Prof Nandini reviews Malashri Lal’s Mandalas of Time, a 75-poem collection exploring themes of feminism, gender equality, mythology, and Indian knowledge systems, with a focus on social transformation—exclusive for Different Truths.

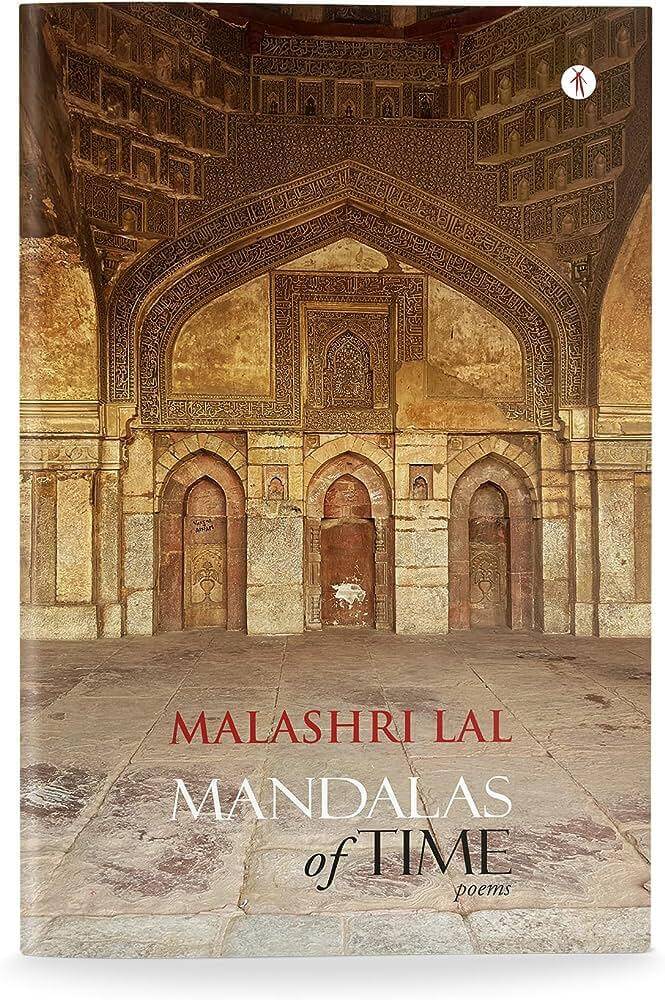

Mandalas of Time by Malashri Lal came to me just yesterday as a pleasant surprise and absolute joy. I read the 75 unputdownable poems in one go, and then read the Introduction by Lal herself, with a worthy Foreword by Bashabi Fraser and a powerful Afterword by Ranjit Hoskote. The production quality of the book is aesthetically appealing with a cover photograph and design by Bitan Chakraborty. I must congratulate the poet and the publishers for this beautiful work.

First, seventeen pages of sheer poetic prose add value to the book. Feminism, gender equality, myth, folklore and Indian knowledge systems are the thrust areas of this collection.

“In this collection of seventy-five poems, we are introduced to the many themes and subjects that fascinate, move and inspire Malashri. Women are evoked or recalled from mythology, (Manthara Dasi), from the Hindu divine pantheon (the two Sita poems which have the appeal of Malashri’s insights) and from history (Hawa Mahal), all given a voice by the poet’s fine feminist sensibility.” (Fraser 8)

She writes mellifluous poetic prose where she pours her heart out in the language of nostalgia.

‘Poetry — The Healing Touch: Dualities, multiplicities’ comes as a breath of fresh air in the form of an Introduction to the book by the poet, Malashri Lal. She writes mellifluous poetic prose where she pours her heart out in the language of nostalgia. This paragraph sets the tone of her entire poetic narrative in the book:

“Poetry has been my attempt to bridge the disparate inheritances. As dusk sits gently over the spiky grass of a mela ground in Jaipur, oil lamps appear at modest doorways like beacons to goddess Lakshmi. This is Jaipur of the 1960s, not the cosmopolitan tourist hub of modern times. Then, someone unfurled a Pabuji ka phar scroll, others spread a cotton dari over the sand. On the sidelines, the Bhopa singers who would render the ancient poetry of Pabuji’s exploits were preparing for their performance. Husband, wife, and the young boy wrapped their ankle bells dexterously. The man said a quiet prayer in front of the scroll, the woman pulled down her ghunghat and lit an oil lamp to hold up periodically to the scroll, the boy stretched his limbs for the rhythmic dance accompanying his father’s recital. The phar has no written script — it’s lodged in the memory of the Bhopas, their roving temple, their itinerant folk epic in pictures. Such poetry is mnemonic.” (Lal 13)

Elsewhere, Lal talks about the rich pedigree that shaped her as a poet:

“Far away from Jaipur, my ancestral families were in Calcutta and Shantiniketan, some having assisted Rabindranath Tagore in the early years of Visva-Bharati. The poetry in that context was aligned with music, woven into readings from Bengali, other works of Indian literature, and even Scottish ballads. This was an early cosmopolitanism carried further into Calcutta’s multicultural heritage manifested in abriti or recitations from many sources. I enjoyed these during visits to my grandparents.” (Lal 14)

Gender equality in poetry is an imperative and evolving aspect that Lal inevitably takes as her agenda.

