In this updated chapter, Mitali tells us about oranges, Buddhas and sports, giving us a glimpse of China with humour and wit. An exclusive for Different Truths.

Oranges have always held a special place in my life. When we played the game, I always feared breaking an arm during the tag. If you are wondering what I am referring to – it is the tag that followed the game based on the nursery rhyme Oranges and Lemons1, though I think the rhyme we recited in India might have been different from the one that you find online. At the end of the game, there was a tag between the two teams. The two teams (oranges and lemons) would collapse on the ground during the tag. I was never a great sportsperson and my arms were always weak. Maybe that led to my distaste for oranges. I avoided them. But then, China changed so many things, including my distaste for oranges. This is how it happened.

We went for a trip with Aditya’s best friend’s family to an island that grew oranges and tea in the middle of a huge lake called Taihu.

We went for a trip with Aditya’s best friend’s family to an island that grew oranges and tea in the middle of a huge lake called Taihu. Antonio, Aditya’s best friend, was the same youngster who painted a face on the egg and kept a pet egg2.

As we approached his village, we could see orange orchards dotting the hills of the island. It looked beautiful. On two sides of the narrow road was the huge waterbody, lapping its waves as if impatient to lick the juice of the oranges growing on the hills of its islands. We were two families, Indian and Italian, going to a traditional Chinese village to pick oranges from an orchard with another American child in tow (Antonio’s brother’s best friend).

A hospitable, aged Chinese lady let us tour her house. She gave us some green tea that grew at the feet of the orange trees in her orchard. The kitchen was a small, dark room with little space for movement. It had a built-in circular stove and utensils fitted to the stove, as it seems that traditionally, the Chinese do not wash some of their cooking utensils. She even had oranges growing in the land attached to her house. Visiting was a quaint experience for us, and the mistress of the house was friendly and hospitable. She looked fifty but was closer to one hundred.

As we sipped tea, our boys had already started attacking the oranges on the trees near the house. It was time for us to go to the real orchard.

As we sipped tea, our boys had already started attacking the oranges on the trees near the house. It was time for us to go to the real orchard. We carried huge baskets to fill. The five boys, aged thirteen to five, were practically fighting to get at the oranges. They climbed with and without ladders and filled the baskets with excitement and enthusiasm.

With our baskets filled, we headed back. Some of the villagers carried our baskets. We started exploring the countryside. It was open, green, and clean to start with. We collected resin from trees whose names we had never heard. The locals said that they made medical decoctions out of the resin.

The boys were running all over and making discoveries. They found some interesting black stuff on the ground, which turned out to be grease from the trucks that had started intruding into the village as part of the building team. We were not told what exactly they were developing in these parts. However, we learnt from our guide, a large part of the younger generation had left to find work in neighbouring towns. Much of the village was empty.

Perhaps what we call civilisation and modernisation is another way of life, and it is as intolerant of what was past as the traditionalists are of the present and the future.

Perhaps what we call civilisation and modernisation is another way of life, and it is as intolerant of what was past as the traditionalists are of the present and the future. Coming from a country of mainly villages, I feel what we call development is subjective. For us, what is a necessity may not be a necessity for others; it could even be an imposition.

Take the case of a separate bathroom, which is a must in my scheme of things. Such a thing did not exist in the traditional Chinese house that we saw. In the home of the old lady who was hosting our party that afternoon, there was a toilet bowl with full flushing mechanism in the middle of the bedroom itself. No cumbersome walls or doors separated it from the sleeping area. It was right at the foot of the bed. But then, they had chamber pots under beds in Europe at some point…Toilet habits perhaps make for bizarre discussions and I would prefer to leave that unwritten!

