Urna reviews Aneek Chatterjee’s poetry book, Of Ashes and Persiflage, exclusively for Different Truths.

The essential element of drama for Aristotle was “the plot”. About the plot, Aristotle is often said to speak of three haloed unities: the unity of action, the unity of time, and the unity of place.

However, suppose we dive deeper and analyse with a mammoth magnifying glass. In that case, these rules are not attributable to Aristotle but rather to an inaccurate interpretation of his works by the French Classicists. While Aristotle did speak of the importance of the unity of action, he only briefly mentioned the unity of time (more as a description and not as a strict, narrow, definitive proscription to adhere to). He was utterly silent on the unity of place.

The unity of time means that the play must take place over 24 hours, though sometimes it is argued to be 12 hours due to the ambiguity of Aristotle’s language of “a single revolution of the sun”.

The unity of place means a play must occur in a single location.

The unity of place means a play must occur in a single location. However, according to many experts and historians, these were not the principal points of Aristotle’s argument.

Aristotle, however, did argue for the unity of action. By this, he meant a play should focus on a single plot, everything in the plot should be essential to it, and removing anything would make it disjointed and scattered. For Aristotle, the drama was an imitative art; the thing that it is essentially imitating is a single, complete action that represents the turning point of the story.

Many historians believe that Greek theatre, mainly Greek tragedy as described by Aristotle, is taking the conception of a story, and zooming down to almost the moment just before the climax, the climax itself, and the moment just after. It’s the artistic highlighting of this single action and why it is crucial.

As I read Aneek Chatterjee’s Of Ashes and Persiflage, I couldn’t help but think of Aristotle’s Poetics and his amplification of the unity of action or the single plot, the unity of time, and the unity of place. Hawakal Publishers published it.

Chatterjee is a poet and academic from Kolkata.

Chatterjee is a poet and academic from Kolkata. He has been published in global literary magazines and anthologies of repute. He has authored fourteen books, including three poetry collections and a novel. Chatterjee has a PhD in International Relations and has been teaching in leading Indian and international universities. He has been a Fulbright – Nehru Visiting faculty at the University of Virginia, USA, and a recipient of the prestigious ICCR Chair to teach abroad. His poetry has been archived at Yale University.

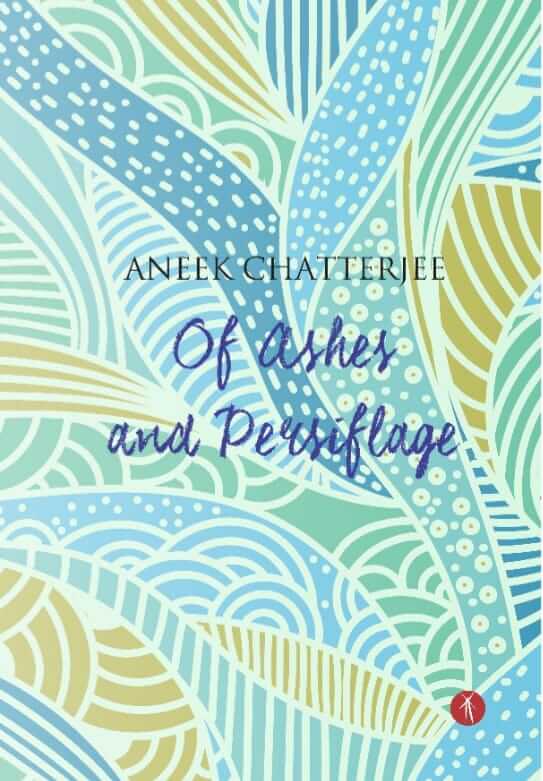

But before we talk about the unity of time, place, and action in Chatterjee’s poems, I must tell you that almost mystically, the energies of the poems resting within Of Ashes and Persiflage have been channelled onto the cover.

The cover design by Bitan Chakraborty doubles up like a wide-angled look at the singularity and the multiplicity of themes, the variegated patterns of the leaves and the foliage invite us in, the imagery lush, a regenerative upswell of energy after the dark, claustrophobic freeze of a pandemic that tore our lives apart. Like the rainforests of the Amazon, bathed in monsoon freshness, the cover of the book will cascade past your eyelashes and hold your irises captive. Fluid, welcoming, anticipatory. In stark, biting, gorgeous contrast to its title, Of Ashes and Persiflage.

Through his poetry, Chatterjee urges you to push against what you think you might know.

