In the fifth part of the serialisation of In the Land of the Dragons, Mitali takes us on a tour of the Great Wall of China, with praying mantis, donkey, gory and glory. Tiananmen that saw the 1989 massacre saddened her. She celebrates the vibrancy of China, exclusively for Different Truths.

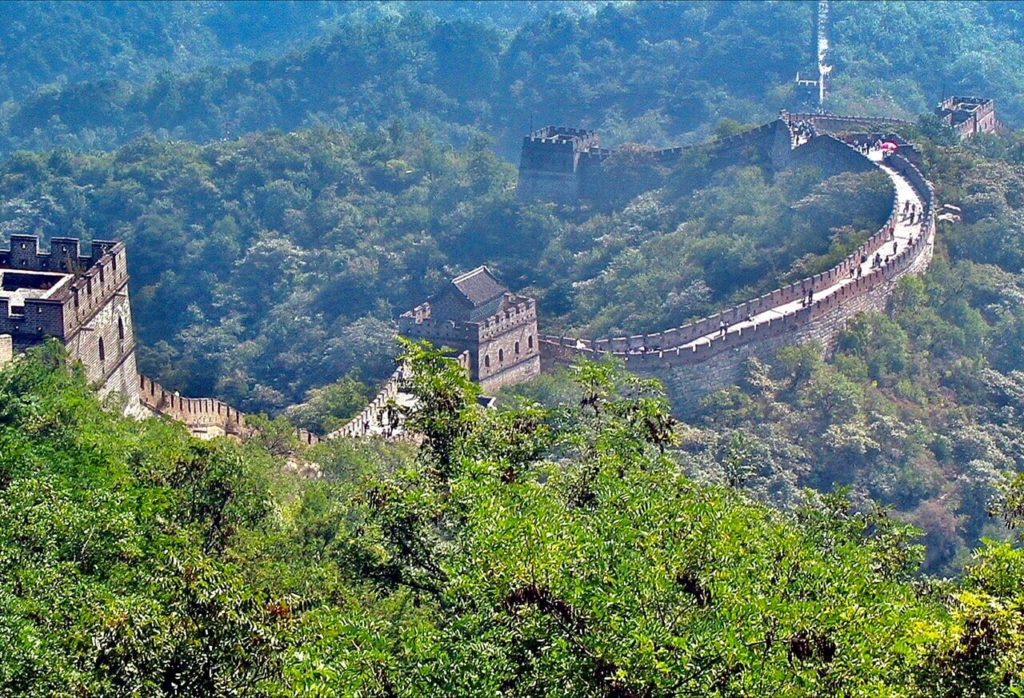

The Great Wall has drawn stories and travellers through ages with its continuity and endlessness. There was something about the Great Wall that made it truly spectacular. Perhaps the historicity and human endeavour that went into its making. Perhaps it was the feeling of antiquity and longevity lying beyond the scope of everyday human perception that made us cherish this snakelike wall that curls and winds its way over a large part of China, unifying it with its silent presence. We had visited this legend four times while in China.

The Great Wall spans 2000 years of construction and an endless sense of length1. Estimates of its length are between 1500 and 5000 miles. The materials vary from mud to sturdy stone. It starts in Mongolia and stretches to the coastal town of Shanhaiguan on the Yellow Sea…that’s nearly upto the Korean Bay. It has a history that encompasses endless eras and endless tears. Thousands of labourers were buried under the wall through the ages. It encompasses stories of cruelty and legends of achievement and of loyalty. It has been much written and fantasised about. It has been painted by numerous artists in different styles. They have made films on it, even Bollywood movies2. And of course S. T. Coleridge’s famed Kublai Khan3 refers to it.

- Twice five miles of fertile ground

- With walls and towers were girdled round.

When I was finally on the Great Wall the first time, I felt this crazy sense of exhilaration coupled with euphoria. I could imagine ancients, especially unwashed Mongols, giving out blood-curdling whoops, riding on their sturdy horses, with both the horses’ and riders’ manes flying wild – riding to invade the plenty in China. I could imagine delicate, frightened princesses hiding, sheltered, and cocooned by the hardy soldiers behind walled mansions, protected not just by the walls of their palaces, but by the Great Wall, which grew greater with the tears and blood of the common man, who laboured to give his land the ultimate protection from invaders. I had tears in my eyes and also felt a sense of achievement because this was something I had wanted to do from my teens, and we finally did it the first time when I was past forty. And whenever I visited Beijing, I liked to repeat the experience.

