Christine de Pizan, a French Renaissance writer, was ahead of her times. Feminism as a concept and a terminology emerged four centuries after her. She lived by the pen and had imagined a city for women in mediaeval France, opines Dr Nachiketa. A Special Feature for the International Women’s Day (IWD), exclusively for Different Truths.

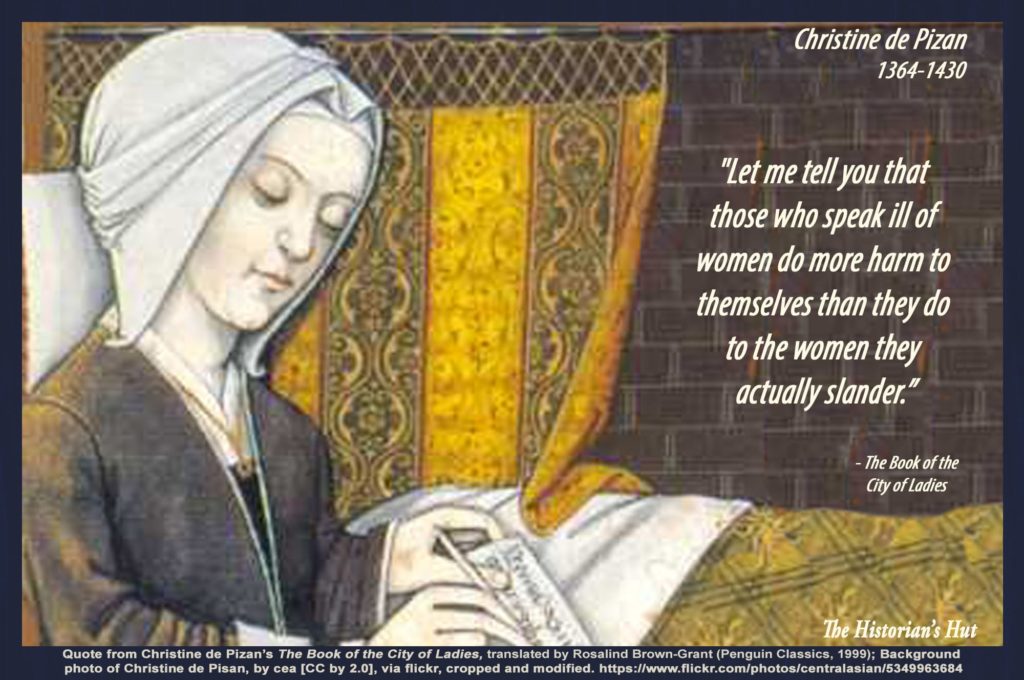

She began to address the debate about women that was happening during her life through works like Letters to the God of Love (1399), The Tell of the Rose (1402), and Letters on the Debate of the Romance of the Rose (1401-1403). These are the records to invite debate for the women because the author experienced the sweet and sour facets of her life. She became legendary authoring, The Book of the City of Ladies (1404-05), a historical novel and its sequel, The Treasury of Ladies (1405).

Meet Christine de Pizan, a French Renaissance writer, who imbibed the very first feminist concept, brushing off traditional roles assigned to women in her own ways, when women were dealt as man’s property and deprived of legal rights. She lived on commissioned work of literature for elite and royal court members and thus became self-employed to support herself and her family. Her early life left her well prepared to face future challenges. She is a poet, a historian, a philosopher, a prose writer, a feminist, and the first professional woman writer of Europe, since mediaeval times. The literary critics also failed to acknowledge Pizan, as their own, showing scholarly neglect.

She sought dignity, self-respect, distinction, and designated roles of women…

Feminism as a concept and a terminology emerged four centuries after her life. The history of feminism and the history of women placed her on the forgotten shelves. The notion of feminism, at its early age, was so like the tongue of her women’s issue, by which contemporary scholars address her as a feminist. She sought dignity, self-respect, distinction, and designated roles of women in a society which are the precursor of political, economic, and social equality, as defined by modern feminism. Her own life and times of that time, living by her pen as the first European woman, is perhaps the desired life of modern women.