Gender equality in poetry is an imperative and evolving aspect that Lal inevitably takes as her agenda. Her poetry encompasses ideas challenging traditional gender roles, biases, and stereotypes. Precisely, her kind of gender equality seeks to provide equal opportunities for all genders to be represented and celebrated. Lal celebrates the diverse perspectives of life through her poetic personae. This allows her for a more inclusive and comprehensive presentation of human experiences. Lal’s poetry challenges stereotypes, her poetry deconstructs traditional gender stereotypes and societal expectations of human beings.

To her, poetry can be a powerful tool for empowering individuals to express their experiences and perspectives, particularly for the marginalised. It provides a platform for voices that have historically been silenced. Intersectionality and a nuanced understanding of inequality are her schedules and schemas. Poetry serves as a powerful medium for her to foster dialogue, empathy and understanding on these important issues. Lal’s camera artistically, swiftly glides through the human civilization, missing nothing.

In the poem “Ardhanareesvara”, Lal writes about gender equality:

“Indivisible unity, Parvati and Shiva forever entwined Women and men interdependent, infused with traits of each other A softer left lineament draped in finery, a muscular right stretched over taut skin Artistry overlaying a deep philosophy of a shared destiny Symbols, associative of power and grace But not attributed to a dichotomous gendering. Sages, sculptors, storytellers knew the eternal truth That form belies essence much of the time Masculinity and femininity are the same word, Read in reverse To denote the other. That too is an illusion In Creation, there is only One Ardhanareesvara The God who is both woman and man. Ubiquitous, limitless reminder of equality. (Lal 21)

All that affects her, affects her home, this earth, her fellow beings, the culture she embodies, and is a part of, and the nature that surrounds her, come under the radar of her poetic tongue. She tries to be meaningful, and effective and to interact with the world through poetry. Folklore and mythology, among other things, are something she usually goes back to while writing poems. Lal writes about Goddess Laxmi in the poem “Diwali with Goddess Laxmi”:

“Today he can watch the neighbour’s lights As signs of joy ephemeral Gathering its brief glow from a cosmos Ruled by the ageless Surya Who never sleeps in his vigil Over the deluded earth. Today he will trust Lakshmi’s lineage Of wisdom from the sages Who believed in the third eye Seeing into the unseen The vaak that speaks beyond words The Aatman that never dies.” (Lal 23)

Poetry comes to her as a ceaseless mode of countenance of the innate self – both its highs and lows.

Poetry comes to her as a ceaseless mode of countenance of the innate self – both its highs and lows. The stimulation emanates from the obligation or even the impulse to express the innermost human mind, both as a self-contained vessel of thoughts and emotions and as a self in empathy with her milieu and environment. And in this, she includes all things and all objects material and non-material, animate and inanimate. Most of all, her motivation comes from the transactions that keep on happening with people around her, the inestimable vignettes of nature – both human and cosmic, and of course the different elements of thought and feeling that all these arouse in her. The poem “Krishna’s Flute” is her supreme feeling of Krishna consciousness, and the poem is for Pandit Hari Prasad Chaurasia, dedicated to the memory of the music he offered to the world through his flute:

“The sweet melody of Krishna’s flute floated Across the ominous, silent streets of the city in pandemic People huddled home in fright Staving off the invisible enemy That brought fever and delusion Breathlessness and death. The gentle notes wafted through the air Filling the emptiness of their Anxious homes — A kitchen with unlit fire A room with unmade beds That shelf with tattered clothes This face with hollowed eyes.” (Lal 24)

In the poem “Manthara Dasi”, Lal expresses her empathy for the differently-abled woman:

“What wrong did I do in protecting my child? Doesn’t every mother dream of a princess, a queen?” (Lal 27)

In the poem “Radha’s Dilemma”, Lal sings of a love that is complete surrender, ultimately platonic: “The Palace messenger said Krishna is grievously ill. Only feet-washed water from a beloved would heal Him. Is it true that Rani Rukmini and All the sixteen hundred wives refused, Saying it’s a grievous sin to Feed their charanamrit to a Husband? Curse would fall upon a woman for insulting her Patidev.” (Lal 28)

In “Sita’s Pankha”, which has a similar tone and tenure, the poem that she dedicates to Jatin Das, she writes:

“I sit at my meal, The Pankha I give to my lord Rama Gently he waves it over my thaali Of banana leaf and forest fare, Nature’s plenitude, Our household, one with my Mother Earth.” (Lal 32)

In “Sita’s Rasoi”, she points out the so-called equality and equilibrium in the society:

“Take one each little Bakha, you too. Be sure it’s an equal share, not a morsel must exceed anyone’s due. What did you say — the rotis are not exact rounds so what is an equal share? That puzzles a mathematical man who may know enough to solve this query. Uneven jagged edges, uncertainties they might mull over as Father, Priest, Teacher.” (Lal 33)

