With grit, faith and hard work, she built a whole new world for herself literally out of thin air. But when Jharna was attacked by the forces of Evil, will these means suffice or will she have to devise new weapons to combat them? Here’s Sutapa’s novella, as part of the Special Feature, exclusively on Different Truths.

Rajat kicked the stand of open shelves stacked with kitchen utensils. A wok and a steel plate tumbled down and rolled to her feet with a loud clatter. But nothing could drown his enraged bellows, ‘I want the money. Do you hear?’

In a voice hoarse with weeping through a dreadful night, Jharna pleaded, ‘Where will I get so much money?’

‘I don’t care. Just get it. Sell this house. Do anything…whatever. Get me the money. Just get me the money. I want money…lots of it.’ Stumbling against a table on the way out, he vanished into the predawn gloom, slamming the outer door violently. The entire room quivered in the aftermath of his explosive outburst.

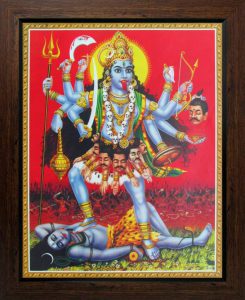

Once again, tears began to course down Jharna’s cheeks. Her back ached and the rough concrete floor dug into her hips. She rested her head against the wall and looking up at the naked iron rafters, sobbing, ‘Haven’t you given me enough misery, Ma Kali? Did you have to turn my son into a devil too? Rajat…oh my Rajat…’ Pulling up her knees, she covered the face with her palms and gave in to her grief. Alone and bereft, the figure swayed with paroxysms of inconsolable weeping that went on endlessly until no more

tears were left. Bedraggled with swollen eyes and lips, she dragged herself up into a large bed that stood in the centre of the room and curled up on it.

Whenever circumstances in life went beyond her control and they often did, Jharna submerged herself in childhood memories of the village by the Bhagirathi River. Even tonight, the involuntary attempt to extract a painful thorn, telescoped Jharna to her father’s boat gently bobbing on the river. Acrid, the smell of tar-smeared wooden boards stung her nostrils. An eight-year-old child, she lay on the deck, her cheek pressed to its uneven surface. Her father had wanted to sail when darkness was still punctured by

stars and the mist rising from the waters obscured the banks. She had been asleep on the mud-packed floor of their two-room hut. He had scooped her up in his strong arms, sinews bulging from hauling nets all day and walked the few yards down the pier and into their fishing doongie.

Keen to take in the sights and scents of the dawn breaking on the Bhagirathi, Jharna scrambled up. Cool sea breezes had blown away the mist and gold ribbons swirled on the horizon. The girl inhaled long gulps of the river’s essence spiced by whiffs of underwater life and saltiness. Nothing beats waking up to the tang of the breeze blowing in from the delta. The dip and pull of the oars under her was comforting.

Waves softly swished against the green mouldy wooden sides of the doongie melding with her father’s baritone floating down the river. Wielding a long pole to push the boat to the centre of the waters, he gave full-throated vent to a lilting fisherman’s ditty. The river echoed back his song. Midstream, her father flung the nets in a wide arc across the green waters, soft sunlight rippling on his burnished copper muscles. Little Jharna loved watching the nets stir like a live creature as hundreds of big and little fish were snared in them. Once the nets were hauled up, the decks would sparkle with the silver dance of leaping fish. Her father would sort out the bigger catch and tell Jharna, ‘Throw back the small fish and spawn. We must wait for them to grow big.’ Jharna loved diving into the nets and digging out the squirming little ones and sending them back home. She always wondered if their mothers waited for them just like as her’s did; praying to the deities for their safe return.

As always the salve worked its enchantment bringing in its wake tranquil timelessness. Peace descended on the supine form. Whether it was fishing trips with her father, the sound of her mother husking paddy, the picture of their village of a few mud huts surrounded by golden rice fields and the constant lullaby of gurgling Bhagirathi, they never failed to restore Jharna’s equilibrium. Slowly, she sat up. Tears caked salt runs down her face. Gathering up the thick, wavy hair tumbling over her shoulders in both hands, she twisted it into a loose knot. She got to her feet and went outdoors to the cemented tap enclosure. From a brimming bucket, Jharna sluiced her face several times. Cold water revived her and she could feel her pragmatism resurface.

Emotional reactions were an indulgence Jharna had long given up; ever since they had taken away Manush’s inert figure shrouded in white cloth. Manush, her husband of nine years; handsome, laughing, gentle, invariably kind… who had loved and protected her. Even now she could see his young brothers lifting the bier to their shoulders with difficulty; he had been a tall, strapping man…the best. Fate, envious of their contentment, had sent a rampaging bull into the rickshaw he was riding home after selling their paddy to the wholesaler. Manush toppled from the swerving vehicle and hit his head on a rock. Hardly could it be called an accident for the boulder had been small but sufficiently fatal. Jharna could never understand why it had happened to her; why had she never guessed how fragile her world had been. It had taken only a little boulder to crush it like a mynah’s blue egg in a child’s grasp. If she had known she would have taken greater care; at least sucked it into her soul so that later she could relive the

memories of her lost life. As it is, even Manush’s face was becoming difficult to recall nowadays.

Turning towards the open doorway Jharna regarded her home. A large single ground floor room, it was part of a row of double level tenements. There were five similar rows behind it separated by narrow alleys. In most places, the alley width was reduced to a ten-inch path due to open drains and piles of rubbish taking up space. Most of Delhi’s illegal shanty towns were built this way. Nevertheless, the room had come at a price of two walloping lakhs ten years ago. Jharna had somehow scraped it together with loans

and the money from her husband’s share of family land. It probably cost more now; how much more, she didn’t know and anyway what was the use of knowing. The room was mortgaged to the local moneylender.

Right now, it was entirely in disarray having borne the brunt of Rajat’s rage. Jharna’s entire household had been neatly arranged within the whitewashed walls of the room. It was large enough to be divided into three sections. The kitchen on the right side was separated by an open wooden shelf holding utensil, condiments, and supplies. Many of the furnishings were handouts from Jharna’s employers combined with some innovation. She had picked up an old wooden door thrown away by one. Balancing it on four stilts made from bricks garnered from a construction site, it became her cooking counter. It held a gas stove, a cutting board and the mortar and pestle. A small fridge and a cast-off- repaired washing machine stood to one side. On the left of the room was an enclosed space cut off from the rest of the room by two stout but roughly-hewn wooden cupboards. It was like an alcove and held a folding table spread with a lace doily and small figures and frames. They were Jharna’s precious deities. There were several but the central focus was a framed photograph of a Goddess Kali idol. Daily a freshly-plucked blood-red hibiscus bloomed at her feet. The cupboards held her and Rajat’s clothes. Centred in between the kitchen and the alcove was a large bed with a carved wooden head. When Jharna had moved into this first home of hers, her parents had gifted it to her. It had accommodated herself along with her son and daughter, ten-year

old Rajat and fourteen-year-old Shampa for nearly five years. But once Rajat became fifteen, he wanted his own cot. Jharna bought one cheap at the weekly bazaar. She squeezed it behind the high carved head of the bed and the wall behind attempting some privacy for her son. Now Shampa was married. So only Jharna slept in the big bed.

