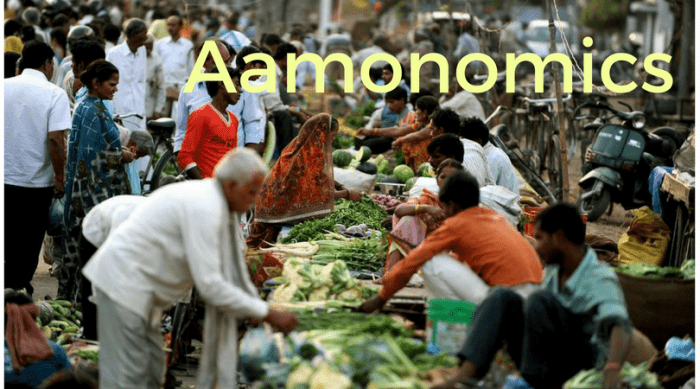

The Modi government wants to be quick to implement its rural empowerment agendas through a technological transformation in the farm sector. The hitch is that it will not be a universal panacea and will leave small and marginal farmers out of the ‘big kitty’ of mechanised farming. This is an area the government seeks to redress. The announcement in the Budget was aimed at improving the lot of 70 percent of the population living in rural areas, points out Navodita, our Associate Editor, in the weekly column. A Different Truths exclusive.

The NDA is preparing a blueprint to offer people universal access to social and economic services. Ahead of the elections in 2019, this step is seen as a major initiative by the current government. According to some official sources, the PMO and the top brass of the central government is giving shape to these initiatives to correct imbalances across regions and social strata.

The government wants to be quick to implement its rural empowerment agendas through a technological transformation in the farm sector. The government wants to turn projects like universal digitised soil health cards, soil health solutions into a reality. The government is also raising a host of equipment leasing machines to push for farm mechanisation. The hitch is that it will not be a universal panacea and will leave small and marginal farmers out of the ‘big kitty’ of mechanised farming. This is an area the government seeks to redress. The announcement in the Budget was aimed at improving the lot of 70 percent of the population living in rural areas. Some say it could be achieved through leveraging Digital India to increase digital penetration by next year. The government had taken several steps to set up WiFi facilities in villages across the nation, make India as the number one startup destination and improve port infrastructure and efficiencies. In the education sector, the government aims to end the enrolment gap for minorities, girls, Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. It seems the government has very ambitious projects. However, there is already much damage done to the rural economy by the government in the last four years.

Coming at a time when the distress in the rural economy is at its peak in more than a decade, this budget is also at variance with the government’s own assessment of the challenges of reviving the agrarian and rural economy in the Economic Survey 2018, presented in the same week. While stagnant incomes and deceleration in agricultural output characterised the rural distress, it has been made worse by the collapse of the rural non-farm economy which is equally important for driving the rural economy. It not only affected the self-employed in agriculture and non-agriculture but also affected the casual manual labourers with real wages declining for agricultural labourers as well as non-farm labourers. The commitment to uplift the economy is not matched by budgetary allocations.

Coming at a time when the distress in the rural economy is at its peak in more than a decade, this budget is also at variance with the government’s own assessment of the challenges of reviving the agrarian and rural economy in the Economic Survey 2018, presented in the same week. While stagnant incomes and deceleration in agricultural output characterised the rural distress, it has been made worse by the collapse of the rural non-farm economy which is equally important for driving the rural economy. It not only affected the self-employed in agriculture and non-agriculture but also affected the casual manual labourers with real wages declining for agricultural labourers as well as non-farm labourers. The commitment to uplift the economy is not matched by budgetary allocations.

While farmers’ incomes stagnated, the drought of 2014 and 2015 also contributed to increasing distress in the rural economy. It was only the third instance of a back-to-back drought since independence. But it came at a time when the rural economy was under stress. What made matters worse was that the stagnation in farmers’ income also coincided with the decline in rural wages in rural areas. With self-employed as well as casual workers accounting for almost two-thirds of rural workers witnessing lower incomes, it also contributed to a fall in rural demand and the rural non-farm economy. Real wages for agricultural labourers have declined at 0.3% per annum between 2013 and 2017, whereas non-agricultural wages have declined by 1.1% during the same period. Hence we can say that stagnant real incomes for farmers and declining wages along with a slowdown in the non-farm sector have contributed to a rural economy that is under stress. In most cases, loss of income has also resulted in mounting debt among farmers. In most states, farmers and youth are on the streets protesting against the government. While Tamil Nadu farmers were in Delhi protesting against the indifferent attitude of the government, farmer protests were organised at a large scale in Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh.

In the case of Madhya Pradesh, protesting farmers were fired upon in June 2017 resulting in the death of five farmers. The total number of rising farmer protests were recorded at 628 in 2014, 2, 683 in 2015 and 4, 837 in 2016. The demand from most farmers has been for some mechanism of ensuring stable and remunerative prices for the produce and a loan waiver to deal with increasing debt. There have been protests by the agriculturally advanced groups like Jats in Haryana, Patels in Gujarat, and Marathas in Maharashtra.

It’s high time that the state governments address the issues of farmers, else it may prove to be the  problem area in 2019 elections. One of the important indicators of the neglect of structural issues and the lack of seriousness of the government in responding to agrarian distress has been the decline in agricultural investment during the tenure of the present government. While loan waivers in some cases may have provided relief to the distressed farmers in some regions, it has come at the cost of a decline in investment across states on agriculture and rural development. Although some work has been taken up in developing rural infrastructure especially rural housing scheme and rural roads, it is certainly too little too late to have any significant impact on the rural economy. The empty rhetoric is also unlikely to materialize in political gain. The government needs to act fast on this front, else it will soon see 2019 victory slipping away out of its hands.

problem area in 2019 elections. One of the important indicators of the neglect of structural issues and the lack of seriousness of the government in responding to agrarian distress has been the decline in agricultural investment during the tenure of the present government. While loan waivers in some cases may have provided relief to the distressed farmers in some regions, it has come at the cost of a decline in investment across states on agriculture and rural development. Although some work has been taken up in developing rural infrastructure especially rural housing scheme and rural roads, it is certainly too little too late to have any significant impact on the rural economy. The empty rhetoric is also unlikely to materialize in political gain. The government needs to act fast on this front, else it will soon see 2019 victory slipping away out of its hands.

©Navodita Pande

Photos from the Internet

#RuralDevelopmentOfIndia #ModiGovernment #PromisesToKeep #Aamonomics #DifferentTruths

By

By