The Great Wall was built to protect and unite the people of different kingdoms from invaders: the Huns and the Mongols and other aggressive tribes outside the bounds of the Chinese empire. One of Aditya’s humanities teachers referred to it as “a wall to pen in the sheep”. But I think it’s bigger than that. The Wall has become an embodiment of the Chinese spirit of endurance and hardship through the ages.

The Great Wall was built to protect and unite the people of different kingdoms from invaders: the Huns and the Mongols and other aggressive tribes outside the bounds of the Chinese empire. One of Aditya’s humanities teachers referred to it as “a wall to pen in the sheep”. But I think it’s bigger than that. The Wall has become an embodiment of the Chinese spirit of endurance and hardship through the ages. It is a ballad to the blood and tears of the common population. It also upholds certain Chinese values that are unique to the nation. It makes China into what it is today.

The Chinese protected the country that was the centre of their universe (Zhong guo or central country) from invasion by different cultures and traditions. While the rest of the world intermingled, the Zhongguoren (the people of the centre of China) remained apart. Unlike its neighbour India, China for a long time was untouched by world events. I don’t know if that’s good or bad. Some people may call the Chinese insular. But I think their seclusion built up their inner resilience in a way that has helped them survive even the onset of COVID-19. It is not that other nations do not survive or suffer. But staying for eight years in China, made me realise how different it was. Sometimes I would see fleeting similarities to the typical Indian in the common man, but that’s because they were both human and children of two great nations with immense history. But while China was the untouched centre of the world, India was the hotpot of all cultures. To be an Indian is unique as to be a Chinese. The blood of most of the races around the world combined in the veins of India, to create the concept of India4. This variety gave the country a richness of texture and uniqueness just as being pristine had given a distinctive flavour to China.

The Great Wall was a profound experience every time we were on it. We drove down from Beijing. There are six entry points to the Great Wall from Beijing alone. The most popular is Badaling, with the statue of Jiguang Qi1, the Ming dynasty’s major architect. This man visualised and created what most people know as the Great Wall. He was a soldier and a creative visionary. He worked for ten years on the Wall. Then he fell out with the emperor and died in ignominy.

The Great Wall was a profound experience every time we were on it. We drove down from Beijing. There are six entry points to the Great Wall from Beijing alone. The most popular is Badaling, with the statue of Jiguang Qi1, the Ming dynasty’s major architect. This man visualised and created what most people know as the Great Wall. He was a soldier and a creative visionary. He worked for ten years on the Wall. Then he fell out with the emperor and died in ignominy. However, his vision was so ingenious that it was realised even after he died, and today we have his dream listed as one of the wonders of the world.

On our first visit, we went to the entry point at Mutianyu. We went up on a cable car to the foot of the Wall and then climbed the steps. Ha! We were there at last. When we got there, we realised that though it was the end of September, it was warm and sunny. We wanted Surya, then four years old, to take off his sweatshirt and jacket. Since Surya was fond of that outfit, he set up a wail of protest cum indignation. It lasted till we went through the crowds and arrived in an open area with cannons on the wall. Surya’s protest gave way to the admiration of the cannons. There was peace at last.

My husband and Aditya photographed the Great Wall and the fabulous scenery around it. I gazed beyond, dreaming as much as I could, till Surya expressed a desire to relieve his bladder. I had seen a Chinese boy of about five using the gaps in the wall to relieve himself, but somehow, that seemed a bit incongruous. So, we decided to descend at the next exit to the mountains below. On the way, Aditya informed us his needs were similar to his brother’s.

My husband and Aditya photographed the Great Wall and the fabulous scenery around it. I gazed beyond, dreaming as much as I could, till Surya expressed a desire to relieve his bladder. I had seen a Chinese boy of about five using the gaps in the wall to relieve himself, but somehow, that seemed a bit incongruous. So, we decided to descend at the next exit to the mountains below. On the way, Aditya informed us his needs were similar to his brother’s. As we went down the steps and on the mountains, Aditya spotted a donkey. He was excited and kept shouting, “Mamma, gadha, gadha … gaa-dhaa … gadha.” A gadha is a donkey in Bengali, our mother tongue. Surya was equally excited. He went close to the donkey and probably would have pulled its tail if we hadn’t stopped him in time. My sons grew up in Singapore before we moved to China and were unfamiliar with donkeys except in the zoo. Both my boys were excited to see the donkey, which stood patiently on the hillside, gazed at infinity and grazed in the shadows of the Great Wall.