Sighing at the chaos, Jharna hitched up her sari and set to bringing some order. She was too tired to go to work. The seven different families who had hired her cooking services will have to manage their meals for that day. For the next hour, she swept, swabbed, dusted and washed. Eventually, the room was as spotless as before and reeked of detergent and antiseptic. Spending her days in luxurious homes of her employers, Jharna had become too used to their squeaky cleanliness. She could not bear the stink that wafted from the open drains and refuse heaps dotting the alleys of the colony. Every month she spent a few precious rupees of her hard-earned wages on cleansers for her home; the same that she saw being used in those homes.

By the time she had bathed, lit incense sticks and placed the sacred blossom at Kali’s feet, the sun was high in the sky. Jharna sat on the light-dappled doorstep combing her hair. Before her lay a packed-earth courtyard whose perimeter was lined on the other three sides with earthen pots or old oil tins bearing plants in various stages of growth. There were cacti, ferns and flowering bushes such as hibiscus, lilies, and jasmine. Green chilies and tomato plants vied with a pumpkin creeper bearing tiny fruits. Usually, this

tiny garden brought her great pleasure but today her mind was elsewhere. However, Jharna’s countenance had an earthiness that naturally blended into this pastoral scene. Looking at her, what instantly caught the eye was her blue-black hair curling to the waist and her large, dark, intense eyes. When one looked into them for a while, one discerned a fire burning deep within them. The heart-shaped face with a widow’s peak had a coppery sheen; so similar to her father’s bronzed visage only her complexion was liquid honey. Recently, fine lines fanned out from the corners of her eyes testimony to forty-five odd years of anxiety, sorrow, and hard work. When she smiled, a gap in her front teeth only added to her dusky loveliness. In fact, Manush used to say her smile, gap and all, made his insides melt. Of medium height, she was still as slim as when he had first seen her at eighteen. She had been dancing at a chaau performance in the village; the elegant style and strength, hardly seen in women dancers, making her an instant focal point. Though the chaau is traditionally danced by men, Jharna’s uncle owned a dance troupe that included women dancers. He had noticed her graceful movements when she was still a girl and persuaded her parents to let him train their daughter. Jharna loved the vigorous whirls, sways, and leaps off the chaau but she especially enjoyed enacting Goddess Kali’s victorious battle with the demons. But what had drawn Manush to her was none of this. It had been a certain look about her; maybe a reflection of her dormant resilience or spirit. There was a quiet dignity about the girl that he had never seen in one so young. Whatever it was, Manush had lost his heart forever. The essence of that

resolve and character was even more pronounced now. Walking to and back from the housing complexes where she worked, Jharna had to only turn and give a stern look to the roadside teases lining the alleys for the whistles and catcalls to dry up. Eyes turned aside when she passed by.

Her hair had dried and she rolled it into a knot. It was time to indulge in her favourite pastime; cooking. From a young age, culinary skills were her special area of interest. She relished mixing ingredients, trying out recipes and innovating new ones. When Manush’s parents came home with his offer for her hand, Jharna, only sixteen then, had brewed them cups of tea spiked with cinnamon. Her special concoction had been greeted by amazed exclamations of approbation making her blush. All his life with her, Manush would never eat a meal not cooked by her if he could help it. But today, as she washed and set the rice to boil and started chopping carrots and beans, the knife flashing intermittently, the task was not as pleasurable. Her mind was seething with Rajat’s strange tantrum. She could not understand it. In her mind, she went through the events ever since Rajat had hammered on the door last night around 3 am. Sleepily, she had got up to let him in. But he had been a bull on a stampede.

It had taken some time for drowsiness to clear and she had realised that Rajat was furious about something. But for the life of her, she could not make head or tail of his rantings. All she could understand was that he wanted ten lakh rupees. ‘For what? Why?’ These were questions he was deaf to. Rajat wanted the money and quickly. That was the bottom line. Rajat had been in and out of trouble since he had left school but he had never behaved so insanely before. She tried to reason with him but he was trapped

in a world of his own inside an insulated, soundproof capsule. Nothing she said got through to him. He had only one tirade: ten lakh rupees! Somehow, Jharna couldn’t reconcile herself with Rajat’s inexplicable behavior. Something was wrong, somewhere!

But what?

Of course, Rajat had never been a model son. The city’s attitude of ‘grab the best and to the hell with consequences’ had affected him just as it had the thousands of teens in Delhi. It didn’t matter what their economic or social status was. Making money by any means was their only aim. Despite bowing to this value system, Rajat’s empathy with his mother went deep. He would poke fun at her ethics, blithely ignore her rebukes, take advantage of her affection but under his devil-be- damned air he respected Jharna and

her efforts to make a life for them in this city so far from their village. One thing both her children had never done was to demand anything from her; they never asked for money. They were aware of the tribulations she faced daily to earn enough to care for them. So what made Rajat suddenly so insensitive? Why this unreasonable tantrum? Why did he ask me for money and such a lot of it? Jharna’s head spun with these questions and more.

Her thoughts went years back when they had brought Manush home. He had looked as if he was sleeping. The heavy bandage around his head was the only odd thing about him. Rajat had been only five and he loudly demanded of his father the toy aeroplane promised to him from town. Shampa was four years older and was aware that her father’s laughter would no longer boom in their tiny hut. And she? She had felt nothing. All she could do was stare with dry eyes at her prone husband and try to come to terms

with the fact that Manush would no longer touch her, smile at her, tease her or love her.

After the daze dissipated leaving a permanent ache where her heart was, the reality of her situation had dawned on Jharna. She had to give up her small hut to the landlord whose fields Manush had been tilling as a tenant farmer and move into her father-in-law’s home. It was a bigger cottage but there were two more sons and their families living there. Her own parents had moved to a faraway city called Delhi. Bhagirathi had changed course over years and fishing was no longer profitable work. Somebody had advised her father that Delhi would have more job options than nearby Kolkata. So now, Jharna could not even take a tempo-rickshaw to her childhood village.

It had come home to her as slowly as most unbelievable facts do that the three of them were a burden on the family. For the sons, one eking a living on the family lands and other a factory worker, they were three more mouths to feed for free. Even if Manush’s brothers were respectful of their elder widowed sister-in-law, their wives made no bones about their resentment. Manush’s mother was dead and his ailing father had no say in the matter. At first, Jharna buckled in. All day and well into the night, she would hardly

leave the kitchen. Cooking was her medium and she would turn out the tastiest dishes, beverages, and sweetmeats seeking a way into their hearts. But it did not work as she expected. The point of no return came the day Rajat, just turned seven, had asked for another piece of fish at lunch. Not only did was he refused, his aunt flung a hot poker at him along with abuses. Rajat had screamed as the poker singed his arm. That night, Jharna slept very little. White-hot fire had inflamed her as she silently raged; life cannot

be for begging crumbs. After all, Ma Kali has given me a life. She will light my way. I will make a world in which my children can live with respect. Ma has given me hands and feet. I am young. I am strong. Ma will bless me only if I make use of her gifts. It’s time to break my bindings and set sail. After rocking the whimpering boy to sleep, she had packed up whatever little they owned. Next morning, amidst amazed looks of her sisters-in-law and pleas of Manush’s brothers, a stony-faced Jharna had walked out of

her husband ’s home, her children on either side. She had caught the next train to Delhi vowing never to return.