Our kind hostess thrust sacks full of oranges and potatoes on us free of charge when we were heading back. These oranges were seedless and like manna from heaven. I, who normally do not like oranges, could not stop eating them. We distributed these among all our neighbours, drivers, maids, and others. And yet we didn’t run out of them. In a country like China, this is an unusual experience, as you need to pay for everything first. “Pay first, consume later” is the motto of this largely affluent government. Affluence and poverty, I feel, are defined largely by a person’s state of mind and culture. You can call a glass half-empty or half-full. You could be an optimist who feels that the morning sunshine is God’s plenty or a pessimist who sees the sun as a cause of cancer, UV radiation , headaches and heat. You could weigh your riches, God’s sunshine or lucre and then decide which makes you happier.

This lady of the orange orchard definitely thought of herself as affluent, so she was happy to share her wealth with foreigners.

This lady of the orange orchard definitely thought of herself as affluent, so she was happy to share her wealth with foreigners. She was one of the most impressive, independent, and enlightened women I had come across, though she spoke only a Chinese dialect and probably had had minimal schooling, if any. She lived through her childhood in the same village before the Maoist revolution, when literacy was not seen as imperative to earn a living.

There was a beautiful sunset along Lake Taihu as we drove back from the village to the city of Suzhou. It was like molten gold with splashes of rich orange juice brightening its intensity. The island visit had been my first brush with an orange orchard.

And then, in my last house, we had this orange tree, which evidently never had fruits. We watered it regularly and we did have fruits. They were as good as the ones from Taihu. We ate and distributed. It was an amazing experience – plucking oranges from our own backyard and eating them!

Another fabulous fruit we learnt to relish in China were peaches – huge, succulent, sweet, and round. Peaches from the neighbouring town of Wuxi were famous.

Another fabulous fruit we learnt to relish in China were peaches – huge, succulent, sweet, and round. Peaches from the neighbouring town of Wuxi were famous. We bought some the first time from a roadside vendor while returning home with my visiting parents. The peaches came in around the start of summer in late June, and the season ended sometimes in September.

We bought the peaches on our way back home from seeing the Lingshan Buddha3 in Wuxi. The Buddha at Wuxi was more than eighty metres tall. It towered against the Maji mountains, casting its blessing over a historic thousand-year-old temple. Though the Buddha was built around 1996, it added to the grandeur of the antique temple and its surroundings. The other thing worthy of viewing here was the bathing ceremony performed on a concealed statue of the baby Buddha. A statue of a chubby child representing the toddler Buddha revealed itself as a metallic lotus in the middle of a huge fountain unfurled to music. Then as the statue revolved, the water spurted higher to drench not only the Buddha but also the crowds in front. Devout Buddhists often treat this water as holy as Hindus do the Gangajal (water of the river Ganges).

In Suzhou, we had an ancient Buddhist temple called Ling Yan temple in the water town of Mudu. The view from the hilltop was fantastic. I still remember a monk who helped us find our way to the temple on top of a steep hill and disappeared mysteriously. He was very excited when he saw us and insisted on calling us mother and the little Buddha from India. I do not know which one of my sons he was alluding to, but I am guessing, it was Surya as he was obviously the little one!

When we went back the second time with my husband, we discovered the temple had a lovely garden at the foothill with peacocks.

When we went back the second time with my husband, we discovered the temple had a lovely garden at the foothill with peacocks. There were some ancient Indian artefacts too in the temple. It was evidently founded by an abbot called ‘the light of India’. We were not clear about the Indian connection but there was something there.

I remember, after savouring the views and exploring the temple as we walked back to the car, we came across various vendors, including a palmist, who insisted on telling my future. He wanted his palm crossed by a red note, which meant 100 rmb. We were forced to give in. A crowd collected as he foretold a glorious future for a laowai or foreigner.

He said I would be very happy when I turned sixty! Now, I look forward to reaching sixty so that life unfurls its excitement and the foretold surprise. What could it be? Will I become a princess with silver blonde locks – I had hoped to convert to a golden haired one as a child! Or, most excitingly, will I become a grandmother and have the opportunity at last of spoiling babies rotten – like my parents did to my sons?

In this temple, the statues were not spectacular but there was an aura about the journey to an ancient building…

In this temple, the statues were not spectacular but there was an aura about the journey to an ancient building and the stories of India that gave this complex a fascinating uniqueness.