We returned to the Wall. Now it was time for hunger. The boys had a banana each. We bought them from a vendor on the wall, and they were really expensive. Then it was time to photograph the praying mantis sitting and chirruping on the parapets. There were not just a few, but many of them, sitting at various points. We got off the wall in a chair that descended on a suspended wire, no less risky than what we faced later in Guilin and Singapore, I feel. Maybe God was training me for future rides.

Surya talked excitedly of the donkey. So, I asked him, “Did you like the donkey more or the Great Wall more?” Promptly the answer came: “Donkey!” As we all started laughing, he edited his statement and said he liked both equally! Well, that’s a four-year-old trying his hand at diplomacy.

We lunched at a restaurant called the Schoolhouse. This was a memorable experience too. We sat on the terrace and gazed at the Great Wall while waiting for the food to arrive. Surya talked excitedly of the donkey. So, I asked him, “Did you like the donkey more or the Great Wall more?” Promptly the answer came: “Donkey!” As we all started laughing, he edited his statement and said he liked both equally! Well, that’s a four-year-old trying his hand at diplomacy.

Then I was overcome by a terrifying experience. I found a giant praying mantis perched on my lap! As I screamed for help, paralysed with fear, Surya laughed with glee, while Aditya and my husband focused their cameras on my lap. My husband asked me to hold still, as he feared the praying mantis would fly from its perch. Everyone thought it was funny that I screamed. Well – everyone except me. After all, none of them had a giant praying mantis sitting on their laps! Finally, a waiter from the restaurant came to my rescue and shooed the insect off, saying it brought good luck.

I achieved a sense of immense satisfaction from walking on the Great Wall. I wanted to go back to it again and again. Next time I wanted to go to a different part – maybe Simatai, the part of the wall that’s supposed to be most picturesque. Or maybe, Shanhaiguan, where the man-made wall comes to a halt in view of God’s inimitable creation – the ocean.

I achieved a sense of immense satisfaction from walking on the Great Wall. I wanted to go back to it again and again. Next time I wanted to go to a different part – maybe Simatai, the part of the wall that’s supposed to be most picturesque. Or maybe, Shanhaiguan, where the man-made wall comes to a halt in view of God’s inimitable creation – the ocean.

We did go back to the Great Wall a year and a half later, but not to any of the places I had thought of returning to earlier. This time we went to Juyong Pass. We surfed the Net and found that Simatai required good hiking skills. With Surya being six years old, a difficult hike was not a feasible proposition. And Shanhaiguan did not seem to have suitable hotels close by. We needed one where we would be assured of a good Western breakfast, a minimal requirement for the three men in my life. We could find only some Chinese hotels there. A bowl of rice porridge is not exactly the kind of breakfast my adventurers can survive on. So we went back to Beijing.

We started out for Badaling, the most popular gateway to the Great Wall. The scenery was breath-taking after we left the town behind. It was a bit cold and foggy for April, but we were familiar with the global changes in weather patterns back then too. There was this fabulous winding river and hills, just like in Coleridge’s poem. On the hills, we saw the Great Wall stretching proud and long.

We started out for Badaling, the most popular gateway to the Great Wall. The scenery was breath-taking after we left the town behind. It was a bit cold and foggy for April, but we were familiar with the global changes in weather patterns back then too. There was this fabulous winding river and hills, just like in Coleridge’s poem. On the hills, we saw the Great Wall stretching proud and long. We liked it so much that our driver suggested he would take us there instead of Badaling.

This was Juyong Pass. It was fabulous, like out of a picture book. There was an uphill climb. We could not go very far because Surya felt cold. In the city, the temperature was about 13 degrees Celsius. And here the temperature had dropped to 7 degrees Celsius, and there was a cold wind blowing. Higher, it was 6 degrees Celsius. Again, we had no choice but to head back. But we did explore the lower reaches – the bridges; the tunnels; the offices, where the Chinese Army officials would sit and plan their strategy; and of course, the cannons. Surya made a lot of funny faces and poses on the wall. We also bought some souvenirs and T-shirts for the boys with a picture of the Great Wall and writing saying, ‘I Climbed the Great Wall’. After all, they had both climbed the wall twice at a very young age, and that is quite an accomplishment.

There were no eating places around. They had a coffee shop, but its unsanitary condition would have required major compromises that we were not willing to make. So we went back to town for a late lunch.

My first experience of the Great Wall was breath-taking. The next time, it was scenic and heady with historic details, but we could not stretch out our time as we did at Mutianyu, for we were unprepared for the temperature difference between the Great Wall and the city. I had been eager to go to Badaling because I wanted to meet the ghostly Ming dynasty general Qi riding his steed at the frontier of the Great Wall.