Her parents had relocated recently to a new tenement colony in West Delhi. These were rooms provided by the Delhi government in exchange of lean-tos erected on the banks of Yamuna that it had appropriated. Though the area had problems of sewage, electricity, and access, at least the double rooms were brick and mortar and so weather-proof. It was a tight fit when Jharna had landed there with her children but her parents were ready to help. Her mother said, ‘Don’t worry, Jharna. Many new housing complexes with tall towers of apartments have been built in the vicinity. Every day, families are

moving into them. They need helpers for cleaning, washing, and cooking. You will get a job there.’

Jharna had looked doubtful. She had never worked in people’s homes. She mulled, how will I take orders from strangers? Would they treat me kindly?

Her father, who ferried people on a cycle rickshaw that he rented from a man, had shrugged, ‘In the city, if you are not literate or skilled, its manual labour for us, Jharna.’ But her mother had patted her back. ‘I work in these homes. It is not hard work like tilling the fields. Most of the ladies speak politely and give me my due. If you work honestly, people value you. You will do well. Mark my words, Jharna,’ she assured her daughter. Her father had sniffed disdainfully. Like Jharna, he didn’t like working for

people.

That night Jharna thought deeply. Silently, she asked the Goddess Kali, ‘Should I take this up, Ma?’ She closed her eyes to focus on the idol of the dark divinity residing in their village temple. Unbidden came to a thought into her prayers, you have to start somewhere…to make your life. Jharna believed it was Her answer. And anyway, what options do I have? A couple of days later she accompanied her mother to an apartment. A party was being thrown there and there was a great deal of preparation to be done.

Her mother wanted a helping hand. In the kitchen, Jharna had scoured the dirty vessels and silently watched the lady of the house struggle to bind mutton cutlets with egg and flour batter. She offered to help. Soon the lady gave up the entire lot to her. Observing Jharna’s deft hands moulding and frying golden brown crisp cutlets, she had realised that this was a master at work. The lady asked her to cook the rice dish too. By the time, Jharna and her mother left the house, it was filled with the aroma of a delectable pulao. When the dinner guests chomped through the succulent cutlets and took several helpings of the pulao, leaving the other dishes nearly untouched, Jharna’s job in this home was secure. Not as a helper but as a part-time chef.

After that, there was no looking back. Her reputation as an accomplished chef de cuisine spread far and wide. She started working at multiple homes across assorted housing complexes. Often ladies would accost her while she ran from complex to complex to complete her jobs for the day requesting she considers cooking in their kitchens. She had already enrolled her children in the nearby government school. In just a couple of months, Jharna could afford to rent a tenement not far from her parents’ home and move into it with her children. In one corner she placed a photograph of her dusky Goddess on a rickety table. Everything else was on the bare floor: cooking, eating and sleeping. Workdays were grueling but she resolutely kept her sights on her beckoning dream. All she saw at the end of the dark tunnel was a life of reasonable comfort and financial independence for herself and her children. Summer or winter, in the dense darkness Jharna would be up cooking breakfast, the noon meal, preparing the children’s

snack boxes. Then she would wake Shampa and Rajat, push them to bathe and ready themselves for school. She would sweep, swab and clean her home before she locked up. All three would start walking down to the main road when the sun would be just peeping through the trees or the sky pale in winter. She would hurry the children through the school gates and stride off to her first cooking post. Days and nights coagulated into mind-numbing drudgery yet Jharna always found time to light the joss sticks before Ma Kali’s icon to seek her blessings. If there was a crisis, she sent up a prayer. The solution,

when it came around, Jharna would attribute to Her benevolence.

Nevertheless, her path was not easy. She was thwarted in many ways. Sometimes they were the wolves who prey on lone working women in the carnivorous city. One of her first employers was an old couple. They were generous and often gave her portions from the freshly-cooked meals she prepared for them. Jharna was grateful as it saved her both the effort and expense of at least one meal for her family. The old lady loved to gossip and Jharna listened sympathetically. Their harmonious relations continued for nearly two years until their son arrived from the USA. His roving eyes soon fixed on the comely Jharna. Whenever he was home while she cooked, he would find reasons to loiter close by. Whether for a drink of water or to a request for a cup of tea, it was an opportunity to brush against her or lean over her. Jharna bore the humiliations silently out of a sense of gratitude to his aged parents. But one day he grasped her bottom from behind as she reached up for a spice bottle. She turned around and slapped him so hard that he fell down. Jharna had marched into the old woman’s room and told her everything while announcing she quit that minute. She had not even gone back for the wages they owed her.

At other times, a spiteful gardener of a complex would accuse her of thievery or an envious co-worker would fill the ears of a mistress with false tales. But Jharna was able to slip through their plots safely. She also learned much from the ladies who appreciated her work. One opened a bank account for her explaining that it would help her to build savings for a needy day. She was convinced she owed everything to Ma who was looking out for her.

This routine had continued for the next three years until a letter arrived from a sympathetic relative about her father-in- law’s demise. Written in the hand of the village scripter, it told that the land that had belonged to her father-in-law was to be divided among the brothers. It ended by saying, ‘Jharna if you want your son’s share, you have to be present at the time of appropriation. Or you will lose it all. Your brothers-in-law are counting on the fact that you will not come.’ Having encountered sticks and stones

that are accorded a lone woman struggling to survive in this world, it was a bolder Jharna who decided to stake her claim to her son’s inheritance. Her father accompanied her as she took the next train home, leaving the children with her mother.

Manush’s family could hardly believe their eyes. They could not reconcile the self-assured woman facing them with the defiant girl who left them three years ago. In the midst of the crowd, she demanded in a soft but firm tone, ‘What is the distribution?’

The second brother was reluctant to pass on the information but was forced to uphold family prestige in the presence of village elders. He unfolded the documents and showed her the allocation of his father’s land for the two brothers and only a bit for the elder grandson.

Shocked at their perfidy, Jharna exclaimed, ‘Why? That is not even one-fourth of the total property!’

‘That is all your son will get. Shares are being made according to the number of children each of us have. Dada had only two but Choton and I have five children each,’ he had said sullenly.

‘What? That is not the law. I want the patwari to divide the land according to the law or I will go to the police,’ Jharna flatly declared. One of her employers in Delhi was an advocate and she had coached Jharna well.

Her father observed her, pride filling his old eyes, as Jharna threatened and coerced both her brothers-in-law. Eventually, with the patwri as a witness, Jharna received the deeds of her husband’s one-third share of his father’s property. The very next day, she sold it to her sympathizer in the village at the highest going rate in the region. Not a paisa less. She instructed him to transfer the funds immediately into her bank account and held on to the deeds.

When her mother had called back at the patwari’s home, the only one with a phone in the village, that the money had been transferred, Jharna handed over the deeds. Now that she had safely extracted her son’s inheritance, she could turn away from the family that had treated her so degradingly. She booked her return ticket for the next day. That afternoon, she took her father to visit their old village walking among the tall coconut palms along the receding banks of the Bhagirathi. Her brother had stayed back in their

old village and invited them for a meal. News of Jharna’s triumph had spread far and wide and even to their village. Her family was proud of the way she had shown her deceitful brothers-in-law their place. As they were leaving, her niece gifted her with a Chaau dance mask. It was a mask of Goddess Kali. Jharna was so touched that tears had sprung to her eyes.