But again, the woman, who stands for the preservation of livestock, solidarity, equality and justice, concludes in the same poem in a democratic way:

“I have decreed as Mother bountiful you, my foster child, elsewhere born, look at the old texts how to divide equally these uneven pieces, No bias No trespass No waste. Food it is that holds us humans together.” (Lal 34)

At the end of the poem, Lal writes in the ‘Note’ section,

“The rasoi or kitchen is a cultural symbol of solidarity that crosses the boundaries of caste and class. ‘Sita’s Rasoi’ in Ayodhya in Uttar Pradesh, is supposedly the kitchen used when Sita came as the royal bride and cooked a symbolic first meal for her kingly family. I shift the scene to the final chapters of the Ramayana, to a rasoi in sage Valmiki’s hermitage where Sita delivered her twin sons, Luv and Kush. The boys grew up in the company of ordinary children. I imagine Sita’s maternal love for Bakha, an orphan child and the playmate of her royal sons, eating together at Sita’s kitchen.” (Lal 34)

In the poem “Ladies Special”, the pain of a common woman pulls the heartstrings of Lal. She writes in the ‘Note’,

“Pooja Devi, who was with her husband and family, complained of labour pain after which a co-passenger tweeted to the Railways of her condition, seeking help. The train was then halted at Ratlam railway station and Railway doctor Ankita Mehta attended to her at the railway station and helped her deliver the baby. (Source: Mumbai Mirror, 4 Jun 2020).” (Lal 69)

The Dalai Lama, Gandhi ji, Maharani Gayatri Devi, Rabindranath Tagore, as well as common people during Covid-19, no one has escaped the poet’s attention in this collection. The book doesn’t have a specific character, there is no inclination, no leaning, no hypocrisy. The collection is truly multifaced, multidimensional, inclusive and flexible.

There is a soothing poem, “Go Gently into the Sunset”, that talks about one’s preparedness for the ultimate truth of life. Landscape is an identity for the poet, she writes poems on Delhi dusk, Howrah bridge, Kolkata, Kashmir, Bellagio, Italy, Shimla, Landour, and all those places that have shaped her personality.

The complexity as well as the simplicity of the poems prompt Ranjit Hoskote to write about the collection:

“As we read and re-read Mandalas of Time, circling through these poems as though traversing both a physical terrain and an ethereal cosmography, we find ourselves asking: Where do the gods live now? When the mountains have been brought low by global warming, the forests denuded, and the rivers poisoned, where can the gods live now? In the same breath, these poems urge us to ask: And how do we live; by what rules, by what canon of conduct towards those others – human and more-than-human – with whom we share this planet? Shall we merely survive, or could we yet re-learn how to flourish and learn to flower with, not flower at the expense of? Let us learn from “the supple leaves”, that “Flat and curved Cradle the flowers that have no other family” (Hoskote 111)

A large part of her poetic oeuvre, especially in this collection, Mandalas of Time, is a rerouting of her personal experiences, feelings and answers to events in life and issues around her. So, the personal has been a main stem behind much that Lal has written. Hers has been a lively journeying through life – there have been elevating inspirations from myth and folklore; there have been hours of solitude just as there have been trials of fortitude and pliability. Events come and go in life – they cannot be the material for illustration in art, but the understandings one acquires through them, the realisations that dawn and the persuasions to life that are converted through every single happening, big or small – these find a place in poetic mien and gradually move on from the personal to the collective.

In that sense, Lal prefers ‘social’ over the ‘political’, because she has never needed a façade to camouflage and present her feelings. There are issues like the interrogation of subalternity, equality of gender, worries for the differently-abled, for children and the old, accepting alternative sexual orientations, realising the position of a pantheistic creed for our survival and forthcoming generations of humanity -–a variety of such thoughts that fill her mind and find expression through poetry in the collection, Mandalas of Time. She is a poet with mindfulness towards ecology and society at large. She believes a poet need not be simply a word-juggler, (s)he has a better accountability to accomplish—by playing the role of the harbinger of social transformation. Let me conclude by quoting Lal in the sustenance of my critical understanding of her:

“One may remember Rabindranath Tagore’s anguished call, ‘When I stand before thee at the day’s end, thou shalt see my scars and know that I had my wounds and also my healing.’ That, to my mind, legitimises the ‘uses’ of poetry in contemporary contexts. Through the sufferings laid upon human beings by acts of violence, not of their own making, the transcendent question about the cause has to be answered by the self too. Only poetry captures these inner dialogues, the cracked mirror of troubled consciousness, the silent cry of those who have travelled beyond tears. The language of poetry relies on its authenticity, not on a linguistic category or a region. Its value resides in principles of integrity and genuineness. Mandalas of Time is an offering to the luminosity of healing.” (Lal 18)

Cover photo sourced by the reviewer.

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

A very perceptive and insightful review! Hearty congratulations to the Poet Prof Malashri Lal for such an absorbing, heart-touching and thought-provoking volume of poetry, and to the reviewer, Prof Nandini Sahu!