Ruchira explores the origins and flavours of papadums during the festive season, highlighting its transcendental nature and personal connection, exclusively for Different Truths.

During the festive season, which is still underway, I have been sampling them by the dozens and with great gusto. So, suddenly, I was seized by a quaint idea: Why not delve into the antecedents of papadum which remains an important part of Indian gastronomy? Whether consumed as a snack or as part of a major meal, papad is a delicious and versatile food that proves delightful in every bite and enjoys immense popularity across the length and breadth of the land irrespective of caste or class distinctions.

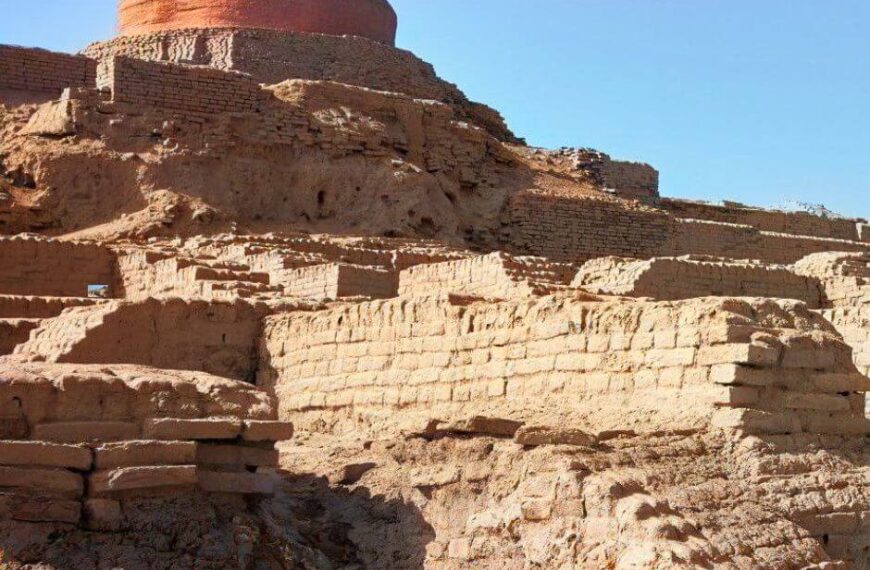

Extensive research reveals that the term papadum may be traced back to the Sanskrit word “parpaṭa” which denotes a flattened disc. According to other sources, the Indus Valley civilisation’s inhabitants created the papad for the first time more than 5,000 years ago. In that bygone era, folks of the region were believed to be in the habit of making a flatbread known by the name of “paryushan” its chief ingredient being lentil flour. Yet another theory contends that the Mughals were responsible for introducing the papad to the Indian subcontinent. The migrants from Central Asia presumably brought with them a dish called “papadum” made with powdered lentils or chickpeas.

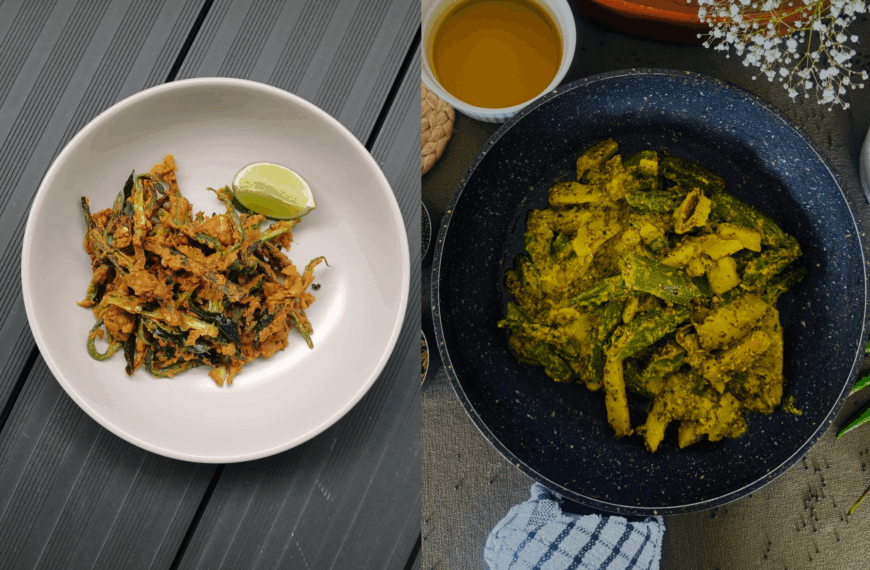

Papads may look the same, but their flavours and ingredients vary with geography and nature.

Papads may look the same, but their flavours and ingredients vary with geography and nature. Many are unaware of this subtle distinction. For instance, in Tamil Nadu, papad is made from black gram flour and is flavoured with cumin seeds and chilli powder. Sindhi papad is made with urad dal spiced with lots of black pepper, while in Rajasthan the basic components of papad include a mixture of lentil and chickpea flour (besan) seasoned with spices e.g., turmeric, cumin, and asafoetida (hing). Its origin may be lost in the mists of antiquity, but the popularity of this ubiquitous item has spread beyond the shores of India – to Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and more.

Interesting to note, as a community, the Jains are a finicky and fastidious lot. But they have taken to papad just as fish takes to water. Do you know why? They mandatorily refrain from the consumption of leafy greens, herbs and fruits during the entire monsoon phase (to avoid killing insects and other microorganisms which abound during the rains?) Consequently, their diet is restricted to grains and lentils, and voila, papad fits the bill to a tee!

Apart from lentils and legumes papad, there exists an entire range of papad made with sabudana (sago/tapioca) and rice. However, these are best eaten as crispy crunchy snacks washed down with steaming cups of tea.

Considering the nutritional angle, papad is rich in fibre and has a substantial quantity of protein and other essential nutrients.

Considering the nutritional angle, papad is rich in fibre and has a substantial quantity of protein and other essential nutrients. Additionally, it contains probiotics that promote the growth of good gut bacteria. Papad is known to prevent gastric problems; moreover, it produces enzymes and juices that help to digest food and boost overall metabolism.

On a personal note, I harbour certain pleasant memories linked with papad. My husband’s family had a long enough sojourn in the hinterland of Rajasthan. Naturally, papad quietly

crept into their daily cooking. It was in my marital household, that I had first accosted papad ki sabzi (crushed pieces with diced potatoes cooked in a light gravy) and loved it. Even today so many years later, I often cook this dish for my spouse, and sure enough it brightens his day!

Picture design by Anumita Roy

By

By

By

By

How enriching — what about the origins of roti?