‘Why are you crying, Pishi? I know you used to dance the Chaau at village festivities,’ her niece said.

‘That was long ago; before I married your Pishemoshai,’ Jharna had wiped her eyes with the corner of her sari.

‘Yes. We heard how you hypnotised Manush Pishe by your dance,’ laughed her niece. ‘Go on with you, you little minx,’ Jharna had playfully pulled her niece’s plait but she was pleased that people still remembered her dancing in the village. On the train, she took special care with mask keeping it out of harm’s way in the crowd of passengers. When she returned to Delhi, Jharna instantly approached her landlord. She knew that he had a large room in the front row that he wanted to sell. She had had her eye on it for some time. He had quoted an astronomical sum of two and a half lakhs. After a lot of wheedling and coaxing, he knocked off fifty thousand. But even then two lakhs was a lot. Her husband’s property had brought her just a lakh and thirty. She had scrimped and saved some. There were about forty thousand rupees in her account. She needed thirty more. She hated handouts. But with no other way out, she went to her employers for loans. Three of them obliged agreeing to deduct installments from her wages. One

winter evening, she moved with the children into her own home.

By and by, she paid off the loans though it had bound her to the service of the lenders. Her parents had bought her the big double bed and she cooked on a kerosene stove placed on the floor until piece by piece she was able to buy some second-hand furniture or what her employers discarded. Over time, Jharna saved enough to add more amenities such as a gas stove, a fridge, and a TV. The precious chaau mask, Jharna had hung on the wall facing the bed. Each morning, when another day of backbreaking toil

stretched before her, she would look at the mask. It reminded her of her carefree, youthful days and of Manush’s love. Invariably, the burdens fell away. Her heart felt light and filled with hope; an assurance that there was bound to be light at the end of the dark tunnel.

Nevertheless, her Ma Kali extorted a price for Jharna’s upward spiral. There is always a price, isn’t it? For Jharna, it was her son’s waywardness. While Shampa and Rajat were in school, she had ensured they attended it regularly. She would rush back to serve them hot lunch. But at noon, she had to go back to her jobs. She would leave them with their books spread on the floor and strict injunctions to study. But how could she control them from afar? Every evening as she prepared their meal, she would say, ‘Study, study! Work on your books. The only study will take you places, nothing else. See, I am unlettered

and so I have to slog in other people’s kitchens. You mustn’t do this kind of work. You must get jobs in offices.’

‘Money, Ma. Only money takes you places,’ Rajat, now thirteen, would quip while Shampa would placidly peel potatoes. When annual results were announced, Rajat would have single-digit scores for all subjects and Shampa would just manage to scrape through. When Jharna had wept before their teachers, she was suggested coaching classes. It was another expense but Jharna added the expenditure and enrolled both into coaching classes nearby. However, Rajat would play hookey every other day. Shampa obediently went but she was not so bright. Rajat, the clever one, refused to study. After years of berating, beating and even emotional blackmail, Jharna had to sadly accept that the future she had dreamt for her children would not happen. By the time Rajat was fourteen, he had given up the pretence of school. He began to collect bets for the local betting or matka syndicate. He was paid a percentage of his collections and proudly

brought his earnings home. Jharna had thrown the crumpled notes on the floor and screamed, ‘Get out of my sight! Take your sinful wages and get out.’

But later in the day, when she grumbled to one of the ladies she cooked for, the woman had rationalised, ‘Now Jharna, don’t be so hard on your son. It is his way of earning. He is not gambling himself, is he?’ When she thought of it that way, the reality became apparent. Still, Jharna worried that the police would harass Rajat but his matka boss had everything tied up so tightly that none of his collection boys were ever noticed by the police. However, Jharna never asked her son to contribute to the household expenses.

Shampa had also dropped out of school and joined her grandmother in cleaning homes. Jharna did not touch her earnings either. She advised the girl to save up for her marriage. Yet, when the wedding took place, there had been demand for dowry. Jharna had to mortgage her home with the local moneylender to raise it. Still, she was content that she had got her daughter married to an honest, hard-working man with a steady job. He looked after Shampa and she would never need to work now.

After Shampa had left for her husband’s home, Jharna was lonely. Rajat came home late night if at all. It was then that the idea of growing a garden occurred to her. Like people keep fish, birds or dogs, Jharna kept plants. They were her pets. She sowed them, hoed them, watered them, nurtured them and sometimes even spoke to them as if they were her companions. She fed them peels and rinds of vegetables or fruits as also tea leaves from her kitchen as fertilizers. And to her delight, they bloomed.

Rajat came home when he craved his mother’s cooking. He would walk in declaring, ‘Ma, I am hungry. Look here is a tender chicken I got from the bazaar. Cook me a hot curry.’ Even if it was midnight and she had gone to bed, Jharna would shake off her drowsiness. Immediately switching on the gas, she would prepare the spices and soon a steaming meal would be ready.

There were some rare occasions when he would demand, ‘Ma, give me a hundred bucks, will you?’ Most of the time, she would give him the money.

Though there were times when Jharna would sneer, ‘What’s happened to your matka boss? Isn’t he paying you?’

Rajat wouldn’t be offended. He would laugh and say, ‘Yes, Ma. He paid me but I put some on bets today for a lark and lost. Just need some pocket money. I will return it to you next payday.’

Jharna would wrinkle up her nose. ‘Now you have started gambling too.’

‘It is another way to earn, Ma. Any way to earn money is good. The end is important not

the means to reach it, Ma.’

Jharna became curious. ‘Earn? Matka is gambling. How does one earn money by playing matka?’

And Rajat had sat down to explain to her the mysteries of placing bets on numbers and how one could double triple or quintuple one’s money. On his phone handset, he showed her number sheets. Jharna was fascinated. One night, she dreamt of rows of black numbers. In the long lines, certain numbers were encircled with red. Just on a hunch, next morning, she asked her son to place a bet of ten rupees on one of the numbers she had seen circled in her dream. Rajat had smiled at her and called up his boss. That evening, he gave Jharna thirty crisp rupees.

Puzzled, she asked, ‘What is this?’

‘You earned it from your ten rupee bet. Ma, your number won today.’ A slow smile had broken over Jharna’s face as Rajat held both his mother’s hands and danced around the room.

Jharna was intrigued, is it possible? She attempted to test her hypothesis. The next time she dreamt of a number or it popped up several times in her mind, she placed a bet on it. And lo behold, she won! It encouraged her. Repeatedly she relied on her intuition, gave Rajat a bit of money and won bets; small sums, of course. Most times, her bet would double or triple. She defended her itch by saying, ‘It’s only a game. I am just checking out my hunches. I am not gambling.’ Rajat would give her a knowing smile. But her winnings did bring in a steady stream of extra income. Soon, she had brought herself a simple mobile phone.

Ladies of the apartments would enter kitchens now to find her checking out number sheets on her phone between vigorous turns of the ladle or calling out numbers to Rajat over the sizzle of onion fritters. One of them remarked to her neighbour, ‘Can you believe it, my chef plays matka while cooking?’ Jharna overheard and smiled. She focused on dishing up more delicious piled-up platters for the lady. Soon, her employers got used to her games. They were amused by her latest fad and never believed Jharna

actually gambled.