She came to France from her motherland, Venice, Italy, with her father, Thomas de Pizan, as a child. She was born in Venice, in 1364. Thomas was the astrologer of King Charles V. He gave her the best education accessible in the royal environment against his wife’s consent. And he arranged her marriage at the age of fifteen to Etienne de Castel, a scholar, a royal secretary, and noble, according to the convention. She had a happy conjugal life. Her husband encouraged Christine to continue her studies till tragedy struck Christine’s life. The tragedy of deaths. Death of Charles V (1380) caused the unemployment of her father and the death of her father, five years later, in 1385, and the demise of her husband, in 1389, during an epidemic, changed everything. She was widowed at twenty-five. She survived, left alone to fend for her mother and three kids.

A livelihood by writing in mediaeval France and that too for a woman was unheard of…. It was her vocation to support her family bring up kids.

A livelihood by writing in mediaeval France and that too for a woman was unheard of. She wrote for the elites and got money in return. It was her vocation to support her family bring up kids. She disseminated copies of prose and poems to general readers for extra income. Commissioning work raised her confidence. She became recognised and famous. The reading audience made her popular. Her liberal attitude and self-sufficiency provoked her ardent readership. Christine authored a lot of works on the virtues of women, referencing Queen Blanche and dedicating them to Queen Isa beau. Christine’s influence was acknowledged by the readers, people, and authors, after her death. in 1430.

She was basically a poet in her early life, not always a stereotyped one. She emerged as an exception, making the social system dynamic in her works:

Alone am I, to feed myself with weeping Alone am I, suffering or at rest Alone am I, and this pleases me the best (Willard, 1990)

Her works like, Alone am I, ushered a new voice in the French letters. Modification of contemporary thought of the genre. In Alone am I, the poet is not in search of another lover and is resolved to endure pain. She exemplified patience and courage.

Christine developed first the concept of women through rhetoric, against a male-dominated institution…

L’Epistre au Dieu d’Amours came out in 1399. Christine developed first the concept of women through rhetoric, against a male-dominated institution to counter the courtly love attitudes, a defamatory event toward women of that period. The theme of the book was that women lodge a complaint to Cupid, (the author herself is a secretary of Cupid) about their detractors, and wished to banish such men from his court, who speak falsely about women. She challenged the misogynist Ovid, the classical poet in a surprising manner. A theological dimension is added to attack gently.

In 1402, Christine instigated a debate on the literary merit of Jean de Meun’s popular Romance of the Rose in her Querelle du Roman de la Rose. She voiced dissent against the misogynistic satire of Romance of the Rose, where women are addressed as seducers, vulgar, and immoral. After all his writing was slanderous to women.

In 1405, the civil war started in France. Christine completed her all-time great and famous literary works in tormented years, The Book of the City of Ladies (Le Livre de la cité des dames) and The Treasure of the City of Ladies (Le Livre des trois vertus).

In mediaeval France, women’s role was controlled by two authorities – the Church and the aristocracy.

In mediaeval France, women’s role was controlled by two authorities – the Church and the aristocracy. In the manual, women were means for childbearing, rearing, and domestic duties. Trades were permissible in the tradesmen family. Noble ladies could act as in-charge of the estate in absence of a husband. This way women were associated with men. But the role of women lacked a full-fledged dignity and respect for them in society. Christine desired to ensure the role of ‘aid of man’ to a ‘non-hierarchical’ concept, which was much ahead of its time, then.

Observing the women’s roles in the 15th Century, Christine authored those books as a token of resistance for the cause of women and addressed these not to men, but to women. The Book of the City of Ladies superficially narrates stories of some famous and historic women. City of Ladies was a major departure from Boccaccio’s De Mulieribus Claris (On Famous Women), following central dogma: recasting women as virtuous. At the same time, she resisted deliberately misogynistic phenomena by men through logic and reason. Male of contemporary society tagged women as vile, what she experienced through her life, she lamented. Feeling for a vile fellow, she attacks society and the philosopher in her own style keeping the femininity in her soul.

The Book of the City of Ladies is the first work in feminist historical fiction.

