brings a variety of complications. Traditionally, being a widow is an undesirable situation. A widow has lost her former social status without her husband and could start to be seen as a financial drain on the larger family. This is shown by the empty cart that Dhumavati is sitting in. On occasion, a drawing depicts two birds being tethered to a wagon, but instead of being empowered, they look like they are battling something too massive and heavy for them to pull.

The social marginalisation of widows within the context of traditional Indian society may also be a sign that their worldly worries have passed. Widows now have the freedom to pursue a spiritual path, travel on pilgrimages, and practise sadhana—activities that would have been difficult during the years spent fulfilling household responsibilities. They are free to fully devote themselves to spiritual practice since they are no longer restricted by the requirements of the marital condition. The forced state of widowhood and the voluntary state of renunciation known as samnyasa are implied to be paralleled in this passage.

Is there anything we can learn about traditional Hindu society that is more general and applicable to our experience than the unique conditions and rituals that are observed there? Dhumavati should be able to offer some useful advice because the Mahavidyas are all believed to be wisdom goddesses who want to guide humans towards enlightenment.

The main lesson is that fortune may appear differently in hindsight. Everyone agrees that sometimes things that looked painful or bad at the time turned out to be for the best, or in other words, a blessing in disguise. For the most part, the examples of disappointments, calamities, frustrations, defeats, or losses that resulted in positive transformation may be found in our own lives or the lives of people we know. How success can shape character, failure can elevate an average spirit to remarkable.

Another lesson is that as time passes, we eventually experience losses of some kind and must learn to accept them. Dhumavati is a metaphor for the corrosive power of time, which robs us of our loved ones, our youthful vitality, our health, and everything else that adds to our frail happiness. Everything we so fervently hold onto for stability is fleeting by nature. We must eventually acknowledge our mortality. That is the core issue with human existence.

We know what to do because of the image of Dhumavati, who is depicted in her cart of disempowerment as old, ugly, lonely, and wretched. The key takeaway is to develop a sense of separation. Dhumavati is seen holding a winnowing basket in her left hand and a fire bowl in her right. The flames represent the universal catastrophe that is destined to occur. The winnowing basket, which is used to separate grain from chaff, stands for viveka, the mental ability to distinguish between the lasting and transient. Dhumavati encourages us internally to aspire for the highest, and once we are committed, there is nothing that can stop us, even though her blocked wagon symbolises an exterior life that is going nowhere. She concludes by pointing in the direction of emancipation.

Bagalamukhi: The Light of Consciousness

Bagalamukhi is the Mahavidya whose meaning is the most obscure of all of them. Her symbolism is extremely inconsistent in its interpretation. Even when an informant makes genuinely sound arguments, their beliefs frequently have nothing in common with one another and can seem random and disjointed. Even the meaning of the name Bagalamukhi is not clear. The Sanskrit dictionary does not contain the term “bagala,” and attempts to connect it to the noun baka (“crane”) are not particularly persuasive.

Her dhyana mantras also emphasise the yellow colour of her skin, attire, jewellery, and garland. One of her common epithets is Pitambaradevi, “the goddess dressed in yellow.” When worshipping her, her followers are required to wear yellow and to use a mala with beads made of turmeric. She has yellow paint on even her sparse temples. Although she continuously emphasises the colour yellow in her spoken descriptions, she uses the colour rather sparingly in her visual renderings. Bagalamukhi is typically seen with red or orange clothing. On what yellow is supposed to symbolise, there is also no agreement. The idea that yellow, the colour of the sun, signifies the light of consciousness is the most logical explanation out of a few others.

The other symbols of Bagalamukhi provoke similarly hazy and wildly varying meanings, leaving no clear understanding of what this Mahavidya is about. This circumstance necessitates original thought. The explanation that follows is largely original; however, it is based on a series of hints that were discovered in her mantra.

Consistently, Siddhis, which are yogic powers with magical attributes, are linked to the Bagalamukhi. Such abilities are hurdles that a sincere spiritual seeker should shun. Stambhana, the ability to immobilise, paralyse, and detain an adversary, is one such power. To grasp Bagalamukhi properly, one must have a thorough understanding of what stambhana implies spiritually.

The first thing to remember is that all schools of Indian philosophy believe that there are three layers to the world we experience: the gross or physical, the subtle or mental, and the causal or potential.