But all thoughts of her harmless pleasures had faded as she chewed on Rajat’s strange behavior of last night. The korma sizzled in the wok, but Jharna was far away. Till last night, he had never demanded money of her or threatened her in this manner. What could be making him so aggressive? Had he lost his job? She wondered. Absentminded, she went to the door to dump the vegetable peels. About to sprinkle them on the dark mud of the flower pots, she paused. The erstwhile clean, well-swept front yard was

filthy. All kinds of rubbish and rotting stuff were strewn all over it. It had not been there when she had been sitting on the door step. So it had happened in the few minutes between then and her going in to cook. Jharna looked around and beyond the yard. Who could have done this? In the noonday heat, the empty, dusty road hugging the left corner of her house snaked away. Nobody lived in the tenement above hers. Suddenly, she heard a sound to her right and turned. The door to her only neighbour’s home was stealthily being pulled close from inside. So somebody was watching me unobserved. Was this misbehaviour theirs? Next door lived a family from Rajasthan. They had bought the tenement just a few years ago.

Jharna got a broom and carefully re-swept the ground piling the rubbish in a corner. She hated dealing with dirt after a bath. Tying a polybag around her hand and wrapping the end of her sari around her nose, she scooped the garbage up. Walking some distance up the road, she dumped it in the colony dustbin. Before entering her own home, she glanced once again at the closed door on her right before shutting her own front door.

Even as she returned to her kitchen, this incident went clean out of her head. Her thoughts revolved around her son’s unusual demands as she ruminatively chewed on her lunch. Why did he want so much money? Had his matka boss thrown him out? Was he in some kind of trouble? She decided to cautiously probe him when he came. She was carefully storing the korma and rice in the fridge hoping Rajat would come for lunch, when a knock came at the door. Jharna wiped her hands and opened it.

Moti, Rajat’s friend and co-worker at matka boss, stood on the step. Jharna gave a slight smile. ‘Moti? Come in. Come in. Do you want some lunch?’ He loved her cooking.

‘No, Aunty. Not today. Have you seen Rajat? Is he here?’

Jharna shook her head. ‘He left at dawn and hasn’t returned. Didn’t he go to work?’ ‘No Aunty. Boss is looking for him. He wants Rajat to collect from Manoj Seth. You know he is our biggest player. Boss only trusts Rajat to get his betting money.’ Moti turned away, muttering, ‘I don’t where Rajat goes to these days. I have to keep running after him.’

Jharna frowned at his retreating back. So Rajat had not lost his job. In fact, his boss was looking for him. Then why….? She stepped inside and was about to shut the door when her eyes fell on the door to the right. It was open. As she looked, a man came out. He wore a grey safari suit whose buttons strained across a bulging stomach. He turned to bid farewell to someone inside, so Jharna saw his face clearly. She did not know him. Or did she…? Something about him seemed familiar but she could not remember where, when or if she had seen him.

That night, Rajat came in but his usual loud jollity was missing. He was sulking. Jharna quietly served him dinner: soft, hot chapattis, the afternoon’s korma, and egg curry. He didn’t say a word as he ate. Afterward, he lit a bidi, a habit Jharna deplored. Tonight she bit back her usual admonishment. She approached him, sitting on the doorstep, blowing smoke into the cool night. Leaning against the doorjamb, she asked softly, ‘What is the matter, son? Is there some trouble? Do you want to tell me about it?’

He did not reply. Smoke rings hung in the air.

How different he is from his father, Jharna thought. His father had been a gentle soul and kind words never failed to move him.

Jharna waited for him to say something…anything. When he did not even acknowledge her presence, she turned back to clean up the kitchen. She felt deeply troubled. Rajat may have some rough edges, like the rest of the city youth but he deferred to her, his mother. His uncaring, callous silence worried her. On her knees, she swabbed the floor and tried to puzzle out reasons for his truculence. Suddenly, her wet mop touched his bare feet. He had come on silent feet to get a drink of water. He drew a bottle from the

fridge and poured out a glass as his mother crouched on the floor looking up at him. He drank it off in one draught and then met her eyes. For a long moment, mother and son looked at each other. Then he growled, ‘Don’t ask for reasons. Just get me ten lakhs, do you hear?’ Turning on his heel, he went out into the dark night.

Sleep eluded Jharna that night, too. Usually, she was bone tired by nightfall and was asleep the moment her head hit the pillow. Tonight, her head ached circling futilely around the mystery of her son’s weird sullen harshness. Her thoughts chased through the gloominess of her mind without a spark of comprehension. After a long frustrating night, she fell into fitful repose that conjured up a baffling dream. She dreamt that she was in a thick dark forest and she didn’t know her way. As she desperately looked for a path out of it, a light descended through the trees. Wonderingly, she approached it and saw Ma Kali in all her resplendent dark glory in the centre of the halo. Dumbstruck, Jharna could hardly believe her eyes when the deity spoke, ‘Go, my daughter, go forth. Find the seed and it will unravel. Only you can reach its end.’ And the Goddess disappeared. When Jharna turned herself around, Ma Kali was just behind her.

Wherever she looked, Jharna found the deity. Following the incandescent light that glowed around Kali, she came out of the forest into a meadow. Just then, Jharna’s eyes opened. The alarm was ringing at its usual 4 am setting, but her eyelids were scratchy as if there was sand behind them.

Jharna dragged herself through her morning chores. It won’t do to be absent from her kitchen duties that day. After a bath in the outhouse next to the front yard, Jharna came indoors. She closed the front door to complete dressing and her daily worship, when she heard a soft plop behind her. Jharna turned. It had come from outside the closed door! It sounded like a water balloon had hit it. Cautiously, she opened a slit in the doors. A foul stench hit her. She gagged. It smelt like cow dung, but how…? She opened the door some more. Sitting plumb in the centre of her just-swept doorstep was a polybag full of

fresh cow dung. Her eyes instantly glanced at the door to the right but it was tightly shut, its surface blandly innocent. Jharna sighed. Tucking up the gown she had worn for transit from the outhouse to the room, she stepped out. Holding her breath, she picked the terrible polybag up and swung it into the colony bin. Fortunately, it had not burst hitting the door and spattered its disgusting contents all over.

I have to get to the bottom of this. Let me be back from my jobs and then I will see, she deliberated hurrying with her toilet. I am already late.

All the way to her first post of duty, Jharna trotted as fast as she could but her mind was ticking even faster. Why were Malini and her family acting this way? Because she was sure that it was her next-door neighbour, Malini who was responsible for all the filth flung at her home.

Malini was the wife of a wall painter from Rajasthan. Ever since, they had moved in next door, most nights Jharna had woken up to angry shouts and loud screams. Clearly, her husband beat up Malini during drunken spates. Next morning, Malini would appear with welts on her arms or face. She had two boys; one went to school and the other was too young. In the evenings, Malini would sometimes saunter over to Jharna’s doorstep. She would either unabashedly express envy of the clean, green courtyard or complain about her husband’s misdemeanors or boast of her father’s wealth in faraway Alwar. Jharna had no interest in any of it but tolerated her because she felt sorry for the pale, thin, bruised woman. But as she tried to fathom out their present peculiar behavior, she realized that lately, Malini had not being coming over. What is the matter? First Rajat’s weirdness and now Malini’s? What is happening? Jharna reached her first job and then there was no mental space to think about anything until the afternoon as she rushed from one kitchen to another.

