Dr Aaliya reviews Richa Bajaj’s ‘Bitter Orange Poems,’ focusing on the self’s paradoxical role as both observer and participant in life, exclusively for Different Truths.

The overarching question in Bitter Orange Poems (2024) by Richa Bajaj revolves around the self and its truths. The self remains central to perceiving, absorbing, and responding (both emotionally and linguistically) to life. Yet, paradoxically, while positioned at the centre, it often exists merely as a spectator. The self takes on the dual role of both the observer and protagonist, becoming a poetic space for contemplating the tension between witnessing and actively participating in experience. The following lines appear in a poem titled “A Discourse”:

The world in eyeball saturates,

Hands empty as thought, Jittery as feeling.

Informed, aware,

Young faces

Caught in dilemmas of old… (71)

It is much like Saul Bellow’s protagonist in Mr. Sammler’s Planet, who finds himself caught between reconciling with the outside world and seeking a deeper understanding of his own identity. For instance, the expression in the poem “Stained Glass” reads:

Somewhere I want to sketch

The queen of chess

Quietly waiting

For her turn in this mess. (9)

Beyond humour, there are deeply poignant encounters between the self and the subjective “I”, beautifully likened to long-separated lovers finally speaking again in the poem “Gorge”. The contemporary idiom that follows the strange, rather surreal meeting lingers in the mind long after the poem ends. Meanwhile, the functional lists of life (mundane concerns like household bills) intervene an almost mystical coming together of the self holistically, overshadows the shared intimacy- like that of a married couple’s everyday conversation characterised by drudgery:

We haven’t spoken much of late.

Have been evading each other

As lovers, forlorn,

Suddenly find themselves face to face,

A prick in heart, a spark,

We met –

My self and I ...]

There were functional lists

We exchanged,

Deadlines we accepted,

Like a married couple

Discussing house bills. (5)

Nevertheless, a cosmic consciousness permeates the imagery of the subsequent poems, much like in Whitman’s “Song of Myself”, where nature is not merely a reflection of emotional states but an extension of the self. The encounter with nature in these verses goes beyond symbolic projection; it stands as an expansive unison of the self with nature outside of itself. In the poem “Nestling”, the verses transcend the narrow confines of subjectivity, immersing the reader in the breathtakingly intricate symbols of nature. Here, much like Whitman’s poetic self that dissolves into the universe, the speaker experiences a liberation that is both personal and cosmic:

That shiny green moss on rocks,

Mellow to touch,

Is a part of me.

I flowered

In the brown overgrown mushroom,

Close to the chest of the rubber tree.

I kissed the flattered trunks of oak

Nibbled its green nuts

Drew beneath from it

And squeezed me in. (18)

The poetic vastness unfolds as a captivating journey beyond itself, stretching toward the moss-covered rocks, the brown overgrown mushrooms, and the nibbling of green nuts. It embodies the all-encompassing vision of the hawk or the seer, reflecting the poet’s role as an observer of the world. Yet, like the still, placid waters, this journey inevitably returns to the habitable self, one that moves through life, embraces experiences head-on, and ultimately settles into quiet, almost unnoticed contentment. In the poem “Honeycomb Temptations”, the self is like a parachute glider, never fully released, always tethered, yet carrying one through the adventure of forward flight. Even as it soars and navigates the vast expanse, there remains an inevitable return, a continuous coming back to the self while embracing the thrill of exploration:

I walk outside my body for a while

To taste the liquids sweet,

And soon enough return

To the placid waters

Of what I am. (12)

The sweetness found outside may be delightful, yet who doesn’t long to return home, no matter how enticing the adventure has been? In yet another poem, “New Time”, the imagery shifts starkly but conveys the same idea. The poet reflects on the irony of returning home despite its confinements and restrictions. The idea resonates deeply with Kazuo Ishiguro, the 2017 Nobel Laureate in Literature, reflecting in an interview on his novel Never Let Me Go, who said: “I’m fascinated by the extent to which people don’t run away. I think if you look around us, that is the remarkable fact- how much we accept what fate has given us… Sometimes it’s just passivity, sometimes it’s just simply perspective. We don’t have the perspective to think about running away.” One might feel weighed down by anklets, hooves, and bars, yet rather than choosing rebellion, there is always the inevitable pull, one always finds their way back home:

How bars, anklets, hoofs

Are nailed to your feet

Hysterical, they drive you home! (27)

Symbolically, home and self intertwine, converging into one within the poet’s imagination. It is no surprise, then, that in the poem “Doors”, the poet envisions the new woman growing doors, windows, and rooms, allowing her fluid movement between the interior and exterior worlds. The underlying message, of course, is a rejection of restrictive definitions, affirming her freedom to shape her own identity and sensibility:

I wish she [the new woman] had many doors

And many windows,

Many rooms too,

To sneak out of. (31)

The note of defiance resonates even more strongly in the poem “Rough Drafts”. Through rhetorical questioning, the poem challenges reductive, normative, and prescriptive expectations placed on women, confronting them with a sharp, almost mocking tone. The feminist angst is unmistakable, so, too, is the boundless spirit to break free from it: Ends require stitching Packing tight.

Why must I not ride waves fathomless?

Where are ends

And where the beginnings? (10)

Just as silence exists as an intermediate state between contemplation and the spoken or written word, so too do dreams, at times feeling real, surreal, and ultimately unreal. The poems, carefully weaving through the lanes of thought, lead the reader into a deep dive into subjectivity. It is pure artistry as to how, amidst the relentless pace of city life, a poet’s heart cradles dreams, perhaps the weight of vulnerability, unseen by the rush and clamour of the outside world. While the external noise and haste do not penetrate the poet’s dreams, the reverse is also true. In the poem “Dreams”, the contemplative self, moves through the day like a toddler, gathering impressions and returning home with the residue of a poem:

On the road, in metro trains,

Behind conversations,

I fiddle with them

I fondle them

Transported to a life fictive yet true.