There is a story from the life of Holy Mother, Sri Sarada Devi, that takes place around the year 1889 in the Kamarpukur hamlet, and it illustrates the principle of stambhana at the most fundamental level. After making numerous frequent trips to Sri Ramakrishna in Dakshineswar and, after his mahasamadhi, to the monks at the Baranagore monastery, a devotee by the name of Harish left for home. During that period, Harish had ignored his wife and family due to his occasionally erratic behaviour. His wife used drugs and spells to cure the issue, and Harish grew insane. He started pursuing Holy Mother after seeing her one day on the road. There was nobody home when she arrived at the family compound. Harish followed her as she started to round the granary. She ran around it seven times before being unable to go any further. She stayed solid and took on her form as she continued to tell the story. She placed her knee on his chest, got hold of his tongue, and slammed his face so hard that her fingers turned crimson. He struggled for air. At that time, the typically mild Sarada Devi revealed herself as Bagalamukhi and assumed the stambhana posture.

This literal symbolism stands in for a truth that permeates every aspect of our existence and extends to the core of who we are. In this instance, we see Bagalamukhi’s actual presence as a physical representation of the verbal and visual descriptions of her halting an adversary by seizing his tongue and striking him.

The tongue is a representation of speech, or vak, which is a goddess in other cultures. The divine creative power that embraces the full spectrum of consciousness, vak is more than just the spoken word. Bagalamukhi, who is seen gripping her opponent’s tongue, has the power to immobilise consciousness’s creative and destructive potential in all its forms. These include the evident forms of communication at the subtle, gross, and causal levels, including movement, cognition, and intention.

Beyond them, consciousness-in-itself, the ultimate, unconditioned reality, is the highest level of communication. Intention, thought, and motion are the three stages of creation that emanate from it and are responsible for the world we live in. There are passages in the Upanishads Chandogya and Taittiriya that describe how Brahman, who saw itself as One, sought to express itself as the Many, then devised a strategy and finally put it into operation. These three levels are known as icchasakti (the power of will), jnanasakti (the power of knowledge), and kriyasakti (the power of action) in the teachings of tantra. This is how cosmic or universal consciousness functions.

On a personal level, that same consciousness permeates every aspect of who we are and influences everything we think, feel, and do. The ability to speak is likewise part of this interior consciousness, or vak, but as before, the uttered word is merely the result and the crudest manifestation.

Speech can be divided into four levels. Para vak, the supreme, limitless consciousness devoid of attributes or conditioning, is the highest. It is our true Self, our divine nature, and it permeates every aspect of our experience. Pasyanti Vak, which follows, is the stage of vision and the need for self-expression. In a split second, everything in our experience of life starts here. Every emotion we experience, every thought we have, and every action we take all start with an immediate awareness. Ideas start to form in a logical order as we start to think about whatever has just flashed. Madhyama vak, the intermediate, formulative phase, is the name for this state of consciousness. The concepts take on a language-expressed shape as they get more and more concrete. This is the level of articulate speech, or Vaikhari vak. Vaikhari vak is a subtle and disgusting sound. Our thoughts, which have been formed into words, phrases, and sentences but have not yet been spoken, take on a delicate form. The actual sound that emerges from our mouths is the expression of our consciousness in its gross form.

We frequently feel the urge to dominate the other, and sometimes that is legitimate, but not always, as long as we identify with the body and the mind, our experience of self is that of an individual amid the duality of “I and other.” At a higher level, we understand that self-control is a better, but much more difficult, form of discipline. Bagalamukhi represents our natural ability to turn inside and take charge of our awareness. Yoga is the cessation of continual modulation (cittavritti) inside our field of awareness, according to Patanjali. We can only be released from the shackles of the material world and rest in the serenity, joy, and grandeur of our true nature by seizing control of the activity within our awareness and stopping it.

The purest form of stambhana is yoga. We are prepared for asana once we have properly observed the moral standards of yama and the elevating followers of niyama. Sitting still causes the body to stop moving, which slows down our metabolism and helps us focus our minds. The final four states—pratyahara, dharana, dhyana, and samadhi—are a progression of ever-decreasing activity that ends with the realisation of the Self as unadulterated consciousness. Bagalamukhi is dragging us there by the tongue.

(To be continued)

Cowritten by Rishi Dasgupta

Rishi Dasgupta, a Masters in Economics from the University of St. Andrews, Scotland, is a millennial, multilingual, global citizen, currently pursuing a career in the UK. An accomplished guitarist and gamer, his myriad pursuits extend to the study of the ancient philosophies and mythologies of India. ‘Adi Shiva: The Philosophy of Cosmic Unity’ is Rishi’s second book as co-author.

Picture design by Anumita Roy

By

By

By

By