Jharna hardly noticed the blazing sunlight hurrying back home. She was determined to confront Malini. She knocked on the closed door scanning her own front yard. It looked as clean as she had left it. Malini opened the door, the baby on her hip.

‘Hanhhh?’ she intoned.

Jharna took the bull by the horns. ‘Why are you throwing rubbish into my front yard?’

‘Who? Me?’ Malini opened her eyes wide.

‘Yes, you,’ Jharna was not taken in one bit.

‘No, didi. I haven’t done anything. Must be the children.’

‘Whoever. Next time, it happens I will throw it right back at your door. So be careful.’ Jharna wagged a finger at the woman and stomped off to her own house. Malini banged the door shut to show her ire.

That evening, Rajat did not come home for dinner which itself was not unusual but given the present circumstances, it left Jharna anxious. At night, she tossed and turned until sheer weariness took its toll and sleep overcame her. Goddess Kali returned to her dreams. But tonight the deity was complaining. ‘Jharna, my child, how can I come to your home? The path leading up to it is full of garbage. I cannot walk on polluted ground. Clean it up, Jharna. Clean it, please.’

The dream and her plea seemed so very real, that Jharna woke up. Without being conscious of what she was doing, she got up and went to the worship alcove. She sat before the picture of the Goddess, her palms joined in prayer and whispered, ‘Show me the way, Ma.’ She remained sitting there for so long that she nodded off, curled up on the floor. When she woke the next day, she was still on the alcove floor. Her body ached from the hard floor while birds had cheeped outdoors.

Jharna jumped up. Oh no! I’m late…very late. She rushed around finishing chores whatever she could and left the rest for the afternoon. Taking a quick bath, she laid a fresh hibiscus flower before the Goddess and went out. As she ran down the narrow path connecting her front yard with the dusty road, she stopped short. In the middle of the way, the ground had been dug up. The hole was heaped with a lot of rubbish. Cushioned in its centre lay a head…its dead eyes glittering at her. With a cry, she stepped back.

Then holding her sari pallav to her nose, she went closer. It was the head of a pig…a piglet, to be accurate, cut off at the neck. Congealed blood spattered the dry leaves and other litter. On a reflex, her dream came back to her; Kali grumbling that the path to her home was filthy…polluted and she couldn’t visit her. The path to her home was actually filthy! Somebody had taken a lot of effort to pollute it with a carcass. None of it was here last evening.

Oh God! Why were people doing this to me?

That is for you to find out. In a flash came the immediate response to her mind.

Gingerly, Jharna stepped around the grotesque refuse. She felt numb. No reasoning occurred to her of this weird happening. One thing she was sure of was this was not a simple case of careless children. Somebody was deliberately dumping filth in her vicinity. There was a purpose to all this. But what purpose? And who? Malini? Her husband? Why? It always came back to the why. Questions went round and round in her head till she felt dizzy. But right now the focus was to get through the workday. She will

start looking for answers once she was back. She rushed down the road to the first apartment.

Returning home at noon, she met her mother on the way carrying heavy bags of groceries. Seeing Jharna, she said, “Oh good to catch up with you, dear. These bags are so heavy. Thought I would take a break, rest at your home and then lug them home.’

‘Of course, Ma. Let’s have lunch together too,’ Jharna said but her tone was flat.

Her mother frowned. Her daughter wasn’t usually so aloof. ‘Are you alright?’

‘Unhh…’ came the reply.

Her mother latched on like a crab. ‘What is the matter?’ she demanded.

‘I will tell you when we are indoors,’ Jharna said looking around suspiciously. Now the women were treading the path to Jharna’s front yard. Jharna was on the lookout for the litter heap but it had mysteriously vanished. Jharna stopped at the exact spot and scrutinized the area. Loose earth and small stones marked it. It seemed somebody had tried to cover the dug-out hole. Still, a rotten odour faintly wafted around it.

‘This was the place,’ Jharna muttered.

Her mother looked down, ‘Place? For what?’

Not replying, Jharna hustled her mother to her own front door. As she unlocked it, she took a quick glance at Malini’s door. It was shut.

Jharna silently served lunch. Both women sat comfortably on the scrubbed floor to polish off a meal of rice and delicious butterfish in mustard curry. First, they appeased their hunger bred by hard physical work. Then her mother sighed, ‘Jharna, you were born with a ladle in your hand. Ahhh…that fish is delicious.’A few more mouthfuls and her mother sat back. Giving her silent daughter a thoughtful look, she said, ‘Tell me everything, Jharna.’

Jharna looked up at her mother. Tears had welled up in her eyes. She began to give the complete litany of incidents of how Malini and her family were bent on messing the area around her tenement. Her mother listened without interruption and then said in a quiet voice, ‘It’s tantra.’

‘What?’ Jharna was flummoxed. ‘Tantra? Ritualistic magic? But why?’

‘That is what we need to find out,’ her mother said, licking the rice off her fingers. Both chewed slowly considering reasons. Her mother inquired, ‘Have you had a fight or an argument with these neighbours of yours?’

Jharna knit her brows trying to remember. ‘Noooo… I can’t remember a fight. The last time Malini came to my house, what did we talk about? Hmmm… it was a couple of months ago…’ Jharna tried to recall their conversation and then shook her head.

‘Nothing much other than some crazy idea of selling my room to them…’ Her voice trailed off.

‘Oh? And what did you say?’ Her mother asked.

‘No, of course not…I will never sell this room.’ Jharna was emphatic. ‘And I remember, she wouldn’t take a no…kept pestering me saying they would pay what? Fifteen lakhs or something. When I kept refusing, she got angry and it annoyed me too. Finally, she left in a huff.’ As Jharna related it all, a kind of understanding flashed. It must have reflected on her face because her mother nodded, ‘Exactly…’

‘But throwing filth at me won’t make me sell the room to them,’ Jharna slowly explored the logic of it.

‘Oh no, Jharna, not any filth; the bleeding head of a pig is not any filth. All this litter covers up some kind of amulet or object enclosing evil spells. That is how tantriks cast the evil eye. When magic spells are kept close to the victim, they exert power over the human soul. The power connects the soul to the tantrik who can then control the person. The tantrik can make the person ill, crazy… do anything.’

Jharna stared at her mother, the words quivering between them. Spell? Power over the

soul? Make him do anything? Finally, she croaked, ‘Rajat…’

‘What Rajat?’ Her mother pounced on Jharna. Rajat was her favourite grandchild. Describing the recent incidents in a frightened voice, out tumbled the tales of his erratic behaviour and his strident demands.

‘Isn’t it strange that the only way Rajat suggested you get the money was by selling this room?’ Her mother mused. The two women looked at each other as wheels whirred in each one’s head and stopped at the same conclusion.

Jharna tried recalling everything she knew about her neighbours. From the recesses of her mind crept out forgotten bits of revelations by Malini about her village priest who knew special rites and mantras. He could make the cattle fall sick or cure diseases that ordinary medicines could not. People consulted him when they wanted to harm people or protect themselves from harm. And just a few weeks ago, they had returned from a trip home.