The Book of the City of Ladies is the first work in feminist historical fiction. It addresses the issues of opposite sexes hitherto disputed like the status of women in the sciences, and the relative differences in the physical body between the sexes. Christine opines that women have the natural ability to deal in science or perform in the scientific enterprise if society promotes them. Society had reduced its place in science. Progressive Christine said, “I realise that you are able to cite numerous and frequent cases of women learned in the sciences and the arts. But I would then ask you whether you know of any women who, through the strength of emotion and of the subtlety of mind and comprehension, have themselves discovered any new arts and sciences, which are necessary, good, and profitable, and which have hitherto not been discovered or known. For it is not such a great feat of mastery to study and learn some field of knowledge already discovered by someone else, as it is to discover by oneself some new and unknown thing.” (The Book of the City of Ladies, Translated by Earl Jeffry Richards New York: Persea Books, 1982)

Christine’s Reason’ replied, “Rest assured, dear friend, that many noteworthy and great sciences and arts have been discovered through the understanding subtlety of women, both in cognitive speculation, demonstrate in writing, and in the arts, manifested in manual works of labour.”

Tegan Zimmerman quoted arguments of Richards on the context of Pizan’s view on education –prior to Christine, no woman had spoken out in the vernacular on issues pertaining to women.

Tegan Zimmerman quoted arguments of Richards on the context of Pizan’s view on education –prior to Christine, no woman had spoken out in the vernacular on issues pertaining to women. Christine insisted that women must be educated. These two facts alone make Christine revolutionary. Her attitude was profoundly feminist in that involved a complete dedication to the betterment of women’s lives and to the alleviation of their suffering.

She comments women equal as men in natural ability, when weaker in any physical respect, having inbuilt compensatory measures. Positioning ahead of her time, Christine, six centuries later guessed scientific and sociological views on the neurological aspects of human beings.

Women are appreciated, defended, in the context of the symbolic city of Christine.

Women are appreciated, defended, in the context of the symbolic city of Christine. Ideas of three allegorical figures – Reason, Justice, and Rectitude have been expressed as emotions of figure or deity. Allegorical figures enter debate from a completely female perspective through conversations citing evidence and opinions. Christine opined women sustain until she raises voices or remains silent. In fact, for most of the women, in all three parts of the book, it would be impossible to fully emulate but is able to adapt their virtues (courage, intelligence, and faithfulness) to their own experience.

She continued challenges in The Book of City of Ladies, being on the debate, she questioned the difference in virtues of men and women, when the Church was still in power in late mediaeval Europe. She cited the Aristotelian virtue ethics, stating the theological argument that men and women are created in God’s image. Slightly, she touched the theological wing in lamentation “If God is good, how could he have created women as evil?”

A woman deserves equal privileges educationally or politically, Christine vocalises, stating equality in intelligence and culture, at par with men.

A woman deserves equal privileges educationally or politically, Christine vocalises, stating equality in intelligence and culture, at par with men. But if her sex gets maligned, the guilty feeling of ingratitude is the unique way of attack. Men should be grateful lifelong for women, who cared for them. Roles should be complimentary. Following values of the medieval era acknowledgment and respect for women is what she sought for.

Margolis, 2016 commented, “For the first time, we see in her text a history of women designed to encourage their autonomous potential and emotional or professional partnership with men, rather than one designed to keep them confined as had masculine doctrine. That is extraordinary enough, but Christine claims a political role for women as well.”

In The Treasure of the City of Ladies Christine advised women on how to mitigate the perils of the French society when patriarchy and civil war were the norms.

In The Treasure of the City of Ladies Christine advised women on how to mitigate the perils of the French society when patriarchy and civil war were the norms. Each educated woman could be an eligible resident of the city of virtue as they are capable of humility, diligence, and moral rectitude. Such women as per the daughter of God like Reason, Rectitude, and Justice. These triads are three virtues regarding women’s success.

Margolis, 2016, further commented, “…perhaps the City’s greatest contribution is its unprecedentedly accessible content, its new canon, to women of all social ranks, not just the literate aristocrats: a way of improving each class of woman by example. For the less-literate classes unable to read her words, Christine raised aristocratic consciousness of their plight and yet also their potential for redemption, an inspiration to upper-class women especially to look after the less fortunate. Her feminism never sought to deny or usurp male agency, but rather to alert women to their own powers of agency, superior or at least equal to men’s as a sort of partnership within all ranks of society and in keeping with God’s will. Yet, she never expects them to be solitary, studious ‘politicos’ like her, probably because she wishes them greater happiness.”

She too wrote along the line of the renaissance. Her style followed blending classical philosophy and humanistic ideals…

She too wrote along the line of the renaissance. Her style followed blending classical philosophy and humanistic ideals except, she wrote for women charters. She vindicated women against popular misogynist texts. Modern feminists call her an activist and a woman historian. Simone de Beauvoir mentioned in her (1949) Christine contributed for the second sex.