All this with the remnants

Of some last nights’ dream. (102)

Likewise, the unease of existence and the blurred transition between dreams and reality, where one eventually struggles to distinguish between the two, finds powerful expression in the poem “On Edge”:

I wait the night out

And wake up to find myself

At the other end of disquiet. (78)

There is a particularly grotesque poem titled “Horror of Horrors”. It carries eerie, nightmarish overtones, with the recurrent motif of a dream, waking up, and an underlying sense of suspicion. Here, one struggles to grasp whether the dread stems from being locked out or something more profound. It is only in the poem’s climactic revelation in the middle of the poem that the reader realizes all its unfolding scenarios serve as a symbolic reflection of life itself:

…still uncertain,

I pull the handle of the door

Only to find

That it’s locked from the other side. (51, 52)

At times, the symbols or metaphors become too dense for the reader to navigate easily. It resists straightforward interpretations and immediate meaning, a defining characteristic of the book as a whole. Even in the few poems that symbolically explore the writing process, one cannot help but be reminded of Ted Hughes’s The Thought Fox. The thought, so to say, takes the form of a fish in the poem “Fish”, while in “No Turning Back”, the imagination manifests as a white horse:

… a picture of a white horse

Eager to jump out of the chipped frame. (7)

Nonetheless, the opaque tone is occasionally interrupted by love poems scattered throughout the collection. There are a handful of exquisitely crafted erotic poems, notably “Bitter Orange” and “A Rose Tree on My Back”. The poem titled “You Speak to Me” introduces fresh imagery, capturing the way love illuminates an otherwise dismaying existence:

Wiping the dry mornings off my face

You speak to me

In colors

On a wildfire day

Filling me with the lemony zest of life. (89)

Just as love offers a respite from tangled thoughts and existential dilemmas, the reader encounters strikingly original nature imagery in the poem “Tree of Life” that reinforces love as a saving grace amid life’s incomprehensibility and its swift, inevitable erasures:

Did you know you are the tree of my life?

In the dense green thickets of misgivings

You anchor my wet soil. (90)

Many love poems, however, subtly weave in elements of some sorrowful, loveless ambience, as

“Autumn and Spring Love Story”, puts together two seasons, autumn and spring, integral parts of the seasonal cycle yet forever apart. The love that blooms in spring inevitably fades by autumn, and the fiery passion of autumn must surrender to the stillness of the season that follows. A deep sense of emptiness permeates the poem, allowing unspoken emotions to find palpable expression. The following verses from the poem unfold an entirely different spectrum, making the poet’s vision of love rather holistic:

Untampered feelings roll over

In letters you never wrote

In envelopes that never went to the post,

Between fingerprints on lips

You found love, sweet autumn,

And yours was never a love story! (124)

The book immerses one in a vast ambit of emotions and experiences, holding the reader in a universal connection that is innate among all selves, each alike, despite their unmatched or unyielding solitude. All the diverse themes draw the reader into becoming a reflection of the poet herself. Upon finishing the book, one doesn’t necessarily feel the need to situate Bitter Orange Poems within a specific context, a misnomer in most cases, but not here. The book itself offers a kind of disclaimer in the poem “Return of Red”:

Even if my red is different from yours

We are all silk-cottons

Blooming in spring. (76)

The poem likens us all symbolically to ‘silk-cottons’, identical in the dividends of life, dreams, desires, fears, love, and the vulnerability of erasure. It is universal within us and expresses the uniquely individual, dissolving the space between ‘I’ and ‘You’, and Bitter Orange Poems serves as its poetic embodiment.

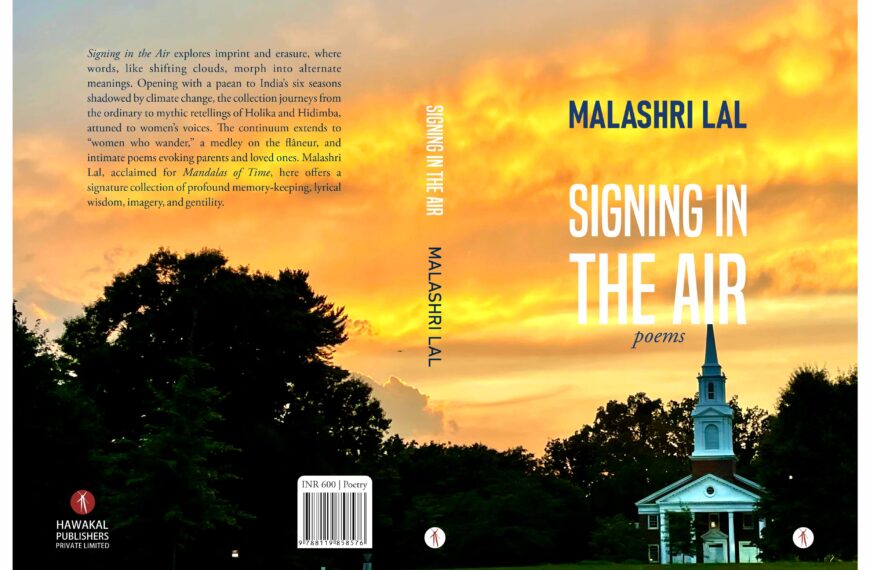

Book Cover from the Internet

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By