Jharna spit it out. ‘That’s it. I’ve got the whole story. They want to buy my home and I won’t sell. So to push me, they are using a tantrik to sway my Rajat’s mind so that he throws tantrums for huge sums of money. To appease him, they expect that I will be forced to sell this room. But Ma, what foxes me is where have they got all the money that they are offering to pay me?

‘I know where,’ her mother who knew everything, nodded. ‘From that slimy builder who has been making rounds of our colony. He is going from house to house to persuade or coerce owners to sell their homes. Apparently, he wants to build a housing complex here. Everyone throws him out.’ Then it clicked! Jharna remembered the fat man in the safari suit on Malini’s doorway two days ago. He had seemed familiar and now she knew why. She had seen him in her father’s house spinning his sales spiels. Her father had

unceremoniously shown him the door. ‘He is providing them with money; to buy your room and a bribe to make you agree,’ her mother went on.

‘Why did they have to target my son? It is me that they have a problem with,’ wailed Jharna. Her heart ached thinking about the agony Rajat must be enduring as the tantrik’s puppet.

‘Because Ma Kali lives in your home,’ her mother declared, joining her palms in obeisance to the deity. She firmly believed that the goddess actually resided in Jharna’s home. Apparently, her mother had seen her flitting through the room sometimes. Instantly the pulsating dreams, so palpably real came back to Jharna. But she did not divulge them to her mother. For all her dedication to the goddess, Jharna did not

pander to superstitions. But tantra was different. She had seen its power; both good and evil back in the village. It could revive or kill.

Lunch over, her mother got to her feet with a grunt. She put a hand on Jharna’s head and said, ‘Don’t worry, daughter. We will get to the bottom of this. Nobody can harm my Rajat and get away with it. Let me talk to your father and we will think of a solution.’ Consoling Jharna, she took herself and her bags home. Jharna had no duties that evening as the families she worked for were out for the day. So, once her mother left, Jharna lay on her bed with ample time to ruminate over the problem. What should I do?

How should I fight these malignant forces that were working against me? Now that the whole sinister plot was revealed, she was suddenly conscious of baleful malice in the very air surrounding her.

Hardly had the sunset when there was a tremendous banging on her door. Hurriedly Jharna opened it. Rajat stumbled in. He was drunk; bellicose drunk. Jharna stared at him aghast and miserable as he began to weave around the room throwing down utensils, flinging things from the cupboards, wrecking the room. All the while, he was shouting, ‘Where is the money? Where have you hidden it? You are a witch. Give me the money, you harpy.’

Now that Jharna was aware of what was ailing him, she ran after him crying, ‘Rajat, lie down. You will hurt yourself, son. Please.’ But, he was deaf to her pleas. Mother and son ran around the room as it started resembling a place that a tornado had torn apart. Forcibly, Jharna tried to restrain Rajat but he hit out at her so hard that she was thrown to the ground. Her forehead began to bleed, cut open by the corner of the cupboard. She sat on the ground watching her son in the throes of a weird affliction and did not know

how to help him. Helpless tears of anguish fell as she beat her forehead in distress. She could not bear the torment of her son’s suffering. Eventually, tired out by his own exertions, he collapsed on the bed. Spread-eagled across it, the room gradually resounded with his drunken snores.

Jharna crawled into Kali’s alcove. Kneeling she placed her head on the floor. The congealed blood from her cut reddened it as she broke into a storm of inconsolable weeping. She howled like an animal in pain. The dark goddess, her hair floating like grey veil behind her, garlanded by bleeding heads, her gaudy tongue dropping to her chin gazed serenely at the grieving figure. A blood-red hibiscus sparkled like a ruby in the soft glow of the evening lamp burning at her feet.

Time ticked by but time has no meaning for lost souls. It took forever for Jharna’s sobs to subside. In her despondent desperation, she sought answers from her deity. What should I do, Ma? Show me. Help me. Save my son, Ma. Dazed with grief, she fell asleep on the floor.

It was after midnight when an electrical fault cut off all power in the colony. In Jharna’s room, the only light came from the earthen lamp steadily burning in Kali’s alcove. Her son’s chest rose and fell with heavy breaths but the noisy snoring had stopped. On the floor, the sleeping figure of the woman stirred. She raised her head and sat up. Slowly she came to her feet. Her movements were stiff-limbed like a wooden doll. It was as though she was unconscious of them. She went to directly to the Chaau mask on the wall

and took it down. It had not been shifted for years and clumps of dust from the wall behind fell on the floor but the woman ignored it. She brought it up to her face, adjusted the eye slits and tied the strings at the back of her head over the dark mass of hair that she had forgotten to plait the evening before.

Opening the front door, Jharna stepped out. Her courtyard was washed with silver. It was a full moon night. The entire colony was drowned in darkness broken by random stretches of moonlight. No lights framed windows nor any lit up the streets. She stood still in the centre of the front yard. The face mask with its high jagged headdress cast a long shadow in the moonlight. Her head tilted to one side as if catching sounds floating over the ether. Then she took the introductory pose of Chaau; parted legs on bent knees, arms were at right angles to her shoulders and bent at elbows, hands in perfect mudra.

First, she hit one heel on the ground then the other one and whirled up in a leap. The beat of the dhols or drums, the music of the reed pipes or mohuri that guided the steps of the Chaau were ringing in her ears across time. To its strains, she swirled, pirouetted, jumped high and swayed. Posturing in the combative stances of the Chaau war dance, she was a magnificent warrior. She bounded from one end of the yard to the other completely absorbed in the rhythms of her motions. She was Kali. She annihilated evil.

She was Shakti. She bestowed life. Her feet left the ground. She vaulted, shouting out cries traditional to the vigorous dance.

The door to the right opened cautiously. Sleepily, figures first peeped out and then curiosity led them out. Wondering what it was about they watched this ritualistic display. Some of the other residents in the neighbourhood, unable to sleep in the hot, dark night were sitting outdoors to catch a breeze. They heard the commotion and strolled towards the front row of tenements to investigate. A dervish with skirts flying

shrieking incomprehensibly met their astonished gaze. They froze at the bizarre sight of the leaping and gesticulating dancer with a large grinning head, its shadow elongated massively by the deceptive silvery glow of the new moon. It emitted bloodcurdling yells that sent chills down their spine. ‘That is a devil in Jharna’s front yard,’ whispered those brave enough to find their voice.

The performance went on for nearly an hour. The devil took one high leap and suddenly vanished behind the tall plants that stood sentinel around the yard. The spectators pushed each other and stumbled on the rough path in their hurry to run back into their homes and banged their doors shut. They were afraid the creature was now coming after them. In the near vicinity, Malini and her husband were paralysed with fear. Their guilt made them fear a mightier force than their tantrik’s will now avenge itself on them. Like

the rest, they rushed indoors, locked doors and windows in a futile attempt to keep out the terrifying monster. A few hours later, power was restored to the neighbourhood. A few windows lighted up and streetlights came on. But nobody and least of all Malini and her husband had the courage to investigate the inexplicable spectacle. They were cowering in their beds, covers over their heads.