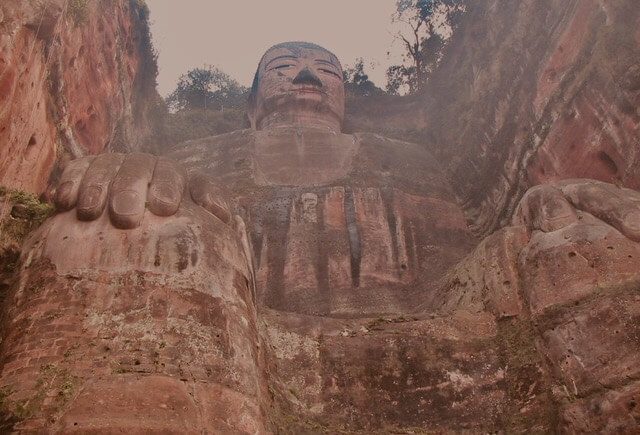

The other truly spectacular Buddha in China was the Leshan Buddha. Located about 200 kilometres from Chengdu, the capital of the earthquake-prone Sichuan, this Buddha was famous as one of the world’s largest4. It took almost two hours to trek up and down the length of this sitting giant. The statue carved into a mountain by a benevolent sage and his disciples during the Tang dynasty period was 71 metres in height. It took almost ninety years to complete. Its builders carved a gigantic Maitreya Buddha to control the waters of the turbulent river, which would overturn the boats with its torrents. The large quantity of rubble from carving the Buddha was thrown into the river to calm and divert the current. This made life easier for those who were dependent on boats for transport to an area unconnected by roads in those days.

The Leshan Buddha with its ancient heritage, caves and trickling water streams seemed to be part of a larger whole, from an eternal time beyond walls drawn by borders, cultures and faiths. The structure generated a sense of omniscience and omnipresence of God in nature. The ancient sage and his team, with their benevolence for mankind and their faith mingled with technical skill, could well typify what we look for in a modern-day scientist or engineer.

If the climb down to the foot of the Buddha was vertiginous, crowded, and narrow, the climb up, where his head started, took one’s breath away, literally and figuratively.

If the climb down to the foot of the Buddha was vertiginous, crowded, and narrow, the climb up, where his head started, took one’s breath away, literally and figuratively. The view was fabulous when you dared to stop and look around– stretching across the water to the skies. The stairs were steep, ancient, and narrow, with a low parapet. A fall would end in a quick journey to the heavenly Buddha’s abode! But the complex thronged with crowds. What was amazing was most of the tourists were local. Some of the visitors were very old, maybe even octogenarians.

Chengdu, where we were located while visiting the Buddha, was an unusual town. It had faced major earthquake tremors, but its buildings and the town remained unfazed by repeated natural disasters. It was a tough town — a town that could rear up its head and stand on its own. Though this prosperous capital of Sichuan had stores with designer and branded labels and a highly evolved local transport system, very few foreigners were visible in and around Chengdu. The locals here did not bend over backwards to please foreigners as they did in other parts of China. Most of the restaurants outside big hotels were Chinese. Where we lived in Suzhou, there were many Western restaurants and shops catering to the laowai’s needs and many nationalities.

Chengdu housed ancient history too. They had a museum that reiterated the antiquity of China. The Jinsha civilization museum5 houses digs and artifacts that date back to the 12th century BCE. In the museum, lies the holy bird in gold that has become symbolic of the Chinese heritage. Gold and ivory relics from the ancient Shu dynasty and an extraordinary gold mask also sit within the museum. We even saw the digs from where they were retrieved. It was an impressive site.

Just as the Chinese, interpreted Christmas in their own way, the expats interpreted the local lore in their unique way.

I remember we went to Chengdu in December, when Christmas celebrations took precedence for many. Just as the Chinese, interpreted Christmas in their own way, the expats interpreted the local lore in their unique way. One of these festivals was the dragon boat festival traditionally celebrated in the fifth month of the Chinese lunar calendar – which the laowai interpreted as a rowing race.