Tegan Zimmerman analysed the literary characteristic of historical fiction in City of Ladies to opine, “In fulfilling the third criterion of feminist historical fiction, Pisan succeeds on the level of the heroine as well as the author; both the Christine in the text and Pisan as author consciously subject patriarchal history and religion to a gender analysis which is exemplified when compared with many of Boccaccio’s tales from Famous Women, though this unfortunately not within the scope of this essay…. Pisan’s feminism in relation to rape, as Richards suggests that Pisan’s remarks on rape are possibly the first of their kind to be written by a woman and which are still relevant in the twenty-first century…. Pisan is ‘refuting those men who claim women want to be raped’ and she identifies rape as both violent and sexual.”

Scholar Jill E. Wagner (2020) comments citing phenomenon lady, Virginia Wolf, “Christine anticipated the feminist necessity of Virginia Woolf’s “a room of one’s own” but she builds on a grand scale and follows mediaeval tradition in deliberately selecting a city, not a room. While giving voice to the unvoiced, thus presenting her public with provocative new material, she adheres to an established, respectable historical model, St. Augustine’s City of God.”

Honesty and insight provoked her strong feminist leanings.

She defended women when everyone dared, or no one even thought of doing so. Honesty and insight provoked her strong feminist leanings. She was slightly away from the relational feminists, “did not advocate the eligibility of woman for every position commonly held by men” as the age deserves. Christine had steady political engagement throughout her career. Her political thought oriented from the perspective of ‘virtue ethics’ and ‘virtue politics’. Adam (2017) concluded, “Many questioned whether she could reasonably be considered a political thinker at all, that is, whether she was simply a moralist or whether her work manifested a coherent political philosophy. Today, it is widely accepted that Christine was indeed a political thinker, theorising competently on kingship, warfare, and government more generally.”

Eternal women with women issues you can find among her best-known works: One Hundred Ballads (1393 CE) , Moral Lessons (1395 CE), Letter of the God of Love (1399 CE), Letter of Othea to Hector (1399 CE),The Tale of the Rose (1402 CE), On the Mutability of Fortune (1403 CE), The Book of the City of Ladies (1405 CE), The Treasure of the City of Ladies (1405 CE), The Book of Feats of Arms and Chivalry (1410 CE), The Book of Peace (1413 CE), The Tale of Joan of Arc (1429 CE).

Christine de Pizan in The Book of City of Ladies, wrote, “Take up your pen and write. Blessed be those who will inhabit our city and swell the number of its virtuous citizens. May all of this College of Women learn Wisdom’s lesson. Our first students must be those whose royal or noble blood raises them above others in this world. Inevitably, the women, as well as the men, whom God establishes in the high seats of power and domination must be better educated than others. Their reputations will lead to great worthiness in themselves and in others. They are the mirror and example of virtue for their subjects and companions. The first lesson, therefore, will be directed at them— the queens, princesses, and other great ladies. Then, step by step, we will begin to explicate our doctrine for women of the lower degrees, so that the discipline of our College may be useful to all.”

References

- Nadia Margolis,A Feminist-Historical Citadel: Christine de Pizan’s Book of the City of Ladies

- Feminist Moments: Reading Feminist Texts. Ed. Katherine Smits and Susan Bruce. : Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 11–18. Bloomsbury Collections.

- Mark, Joshua J. “Christine de Pizan.” World History Encyclopedia. World History Encyclopedia, 26 Mar 2019. Web. 01 Mar 2021.

- Willard, C. C. Christine de Pizan: Her Life and Works. Persea, 1990

Adams, Tracy. “Christine de Pizan.” French Studies, vol. 71, no. 3, July 2017, pp. 388–400. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.1093/fs/knx129. - Zimmerman T., A Genre All of Her Own: Reading Christine de Pisan’s The Book of the City of Ladies as Feminist Historical Fiction, Academia, March 1, 2021 , https://www.academia.edu/31089402/A_Genre_All_of_Her_Own_Reading_Christine_de_Pisans_The_Book_of_the_City_of_Ladies_as_Feminist_Historical_Fiction

Visuals by Different Truths and the Internet.

By

By

By

By

By

By