The dancer had not vanished. She had collapsed; in fatigue brought on by the passionate, unrestrained rendition of Goddess Kali’s war dance. She was crumpled on the ground in nearly a faint. In the east, the sky was lightening when Jharna’s eyes flickered open. The dust was itching inside her nose. She was curled up on one side of the yard, her sari damp with morning dew. Her head was cushioned on a tuft of grass

and the mask had saved her face from being ground into the dust. But it was also not letting her breathe properly. She put her hands behind her head and untied the cords. Why am I wearing it anyway? She looked around utterly confused. And how am I lying outside in the front yard? My hair is loose and covered in dust. What has happened? Did the tantrik’s spell drag me outdoors? My son…! This last thought made Jharna scramble up and run indoors. He was still sprawled across her bed.

Quickly, she freshened up and set water to heat for the tea. It was already too late for her to go to work. Besides, she was feeling extremely exhausted this morning. She didn’t know why. As she was stirring sugar in cups of hot tea, Rajat stirred and then cautiously sat up holding his head.

He opened his eyes a little. Squinting at her, he mumbled, ‘Is my head still on my neck, Ma?’

He sounded exactly like her cheery Rajat, not the roaring angry beast of the last few days. Jharna laughed in relief at his silly query. ‘Yes, my dear boy. If you drink all that country stuff, it will make you foolish.’

‘You are right, Ma. I don’t know what came over me. You know I don’t drink that rubbish,’ he said as he climbed down from the bed to sit on the floor with her. Taking a long draught of the steaming tea, he gave contented sigh. “Ahhh! My Ma’s tea will cure anything.’

Jharna ruffled his hair affectionately. Sipping from her own cup, she regarded him. Gone was his scowl, his frowns, and his rough tongue. Thank God! Though, how did he change so suddenly? Anyway, I don’t care how. I am just glad he has changed …back to normal again. Finishing her tea, she went to the Kali’s alcove. On the way, her eyes fell on the brilliantly painted Chaau mask on the wall and suddenly clouds in her mind dissipated. Jharna looked from the mask to Goddess Kali sitting complacently on her seat. Memories of the night spiraled up and she smiled. It is all Ma’s doing. She showed the way…gave me strength. From a distance, because she had not yet bathed, she thanked Ma for restoring her son to her.

She was washing the tea things and Rajat was relaxing on the bed, when a sudden crash made them look up. Somebody was screaming! They ran out. Another crash and more shouts! All of it was coming from Malini’s room next door. And it didn’t sound like their usual quarrels and beatings. These were screams of terror. Mother and son blinked at each other. As they looked up at the house, the window shutters above the front door flung open and a big chair came flying through. It landed hard on the ground and two of

its legs splintered. What was happening?

For a couple of minutes, it was quiet. Then Malini’s face appeared at the open window. It was chalk white. Something had frightened her terribly. She saw them staring up at her. They saw her gulping. Then she screeched, ‘What are you looking at? Mind your own business. Go home.’ Jharna put a hand on her son’s back. Both of turned towards their own door.

Peace reigned till afternoon while Jharna cleaned up and cooked a meal. Rajat took it easy nursing his hangover. But it didn’t prevent him from eating a big breakfast and lunch. By noon he had decided to go out. Jharna had finally given in to her fatigue and lay down on the bed. A series of loud bangs and thumps from the next door made her lift her head. About to get up, she lay down again. After all, the neighbours didn’t want her help. In fact, hardly had they been neighbourly; snaring her son in horrible spells. Let

them kill themselves, for all I care!

That evening her mother came to visit. Over cups of tea, her mother whispered, ‘Is it true?’

‘What, Ma?’

‘What people are saying…’

‘And what are they saying?’

‘That Ma Kali was seen in your yard last night. You know, during the time when there were no lights…when the power went off. Did you see her?’

‘No, of course not, Ma. Don’t believe people. They must have seen a shadow in the dark and imagined things. But something much better has happened.’

‘What?’ Her mother cosied up for some gossip.

‘Rajat is back to what he was… to normal…just like he used to be. The tantrik’s spell must have been broken,’ Jharna said gleefully.

‘See? I told you. It’s Ma Kali. She must have touched him and cured him. Tantrik’s spells don’t break so easily. There has to be divine intervention,’ her mother nodded her head wisely.

Both the women sat quietly holding the warm teacups of their laps contemplating this idea when something like thunder crashed next door. Jharna’s mother started and hot tea splashed all over her sari. She quickly shook out the cloth looking fearfully outside.

‘What was that?’ she finally asked.

‘I don’t know Ma,’ Jharna shook her head. ‘This tumult has started since this morning. Things are being thrown out of their doors and windows. But the family doesn’t want anyone to go to them.’

Her mother peeped out of the door. Sure enough, there pots and pans, furniture, pillows were strewn on the ground all around the next door house. As she narrowed her eyes and scrutinized the house, a howling started up from inside. It was a fearful sound. On the street beyond, passersby halted and were trying to ascertain the reasons for the clamour. But nobody was coming close. Probably had been told off by Malini or her husband, surmised Jharna.

Her mother shut the door of Jharna’s room firmly. She sat down on the kitchen floor. Jharna began to gather the dirty cups and saucers. Her mother wagged her finger, ‘I know what is happening. This is all Ma Kali’s doing. Jai Ma Kali. Bless us, Ma.’ Closing her eyes, she joined her palms together and lifted them to her forehead repeatedly.

‘What do you mean, Ma? What do you know?’ Jharna inquired.

‘The tantrik’s spell has bounced back.’

‘Bounced back? What is that?’ Jharna put everything down and turned to her mother, bemused.

‘Well, this is what I heard in our village. Sometimes a tantrik’s spell may fail due to reasons such as it was not strong enough or it wasn’t executed according to instructions or a more powerful magic defeated its influence. When that happens, the spell bounces back on its perpetrators. Then the devastation that the spell targeted towards its victim is unleashed on those who had tried to use it to destroy another,’ explained her mother.

‘So…you mean…I mean…,’ Jharna stammered as the import of her mother’s words became clearer.

‘Yes. I mean that whatever havoc they wanted to vent on you is now released into their home. The devils are dancing on their souls now. You wait and watch. It will make their life hell. They will have to do penance. Without repentance there will be no peace in their lives,’ her mother assured her.

‘Ma, I don’t care what happens to them. My Rajat is cured and we are fine. That is what matters,’ Jharna said fervently.

‘All thanks are due to Ma and her glory. Victory to her, forever,’ her mother sent another reverent gesture towards the alcove where a fresh red hibiscus glowed.

‘Yes. It is Ma’s protection. It’s her unwavering black magic. The blessed spells that only she wields,’ Jharna agreed, glancing at the Chaau mask gently swinging on the wall.

Her mother got up from the floor. ‘I have to go home now…to cook for your father. That man…so old…but at every meal, he wants fresh fish,’ she cribbed.

That night tranquility reigned among the tenements. There were no untoward incidents or weird occurrences.

Next morning, when Jharna emerged into the yard, she examined the door on the right and was stunned. It was wide open, the doors swinging on its hinges in the morning breeze. So were the window shutters. Clearly, the house was deserted. Some time, during the night, Malini’s family had fled.

Her mother had been right, as always. Black magic had won the day.

By

By

By

By