For followers of the Gregorian calendar, it fell in May or June. The Dragon Boat Race centred around a two-thousand-year-old legend of a poet named Qu Yuan6. The patriotic poet jumped into the waters of the Yangtze when his country was occupied by the state of Qin. People were greatly distressed and threw dumplings and eggs into the river to tempt the fish away from getting at his body. The annual Dragon Races commemorated the death anniversary of Qu Yuan. Google recently yielded two more stories around the race, the names and the areas varied, but the idea was the same – tempting the fish away from the bodies of the people who jumped into the river. I have not quite figured out why the boats are made to look like dragons or why they row to the thumping of drums. Expat women exercised and practiced round the year for these races. Boats and teams sponsored by different countries raced down the lakes in Suzhou. But, I wonder if the participating expats knew of the legends. Nothing about why the race originated is explained in any of these stories. But Chinese narratives are a bit like that. There is an old sitcom in Singapore, called Under One Roof7, where fun is made of this abstruse aspect of Chinese storytelling with the father relating a story with a moral that does not connect at the end of every episode.

Sometimes, I wonder if we look into the stories behind all our sports – like oranges and lemons, cricket (always wondered if it was named after the insect or was it the other way round) or football (a sport that can injure people but happens to be very popular) — what would we find? Research showed cricket originated in England from a game similar to what we call gulli-danda in India in the 1600s8. And now people all over the Commonwealth countries are obsessed with it.

Football is a game that has fascinated our family – my sons, their dad, their uncle, and others.

Football evidently originated even earlier some 3000 years ago9. Football is a game that has fascinated our family – my sons, their dad, their uncle, and others. When my eight-year-old told me with determination that he wanted to go for the football team trials, I was not too excited. He had been playing football in the school soccer club every Saturday morning. I had not been thrilled to bits about it but was quite tolerant as he needed to let off his excess energy. But trying for the under-nine team was another matter. They played matches and had a team manager, whose picture with panda poop in his hand was on my iPad. He was the one I did not want to shake hands with, the teacher who had accompanied Aditya and his group of ten to the panda reserve near Chengdu. I had also seen him blow his nose on the football field. Another coach once spat on the field. None of this seemed sanitary or well-behaved to me.

When I tried to complain to Aditya’s principal, who coordinated the Saturday morning football, he smiled his and said in a most insincere tone, “Oh, did he? I will have a word with him about it.”

When I complained to my husband, he said, “What? You complained about it? You must be crazy. Where did you expect him to spit?”

It looked like if you played football, you did not need to have a handkerchief or a tissue, could be dirty, and forget all hygienic practices and good manners.

It looked like if you played football, you did not need to have a handkerchief or a tissue, could be dirty, and forget all hygienic practices and good manners. Well at least they had improved because 3000 years ago, the captain of the losing team was sacrificed to Gods9. Maybe the pandemic will force the players to exercise hygiene and caution — though ideally we should not have had a pandemic to learn this lesson. Looking back at the stage of world history and man, I would still dare to agree with Swedish academic, Hans Rosling10: the world is improving despite the pandemic, despite the slowdowns, despite death and disease. We are better off than we have ever been before and will only continue to improve.

References:

1 https://www.wikihow.com/Play-Oranges-and-Lemons

2 https://www.differenttruths.com/humour/chapter-1-globalisation-in-our-backyard/

3 https://www.chinadiscovery.com/jiangsu/wuxi/lingshan-grand-buddha.html

4 https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/giant-buddha

5 http://english.jinshasitemuseum.com/About/Introduction

6 https://www.chinahighlights.com/festivals/dragon-boat-festival-history.htm

7https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0199280/

8 https://www.icc-cricket.com/about/cricket/history-of-cricket/early-cricket

9 https://www.footballhistory.org/

10 https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20190111-seven-reasons-why-the-world-is-improving

Photos by the author and visuals by Different Truths

By

By

By

By

By

By