My first experience of the Great Wall was breath-taking. The next time, it was scenic and heady with historic details, but we could not stretch out our time as we did at Mutianyu, for we were unprepared for the temperature difference between the Great Wall and the city. I had been eager to go to Badaling because I wanted to meet the ghostly Ming dynasty general Qi riding his steed at the frontier of the Great Wall.

The third time, I did see the ghostly rider at Badaling. Qi on his steed appeared to be a short man. Except for the statue, this was my first experience of wanting to be off the Great Wall. Not only was it crowded and touristy, but most of the crowds were aggressive. They pushed and jostled. A long white tunnel that led from the cable station to the Great Wall reminded me of labour camps and concentration camps. There were cable cars at one end and the remade Great Wall at the other end. It. It was cold, windy, and crowded in the tunnel. I spent more time queuing in it than walking on the Great Wall.

Badaling was a big disappointment. I was so claustrophobic in the crowds that I could not enjoy the walls stretching out beyond. I think this is one attraction in Beijing that is grossly overrated. Though I must say I loved our Mutianyu and Juyong Pass Great Wall experiences.

Badaling was a big disappointment. I was so claustrophobic in the crowds that I could not enjoy the walls stretching out beyond. I think this is one attraction in Beijing that is grossly overrated. Though I must say I loved our Mutianyu and Juyong Pass Great Wall experiences.

I saw Badaling as an interlude in my romance with the Great Wall. I did hope to go to other parts of the Wall to relive the splendour I experienced the first two times.

In fact, the fourth time, I went back to the Great Wall at Mutianyu with my mother-in-law – who, despite her bad knee and inability to walk much, climbed the Great Wall and looked like she had conquered all the Mongolian hordes. It was more congested with the October holiday crowds than during our last visit four years before. It had more restaurants, and they were building a new access. But still, it held its charm intact. That was the time we went to Beijing by the train that moves at an average speed of 290 to 300 kilometres an hour, and we reached the capital within five hours. We covered a distance of 1379 kilometres in record time. Though the scenes seemed to rush by, they captivated the eye with their ever changing landscape. We could perceive the difference between north and central China.

An interesting way to experience Beijing is to take rickshaw rides through the narrow, old-fashioned alleys called hutongs. The good thing about these rickshaws was that they were automated, so the rickshaw drivers were not burdened by our weight – especially mine. It was lovely sitting on a crimson velvet seat and driving through alleys flanked by houses that were a few hundred years old. The experience had a flavour of antiquity with the comforts of modern technology.

An interesting way to experience Beijing is to take rickshaw rides through the narrow, old-fashioned alleys called hutongs. The good thing about these rickshaws was that they were automated, so the rickshaw drivers were not burdened by our weight – especially mine. It was lovely sitting on a crimson velvet seat and driving through alleys flanked by houses that were a few hundred years old. The experience had a flavour of antiquity with the comforts of modern technology. Mind you, the rickshaw driver who had the crimson velvet seat was enterprising. He caught us outside the Temple of Heaven. We were near the boundary wall, some distance away from the gates. When we said there were four of us, and his rickshaw was too small to accommodate us all, he called his friend on the mobile. He had caught us on one side of the crossing. As we crossed over the overpass and came down to ground-floor level, he was waiting for us with his friend, who had a covered box-like rickshaw. We were forced to surrender, including the cash: 20 RMB for about 400 metres.

The Temple of Heaven is the largest wooden structure surviving from the 1420s5. It is impressive and intimidating, especially when you see the markings for leading the sacrifice to its ultimate end. It has the dragon and phoenix motif running through its carvings and paintings. There is something pagan and daring about the spirit of this temple.

The Temple of Heaven is the largest wooden structure surviving from the 1420s5. It is impressive and intimidating, especially when you see the markings for leading the sacrifice to its ultimate end. It has the dragon and phoenix motif running through its carvings and paintings. There is something pagan and daring about the spirit of this temple.

The park surrounding the temple had cypress trees, lush lawns and a variety of birds. There were trees with whirls on their bark, reminiscent of Van Gogh’s Sad Cypress. The whirls were only on the bark, though, unlike the cypress paintings. The trees were labelled “Old Trees” in Chinese, said both of my sons. On our way back, we chased a beautiful blue-grey bird, and Aditya captured it with his camera. The other interesting thing in the park was music. Some people were singing karaoke in Chinese, and some played the erhu … all at the same time … and no one seemed irritated by the others’ music. On our way back, we even heard blaring Hindi movie songs, the kind I do not like. People were doing line dancing to that.