Through his poetry, Chatterjee urges you to push against what you think you might know. The ‘Dilapidated Wall’, the first poem in this collection of 60 poems, starts with the adrenaline rush of the train moving. Chatterjee deftly paints the picture of the pink flowers slowly moving out of the reader’s sight. The narrative of the boy who’s dark, damp vulnerabilities we can experience, as we read on.

The mention of “winter” and the locomotive, which is far more than just a vehicle moving from point A to point B, suggests that the unity of time and place converges in this stirring poem. And when Chatterjee strips away the haunting surface of fear – “the boy’s shivers” feel like the unity of the plot that Aristotle talks about.

And in winter nights,

the dilapidated wall crumbled

several times to allow dacoits

with big primitive guns.

The boy shivered in fear

till the morning whistle

of the locomotive creates

a rhythm of safety

and silent laughter.

(‘Dilapidated Wall’)Drawing on the language of afternoon greys and dark clouds, Chatterjee’s second poem ‘This Afternoon is Grey’, dismantles and challenges the canvas of a so-called, grey-drenched day in the life of a train commuter and enlarges the reader’s understanding of how that simple word encompasses so much of the human condition – “grey”.

The grey afternoon and the platform of the train station here signify the unity of time and the unity of place.

The grey afternoon and the platform of the train station here signify the unity of time and the unity of place. When the protagonist stumbles upon the realisation of his love for grey, that somehow poetically becomes the unity of action for me.

This afternoon is grey

All lights were switched on early

I know every bit of this

surreal world, brown door, every bit…

But I never knew

I loved grey so much.

(‘This Afternoon is Grey’)Chatterjee’s train poems seem personal and intimate to me in more ways than one, perhaps because I live in Mumbai, where the local trains form our veritable lifeline, the most common-sensical way to traverse unthinkable distances, as in every mega-metropolis around the world, whether London, New York, or Tokyo. Astutely Chatterjee dissects our everyday monotony-tinged myopia and gives it a more significant meaning, a refreshing dimensionality of outlook.

Chatterjee weaves in the compelling imagery of the dead in ‘Dead Men’ …

Chatterjee weaves in the compelling imagery of the dead in ‘Dead Men’ framed in photo frames with the idea of the dead talking through their eyes. Here, the lifeless photo frames seem to represent the unity of place, and the sense of losing the ones who were once alive, seems to me somewhat ironically, the unity of time—reiterating the aching timelessness of time.

The unity of action grows bone-chilling, palpable, and searing as the protagonist feels the eyes of the dead on his back. They are shifting the reader’s understanding of what language might mean for those wanting to read the eyes of the deceased.

They look at me, but they look beyond

making me turn, only to sense their eyes on my

back

(‘Dead Men’)Chatterjee further deconstructs life through the eyes of death in his poem, ‘Of Ashes and Persiflage’ …

Chatterjee further deconstructs life through the eyes of death in his poem, ‘Of Ashes and Persiflage’, sharing its title with that of the book. Chatterjee, in this poem, introduces The Iron Curtain, which was the political, ideological, and military boundary dividing Europe into two separate areas from the end of World War II in 1945 to the end of the Cold War in 1991. The Iron Curtain, for me, represents the unity of place in this poem.

Chatterjee writes, “The iron curtain separates death on both sides” the corpses on the eastern side are waiting for “the pyre” on the western side. The tireless “wait” that the corpses have to endure becomes the unity of time, and I am fascinated by how Chatterjee reinforces that even after death, the corpses have to wait for “a date with ashes”.

The finality of death and the imagery of “status, belongings, wealth and ego” burning away are the connective tissue of this poem, or as Aristotle would argue, “the unity of action”.

Chair looks at the corps

for one last time, and statu

Belongings, wealth andego watch in persiflage.

(‘Of Ashes and Persiflage’)Chatterjee’s voice is crisp, sharp, and to the point, leaving the reader much to ponder.

Chatterjee’s voice is crisp, sharp, and to the point, leaving the reader much to ponder. Chatterjee’s language and imagery are tantamount to a mix of fire and water, sunshine and persiflage, spirit and soul. Lifting the reader irrevocably higher, into spaces and domains, never entirely unimagined.

The reader becomes part of the audience, watching and witnessing, mesmerised, and drawn into the scenes, characters, themes, and motifs within Of Ashes and Persiflage. All the poems come alive in front of the reader’s eye. He was almost jumping out of the pages, assuming a three-dimensionality that Aristotle had imagined for Greek theatre.

Cover photo sourced by the reviewer

By

By

By

By

By

By

By

By