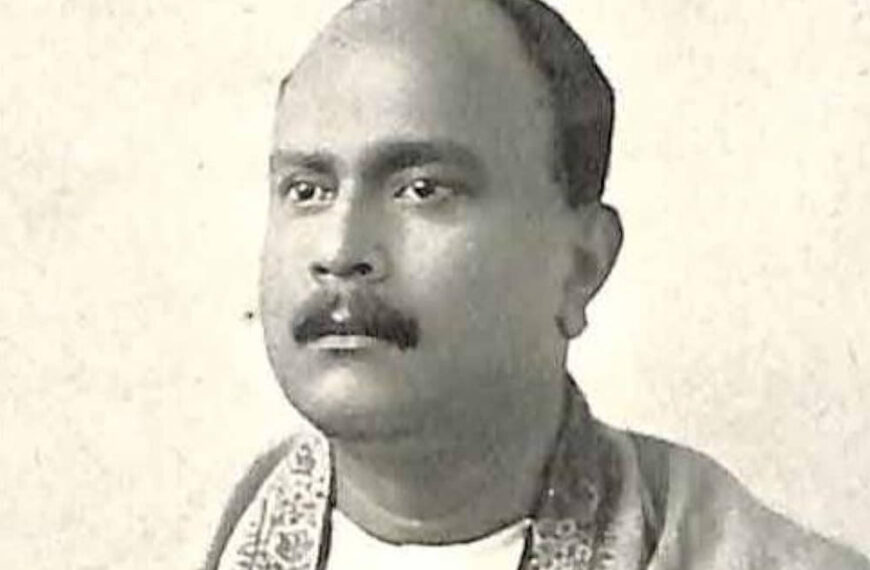

Abhignya’s reflective piece, exclusively for Different Truths, explores the 19th-century Russian writer Dostoevsky’s life, highlighting his profound themes of morality, suffering, and the human condition.

Dostoevsky lived and wrote two hundred years ago. In the Tsarist Russia of the 1820s, as he grew up, he witnessed political upheaval and personal conflict. Dostoevsky’s mother, who was his only honest companion in childhood, passed away too soon. She taught him the scriptures and laid the foundation for his work and thought, even before he knew he was to be a writer. Dostoevsky’s father was abusive and difficult (perhaps that is why the fathers in his stories are erratic, angry, and head dysfunctional families). He was a doctor, and the family lived at the Mariinsky charitable hospital where he worked.

The author witnessed the troubles of poverty (secondhand) and learnt to empathise with the less privileged. When his father (as is conjecture) was murdered by his serfs, Dostoevsky’s world fell apart. He was now a young student training to be an engineer for the army, living in poverty and dealing with the onset of epilepsy. Freud, a famous psychoanalyst and commentator on culture, believed that Dostoevsky suffered from a rare hysteria.

His epileptic attacks stemmed from the guilt he carried for his father’s death, i.e., he’d felt responsible for it because he’d harboured an unconscious desire for patricide all his life. It was his Oedipal complex, latent heterosexuality, and the repressed vengeance towards his father that led to his illness. The use of atropine and other drugs had caused one of his eyes to turn stark black (while the other remained light brown); he became conscious of how he looked and remained underconfident in matters of love.

Hostile to Intellectual Activity

As Russia became hostile to intellectual activity, Dostoevsky and his companions joined the Petrashevsky Circle, a group that advocated dissent and acted against censorship. They discussed socialism and dared to own a printing press to propagate writing the State banned; it was a radical act that led to a notice of execution—death was the only fitting punishment for those who chose to employ agency in the Tsarist climate of the day.

As the political prisoners were chained up to be shot, Dostoevsky thought of the life he could have had (later he’d describe this scene in his novel The Idiot). He prayed for the well-being of his brothers, thanked his mother and Christ in heaven, and noticed the almost unbearable beauty of a beam of light that bounced off a tower in the distance. How grateful he’d felt, nevertheless! Just as they were all to be shot, a messenger from the Tsar brought in a notice that cancelled the death penalty; they were now to serve twelve years in Siberia in hard labour. It was a psychological trick, mock execution, so that thinkers like Dostoevsky would never dare to commit a crime against the State again. The time in jail was harsh, and the writer struggled to make it out alive.