One has to say the rickshaw drivers were superb. They found us … again. This time they took us to Tiananmen through the hutongs of Beijing. That cost us another 80 RMB. A normal taxi ride covering the same distance would be less than 30 RMB – probably closer to 20. We paid for the flavour and experience, I explained to my husband as he told me irritably that we could have taken three taxis for the price he paid. The men earned their pay with their enterprise and glib tongues. Some people, like my husband and sons, would have noticed open dustbins in the hutongs. I only saw the antiquity and flavour.

The word Tiananmen means “gate of heavenly peace”. A bit of a juxtaposition because it was immortalised by the massacre of 1989 to the world6. The gathering took place near a pillar or obelisk-like structure which is supposed to be the Monument to the People’s Heroes7, a place where crowds often gathered to mourn and protest8. Another interesting feature near the pillar is the two dioramas outside Mao’s mausoleum (‘Carry the cause of our revolution through to the end’9) depicting workers marching towards an ultimate victory. The expressions on their faces are of anger.

The word Tiananmen means “gate of heavenly peace”. A bit of a juxtaposition because it was immortalised by the massacre of 1989 to the world6. The gathering took place near a pillar or obelisk-like structure which is supposed to be the Monument to the People’s Heroes7, a place where crowds often gathered to mourn and protest8. Another interesting feature near the pillar is the two dioramas outside Mao’s mausoleum (‘Carry the cause of our revolution through to the end’9) depicting workers marching towards an ultimate victory. The expressions on their faces are of anger. The statues are vibrant and make one think. It makes me wonder: Can a movement borne out of largely negative feelings give way to positive thought processes and a positive, holistic society?

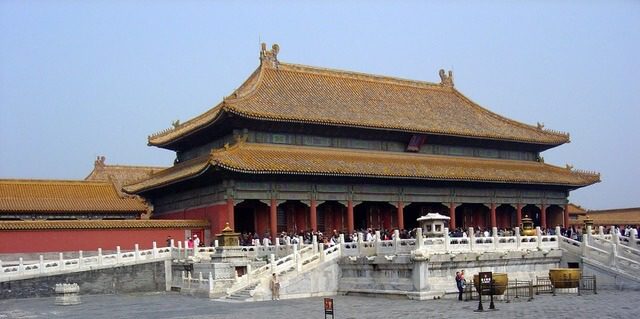

This area captures different eras in history with artefacts and architecture. The roof of the six centuries old Forbidden City10 preened over the walls of Tiananmen, which gave way to the Mao Mausoleum and the diorama, bringing us right up to less than a century-old history. It is like having a view of more than five hundred years of history together.

We went to the Forbidden City the first time and heard all the stories and saw the remnant artefacts. All the stories related to us by the guide seemed to reflect an opulent and hedonistic lifestyle without any greater movement.

We went to the Forbidden City the first time and heard all the stories and saw the remnant artefacts. All the stories related to us by the guide seemed to reflect an opulent and hedonistic lifestyle without any greater movement. Normally opulent hedonism at least yields some beautiful art, music, or culture. But the life that was exposed to us within the Forbidden City seemed to be largely opulent and sensuous only. What was interesting was that the guide claimed that the Forbidden City was initially constructed in Nanjing and moved stone by stone to Beijing. I wonder how long this took? Or did the story11 evolve because Nanjing was the capital before Beijing?

References

- 1. The Great Wall: The extraordinary history of China’s wonder of the world by John Man, Bantam Press, 2008

- 2. https://www.thehindu.com/features/cinema/China-in-Bollywood/article16880378.ece

- 3. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43991/kubla-khan

- 4. India: A History by John Keay, Harper Collins Publishers India, 2000 & The Travels of Marco Polo, Wordsworth Classics of World Literature, 1997 edition

- 5. https://www.chinahighlights.com/beijing/attraction/temple-of-heaven.htm

- 6. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/reference/modern-history/how-protest-tiananmen-square-turned-into-massacre/

- 7. https://www.tripadvisor.com.sg/Attraction_Review-g294212-d1793502-Reviews-Monument_of_the_People_s_Heroes-Beijing.html

- 8. https://ramblingwombat.wordpress.com/2017/02/26/chairman-mao-memorial-hall/

- 9. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monument_to_the_People%27s_Heroes

- 10. https://www.chinahighlights.com/beijing/forbidden-city/

- 11. https://www.chinahighlights.com/beijing/forbidden-city/history.htm

Visual by Different Truths and photos by the author

By

By

By

By

By

By