Arindam, our Editor-in-Chief, traces the history of Durga iconography. Historians at Allahabad Museum opine that the stature of the Goddess grew during the Gupta period. Happy reading, Happy Puja, from all of us, in Different Truths.

Durga Puja (also, Pujo) means many things to many people. The history of iconography tells us that a non-Aryan Goddess, possibly with tribal antecedents, associated with Tantra and miracle cures (read Ojha or local Voodoo doctors), gradually gained importance and prominence.

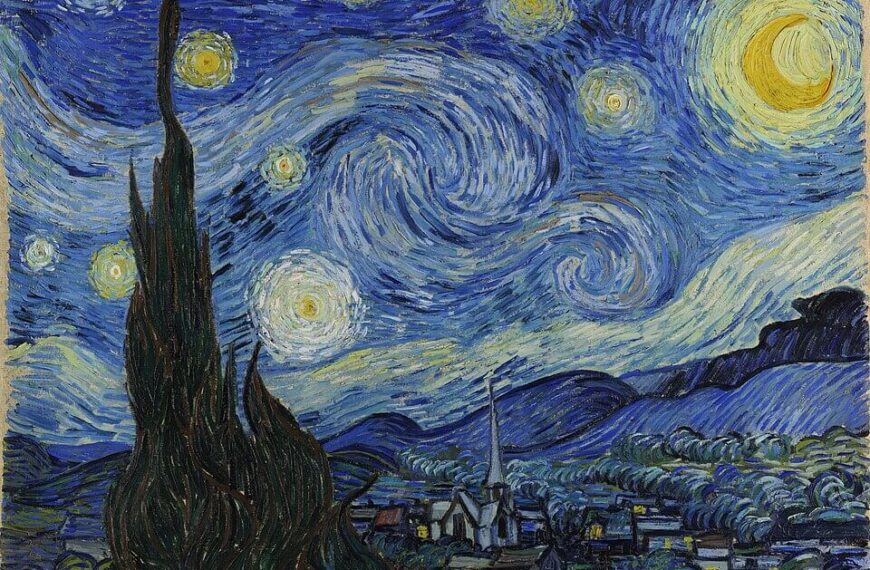

If I may digress a bit, Prof. B Mukherjee of Calcutta University, an expert on Hindu iconography, made a clear distinction between an Aryan and a non-Aryan icon, which was quoted during a seminar at Allahabad Museum, many moons ago that I attended. Mukherjee opined that all Aryan Gods have water cosmology – they are on a Lotus – standing, seated or reclining. All non-Aryan Gods, later assimilated into the Hindu religion, have hills, mountains, cremation grounds, etc., as their cosmology. Thus, we see Shiva on Kailash. Durga, the daughter of the Himalayas, is seen on mountains, while Kali, in some Tantric forms, is worshipped in Shamsan (cremation grounds). But, Lakshmi and Saraswati are seated on Lotus, while Vishnu, in yoganidra, is reclining on a lotus bed, with Sheshnaag as his umbrella, while Lakshmi, his consort, is seen gently massaging his legs.

To quote an earlier article, published elsewhere, The Lion of Durga is a Gift from a Greek Goddess, I had written in October 2007 that in the early Kushan period, around the first century AD, Durga was a lesser goddess. This period’s terracotta figurines and stone sculptures depict the goddess with two or four hands, wrestling with the demon (Mahisasur), locked in hand-to-hand combat. Most of these figurines and sculptures were excavated at Sonkh, near Mathura. It forms a rich legacy of Mathura Art. For 300 odd years, the lion was not seen during the Kushan period, opined Sriranjan Shukla, former assistant keeper of the Allahabad Museum.

He added, “The Mahisasur-Mardini icon of goddess Durga, as we see it today, evolved in the Gupta period, undergoing changes in iconography. Around this time, we find examples of Devi with eight, 10, 12 and even 16 hands. As her stature grew, her iconography evolved.

“The Gupta period is a time of transition. Referring to a sandstone relief, of the latter part of the fifth century AD, of a Chandrasala (placed outside temples to indicate the ruling deity), we see Mahisasur-Mardini combating the asura (demon). It shows the goddess placing one of her feet contemptuously on the head of the vanquished demon. She lifts his hindquarters by the tail and pins him down with her Trishul (trident). A short male figure, as her attendant, establishes her glory. He is a gana of Shiva, the consort of the goddess. The gana and the Goddess’ locks are elaborately treated in that period’s style.”

The Kushan artists of the Mathura Art School are credited with conceptualizing Mahisasur-Mardini, or the form of Durga defeating the buffalo demon. She attained glory in the Gupta period as a lesser goddess, depicted in terracotta figurines and sandstone reliefs. Most Puranas were authored in the Gupta period, a golden era of Indian art, literature, trade, commerce, and polity. It was a time of peace and prosperity.

Shukla, an expert of the Mathura Art School, explained, “The Kushan artists of the Mathura Art School are credited to conceptualise Mahisasur-Mardini, or the form of Durga defeating the buffalo-demon. She attained glory in the Gupta period, from being a lesser goddess, depicted in terracotta figurines and sandstone reliefs. Most Puranas were authored in the Gupta period, a golden era of Indian art, literature, trade, commerce, and polity. It was a time of peace and prosperity.”

Dr Sunil Gupta, an art historian, said, “It was probably in the Gupta period, between the fourth century AD and sixth century AD, that the Durga icon was introduced in Bengal. Since ancient times, the worship of the female principle has been reflected in popular terracotta art in Bengal. I have seen the famous mother goddess figurines, in terracotta, from the ancient port of Tamralipti (presently, Tamlute, in Midnapore district, West Bengal) in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. This is from the first century AD, and the icon is not that of Durga. It was only natural for the people of the eastern state to accept Durga and assimilate it into their lifestyle.”

Swami Harshananda, of Ramakrishna Math, in his book, Hindu Gods and Goddesses, says, “Lion, the royal beast, her mount, represents the best in animal creation. It can also represent the greed for food and hence the greed for other objects of enjoyment, which inevitably leads to lust. To become divine (Devatva), one should completely control one’s animal instinct. This seems to be the lesson we can draw from the picture of the Simhavahini (the rider of the lion).”

Durga, by turn, is our daughter and mother. Her vulnerability and strength mishmash in the collective consciousness. Here’s wishing you all fun, frolic, and joy for the ongoing Autumnal festivities from the ever-growing Different Truths family.

Picture: A miniature sculpture of Durga slaying the buffalo demon from Bengal, from the 12th century AD. Pala-Sena school of art. (Photo courtesy: The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

Interesting to read the chronological account of the rise of Durga through different periods of history.

Thank you so much, Baljeet ji