He also understood that Fourier, Chernyshevsky, and other writers who discussed human suffering, utilitarianism, rational egoism, etc did not cater to the common man of Russia. His fellow prisoners helped him realise that lofty ideas of progress and development do not help those who truly need them; they are meant to please the comfortable and satiate their guilty conscience. He thus decided to write for the man of the soil like Tolstoy wrote for the figure of the peasant.

The Love of his Life

Once back in his beloved St. Petersburg, he met the love of his life (in his 40s) and, with her as his stenographer, produced literature that changed the lives of the millions who read him. He wrote as he dealt with the death of his children, lack of resources, flailing health, and periods of gloom. We think of him as a prophet today and read of Svidrigalov, Prince Myshkin, and the brothers of the Karamazov family.

I am a woman in my twenties, living a comfortable life in India, in the (comparatively) progressive timescape of 2024. My PhD, ongoing, is in the philosophy of Existentialism, and thus, I happen to read Dostoevsky for work. But why do I relate to his writing? Why is it that his writing is considered timeless? When Dostoevsky was my age, he was in prison in Siberia, smuggling vodka in the bellies of wild oxen and perpetually on the verge of dying from epilepsy, cold, and draining physical work.

I only have work and relations to manage, and it is not minus thirty degrees outside even on chilly days. When I decided to work on Dostoevsky and the genealogy of Existentialism, I’d only read Camus, Sartre, and Crime and Punishment from Dostoevsky’s otherwise rich oeuvre. Two years later, having supplemented my reading, I understood (through my lens) why Dostoevsky became a stalwart of World Literature.

He continued to write despite the fixities that governed him; trying to make it as a writer even today is akin to bleeding on the typewriter (Hemingway described it as such), and as I try to write (well), I think of the epileptic Dostoevsky in his tattered coat crafting his narratives with patience and zeal. He was starving, but he wanted to write more than he could earn from what he wrote. His stories make me a better person.

Christian Charity

In The Brothers Karamazov, a character passes away and finds herself at the pearly gates of heaven. She has been a sadistic, sinful woman and therefore is refused entry. Her guardian angel fights for her case by reminding St. Peter of a good deed she’d committed once—she’d presented an onion to a hungry beggar, and that act of Christian charity ought to lend her space in heaven. She will be allowed, it is decided, if she holds onto the onion and can fly over the lake of burning souls as her guardian angel makes the journey to heaven.

On the way, the condemned souls from Hell latch onto her and wish to commute along. She acts selfishly and claims that it is her onion and thus no one else deserves the pleasures of heaven. It is at that moment the onion breaks apart, and she falls into the lake of burning souls, condemned for eternity to the torture of hell.

Dostoevsky conveys the idea that one deed of grace and generosity can redeem you, but acts of violence and greed are dangerous. One must act thoughtfully and with kindness. I think of the episode of the onion often. Through the course of Crime and Punishment, Dostoevsky draws for the reader a picture of a murderer, Raskolnikov. He maims and kills two women, one pregnant, and another very old, brutally. He breaks open their skulls with a blunt axe and administers severe blows to their frail, scared bodies. He steals, having refused to believe in God and often mocks his closest associates. Yet, he is the hero of Crime and Punishment, and the reader grows to feel for his state of affairs.

His coffin-like room, destitution, depression, and well-read, good-looking persona elicit readerly empathy. Going through the hefty novel, Raskolnikov establishes himself as a victim of the influence of the West (ideas of utilitarianism, rational egoism, etc.) who only acted in bad faith (but was never a bad person).

Criminal, Not an Outcast

Dostoevsky teaches us that the criminal is not an outcast and dwells over the idea that we are governed by a Jungian collective conscience that is responsible for all. Thus, I am Raskolnikov. Years later, activist and philosopher Foucault would discuss the same concept in Discipline and Punish where alienation caused by the prison system was deemed problematic; justice ought not to marginalize but liberate. Suffering was punishment and atonement. Dostoevsky thus influenced many a thinker. His books are not Nihilistic accounts of suicidal men and women; they teach us how to live well.

Reading Dostoevsky, especially after the mad year of 2020, becomes imperative because his books help answer the universal questions of existence (the answers are, of course, different for everyone). You are a changed person after reading any book but reading Dostoevsky will make you feel grateful for the life you lead and remind you of the beauty of the beam of light Dostoevsky saw as he stood before the firing squad on what was fated to be his last day.

Picture design by Anumita Roy

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

Such a profound article…the language is simple yet engaging…loved it!